When I find myself in times of trouble,

When I find myself in times of trouble,

Mother Mary comes to me

Speaking words of wisdom, let it be

And in my hour of darkness

she is standing right in front of me

Speaking words of wisdom, let it be[1]

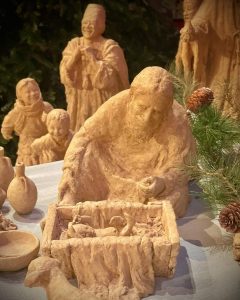

I did not begin this morning with “Happy Christmas” or “Merry Christmas” because, although it’s December 24th, it’s not Christmas; it’s not even Christmas Eve yet! The rest of the world may want you to think it’s Christmas and that it has been since mid-October, but the Episcopal Church insists that it is not yet Christmas. In fact, there’s still more than nine months until Christmas if we believe the good news we just heard from the evangelist Luke! We still have some time to wait for trees and carols and packages, for festive dinners and “chestnuts roasting on an open fire” and the “holy infant so tender and mild.” We still have some of the Advent season to complete and so on this, the Fourth Sunday of Advent, we focus our attention on Mary and consider not the end of her pregnancy, but its beginning, that moment when the Angel Gabriel told her that she had been chosen to be the mother of the Messiah.

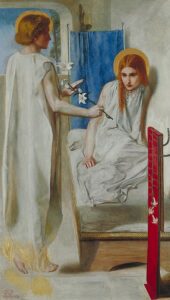

Visual artists depict the stories of the bible in many fascinating ways and their works can help us explore scripture’s meaning. Often their images capture or suggest nuances in a story that we might miss just hearing the words. This morning, I’d like to tell you about three paintings that particularly speak to me about the Annunciation. They are the Pre-Raphaelite Dante Gabriel Rosetti’s Ecce Ancilla Domini painted in the 1850s, Florentine painter Sandro Botticelli’s late 15th Century Cestello Annunciation, and a contemporary piece by American artist John Collier.

This is the second of three Sundays during which our lessons from the Gospel according to Matthew tell the story of an encounter between Jesus and the temple authorities. Jesus has come into Jerusalem, entered the Temple and had a somewhat violent confrontation with “the money changers and … those who sold doves,”

This is the second of three Sundays during which our lessons from the Gospel according to Matthew tell the story of an encounter between Jesus and the temple authorities. Jesus has come into Jerusalem, entered the Temple and had a somewhat violent confrontation with “the money changers and … those who sold doves,” When I was a sophomore in college, I lived in a dormitory suite with nine other guys: six bedrooms, two sitting rooms, and a large locker-room style bathroom. About mid-way through the first semester, one of our number, a 3rd-year biochemistry major, suggested that set up a small brewery in one of the sitting rooms. We all read up on how to make beer and thought it was a great idea; so we helped him do it. It takes three to four weeks to make a batch of beer, so over the next few months we made quite a bit of beer.

When I was a sophomore in college, I lived in a dormitory suite with nine other guys: six bedrooms, two sitting rooms, and a large locker-room style bathroom. About mid-way through the first semester, one of our number, a 3rd-year biochemistry major, suggested that set up a small brewery in one of the sitting rooms. We all read up on how to make beer and thought it was a great idea; so we helped him do it. It takes three to four weeks to make a batch of beer, so over the next few months we made quite a bit of beer.  We “boast in our sufferings,” writes Paul to the Romans, “knowing that suffering produces endurance, and endurance produces character, and character produces hope, and hope does not disappoint us….”

We “boast in our sufferings,” writes Paul to the Romans, “knowing that suffering produces endurance, and endurance produces character, and character produces hope, and hope does not disappoint us….” It’s the last Sunday of the Christian year, sort of a New Year’s Eve for the church. We call it “the Feast of Christ the King” and we celebrate it by remembering his enthronement. Each year on Christ the King Sunday we read some part of the crucifixion story. As Pope Francis reminded the faithful in his Palm Sunday homily a few years ago, “It is precisely here that his kingship shines forth in godly fashion: his royal throne is the wood of the Cross!”

It’s the last Sunday of the Christian year, sort of a New Year’s Eve for the church. We call it “the Feast of Christ the King” and we celebrate it by remembering his enthronement. Each year on Christ the King Sunday we read some part of the crucifixion story. As Pope Francis reminded the faithful in his Palm Sunday homily a few years ago, “It is precisely here that his kingship shines forth in godly fashion: his royal throne is the wood of the Cross!”

A book entitled Stories for the Heart was published a few years ago by inspirational speaker Alice Gray. It is a compilation of what Gray calls “stories to encourage your soul;” one of them is the following story, whose original author she says is unknown. It may not be true, but I (for one) hope it is:

A book entitled Stories for the Heart was published a few years ago by inspirational speaker Alice Gray. It is a compilation of what Gray calls “stories to encourage your soul;” one of them is the following story, whose original author she says is unknown. It may not be true, but I (for one) hope it is: