====================

A sermon offered on the Second Sunday of Advent, December 6, 2015, to the people of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Medina, Ohio, where Fr. Funston is rector.

(The lessons for the day are Baruch 5:1-9; Canticle 16 [Luke 1: 68-79]; Philippians 1:3-11; and Luke 3:1-6. These lessons may be found at The Lectionary Page.)

====================

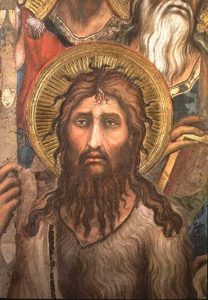

It’s the Second Sunday of Advent so according to our lectionary tradition, we hear the words of John the Baptizer, the voice of one crying in the desert, calling us to clean up the roadways and build a straight path for God’s coming. We are all familiar with the Baptizer. He’s some sort of cousin of Jesus. He’s a bit of a wild man; he lives in the wilderness wearing rough clothing and eating only what foods he can pick from desert plants and animals, “locusts and wild honey” is the way the evangelists put it. This year we hear Luke’s version of John’s story.

It’s the Second Sunday of Advent so according to our lectionary tradition, we hear the words of John the Baptizer, the voice of one crying in the desert, calling us to clean up the roadways and build a straight path for God’s coming. We are all familiar with the Baptizer. He’s some sort of cousin of Jesus. He’s a bit of a wild man; he lives in the wilderness wearing rough clothing and eating only what foods he can pick from desert plants and animals, “locusts and wild honey” is the way the evangelists put it. This year we hear Luke’s version of John’s story.

Later in his gospel story, Luke relates a tale of Jesus angrily denouncing the leadership in the towns of Galilee who refused to listen either to the Baptizer or to Jesus. Jesus says to them: “John the Baptist has come eating no bread and drinking no wine, and you say, ‘He has a demon’; the Son of Man has come eating and drinking, and you say, ‘Look, a glutton and a drunkard….’” (Lk 7:33-34) John refused to eat bread, but for Jesus bread is an important element of his ministry; he even taught us to pray for it. So, today, we continue our examination of the Lord’s Prayer with the next petition: “Give us today our daily bread.”

Why do you suppose John refused to eat this staple food that Jesus found so important? There are two related reasons. The first is that bread and wine are processed foods associated with settled communities; for John, as for many prophets, the settled communities were places of corruption. John would have nothing to do with corrupt society and bread, for him, was a symbol of that society.

Luke tells us very clearly in political terms when John appeared on the scene. He situates the advent of the Baptizer and his revelation in the temporal context of the native ruler Herod, the local but foreign governor Pilate, and the final authority who sits above all, Tiberius. Our translation says it was during the “reign” of Tiberius, the “governorship” of Pilate, and the “rule” of Herod. However, the word Luke uses for Herod’s dominion is “tetrarchy” and for both Pilate’s and Tiberius’s governance, his word is “hegemony” (hegemoneuo and hegemonia, respectively). “Tetrarchy” refers to the fact that imperial Rome had divided Palestine into four arbitrarily defined regions and imposed on them the rule of puppet kings. “Hegemony” denotes a kind of imperial governance in which political domination is maintained by military force. In other words, Luke describes the very sort of corrupt and unjust political society that John eschewed and symbolically rejected by his refusal to eat bread.

John’s prophetic message is a call to build a straight, level, and smooth road for God, but as the scribe Baruch points out that road will be a two-way street. As Baruch puts it, “God has ordered that every high mountain and the everlasting hills be made low and the valleys filled up, to make level ground, so that Israel may walk safely in the glory of God.” On that road, says Baruch, “God will lead Israel with joy, in the light of his glory, with the mercy and righteousness that come from him.” In other words, the justice which John found lacking in settled communities and in the hegemonic domination of imperial Rome will be found on the road prepared in the desert.

The second, related reason that John will not eat bread has to do with ritual impurity. The Jewish Virtual Library’s commentary on the Baptizer tells us, “The reference to John not eating bread or wine probably indicates that John preferred to eat foods that had not been processed by human hands and would not therefore be susceptible to impurity. For this same reason John was said to have eaten locusts and honey (Matt. 3:4), both of which were regarded by his fellow Jews as pure items of food.”

In many ways, John and Jesus were polar opposites. They seem to have had the same goal, the restoration of justice and righteousness in Israel, but their approaches were very different. If John was overly fastidious about ritual purity, Jesus doesn’t seem to have given a hoot about it! He regularly dined with tax collectors and outcasts, allowed prostitutes to touch him, touched dead bodies, conversed with gentile women, and allowed his disciples to eat without washing their hands (and presumably did the same himself). He just doesn’t seem to have cared much about the purity laws.

But Jesus did care about justice and for Jesus that is precisely what bread represents. If bread was John’s symbol for corrupt and unjust hegemony, for Jesus bread is the sign and symbol of divine righteousness and justice. He would even say of himself that he is “the bread of God . . . which comes down from heaven and gives life to the world;” “I am the bread of life.” (Jn 6:33,48)

I believe that a poem by the anti-Nazi poet and playwright Bertolt Brecht would have resonated for Jesus; it is entitled The Bread of the People:

Justice is the bread of the people

Sometimes is plentiful, sometimes it is scarce

Sometimes it tastes good, sometimes it tastes bad.

When the bread is scarce, there is hunger.

When the bread is bad, there is discontent.

Throw away the bad justice

Baked without love, kneaded without knowledge!

Justice without flavour, with a grey crust

The stale justice which comes too late!

If the bread is good and plentiful

The rest of the meal can be excused.

One cannot have plenty of everything all at once.

Nourished by the bread of justice

The work can be achieved

From which plenty comes.

As daily bread is necessary

So is daily justice.

It is even necessary several times a day.

From morning till night, at work, enjoying oneself.

At work which is an enjoyment.

In hard times and in happy times

The people requires the plentiful, wholesome

Daily bread of justice.

Since the bread of justice, then, is so important

Who, friends, shall bake it?

Who bakes the other bread?

Like the other bread

The bread of justice must be baked

By the people.

Plentiful, wholesome, daily.

“The bread of justice must be baked by the people” just as the road in the desert, the straight, level, smooth road of justice and righteousness must be cleared and built by God’s people.

Jesus taught us to pray for this bread, the bread of justice, daily in the Lord’s Prayer: “Give us today our daily bread.” This is a petition for more than food, for more than nourishment.

There is, hidden in this petition, one of the strangest words in the New Testament. It is the word which our English bibles translate as “daily” although it doesn’t actually mean that. It is translated that way because, in all honesty, no one is exactly sure what it means. The word, in Greek, is epiousion; it is a compound word made up of a root meaning “substance” or “being” (ousion) and a prefix meaning “over” or “above” (epi). It is what linguistics scholars call a hapax legomenon, “something said only once.” The word epiousion appears only in the New Testament Gospels, and only in this line of the Lord’s Prayer as recorded by both Luke and Matthew.

What is it meant to convey? No one knows. The Gospel writers were reporting in Greek something Jesus said probably in Aramaic, but no scholar has ever been able to suggest an Aramaic original. Translating the Greek backwards into Aramaic yields no intelligible clue. When the first translators of the Scriptures from Greek into Latin undertook their task, being ignorant of the word’s actual meaning (whatever it may be), they took a hint from the words just before it in the text – “this day” in Matthew, “each day” in Luke – and rendered it as quotidian, which means “daily”. And thus it entered the liturgical rendition of the prayer known to us.

St. Jerome, however, when he undertook his new translation into Latin, refused to guess. He simply rendered the Greek into equivalent Latin, creating the term supersubstantialem, “supersubstantial”. “Give us today our supersubstantial bread.” Whatever do you suppose that might be?

Even though he refused to translate it, St. Jerome had two suggestions for how to understand it. First he suggested “that it means ‘for tomorrow’ so that the meaning here is ‘give us this day our bread for tomorrow’ that is, for the future.” (Commentary on Matthew 1.6.11) In this sense, this petition could be understood as a prayer for God’s abundance. Jerome’s second suggestion is that it means that “bread which is above all substances and surpasses all creatures.” (Ibid.) He seems particularly to have had in mind the Holy Eucharist.

Now I would make no claim to greater scholarship than St. Jerome, but I do want to suggest another connection that may have been there for Jesus, and that is the bread of the Passover feast, the Seder. Among some Jews today, during the ritual of the unleavened bread or matzah, each person is invited to hold a piece of matzah. The leader of the ritual says: “This is the bread of affliction which our ancestors ate in the land of Egypt.” Then in silence all break their matzot in half and they listen to the sound of the bread of affliction cracking open. All then say together:

May our eyes be open to each other’s pain.

May our ears be open to each other’s cries.

May we live with greater awareness.

May we practice greater forgiveness.

And may we go forward as free people

able to respond to ourselves and to each other

with compassion, wonderment, appreciation, and love.

All of the broken matzah are put together on a single plate and the prayer continues:

Let all who are hungry come and eat.

Let all who are in need join us in this Festival of Liberation.

May each of us, may all of us, find our homes.

May each of us, may all of us, be free.

In this ritual of the Seder, the matzah is understood to be changed. It ceases to be the bread of affliction and is transformed into the bread of hope, courage, faith, and possibility. The bread of affliction becomes something greater than it was, something above its original being, something more than its original substance; it becomes the bread of justice.

This, I suggest, is what Jesus taught us to pray for on a daily basis, the bread of affliction transformed into more than its original substance, something greater than its original being, the supersubstantial bread of justice.

Just as the road in the desert, the straight, level, smooth road of justice and righteousness called for by the Baptizer must be cleared and built by God’s people, so “the bread of justice must be baked by the people.” That for which Jesus teaches us to pray each day, we must do the hard work of creating: hope and courage, faith and possibility, righteousness and justice.

Give us today our daily bread. Amen.

====================

A request to my readers: I’m trying to build the readership of this blog and I’d very much appreciate your help in doing so. If you find something here that is of value, please share it with others. If you are on Facebook, “like” the posts on your page so others can see them. If you are following me on Twitter, please “retweet” the notices of these meditations. If you have a blog of your own, please include mine in your links (a favor I will gladly reciprocate). Many thanks!

====================

Father Funston is the rector of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Medina, Ohio.

When I was a kid growing up first in southern Nevada and then in southern California, the weeks leading up to Christmas (we weren’t church members so we didn’t call them “Advent”) were always the same. They followed a pattern set by my mother. We bought a tree and decorated it; we set up a model electric train around it. We bought and wrapped packages and put them under the tree, making tunnels for that toy train. We went to the Christmas light shows in nearby parks and drove through the neighborhoods that went all out for cooperative, or sometimes competitive, outdoor displays. My mother would make several batches of bourbon balls (those confections made of crushed vanilla wafers and booze) and give them to friends and co-workers. Christmas Eve we would watch one or more Christmas movies on TV, and early Christmas morning we would open our packages . . . carefully so that my mother could save the wrapping paper. Then all day would be spent cooking and watching TV and playing bridge. After the big Christmas dinner, my step-father and I would do the clean up, my brother and my uncle would watch TV . . . and my mother would sneak off to her room and cry. You see . . . no matter how carefully we prepared, no matter how strictly we adhered to Mom’s pattern, something always went wrong. We never got it right; Christmas never turned out the way my mother wanted it to be.

When I was a kid growing up first in southern Nevada and then in southern California, the weeks leading up to Christmas (we weren’t church members so we didn’t call them “Advent”) were always the same. They followed a pattern set by my mother. We bought a tree and decorated it; we set up a model electric train around it. We bought and wrapped packages and put them under the tree, making tunnels for that toy train. We went to the Christmas light shows in nearby parks and drove through the neighborhoods that went all out for cooperative, or sometimes competitive, outdoor displays. My mother would make several batches of bourbon balls (those confections made of crushed vanilla wafers and booze) and give them to friends and co-workers. Christmas Eve we would watch one or more Christmas movies on TV, and early Christmas morning we would open our packages . . . carefully so that my mother could save the wrapping paper. Then all day would be spent cooking and watching TV and playing bridge. After the big Christmas dinner, my step-father and I would do the clean up, my brother and my uncle would watch TV . . . and my mother would sneak off to her room and cry. You see . . . no matter how carefully we prepared, no matter how strictly we adhered to Mom’s pattern, something always went wrong. We never got it right; Christmas never turned out the way my mother wanted it to be. “Take off the garment of your sorrow and affliction, O Jerusalem, and put on forever the beauty of the glory from God.”

“Take off the garment of your sorrow and affliction, O Jerusalem, and put on forever the beauty of the glory from God.” It’s the Second Sunday of Advent so according to our lectionary tradition, we hear the words of John the Baptizer, the voice of one crying in the desert, calling us to clean up the roadways and build a straight path for God’s coming. We are all familiar with the Baptizer. He’s some sort of cousin of Jesus. He’s a bit of a wild man; he lives in the wilderness wearing rough clothing and eating only what foods he can pick from desert plants and animals, “locusts and wild honey” is the way the evangelists put it. This year we hear Luke’s version of John’s story.

It’s the Second Sunday of Advent so according to our lectionary tradition, we hear the words of John the Baptizer, the voice of one crying in the desert, calling us to clean up the roadways and build a straight path for God’s coming. We are all familiar with the Baptizer. He’s some sort of cousin of Jesus. He’s a bit of a wild man; he lives in the wilderness wearing rough clothing and eating only what foods he can pick from desert plants and animals, “locusts and wild honey” is the way the evangelists put it. This year we hear Luke’s version of John’s story. It’s Christmas Eve! Probably my busiest and longest workday of the year.

It’s Christmas Eve! Probably my busiest and longest workday of the year.