====================

A homily offered by the Rev. Dr. C. Eric Funston on the Nineteenth Sunday after Pentecost, September 25, 2016, to the people of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Medina, Ohio, where Fr. Funston is rector.

(The lessons for the day are Proper 21C of the Revised Common Lectionary: Amos 6:1a,4-7; Psalm 146; 1 Timothy 6:6-19; and St. Luke 16:19-31. These lessons may be found at The Lectionary Page.)

====================

![Dives and Lazarus. Psalter (Munich Golden Psalter). England [Gloucester?], 1st quarter of the 13th century.](http://thefunstons.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/Lazarus-and-Dives-300x264.jpg) We could, I suppose, spiritualize the story of Lazarus and the rich man. We could, but if we did we would be twisting it out of shape. This is not a spiritual story. This is a bare-knuckled street-brawl of a story about wealth, about money and possessions, about someone who had plenty and about someone who had none. If we are going to honor the biblical text, we cannot spiritualize this tale; we have to deal with it as it is given us, as a story about money.

We could, I suppose, spiritualize the story of Lazarus and the rich man. We could, but if we did we would be twisting it out of shape. This is not a spiritual story. This is a bare-knuckled street-brawl of a story about wealth, about money and possessions, about someone who had plenty and about someone who had none. If we are going to honor the biblical text, we cannot spiritualize this tale; we have to deal with it as it is given us, as a story about money.

Did you know that the rich man has a name? Not in the Bible, I grant you that, but in the tradition of the church he is known as “Dives” – D-I-V-E-S pronounced “Dye-veez”. That name comes from the Latin “Vulgate” translation completed by St. Jerome in the late 4th Century in which he translated the Greek word for “rich,” plousios – which means “one who possesses wealth” – with the Latin word dives (pronounced “Dee-vase” in this context) – which comes from the same root as our word “divine” and means “one who is favored by the gods.”

In the Bible, of course, only the poor man is actually given a name, Lazarus. This is the Latinized version of the Greek transliteration of a Hebrew name, Eliezer. This name, it turns out, means “one who is aided by God.”

So, in the church’s tradition, both biblical and magisterial, these men have the same name! “Favored by God” . . . “Aided by God” . . . they are both named as beloved children of God, helped by God, bestowed by God with God’s grace and love. That is why we cannot spiritualize this story. Spiritually, there is no difference between these two men; they stand in the same relationship to God who, interestingly enough, isn’t even mentioned in the story. This not a story about God; it’s a story about money.

Which makes perfect sense when we consider where it comes in Luke’s gospel and in our lectionary sequence of readings. Let’s just go back a few chapters:

In chapter 12 Jesus told the story of Barn Guy, the rich man who had a great year with bumper crops and lots of lambs and calves, thought he could keep his earnings all to himself, and built bigger barns to keep it in . . . only to be told that he was going to die and learns, as Paul writes to Timothy in today’s epistle, “we brought nothing into the world, so that we can take nothing out of it,” so the best we can do is use our wealth to do good in this world.

In chapter 13, he talks about two trees both understood to be metaphors for God’s people and God’s kingdom: a barren fig tree which the owner decides to cut down and a mustard tree which starts from small beginnings but soon grows to provide shelter not only for the one who sowed it but for everyone.

In chapter 14, Jesus commands his followers to count the cost of following him and then tells them (that is to say, us) what that cost is: that until we sell all of our possessions and give the proceeds to the poor we are not worthy to follow him.

In chapter 15, we heard the parables of the shepherd who sought one lost sheep to complete his herd of 100 and of the woman who cleaned her whole house to find the one missing coin to complete her purse of 10, and then Jesus told us about the Prodigal who squandered all his wealth . . . but was nonetheless welcomed home with love and respect!

Now in chapter 16, we had last week’s weird story in which Jesus praised the dishonest steward who told his boss’s debtors to falsify the record of what they owed; Jesus’ punchline was that we should use our earthly wealth to win friends to welcome us “into the eternal homes.” Now he tells us this story about Dives who didn’t do that and wasn’t welcomed by Lazarus whom he might have helped or by Father Abraham, who (by the way) was quite a wealthy guy himself but clearly not sympathetic to Dives. (You know, it occurred to me that Dives could be Barn Guy. Jesus could have said, “Remember that guy who was really well off, had that great harvest, and built those new barns, but didn’t share his good fortune with anyone? Well, let me tell you about what happened after he died that night . . . .”)

Now, as I said, we could spiritualize all these stories and try to make them about God, but if we did that we’d have to wonder about Jesus, wouldn’t we? I mean the man has used stories about money so often that we would have to think that he must be unable to come up with another metaphor . . . or we would have to conclude that he doesn’t mean it to be a metaphor, at all. I think we have to reach the second conclusion and to understand, as Paul does, that Jesus believes “the love of money is a root of all kinds of evil,” and that those who have wealth are expected “to do good, to be rich in good works, generous, and ready to share, thus storing up for themselves the treasure of a good foundation for the future, so that they may take hold of the life that really is life.”

“What’s implied here is that places in the kingdom [‘the life that really is life’] are not given out according to what we have, but according to what we give away. What counts is solidarity; what counts is love. [Dives] who made a name for himself but didn’t care enough to share his wealth has no name any more. [Lazarus] who couldn’t achieve a thing all his life has been given a name of honor.” (Wendt, F., The Politics of a Name)

So let’s talk about money. Throughout his life, Jesus showed love, compassion, and care for those who didn’t have any, those who were at the bottom of society, namely the poor, the sick, the outcast, the foreigner, and those whom others considered to be sinners because of their poverty. However, he never condemned anyone for having money; what Jesus seems to have been most concerned about in regard to the wealthy was their reliance on money to provide security, a security which is ultimately temporary because wealth cannot provide that ultimate security found only in God. What is condemned is the love of money, the putting of wealth into that place in our lives where God ought to be.

Therefore, it would be “inappropriate to affirm in a wholesale fashion that [Jesus or the] early Christians criticized material wealth. Instead, of crucial importance is the attitude of the person owning it. Material wealth can get in the way of putting one’s trust in God, and it can be a hindrance to following Jesus. Yet [we must admit that all of our] church ministries and services depend on the financial resources of those who are willing [and able] to share them.” (Eberhart, C.A., Commentary on 1 Timothy 6:6-19)

I want to repeat here what I wrote in this week’s parish up-date email and what I will publish again in the October issue of our newsletter:

It is this sharing of resources that God wants of us. Clearly, God doesn’t want us to be self-reliant and, frankly, selfish rich people like Dives, but God also doesn’t want us all to be poor, sore-covered, gutter-dwelling beggars like Lazarus. What God does want us to do is to share with one another and with God in the ministries of the church.

When Bishop Hollingsworth visits here in a month (on October 30), we will, as we do at each service of baptism or confirmation, affirm our agreement to that partnership by reciting five vows from the Baptismal Covenant:

- Will you continue in the apostle’s teaching and fellowship, in the breaking of bread, and in the prayers?

- Will you persevere in resisting evil, and, whenever you fall into sin, repent and return to the Lord?

- Will you proclaim by word and example the Good News of God in Christ?

- Will you seek and serve Christ in all persons, loving your neighbor as yourself?

- Will you strive for justice and peace among all people, and respect the dignity of every human being?

To each question, we respond: “I will, with God’s help.”

When we recite our baptismal vows, we are renewed in and reminded of God’s call in our lives and the life of St. Paul’s Parish. We are all God’s partners by virtue of our baptism, and we are all called by God to proclaim, in word and action, God’s justice, love and mercy for all creation, to do God’s work right here on earth.

Ministry, outreach, worship, baptisms, marriages, funerals, visiting the sick, praying for family and friends, offering spiritual and religious formation, helping those less fortunate than ourselves – doing these things in and through our church is part of our partnership with God. And each one of them costs money. God provides us with inspiration, skill, vision, and determination. But we have to provide the money.

Over the next six weeks, we will talking a lot about money. You will be asked to think about your support of St. Paul’s Parish for the next year. You will be asked to make your pledge of financial support for 2017. You will be asked to act on your promised partnership with God. Think of all your regular gift of money can do for our church, for our families, and (most importantly) for our neighbors. Think of all it can do for our partnership work with God here on earth. It is through our pledges, faithfully made and faithfully kept, that we partner with God to tell the good news, take care of children, visit the elderly, heal the sick, house the homeless, feed the hungry, and (yes) maintain our most important tool in doing all of that, this lovely building within which we worship today.

That’s what our pledged financial support does; that is what our sharing of our wealth does: God’s work in which we are partners. God expects us to live generously as God lives generously with us.

Like Dives, we are all favored by God. Like Lazarus, we are all aided by God. We stand in the same relationship to God as they did. In a sense, we are Dives’ siblings, those five brothers he asked that Father Abraham send Lazarus to warn. “We who are still alive have been warned about our urgent situation, the parable makes clear. We have Moses and the prophets; we have the scriptures; we have the manna lessons of God’s economy, about God’s care for the poor and hungry. We even have someone who has risen from the dead. The question is: Will we – [Dives’] sisters and brothers – see? Will we heed the warning, before it is too late?” (Rossing, B., Commentary on Luke 16:19-31) Will we who have the God of Jacob for our help, whose hope is in the Lord our God, whose God richly provides us with everything for our enjoyment . . . will we live generously and fulfill our promises of partnership with God?

I believe we will.

Let us pray:

Gracious and generous God,

your Son came that we might have life

and have it abundantly,

we pledge our trust in you and each other,

and we accept your invitation to be partners in ministry.

We acknowledge that your call requires us

to be stewards of your gifts,

shaping our lives in imitation of Jesus,

whom we have promised to follow.

As stewards, we receive your gifts gratefully,

cherish and tend them in a responsible manner,

share them by living generously with others,

and return them with increase to you, our Lord.

We pledge to attend to our ongoing formation as stewards

and our responsibility to call others to that same endeavor.

Almighty and ever-faithful God,

we are grateful

that you who have begun this good work in us

and will bring it to fulfillment

in Jesus Christ, our Lord. Amen.

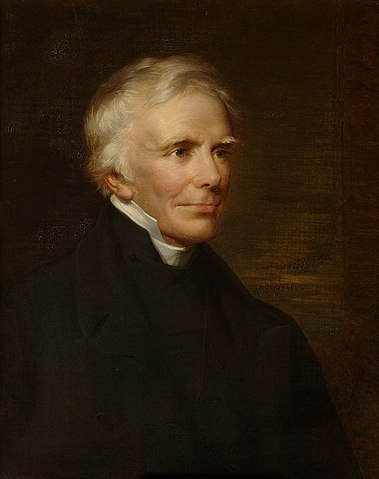

[The illustration is “Dives and Lazarus” from the Munich Golden Psalter, dating from the 1st quarter of the 13th century.]

====================

A request to my readers: I’m trying to build the readership of this blog and I’d very much appreciate your help in doing so. If you find something here that is of value, please share it with others. If you are on Facebook, “like” the posts on your page so others can see them. If you are following me on Twitter, please “retweet” the notices of these meditations. If you have a blog of your own, please include mine in your links (a favor I will gladly reciprocate). Many thanks!

====================

Father Funston is the rector of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Medina, Ohio.

I understand that St. Andrew’s Parish is, today, beginning its annual stewardship campaign, so I suppose it’s appropriate that we heard the story of Jesus being confronted by the wealthy man who wants to inherit eternal life in today’s Gospel reading from Mark. This tale must have been an important one to the earliest Christians, because we find it in all three of the Synoptic Gospels. Mark tells us only that the man is wealthy; Matthew adds that he is young; and Luke informs us that he is a ruler of some sort. But none of those details really changes the basic nature of the encounter: a potential disciple comes to Jesus seeking guidance and Jesus tells him that he must give up everything he possesses – “You lack one thing; go, sell what you own, and give the money to the poor….”[1] The obligations of discipleship, in other words, are total.

I understand that St. Andrew’s Parish is, today, beginning its annual stewardship campaign, so I suppose it’s appropriate that we heard the story of Jesus being confronted by the wealthy man who wants to inherit eternal life in today’s Gospel reading from Mark. This tale must have been an important one to the earliest Christians, because we find it in all three of the Synoptic Gospels. Mark tells us only that the man is wealthy; Matthew adds that he is young; and Luke informs us that he is a ruler of some sort. But none of those details really changes the basic nature of the encounter: a potential disciple comes to Jesus seeking guidance and Jesus tells him that he must give up everything he possesses – “You lack one thing; go, sell what you own, and give the money to the poor….”[1] The obligations of discipleship, in other words, are total.  The United States is, at least ostensibly, a very religious country. Nearly two hundred years ago, Alexis de Tocqueville wrote that “there is no country in the world where … religion retains a greater influence over the souls of men than in America; and there can be no greater proof of its utility and its conformity to human nature than that its influence is powerfully felt over the most enlightened and free nation of the earth.”

The United States is, at least ostensibly, a very religious country. Nearly two hundred years ago, Alexis de Tocqueville wrote that “there is no country in the world where … religion retains a greater influence over the souls of men than in America; and there can be no greater proof of its utility and its conformity to human nature than that its influence is powerfully felt over the most enlightened and free nation of the earth.” We have three intriguing lessons from scripture today. First we have a denunciation of Hebrew worship, which also interestingly contains a verse most famous in American politics for having been spoken on the steps of the Lincoln monument by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Some people who dislike liturgy, or some aspect of liturgy, like incense, or vestments or music, ignoring that sentence about justice flowing like streams, have used this text to prove that God also dislikes, liturgy, or incense, or vestments, or whatever. However, that’s not what this lesson is about and I’ll get back to that in just a moment.

We have three intriguing lessons from scripture today. First we have a denunciation of Hebrew worship, which also interestingly contains a verse most famous in American politics for having been spoken on the steps of the Lincoln monument by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Some people who dislike liturgy, or some aspect of liturgy, like incense, or vestments or music, ignoring that sentence about justice flowing like streams, have used this text to prove that God also dislikes, liturgy, or incense, or vestments, or whatever. However, that’s not what this lesson is about and I’ll get back to that in just a moment.  When I was in the 8th Grade, I attended Robert Fulton Junior High School in Van Nuys, California, which is in the San Fernando Valley area of the Los Angeles metroplex. At some point during the year, Mrs. R. Smith, who taught English, gave my class an assignment to memorize and interpret a poem; we had to get up in front of the class, recite the poem, and then give our interpretation. When it came to be my turn, I recited my chosen poem, said what I believed it meant, and explained my interpretation. Mrs. Smith responded, “Your interpretation is wrong,” to which I replied, “I can interpret a poem any damned way I please!”

When I was in the 8th Grade, I attended Robert Fulton Junior High School in Van Nuys, California, which is in the San Fernando Valley area of the Los Angeles metroplex. At some point during the year, Mrs. R. Smith, who taught English, gave my class an assignment to memorize and interpret a poem; we had to get up in front of the class, recite the poem, and then give our interpretation. When it came to be my turn, I recited my chosen poem, said what I believed it meant, and explained my interpretation. Mrs. Smith responded, “Your interpretation is wrong,” to which I replied, “I can interpret a poem any damned way I please!” Yesterday, July 14, was the 185th anniversary of the preaching a sermon which is said to have been the beginning of the Catholic revival in the Church of England. The sermon was preached at St. Mary’s Church Oxford by the Rev. John Keble, Provost of Oriel College and Professor of Poetry at Oxford. The sermon marked the opening of the Assize Court, the summer term of the English High Court of Justice. The Assize sermon normally would have addressed matters of law and religion, but in the summer of 1833 the Parliament of the United Kingdom was debating whether to abolish (or in the language of the time “suppress”) some dioceses of the Anglican Church of Ireland which, at the time, was united with the Church of England. It was an entirely financial issue in the eyes of Parliament, but Keble and several of his friends believed this to be an encroachment of the secular establishment upon the religious and an altogether wrong thing, and so it was this portending legislation that Keble addressed in his homily, which he titled National Apostasy. He began with these words:

Yesterday, July 14, was the 185th anniversary of the preaching a sermon which is said to have been the beginning of the Catholic revival in the Church of England. The sermon was preached at St. Mary’s Church Oxford by the Rev. John Keble, Provost of Oriel College and Professor of Poetry at Oxford. The sermon marked the opening of the Assize Court, the summer term of the English High Court of Justice. The Assize sermon normally would have addressed matters of law and religion, but in the summer of 1833 the Parliament of the United Kingdom was debating whether to abolish (or in the language of the time “suppress”) some dioceses of the Anglican Church of Ireland which, at the time, was united with the Church of England. It was an entirely financial issue in the eyes of Parliament, but Keble and several of his friends believed this to be an encroachment of the secular establishment upon the religious and an altogether wrong thing, and so it was this portending legislation that Keble addressed in his homily, which he titled National Apostasy. He began with these words: Our kids this week have been “Shipwrecked,” but they’ve also been “rescued by Jesus.”

Our kids this week have been “Shipwrecked,” but they’ve also been “rescued by Jesus.” Almighty God, on this day you opened the way of eternal life to every race and nation by the promised gift of your Holy Spirit who empowered the disciples to proclaim the Good News to peoples from many lands speaking many tongues: we now pray for those in many lands speaking many languages who have been hurt or killed by terrorist violence in the past fortnight in: London (England), Kabul (Afghanistan), Mosel (Iraq), Minya (Egypt), Khost (Afghanistan), Mastung (Pakistan), Gao (Mali), Borno State (Nigeria), Raqqa (Syria), Mogadishu (Somalia), rural Colombia, Manila (Philippines), Baghdad (Iraq), Basra (Iraq), Portland (Oregon, USA) and Manchester (England). May God grant eternal rest to the departed, healing to the injured, and comfort to those in grief. And since Jesus taught us to love and pray for our enemies, we pray also for those who have committed these violent acts, and for those who may be contemplating additional violence. May God change their hearts and shed abroad the gift of peace throughout the world by the preaching of the Gospel, that it may reach to the ends of the earth; through Jesus Christ our Lord, who lives and reigns with you, in the unity of the Holy Spirit, one God, for ever and ever. Amen.

Almighty God, on this day you opened the way of eternal life to every race and nation by the promised gift of your Holy Spirit who empowered the disciples to proclaim the Good News to peoples from many lands speaking many tongues: we now pray for those in many lands speaking many languages who have been hurt or killed by terrorist violence in the past fortnight in: London (England), Kabul (Afghanistan), Mosel (Iraq), Minya (Egypt), Khost (Afghanistan), Mastung (Pakistan), Gao (Mali), Borno State (Nigeria), Raqqa (Syria), Mogadishu (Somalia), rural Colombia, Manila (Philippines), Baghdad (Iraq), Basra (Iraq), Portland (Oregon, USA) and Manchester (England). May God grant eternal rest to the departed, healing to the injured, and comfort to those in grief. And since Jesus taught us to love and pray for our enemies, we pray also for those who have committed these violent acts, and for those who may be contemplating additional violence. May God change their hearts and shed abroad the gift of peace throughout the world by the preaching of the Gospel, that it may reach to the ends of the earth; through Jesus Christ our Lord, who lives and reigns with you, in the unity of the Holy Spirit, one God, for ever and ever. Amen.![Dives and Lazarus. Psalter (Munich Golden Psalter). England [Gloucester?], 1st quarter of the 13th century.](http://thefunstons.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/Lazarus-and-Dives-300x264.jpg) We could, I suppose, spiritualize the story of Lazarus and the rich man. We could, but if we did we would be twisting it out of shape. This is not a spiritual story. This is a bare-knuckled street-brawl of a story about wealth, about money and possessions, about someone who had plenty and about someone who had none. If we are going to honor the biblical text, we cannot spiritualize this tale; we have to deal with it as it is given us, as a story about money.

We could, I suppose, spiritualize the story of Lazarus and the rich man. We could, but if we did we would be twisting it out of shape. This is not a spiritual story. This is a bare-knuckled street-brawl of a story about wealth, about money and possessions, about someone who had plenty and about someone who had none. If we are going to honor the biblical text, we cannot spiritualize this tale; we have to deal with it as it is given us, as a story about money. This morning, after I took the dog for her walk and poured a cup of coffee, I turned on my computer and found a message from my friend Melania, who is from Naples but is currently working in Spain. We were students together in Ireland. This is her message:

This morning, after I took the dog for her walk and poured a cup of coffee, I turned on my computer and found a message from my friend Melania, who is from Naples but is currently working in Spain. We were students together in Ireland. This is her message: