====================

This sermon was preached on Sunday, February 17, 2013, at St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Medina, Ohio, where Fr. Funston is rector.

(Revised Common Lectionary, Lent 1, Year C: Deuteronomy 26:1-11; Psalm 91:1-2,9-16; Romans 10:8b-13; and Luke 4:1-13. These lessons can be read at The Lectionary Page.)

====================

In The Book of Common Prayer on page 264 you’ll find the beginning of the liturgy for Ash Wednesday. If you were here on that day which marks the beginning of this season we call Lent, or in another church to be marked on your forehead with the cross of ashes, to be reminded of your mortality with the familiar words, “Remember you are dust, and to dust you will return,” you will also have heard the Lenten admonition which the presiding priest reads at each Ash Wednesday service. It begins at the bottom of that page and comes in the service after the reading of the lessons of the day and the preaching of the sermon.

In The Book of Common Prayer on page 264 you’ll find the beginning of the liturgy for Ash Wednesday. If you were here on that day which marks the beginning of this season we call Lent, or in another church to be marked on your forehead with the cross of ashes, to be reminded of your mortality with the familiar words, “Remember you are dust, and to dust you will return,” you will also have heard the Lenten admonition which the presiding priest reads at each Ash Wednesday service. It begins at the bottom of that page and comes in the service after the reading of the lessons of the day and the preaching of the sermon.

It seems to me that many of us hear those words, perhaps even read along with them (as is our wont as Episcopalians), but I wonder to what extent we actually think about them, consider them, and internalize them. So this morning, as we enter into the Sundays which are in Lent but not of Lent, I’d like to return to Ash Wednesday and look more closely at, and perhaps offer a few cogent comments about, the Ash Wednesday admonition.

Dear People of God, . . . .

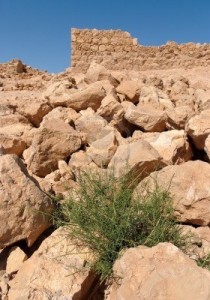

. . . . it starts and let’s just stop there and consider what that means. We hear those words, “the People of God,” often in Scripture, and when we do we usually understand it to mean those people long ago, those folks who lived way back then 2,000 or 3,000 or more years ago and way over there in the deserts of the Middle East in Palestine or Judea or Israel or Syria. “The People of God,” we think, are the Hebrews, those folks who Moses helped get their freedom from Pharaoh in Egypt, the ones to whom Moses is talking in the reading from Deuteronomy this morning. Or, perhaps, we believe “the People of God” are the descendants of Abraham, that “wandering Aramean” whom Moses’ audience was to claim as their ancestor. Or, again, maybe we think of the modern Jews as “the People of God,” the Chosen people with whom God has that special covenant.

But here we are addressed in the liturgy of Ash Wednesday as if we are the People of God! Do we think of ourselves that way? And more specifically, does each of us think of him- or herself individually as a “person of God”?

Did you know that that one of my titles, one of the names of the office of ministry in which I work, actually comes from that term? The word “parson,” which describes a parish priest or village clergyman comes from the old or middle English version of the word “person”. The medieval parish priest was the “person of God,” the “parson,” whose job it was to be in the church praying the liturgical hours, offering the sacrifice of the Mass, looking after the spiritual business of the community so the rest of the people wouldn’t have to! They could get on with the planting of crops, the tilling of fields, the harvesting of produce, the care and feeding of livestock. They could do all the other things of daily life and then go to the pub and have a beer because the “parson,” the “person of God” would have have taken care of the religious stuff, the spiritual stuff for them.

That is not, however, the way it’s supposed to be because no one person is the “person of God” — we are all “people of God;” we are all “persons of God.”

The first Christians observed with great devotion the days of our Lord’s passion and resurrection . . .

Now pay close attention to that! The focus of Lent is not Lent! The focus of Lent is “our Lord’s passion and resurrection.” The focus of Lent is Maundy Thursday and Jesus’ agonizing night of prayer in the garden at Gethsemane. The focus of Lent is Good Friday and his terrible, tortured death on the cross of Calvary. The focus of Lent is Holy Saturday and his burial in the borrowed tomb, his descent into hell, his freeing the souls of the dead. The focus of Lent is the empty tomb of Easter morning, his resurrection, his fifty days on earth appearing to, teaching, and sending forth his apostles. The focus of Lent is his Ascension into heaven to be always alive and always with us, our great high priest eternally pleading our case before the Father, elevating our humanity into divinity. Lent is never about Lent! Lent is always looking forward. Lent is always about Easter and beyond.

. . . . and it became the custom of the Church to prepare for them by a season of penitence and fasting. This season of Lent . . . .

As many of you know, I was not reared in the Episcopal Church . . . I wasn’t really brought up in any religious tradition. On one side, my mother’s, the family were part of the Campbellite tradition, out of which the Disciples of Christ is the largest current denominational body; they didn’t know from Adam about the church year, about Lent or any other season. On my father’s side they were Methodists in the old Methodist Episcopal (South) mold; no liturgical seasons for them! So we didn’t do this Lent thing. I had Catholic classmates in grade school, of course. I knew they were Catholic because they would show up at school on Ash Wednesday morning having come from Mass with a smudge of ash on their foreheads; they were doing Lent.

But the only thing I knew about “Lent” was that in the sort of English my grandmother spoke it was the past tense of the verb “to lend”. I thought the Roman Catholics were maybe paying back to God something they had borrowed from God. And, you know what? That’s not far from being a good description of what Lent is, in fact, all about. In our lesson from Deuteronomy today that is exactly what Moses instructs the people who are about to enter into the Promised Land, these Hebrews which he has led from captivity in Egypt. They are to remember that everything they have or ever will have has been given to them by God, through no merit of their own; they are to return to God at least some portion, the “first fruits”, of that which God has lent to them.

This season of Lent provided a time in which converts to the faith were prepared for Holy Baptism.

Did you know that back in the beginning, before the Emperor Constantine made Christianity first legal and then the official religion of the Roman Empire, it was a big deal to become a Christian? It was a dangerous thing because it was illegal, and Christians were often blamed for the Empire’s problems and made scapegoats, imprisoned, tortured, and killed. One could not simply walk into a congregation and ask to become a member. You had to be instructed and tested, and often it took as long as three years to complete all the catechesis needed to be accepted into the assembly, to be permitted to undergo the rite of Holy Baptism, which was commonly done only at Easter. And during these forty days of Lent modeled on the forty days of Christ’s tempting in the desert about which we heard in the Gospel lesson, the catechumens underwent their most rigorous training and testing, with mortification of the flesh, denial of even the simplest pleasures, a severely restricted diet (a “fast” in the dietary sense). Only then could they be baptized.

This was a big deal because baptism was considered a sort of death. St. Paul puts it this way in the Letter to Romans (not in the portion we heard today, but in the Sixth Chapter in a passage we read on Easter morning): “Do you not know that all of us who have been baptized into Christ Jesus were baptized into his death?” (Rom. 6:3) The symbolism of Holy Baptism, especially when done in the traditional way by full immersion, is that the water represents the soil of the grave; we are “buried” as we go under the surface and as we come up out of it, we are resurrected: “If we have been united with him in a death like his, we will certainly be united with him in a resurrection like his. . . . If we have died with Christ, we believe that we will also live with him.” (6:6,8)

So Lent was a time for this baptismal preparation, and it was a time that reminded every member of the church of their own baptismal promises, of their own “death” to the world and their new, resurrected life in Christ, of the seriousness of what it meant (and means) to be a Christian.

It was also a time when those who, because of notorious sins, had been separated from the body of the faithful were reconciled by penitence and forgiveness, and restored to the fellowship of the Church.

There was no rite of private confession in the early church; that was created by the Irish monks in the 6th Century and eventually spread to the whole church after the 9th Century. Nor was there a general confession in the early liturgies such as we now have in the Anglican form of worship that we enjoy. No, in the early church when a member was guilty of some grave sin they had to confess it before the whole assembly, after which they would be excluded from communion and they would be given some penance, some way to make amends before they would be permitted to return to worship with the congregation.

Thereby, the whole congregation was put in mind of the message of pardon and absolution set forth in the Gospel of our Savior, and of the need which all Christians continually have to renew their repentance and faith.

Of course, the congregation would, as the admonition suggests, realize that not only was the repentant sinner in need of forgiveness; they all were — and we all are. You’ll remember the story of Jesus encountering the rabbis and villagers planning to stone the woman taken in adultery. “Let anyone among you who is without sin be the first to throw a stone at her,” he said. (John 8:7) And not one of them did so because they realized, as Lent calls us to realize, that we are all sinners and all stand in need of forgiveness.

I invite you, therefore, in the name of the Church, to the observance of a holy Lent, by self-examination and repentance; by prayer, fasting, and self-denial; and by reading and meditating on God’s holy Word.

So this closing invitation to “a holy Lent” just asks us to do a lot of things we hear about every Lent, doesn’t it? Every year someone like me gets up in front of the congregation in every parish and prattles on about things we should do for the next six weeks, which are really things we ought to do year-round, but this time of year we sort of focus on them. We know we’re supposed to “fast” – that means give something up, right?

When people ask me what I’m going to give up for Lent, I always answer, “Chocolate.” It’s easy for me to give that up – I don’t eat chocolate. I should give up . . . I don’t know . . . my Irish whiskey? Good wines? I know! I’ll give up Downton Abbey right after tonight’s episode (the Season 3 finale).

But really, the point of fasting and self-denial is not the “mortification of the flesh.” It isn’t making oneself miserable because we think we ought to join Jesus in his desert misery, his famished hunger as described in today’s gospel lesson. The point of giving something up is to make room in our lives for something else, or to pay over or pay forward that which we give up to the benefit of someone else, or to concentrate on something of spiritual benefit to ourselves.

In the Book of the Prophet Isaiah, God questions God’s people about fasting. “Such fasting as you do today will not make your voice heard on high,” writes the Prophet. Delivering God’s word, Isaiah tells us that God asks, “Is such the fast that I choose, a day to humble oneself? Is it to bow down the head like a bulrush, and to lie in sackcloth and ashes? Will you call this a fast, a day acceptable to the Lord?” (58:4-5) The answer to these questions is clearly, “No.” The Prophet continues:

Is not this the fast that I choose: to loose the bonds of injustice, to undo the thongs of the yoke, to let the oppressed go free, and to break every yoke? Is it not to share your bread with the hungry, and bring the homeless poor into your house; when you see the naked, to cover them, and not to hide yourself from your own kin? (58:6-7)

If I give up whiskey for Lent, the money I save not buying it should be given to World Vision International or to Episcopal Relief and Development or to our own Free Farmers’ Market food pantry. If I do give up Downton Abbey, the time I save should be given to study of Scripture, another of the admonitions of this Ash Wednesday exhortation.

The forty days of Lent are, symbolically, our time with Jesus in the desert, our time to emulate our Lord in his preparation for ministry, our time to face our temptations as he faced his. Note how he did so. Each time the devil would set something wonderful before him – food, or world power, or spiritual superiority – Jesus responded by quoting Scripture. Jesus was sustained, strengthened, and empowered by the words of the Law and the Prophets. How many of us could do that?

The truth is that I couldn’t! I’ve never been able to memorize chapter and verse. If you ask me, “Doesn’t the Bible say something about . . . . ?” my response will be to shrug my shoulders and say, “I don’t know. I’ll look that up.” Don’t get me wrong! I read Scripture all the time, every day in fact. I just don’t have the head to remember it all. That’s what concordances and computer search programs are for! I know what’s in there, I just don’t always know where it is. But just because someone may not have the knack to remember chapter-and-verse is no excuse not to study God’s Word. So I do, and I commend the practice to you, so that, as Paul wrote to the Romans, “The word [will be] near you, on your lips and in your heart.” We are all, as the collect for today confesses, assaulted by many temptations; through study and contemplation of the Bible, we can each find God mighty to save; we can each, like Jesus, be sustained and strengthened and empowered by Scripture.

And, to make a right beginning of repentance, and as a mark of our mortal nature, let us now kneel before the Lord, our maker and redeemer.

And then there is a rubric, a word of instruction, saying, “Silence is then kept for a time.” The rubric is not part of the Ash Wednesday exhortation, but those may be the most important words on the page.

When the exhortation and our tradition ask us to “give something up for Lent,” the purpose is to turn our attention from the distractions of the world around us. At the vestry’s retreat the past couple of days, our facilitator asked us to consider the difference between “doing” and “being”, to consider whether the job of the vestry is to “do things” or rather to “be something”. As part of a clergy study group, I’m currently reading a book entitled Beyond Busyness: Time Wisdom in Ministry. The author’s premise is that being “busy” is a bad thing, that when we are “busy” we are allowing a lot of small distractions take us away from the bigger, more important things one which we should use our time. “Busyness” results from concentrating too much on “doing” and too little on “being”.

Keeping silence for a time helps us turn our attention away from busy doing and toward productive being.

There is a lovely verse from the Psalms. (Don’t ask me which verse in which psalm! Remember, I just can’t recall that stuff.) The verse reads, “Be still, and know that I am God!” (46:10) In those catalogs like National Public Radio and Public Broadcasting send out from time to time, I’ve seen a carved stone plaque of that verse which repeats the verse several times, but in each reiteration leaves off a word or two:

Be still and know that I am God.

Be still and know that I am.

Be still and know.

Be still.

Be.

So I leave you with the rubric as, perhaps, the most important admonition of Lent: “Silence is kept for a time.” Be still and know that God is God. . . . . Be still and know that God is. . . . . Be still and know. . . . . Be still. . . . . Be.

Amen.

Could it get any simpler? “Look, here is Jesus.” The proclamation of the Good News, the invitation into personal relationship with our Incarnate God, the revelation of what it is to be truly human . . . whatever you want to call it (we’ll steer clear for the moment from the word “evangelism”), it can’t get any simpler than this: “Look, here he is.”

Could it get any simpler? “Look, here is Jesus.” The proclamation of the Good News, the invitation into personal relationship with our Incarnate God, the revelation of what it is to be truly human . . . whatever you want to call it (we’ll steer clear for the moment from the word “evangelism”), it can’t get any simpler than this: “Look, here he is.” Does it bother anyone else that as soon as Mrs. Simon’s mother is healed by Jesus she gets up from her sick bed and “begins to serve them”? That has always bothered me. I don’t know why it should. After all, if she’s healed (and one assumes that when Jesus healed someone they were really healed), then there’s no reason for her not to do what she would have done if she’d not been sick in the first place. But . . . it has bothered me. Why, I have thought, should this poor woman who’s been sick have to get out of bed and serve these men?

Does it bother anyone else that as soon as Mrs. Simon’s mother is healed by Jesus she gets up from her sick bed and “begins to serve them”? That has always bothered me. I don’t know why it should. After all, if she’s healed (and one assumes that when Jesus healed someone they were really healed), then there’s no reason for her not to do what she would have done if she’d not been sick in the first place. But . . . it has bothered me. Why, I have thought, should this poor woman who’s been sick have to get out of bed and serve these men? Jesus walking on the water has always struck me as a very funny story. “Funny” in the sense of “oddly out of place”, although it also has a certain Monty-Python-esque quality to it as well. The fact that it is reported in three of the Gospels – in the synoptic Gospels of Mark and Matthew and here in John – attests to its importance for the early church. John’s version of the story is the simplest, but it contains all the elements – a storm, rough seas, disciples’ fear. Like Mark, John leaves out Matthew’s addition of Peter trying to join Jesus on the surface of the lake.

Jesus walking on the water has always struck me as a very funny story. “Funny” in the sense of “oddly out of place”, although it also has a certain Monty-Python-esque quality to it as well. The fact that it is reported in three of the Gospels – in the synoptic Gospels of Mark and Matthew and here in John – attests to its importance for the early church. John’s version of the story is the simplest, but it contains all the elements – a storm, rough seas, disciples’ fear. Like Mark, John leaves out Matthew’s addition of Peter trying to join Jesus on the surface of the lake.  This is an old and familiar story, this tale of Christ healing the paralyzed man a the pool at Bethesda. We all know it well. The story continues with a confrontation between the man who has been and the Jewish religious authorities. This healing took place on the Sabbath. The confrontation is over whether it is proper for the man to carry his mat (i.e., perform work) on the Sabbath. The man’s defense is that the person who healed him told him to do so, although he doesn’t know (at the time) who the healer was. Later he learns it was Jesus and identifies him to the priests and scribes.

This is an old and familiar story, this tale of Christ healing the paralyzed man a the pool at Bethesda. We all know it well. The story continues with a confrontation between the man who has been and the Jewish religious authorities. This healing took place on the Sabbath. The confrontation is over whether it is proper for the man to carry his mat (i.e., perform work) on the Sabbath. The man’s defense is that the person who healed him told him to do so, although he doesn’t know (at the time) who the healer was. Later he learns it was Jesus and identifies him to the priests and scribes. “No matter how big and bad you are . . . when a two-year-old hands you a toy telephone, you answer it.” That piece of wisdom showed up on my Facebook newsfeed recently and I will return to it in a moment, but first I want to share some more Christmas poetry with you.

“No matter how big and bad you are . . . when a two-year-old hands you a toy telephone, you answer it.” That piece of wisdom showed up on my Facebook newsfeed recently and I will return to it in a moment, but first I want to share some more Christmas poetry with you. On the third day of Christmas the church calendar directs our attention to St. John the Evangelist and, again, the Daily Office lectionary falls in line. John is the gospeller whose wonderful prologue serves as the Gospel lesson at the Eucharist on Christmas Day (1:1-14) and on the first Sunday after Christmas (1:1-18). It is for me a much more meaningful Gospel of the Incarnation than Luke’s sweet story of innkeepers, shepherds, angels, and the virgin birth: “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God.” (v. 1)

On the third day of Christmas the church calendar directs our attention to St. John the Evangelist and, again, the Daily Office lectionary falls in line. John is the gospeller whose wonderful prologue serves as the Gospel lesson at the Eucharist on Christmas Day (1:1-14) and on the first Sunday after Christmas (1:1-18). It is for me a much more meaningful Gospel of the Incarnation than Luke’s sweet story of innkeepers, shepherds, angels, and the virgin birth: “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God.” (v. 1)