Again this week as last, our first reading today is from the First Book of Kings and like last week’s, it is a prayer spoken by King Solomon. Last week, it was a private prayer spoken in a dream late at night. Today, it is a public prayer. As long as it was, this reading is just a small part of the dedicatory prayer that Solomon offered when the Temple was finished and consecrated. In it, Solomon asks an important question, “[W]ill God indeed dwell on the earth?”[1] More specifically, Solomon is asking if God will dwell in the Temple, and the wise king immediately answers his own question: “[H]eaven and the highest heaven cannot contain you, much less this house that I have built!”[2]

Again this week as last, our first reading today is from the First Book of Kings and like last week’s, it is a prayer spoken by King Solomon. Last week, it was a private prayer spoken in a dream late at night. Today, it is a public prayer. As long as it was, this reading is just a small part of the dedicatory prayer that Solomon offered when the Temple was finished and consecrated. In it, Solomon asks an important question, “[W]ill God indeed dwell on the earth?”[1] More specifically, Solomon is asking if God will dwell in the Temple, and the wise king immediately answers his own question: “[H]eaven and the highest heaven cannot contain you, much less this house that I have built!”[2]

The building of the Temple in 957 BCE[3] marked a very significant change in the Jewish religion. Well, really, let’s not call it the Jewish religion because it wasn’t that, yet. Let’s just say, “The religion of the people of Israel.” These people were not, though we often imagine them to be, strict monotheists. Even in this prayer, Solomon leaves open the question of whether there might be gods other than their God: “O Lord, God of Israel, there is no God like you in heaven above or on earth beneath.”[4] There might be other gods, lesser gods perhaps, demigods, or even demons, part of a heavenly pantheon of gods, but this God, the God of the People of Israel is greater than any of those others.

At this time, the ancient Semitic peoples of the Near East were what sociologists call “henotheists.” Each nation, sometimes even each clan or family, had its own belief system, its own religion, its own god, which it believed to be supreme over the gods of their neighbors. And nearly all of these religions believed their gods to be sort of tied to the land. If you moved from one place to another, you stopped worshiping the god of the first place and took up the worship of the god of your new residence. If a woman married outside of her family or tribe, married into a different clan, she would give up the religion of her family and take up that of her husband.

The People of Israel’s God, however, was different. Their God was not tied to a particular place. Their God was connected to a holy object, instead. God was associated with the Ark of the Covenant which they had created in the desert to contain God’s holy relics, the tablets of the Law given to Moses at Sinai (together with a pot of manna and Aaron’s staff). They carried the Ark with them, actually before them, as they traveled through the desert, as they crossed into the Holy Land, as they conquered the Canaanites and took possession of the country.

Initially, the Ark and its tent, called “the Tabernacle,” was set up at the Canaanite worship center in Shiloh.[5] It seems to have stayed there for about 300 years, until the Battle of Aphek, when the Philistines captured the Ark and took it away. On hearing about the capture, the priest Eli immediately died and his daughter-in-law, voicing the belief that God traveled with the Ark, exclaimed, “The glory has departed from Israel, for the ark of God has been captured.”[6] Capturing the Ark turned out not to have been a good idea for the Philistines; wherever they took it bad things happened. So, they sent it back to the Israelites who put in a place called Kiriath-Jearim where it stayed until King David brought it to Jerusalem.

We know that David wanted to build a permanent location for it; he wanted to build a Temple. But God refused. He told David, through the prophet Nathan,

Are you the one to build me a house to live in? I have not lived in a house since the day I brought up the people of Israel from Egypt to this day, but I have been moving about in a tent and a tabernacle.[7]

So David did not build the Temple, but he did build a a new Tabernacle in Jerusalem and brought the Ark there. We are told

David danced before the Lord with all his might;

David was girded with a linen ephod. So David and all the house of Israel brought up the ark of the Lord with shouting, and with the sound of the trumpet. . . . They brought in the ark of the Lord, and set it in its place, inside the tent that David had pitched for it.[8]

David was inspired to design the Temple, but he never built it.[9] His son Solomon was the one to do that.

So that is where we are this morning. The Temple has been finished, the sacred implements from David’s tent have been moved into it, the Ark of the Covenant has been installed into the Holy of Holies where only the High Priest is allowed to go, and Solomon offers this long prayer of dedication. In it he asks that very important question: “[W]ill God indeed dwell on the earth?” By building the Temple, Solomon sought to provide God a place to dwell on earth and, in so doing, he made the religion of his people more like that of their neighbors than it had been.

Remember those other religions had tied their gods to particular places whereas the God of Israel had moved about the countryside with his People. Now God had a permanent home, at least for a while. About 300 years later, in the latter half of the Seventh Century BCE, during what’s known as the Deuteronomic Reform, the Jews would centralize God’s worship in a the Temple, interpreting a decree in the Book of Deuteronomy to mean that the cultic part of their faith could only be performed in that place. Sure, people could gather anywhere for prayer, they could go synagogues for religious instruction, but they could only offer sacrifice and perform the cultic rituals in the Temple at Jerusalem. God had become tied to a place.

In the first years of the Sixth Century BCE, Babylonia conquered Jerusalem, took the Israelite leadership into captivity, and destroyed the Temple. The Ark disappeared and, to this day, no one knows where it is; the Ethiopian Orthodox Church claims to have it, but not many people believe that. During the Exile, the Jews refused to follow that earlier Semitic tradition in which you worshiped the god or gods of the place where you lived. Instead, they looked back to Jerusalem where the Temple had been, where God had become tied to a place. Psalm 137 reflects this:

By the waters of Babylon we sat down and wept,

when we remembered you, O Zion.

* *

If I forget you, O Jerusalem,

let my right hand forget its skill.

Let my tongue cleave to the roof of my mouth

if I do not remember you,

if I do not set Jerusalem above my highest joy.[10]

By the time of Jesus, Solomon’s question had been firmly answered for the Jews. Yes, said their religious leadership, God will dwell on earth, in this place, this Temple in Jerusalem. Even now, although Solomon’s Temple was destroyed and a second one built and destroyed, even though Jews live throughout the world and gather in many places to worship, they still look Jerusalem. The Wailing Wall, the western wall of the Temple Mount, the only part of the Temple complex to remain standing, is the holiest site in Judaism. God dwells in the Temple, even though it is in ruins.

In the birth of Jesus, however, God gave a different answer: God will not dwell in a building in a particular place. John’s Gospel begins with this affirmation, “The Word became flesh and lived among us.”[11] Will God indeed dwell on earth? Yes, God will live among God’s people as one of us. God lived among us as an infant who was born in Bethlehem and grew up to become a rabbi. God lived among us as an itinerant rabbi who had no home and was accused of being a rabble-rouser. God lived among us as a rabble-rouser condemned to die a criminal’s death. God lived among us as a criminal executed on a cross and risen to new life. God lives among us now.

On the night before he died, Jesus gathered with his friends for a Passover meal. There is some debate as to whether it was a Seder, the sacred meal of Judaism, but if it was he radically changed its nature, just as Solomon building the Temple eventually changed the nature of the religion of Israel. In the Passover meal, Jews become one with their ancestors; the Hebrews of the Passover story are brought present to them in the ritual of the Seder and they, in turn, live the Passover story through the meal, but the meal does not bring God into their midst. When Jesus took the bread of affliction and said, “This is my body,” when he took the cup of blessing and said, “This is my blood,” when he told his followers, “Do this when you remember me,” when he promised, “Where two or three gather, I am there,” Jesus gave us a power and an obligation unlike any given before to any people by God. We have the privilege to bring God present among us in the Bread and Wine of the Eucharist, the Christ’s Body and Blood. As one of our oldest Eucharistic Prayers says, in words which recall the promise of today’s gospel lesson, when we receive Holy Communion we are “filled with [God’s] grace and heavenly benediction, and made one body with [Christ], that he may dwell in us, and we in him.”[12]

Will God indeed dwell on earth? Yes, God will and God does dwell on earth. God dwells with the followers of Jesus when we gather and feed on his flesh and drink his blood, in word and sacrament, wherever that may be.

You all know, I’m sure, that on July 20, 1969, Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin landed on moon. I’m pretty sure that if you were alive back then, you remember exactly where you were on that day at that moment when Armstrong stepped out of the lunar lander and became the first human being to walk on another world. What almost nobody knew until a long time afterward was that something else happened on the moon that day. Buzz Aldrin, a devout Christian and an ordained elder in his Presbyterian congregation, had taken a communion kit with some bread and wine to the moon. In the Presbyterian Church, the lay elders of the church who serve a function similar to our vestry members, are actually ordained by their congregation, and that ordination empowers them to bless the elements of Holy Communion. At the time Aldrin and Armstrong landed on the moon, the pastor and members of his Presbyterian church were watching TV but unlike most of us, they were also celebrating communion. Armstrong joined them across space, blessing the bread and wine on the moon and partaking there of Holy Communion.[13]

In the act of Holy Communion, we are joined with Christians everywhere and everywhen — with all those in every place who also take part in the Eucharistic feast, with all those who have done so at every Eucharist since Christ’s last supper with his disciples, with all those who will celebrate Communion in the future. We are joined with them because God dwells in all of us whenever we eat of Christ’s Body and drink of Christ’s Blood, no matter where we are.

Will God indeed dwell on the earth? Yes! Will God dwell on the moon? Yes! God dwells with God’s People who feast on the Word Incarnate, and God will dwell with us across time and across space wherever we may go. Amen.

====================

This homily was offered by the Rev. Dr. C. Eric Funston on the Fourteenth Sunday after Pentecost, August 25, 2024, to the people of St. Thomas Episcopal Church, Berea, Ohio, where Fr. Funston was guest presider and preacher.

The lessons for the service were 1 Kings 8:[1, 6, 10-11],22-30,41-43; Psalm 84; Ephesians 6:10-20; and St. John 6:56-69. These lessons can be read at The Lectionary Page.

The illustration is a re-creation of Solomon’s Temple from Free Bible Images

====================

Notes:

Click on footnote numbers to link back to associated text.

[1] 1 Kings 8:27 (NRSV)

[2] Ibid.

[3] Temple of Jerusalem, Encyclopedia Britannica, updated August 18, 2024, accessed August 24, 2024

[4] 1 kings 8:23 (NRSV)

[5] Joshua 18:1

[6] 1 Samuel 4:22 (NRSV)

[7] 2 Samuel 7:5-6 (NRSV)

[8] 2 Samuel 6:15, 17 (NRSV)

[9] 1 Chronicles 28:11-19

[10] Psalm 137:1,56 (The Book of Common Prayer 1979, page 792)

[11] John 1:14 (NRSV)

[12] The Holy Eucharist, Rite 1, The Book of Common Prayer 1979, page 336

[13] Buzz Aldrin, When Buzz Aldrin Took Communion on the Moon, Guideposts, October 1970, accessed August 24, 2024

Our gospel reading this morning is taken from the Fourth Gospel, the Gospel according to John, which I’m sure you know is the sort of odd-man-out of the gospels. The other three gospels, the so-called Synoptic Gospels (a Greek word meaning that they see the Jesus story in the same way), pretty much agree and present the events of Jesus’ ministry in the same order over a one-year time-line. John tells the story in a completely different way, with a three-year time span and a different order of events.

Our gospel reading this morning is taken from the Fourth Gospel, the Gospel according to John, which I’m sure you know is the sort of odd-man-out of the gospels. The other three gospels, the so-called Synoptic Gospels (a Greek word meaning that they see the Jesus story in the same way), pretty much agree and present the events of Jesus’ ministry in the same order over a one-year time-line. John tells the story in a completely different way, with a three-year time span and a different order of events.  The United States is, at least ostensibly, a very religious country. Nearly two hundred years ago, Alexis de Tocqueville wrote that “there is no country in the world where … religion retains a greater influence over the souls of men than in America; and there can be no greater proof of its utility and its conformity to human nature than that its influence is powerfully felt over the most enlightened and free nation of the earth.”

The United States is, at least ostensibly, a very religious country. Nearly two hundred years ago, Alexis de Tocqueville wrote that “there is no country in the world where … religion retains a greater influence over the souls of men than in America; and there can be no greater proof of its utility and its conformity to human nature than that its influence is powerfully felt over the most enlightened and free nation of the earth.” There is a graphic artist named Brian Andreas whose work I can’t really describe to you. He uses a lot of primary colors, representational but non-realistic images, and words to create prints called “StoryPeople.” In one of them that I saw a while back is this quotation (I don’t know if it’s original to Mr. Andreas or quoted from someone else):

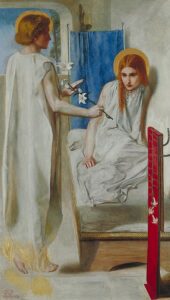

There is a graphic artist named Brian Andreas whose work I can’t really describe to you. He uses a lot of primary colors, representational but non-realistic images, and words to create prints called “StoryPeople.” In one of them that I saw a while back is this quotation (I don’t know if it’s original to Mr. Andreas or quoted from someone else): When I was about 8 or 9 years of age, my grandparents gave me an illustrated bible with several glossy, color illustrations of various stories. They weren’t great art, but they were clear and very expressive. My favorite amongst them was the illustration of today’s gospel lesson.

When I was about 8 or 9 years of age, my grandparents gave me an illustrated bible with several glossy, color illustrations of various stories. They weren’t great art, but they were clear and very expressive. My favorite amongst them was the illustration of today’s gospel lesson. What is Lent all about?

What is Lent all about? Here we are at the end of the first period of what the church calls “ordinary time” during this liturgical year, the season of Sundays after the Feast of the Epiphany during which we have heard many gospel stories which reveal or manifest (the meaning of epiphany) something about Jesus. On this Sunday, the Sunday before Lent starts on Ash Wednesday, we always hear some version of the story of Jesus’ Transfiguration, a story so important that it is told in the three Synoptic Gospels, alluded to in John’s Gospel, and mentioned in the Second Letter of Peter.

Here we are at the end of the first period of what the church calls “ordinary time” during this liturgical year, the season of Sundays after the Feast of the Epiphany during which we have heard many gospel stories which reveal or manifest (the meaning of epiphany) something about Jesus. On this Sunday, the Sunday before Lent starts on Ash Wednesday, we always hear some version of the story of Jesus’ Transfiguration, a story so important that it is told in the three Synoptic Gospels, alluded to in John’s Gospel, and mentioned in the Second Letter of Peter. In the Episcopal Church, when we baptize a person, we pray that God will “give them an inquiring and discerning heart, the courage to will, and to persevere, a spirit to know, and love, [God], and the gift of joy, and wonder in all [God’s] works.”

In the Episcopal Church, when we baptize a person, we pray that God will “give them an inquiring and discerning heart, the courage to will, and to persevere, a spirit to know, and love, [God], and the gift of joy, and wonder in all [God’s] works.” There’s a story about a pastor giving a children’s sermon. He decides to use a story about forest animals as his starting point, so he gathers the kids around him and begins by asking them a question. He says, “I’m going to describe someone to you and I want you to tell me who it is. This person prepares for winter by gathering nuts and hiding them in a safe place, like inside a hollow tree. Who might that be?” The kids all have a puzzled look on their faces and no one answers. So, the preacher continues, “Well, this person is kind of short. He has whiskers and a bushy tail, and he scampers along branches jumping from tree to tree.” More puzzled looks until, finally, Johnnie raises his hand. The preacher breathes a sigh of relief, and calls on Johnnie, who says, “I know the answer is supposed to be Jesus, but that sure sounds an awful lot like a squirrel to me.”

There’s a story about a pastor giving a children’s sermon. He decides to use a story about forest animals as his starting point, so he gathers the kids around him and begins by asking them a question. He says, “I’m going to describe someone to you and I want you to tell me who it is. This person prepares for winter by gathering nuts and hiding them in a safe place, like inside a hollow tree. Who might that be?” The kids all have a puzzled look on their faces and no one answers. So, the preacher continues, “Well, this person is kind of short. He has whiskers and a bushy tail, and he scampers along branches jumping from tree to tree.” More puzzled looks until, finally, Johnnie raises his hand. The preacher breathes a sigh of relief, and calls on Johnnie, who says, “I know the answer is supposed to be Jesus, but that sure sounds an awful lot like a squirrel to me.” When I find myself in times of trouble,

When I find myself in times of trouble,