====================

A homily offered by the Rev. Dr. C. Eric Funston at the Blessing of the Civil Marriage of Christopher William White and Robert William Powell, May 15, 2016, to the people assembled at First Congregational Church, 91 South Main Street, Sunderland, MA.

(The lessons for the service were: the poem who are you, little i by e.e. cummings; an excerpt from The Velveteen Rabbit by Margery Williams; and a portion of the Beatitudes (Matthew 5:1–10, NRSV). These lessons are set out below after the sermon.)

====================

Why are we here? Well, for a wedding, of course. But, more specifically, you may be wondering why an old Episcopal priest from Ohio is here in an 18th Century Puritan meeting house trying to do 21st Century Anglo-Catholic ritual. The short answer is that Chris asked me to. Chris was my music director at St Paul’s Church in Medina, Ohio, when he was a student at Oberlin (which his mother reminded me yesterday was just a few weeks ago), and we’ve been friends ever since.

Why are we here? Well, for a wedding, of course. But, more specifically, you may be wondering why an old Episcopal priest from Ohio is here in an 18th Century Puritan meeting house trying to do 21st Century Anglo-Catholic ritual. The short answer is that Chris asked me to. Chris was my music director at St Paul’s Church in Medina, Ohio, when he was a student at Oberlin (which his mother reminded me yesterday was just a few weeks ago), and we’ve been friends ever since.

The long answer to why we are all here is that we love these two men, that we wish them well, that we want to support them in this endeavor called “marriage,” and that we are asking God to bless them today and throughout their life together which (we hope) will be for life.

We’ve been treated to some readings, not all from Scripture, which they have chosen and which speak to them and to us about this thing they are doing.

First, that delightful little poem by e.e. cummings, who are you little, i – a bit of verse which reminds us of the magic of childhood which we sometimes seem to lose as we age. Cummings reminds us that it is never lost, but that it does often get buried under the pressures of adult life, and as anyone who is married will tell us, there are few adult demands more pressing than those of marriage. Chris and Rob have each just promised “to love [the other], comfort him, honor and keep him, in sickness and in health,” and to be faithful to him for life. Those are heavy promises, heavy obligations; they can weigh us down and bury the “little, i”. Another poet, Mary Oliver, has an answer to that concern which I will share with you in a moment.

Then we heard that wonderful excerpt from everyone’s favorite childhood book, Margery Williams’ The Velveteen Rabbit in which the Skin Horse observes that love is what makes us real and that people with hard edges or sharp corners, or break easily, seldom become real, and in which we see the Rabbit become real as his hair is loved off, his tail becomes unsewn, and the pink is kissed off his nose.

Chris and Rob have paired these readings with the Beatitudes, Jesus’ list of people who are blessed not because of anything they do but because of who they are. This is not Jesus’ social program; he’s not laying out a course of conduct by which we can earn blessedness. It occurred to me as I went over these three readings that what Jesus is doing is describing people whose “little, i” has not been buried (or, if it was buried at one time, it has been dug up again); he describing those who either never had sharp edges, or whose sharp edges have been softened and worn away, whose hair has been loved off by others, who have been hugged by others so tightly that their joints are loose and shabby, whom people have kissed so often that the pink has rubbed off their noses. And he is here promising that the reward for being loved like that is blessedness, what the Skin Horse calls “reality.” That is what we hope for Rob and for Chris when we ask God to bless them in this thing, this relationship we call “marriage.”

Marriage in the eyes of the State is a contract; two people make mutual promises and if they fail live up to those promises, the law will take action. If one or both of them later decide they don’t want to honor the contract, they have to go to court to be relieved of its obligations. In the eyes of the church, however, marriage is much more – it is what we call a “sacrament.” A sacrament, we say, is “an outward and visible sign of an inward and spiritual grace.”

So what is the outward and visible sign of marriage? When I ask that question in confirmation classes, the most common answer is “the rings.” Good answer, but not exactly right.

I’m wearing stole which has on it three symbols connected with marriage. The interlocked rings, a funny looking thing that looks like a capitol-P with a crossbar, and palm branch. Although the rings are not the outward and visible sign, on this stole they represent that sign, which is the couple themselves. The sacramental sign of marriage is the two people who live together in the sacramental relationship; they symbolize the grace of human companionship, the possibility of love and peace between individuals so deep and so profound that they (in Jesus’ words) “become one flesh.” They are living symbols of the hope and possibility that all humanity can do that as a world-wide community. In the Skin Horse’s word, they make it real.

But they do not do that as a couple alone, they do that with through the grace and empowerment of God; thus, the second symbol, which isn’t a P-with-a-crossbar. This symbol is a stylized combination of the Greek letter Chi and Rho, the first two letters of the word “Christ”. It reminds us that God a part of, a party to, and a partner in every marriage. In token of that reality, Chris and Rob will share the sacrament of the Eucharist today, another sacrament reminding us of Jesus’ words “Remember, I am with you to the end of the ages.”

The third emblem on my stole is a palm branch. Some of you will remember the story of Jesus’ triumphal entry into Jerusalem which the church celebrates every year on the day called “Palm Sunday.” The people along his path from the Mount of Olives, through the Kidron Valley, and into the Holy City spread his path with branches of palm and waved branches as they sang “Hosanna!” and wished him well. On this stole, this palm branch represents the crowds who support Chris and Rob; in other words, you and all the people you represent! A marriage does not exist in a vacuum; it is a social contract, a sacrament, a way of life lived out in the context of a community and the married couple rely upon that community. Each of these men will not be able to live up to that promise to love, comfort, honor, keep and be faithful to the other unless you help them do it. That’s why we began this service not just with their vows, but with yours. You were asked: “Will all of you witnessing these promises do all in your power to uphold these two persons in their marriage?” and you answered loudly and whole-heartedly, “We will!” They are going to rely on that promise . . . a lot!

So, I suggested that e.e. cummings’ concern about our buried “little, i” has been answered by another poet, Mary Oliver. I will close with her answer, the poem “I worried.”

I worried a lot. Will the garden grow, will the rivers

flow in the right direction, will the earth turn

as it was taught, and if not how shall

I correct it?Was I right, was I wrong, will I be forgiven,

can I do better?Will I ever be able to sing, even the sparrows

can do it and I am, well,

hopeless.Is my eyesight fading or am I just imagining it,

am I going to get rheumatism,

lockjaw, dementia?Finally I saw that worrying had come to nothing.

And gave it up. And took my old body

and went out into the morning,

and sang.

Chris . . . Rob . . . your “little, i” (like all of ours) is in constant danger of being buried under the concerns of life, none of which are heavier than the promises you have made to be responsible in love to and for one other special person. But you have not made those promises alone; you have the grace and support of God, and you have the love and support of this community of family and friends. So don’t let that heaviness bury you . . . just love one another through rheumatism and lockjaw and dementia and hair being rubbed off and the pink being kissed away; just get up every day and go out into the morning and sing.

The Readings:

who are you, little i by e.e. cummings

who are you, little i

(five or six years old)

peering from some highwindow; at the gold

of November sunset

(and feeling: that if day

has to become nightthis is a beautiful way)

From The Velveteen Rabbit by Margery Williams

“What is REAL?” asked the Rabbit one day, when they were lying side by side near the nursery fender, before Nana came to tidy the room. “Does it mean having things that buzz inside you and a stick-out handle?”

“Real isn’t how you are made,” said the Skin Horse. “It’s a thing that happens to you. When a child loves you for a long, long time, not just to play with, but REALLY loves you, then you become Real.”

“Does it hurt?” asked the Rabbit.

“Sometimes,” said the Skin Horse, for he was always truthful. “When you are Real you don’t mind being hurt.”

“Does it happen all at once, like being wound up,” he asked, “or bit by bit?”

“It doesn’t happen all at once,” said the Skin Horse. “You become. It takes a long time. That’s why it doesn’t happen often to people who break easily, or have sharp edges, or who have to be carefully kept. Generally, by the time you are Real, most of your hair has been loved off, and your eyes drop out and you get loose in the joints and very shabby. But these things don’t matter at all, because once you are Real you can’t be ugly, except to people who don’t understand.”

That night, and for many nights after, the Velveteen Rabbit slept in the Boy’s bed. At first he found it rather uncomfortable, for the Boy hugged him very tight, and sometimes he rolled over on him, and sometimes he pushed him so far under the pillow that the Rabbit could scarcely breathe… But very soon he grew to like it, for the Boy used to talk to him, and made nice tunnels for him under the bedclothes that he said were like the burrows the real rabbits lived in. And they had splendid games together, in whispers… And when the Boy dropped off to sleep, the Rabbit would snuggle down close under his little warm chin and dream, with the Boy’s hands clasped close round him all night long.

And so time went on, and the little Rabbit was very happy-so happy that he never noticed how his beautiful velveteen fur was getting shabbier and shabbier, and his tail becoming unsewn, and all the pink rubbed off his nose where the Boy had kissed him.

And one night Nana grumbled as she cleaned the rabbit off with a corner of her apron. “You must have your old Bunny!” she said. “Fancy all that fuss!”

The Boy sat up in bed and stretched out his hands. “Give me my Bunny!” he said. “You mustn’t say that…. He’s REAL!

The Beatitudes (Matthew 5:1-10, NRSV)

1 When Jesus saw the crowds, he went up the mountain; and after he sat down, his disciples came to him.

2 Then he began to speak, and taught them, saying:

3 “Blessed are the poor in spirit, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven.

4 “Blessed are those who mourn, for they will be comforted.

5 “Blessed are the meek, for they will inherit the earth.

6 “Blessed are those who hunger and thirst for righteousness, for they will be filled.

7 “Blessed are the merciful, for they will receive mercy.

8 “Blessed are the pure in heart, for they will see God.

9 “Blessed are the peacemakers, for they will be called children of God.

10 “Blessed are those who are persecuted for righteousness’ sake, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven.”

====================

A request to my readers: I’m trying to build the readership of this blog and I’d very much appreciate your help in doing so. If you find something here that is of value, please share it with others. If you are on Facebook, “like” the posts on your page so others can see them. If you are following me on Twitter, please “retweet” the notices of these meditations. If you have a blog of your own, please include mine in your links (a favor I will gladly reciprocate). Many thanks!

====================

Father Funston is the rector of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Medina, Ohio.

Dr. Robert Waldinger is the current director of the Harvard Study of Adult Development which is something called “a longitudinal cohort study” in which the same individuals are observed over a long study period. It is the longest running study of this kind in history. For 75 years researchers have tracked the lives of 724 men from all walks of life.

Dr. Robert Waldinger is the current director of the Harvard Study of Adult Development which is something called “a longitudinal cohort study” in which the same individuals are observed over a long study period. It is the longest running study of this kind in history. For 75 years researchers have tracked the lives of 724 men from all walks of life.

There’s a lady who’s sure

There’s a lady who’s sure In Jerusalem, just outside the walled Old City to the south is a church built on the place where the house of Caiaphas, the high priest who oversaw Jesus’ crucifixion, is believed to have been. The church is named St. Peter in Gallicantu; the name is from the Latin meaning, “St. Peter where the rooster crowed.” It is a reference, of course, to Peter’s three denials of Christ in the courtyard of the high priest’s house.

In Jerusalem, just outside the walled Old City to the south is a church built on the place where the house of Caiaphas, the high priest who oversaw Jesus’ crucifixion, is believed to have been. The church is named St. Peter in Gallicantu; the name is from the Latin meaning, “St. Peter where the rooster crowed.” It is a reference, of course, to Peter’s three denials of Christ in the courtyard of the high priest’s house.  Every year on the Second Sunday of the Easter season, we read the story from John’s Gospel of Thomas’s refusal to accept the testimony of his fellow disciples, but in each year of the Lectionary Cycle, it is coupled with different lessons from the Book of Acts and a different epistle lesson. So this year, in Year C of the cycle, we have heard of the confrontation between Peter and the high priest about the apostles’ teaching in the Temple, and we have heard part of the introduction of John of Patmos’ Revelation.

Every year on the Second Sunday of the Easter season, we read the story from John’s Gospel of Thomas’s refusal to accept the testimony of his fellow disciples, but in each year of the Lectionary Cycle, it is coupled with different lessons from the Book of Acts and a different epistle lesson. So this year, in Year C of the cycle, we have heard of the confrontation between Peter and the high priest about the apostles’ teaching in the Temple, and we have heard part of the introduction of John of Patmos’ Revelation.  Litigation attorneys and fishermen have something in common… We like to tell stories. Fishermen tell about “the one that got away.” Trial lawyers prefer to tell about the ones we got!

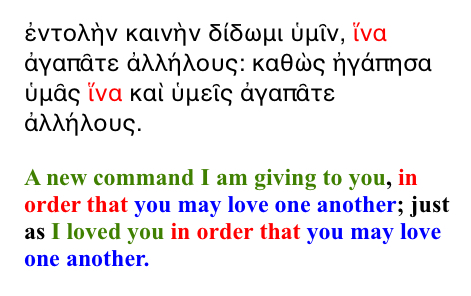

Litigation attorneys and fishermen have something in common… We like to tell stories. Fishermen tell about “the one that got away.” Trial lawyers prefer to tell about the ones we got! They have had their dinner during which, predicting his death, Jesus has instructed them to share bread and wine again and again in his memory. Jesus has washed their feet. He has given them his New Commandment, “Love one another.” Now, dinner ended, it is time for a stroll in the garden.

They have had their dinner during which, predicting his death, Jesus has instructed them to share bread and wine again and again in his memory. Jesus has washed their feet. He has given them his New Commandment, “Love one another.” Now, dinner ended, it is time for a stroll in the garden. It’s April! When did that happen?

It’s April! When did that happen? What is Jesus up to? Why is he doing this?

What is Jesus up to? Why is he doing this?