====================

A homily offered by the Rev. Dr. C. Eric Funston on the First Sunday of Advent, November 27, 2016, to the people of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Medina, Ohio, where Fr. Funston is rector.

(The lessons for the day are from the Revised Common Lectionary for Advent 1 in Year A: Isaiah 2:1-5; Psalm 122; Romans 13:11-14; and St. Matthew 24:36-44. These lessons can be read at The Lectionary Page.)

====================

“Two will be in the field; one will be taken and one will be left. Two women will be grinding meal together; one will be taken and one will be left. Keep awake therefore, for you do not know on what day your Lord is coming.” (Matt 24:40-42) You probably have friends who have told you these verses from Matthew’s Gospel describe something called “the Rapture.” You may have read the Left Behind books or seen the movies. So you may think you have a handle on what these verses mean and why they are offered to us as we begin our Advent preparation to celebrate the anniversary of Christ’s Incarnation and to look forward to his return, his “Second Coming.”

“Two will be in the field; one will be taken and one will be left. Two women will be grinding meal together; one will be taken and one will be left. Keep awake therefore, for you do not know on what day your Lord is coming.” (Matt 24:40-42) You probably have friends who have told you these verses from Matthew’s Gospel describe something called “the Rapture.” You may have read the Left Behind books or seen the movies. So you may think you have a handle on what these verses mean and why they are offered to us as we begin our Advent preparation to celebrate the anniversary of Christ’s Incarnation and to look forward to his return, his “Second Coming.”

Well… just hold that thought for a moment and let’s explore the first reading before we get back to it.

This is such a great passage from the Prophet Isaiah that we have this morning. It’s got those wonderful verses that are carved into the wall of the broad plaza across the street from the United Nations building in New York City:

They shall beat their swords into ploughshares,

and their spears into pruning-hooks;

nation shall not lift up sword against nation,

neither shall they learn war any more. (Isa 2:4, NRSV)

It’s got all that wonderful imagery of the nations of the world streaming toward the Temple of the Lord in Jerusalem, at peace with one another. It’s a wonderful, wonderful vision.

We keep waiting for it, don’t we?

Isaiah saw this vision during the reign of King Uzziah of Judah about 750 years before Jesus’ time. Isaiah promulgated what is known as “Zion theology,” a religious understanding of Jerusalem as the center of the world and the Temple as the center of Jerusalem. The Lord will come to it and its mount, Holy Zion, will be the most prominent mountain. The nations will all come to Jerusalem to learn divine teaching. Yahweh, enthroned in the Temple, will mediate and end all international conflict. The waging of war will cease.

Of course, none of that has ever happened, but for nearly eight centuries after Isaiah the son of Amoz this was the belief and hope of Israel, of all Jews. The realities of this text exist in the realms of promise, hope, and faith.

Or at least they did until about forty years after Jesus’ death and resurrection.

Here’s a little First Century history lesson:

Jesus was born sometime around the year we might think of as “Zero” – in truth, we think he was born about the year now designated 4 B.C. (The calendar designations we use were developed by a man named Dionysus Exiguus – Dennis the Short – around the year 525 A.D. Dennis made a couple of miscalculations and so our calendar is just a bit off; it really doesn’t start with the birth of Jesus.) He lived to about his mid-thirties; the most popular dating of the crucifixion is April 3 of the year 33 A.D.

The Gospels were written several years after Jesus’ Ascension. Folks apparently thought it would be a good idea to get things written down because the original followers of Jesus were dying off. So Mark’s gospel was compiled a few years before 70 A.D., perhaps in the mid-60s. Matthew’s gospel is believed to have come next, about 80 A.D., perhaps as late as 90 A.D. Luke wrote his gospel and the Book of Acts at about the same time. John’s gospel comes along about the year 100 A.D.

These dates are important because of what happened in Jerusalem in 70 A.D.

Around the year 64 A.D. the Jews of Jerusalem rebelled against the then-ruling Roman Procurator, a man named Gessius Florius, who had tried to take the Temple treasury for his own use. They succeeded in expelling Florius from the city, but only after nearly 4,000 Jews had been killed. Then they got into a battle amongst themselves. There was essentially a civil war between the forces of Herod Agrippa, the grandson of Herod the Great, who claimed to be king, and Eliezer ben-Hananiah, who was the high priest.

This division between the Jews allowed the Roman Procurator of Syria Cestius Gallius to lay siege to the city for four years between 66 and 70 A.D. and basically starve the Jews. In the late summer of 70 A.D. the Roman general Titus Flavius successfully breached the city walls and destroyed the city and the Temple. The contemporary Jewish historian Joseph ben Matityahu reported that more than a million Jews were killed.

That is when the Zion theology of Isaiah took a nearly fatal blow. There was no longer a Temple to which (as the Psalmist put it)

the tribes [could] go up,

the tribes of the Lord,

the assembly of Israel,

to praise the Name of the Lord. (Ps 122:4, BCP 1979 Version)

This was also the background, the context within which Matthew’s and Luke’s gospels were written. When the authors set about to record the story of Jesus, they look back to view him through the smoke of burning Jerusalem, across the rubble of the destroyed Temple.

Thus, they remembered things that Jesus had said about the Temple’s destruction. They remembered things that Jesus had said about his own probable death. They remembered and interpreted and wrote about many things in light of what was happening and had happened in the world around them. Of course they did! They were just as human as you and me, and the way they saw things and understood things and reported things was influenced by their experiences.

“The impact of this catastrophe cannot be overestimated. The loss of the war was itself devastating. The loss of the city of Jerusalem, the symbolic unifier of the Jewish people and the physical link to the memories that make Jews distinctively Jewish, tying them together all the way back to David, who ruled from this city, this loss shook the people deeply.” (Prof. Richard W. Swanson) Including the followers of Jesus, who at that time still thought of themselves as Jews.

Which brings us back to those verses from today’s gospel reading . . . that much cited and much misinterpreted text! When they remembered Jesus saying, “Then two will be in the field; one will be taken and one will be left. Two women will be grinding meal together; one will be taken and one will be left” (Matt 24:40-41), the evangelists didn’t think he was talking about something that would happen in some future when he would return. They believed, probably correctly, that he was talking about something that had already happened to them and to their families and to their country. They had lived through a devastating and now inescapable loss. As a result of the Roman destruction of Jerusalem and the Temple, which they had 800 years of regarding as the center of the universe, “every extended family [had] lost many members.” (Swanson)

In Luke’s version of this story, by the way, the disciples ask a follow-up question: Jesus says, “I tell you, on that night there will be two in one bed; one will be taken and the other left. There will be two women grinding meal together; one will be taken and the other left.” (Lk 17:34-35) Then his followers ask, “Where, Lord?” and Jesus them to look for the ones taken “Where the corpse is,” where “the vultures will gather.” The authors of the gospels were not looking forward to this happening; they had already been through it. (See Benjamin Corey)

It wasn’t until a crazy Irish Anglican priest named John Darby took these verses out of context and mashed it together with something Paul wrote to the Thessalonians about being “caught up in the clouds together with [the risen dead] to meet the Lord in the air” (1 Thes 4:17), and stirred it all together with some crazy imagery from the Book of Revelation, that we get the notion of a “rapture.” That “pointless [and] weird theology has . . . produced some strange bumper stickers (In case of Rapture this car will be driverless, etc.), and bad movies (you know which ones), [but] it is not what these words are about.” (Swanson)

These words are about hope even in the worst possible of circumstances. As Professor Arland Hultgren of Luther Seminary says:

The message of Christ’s return is not meant to frighten us. It is to give us hope. ~ The Christ who is to come is the Christ who once lived among us on earth, and who is known in the gospel story as the friend and healer of those in need. Moreover, living in hope, expecting Christ’s return, is integral to the Christian faith, for by it we insist that there is more to the human story and God’s own story than that which has been experienced already. (Hultgren)

There is another prophet whose words convey this message, the Prophet Habakkuk who shouted his intent to praise the Lord even when everything had gone bad. He wrote:

Though the fig tree does not blossom, and no fruit is on the vines; though the produce of the olive fails, and the fields yield no food; though the flock is cut off from the fold, and there is no herd in the stalls, yet I will rejoice in the Lord; I will exult in the God of my salvation. God, the Lord, is my strength; he makes my feet like the feet of a deer, and makes me tread upon the heights. (Hab 3:17-19a)

This is the hope of Advent, the hope that lets us believe, indeed lets us know with certainty that although Jerusalem may be destroyed, although the Temple may be in ruins, although war may rage around us, still there will be a time when

they shall beat their swords into ploughshares,

and their spears into pruning-hooks;

nation shall not lift up sword against nation,

neither shall they learn war any more. (Isa 2:4)

“Therefore you also must be ready, for the Son of Man [who will usher in that time of peace] is coming at an unexpected hour.” Amen.

Note: The illustration is “Swords into Plowshares” by Lee Oscar Lawrie at the International Building, Rockefeller Center, NYC, NY.

====================

Father Funston is the rector of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Medina, Ohio.

It’s the last Sunday of the Christian year, sort of a New Year’s Eve for the church. We call it “the Feast of Christ the King” and we celebrate it by remembering his enthronement. As Pope Francis reminded the faithful in his Palm Sunday homily a few years ago, “It is precisely here that his kingship shines forth in godly fashion: his royal throne is the wood of the Cross!” (

It’s the last Sunday of the Christian year, sort of a New Year’s Eve for the church. We call it “the Feast of Christ the King” and we celebrate it by remembering his enthronement. As Pope Francis reminded the faithful in his Palm Sunday homily a few years ago, “It is precisely here that his kingship shines forth in godly fashion: his royal throne is the wood of the Cross!” ( Good evening! For those who don’t know me, I am Eric Funston, a priest of the Episcopal Church and rector of St. Paul’s Parish in Medina, Ohio. For those of you who don’t know why I’m preaching here tonight . . . I wish I could tell you! Usually these ordination or installation homily gigs go to someone with whom the new clergy person has had a, shall we say, formative relationship: a former pastor, a seminary professor or a ministry supervisor, an elder minister under whom the new pastor served a curacy, someone responsible for the priestly formation of the new rector. But that doesn’t describe me . . . I am not responsible for George Baum ~ and that is very probably a good thing!

Good evening! For those who don’t know me, I am Eric Funston, a priest of the Episcopal Church and rector of St. Paul’s Parish in Medina, Ohio. For those of you who don’t know why I’m preaching here tonight . . . I wish I could tell you! Usually these ordination or installation homily gigs go to someone with whom the new clergy person has had a, shall we say, formative relationship: a former pastor, a seminary professor or a ministry supervisor, an elder minister under whom the new pastor served a curacy, someone responsible for the priestly formation of the new rector. But that doesn’t describe me . . . I am not responsible for George Baum ~ and that is very probably a good thing!  On the day after the general election, a Presbyterian clergyman in Iowa, a married gay man, found a computer-printed note tucked under his car’s windshield wiper addressed to “Father Homo.” The text of the note began with the question “How does it feel to have Trump as your president?” and was both belittling and threatening. The same day a softball dugout in Island Park in Wellsville, New York, was defaced with graffiti reading “Make America White Again,” accompanied by a large swastika. The next day, students at nearby Canisius College, a Jesuit institution, found a black baby doll with a noose tied around its neck in the freshman dormitory elevator, and students at Wellesley College in Massachusetts witnessed two young white men drive a truck through their campus flying a Trump campaign banner, yelling “Make American Great Again,” and spitting on African-American young women.

On the day after the general election, a Presbyterian clergyman in Iowa, a married gay man, found a computer-printed note tucked under his car’s windshield wiper addressed to “Father Homo.” The text of the note began with the question “How does it feel to have Trump as your president?” and was both belittling and threatening. The same day a softball dugout in Island Park in Wellsville, New York, was defaced with graffiti reading “Make America White Again,” accompanied by a large swastika. The next day, students at nearby Canisius College, a Jesuit institution, found a black baby doll with a noose tied around its neck in the freshman dormitory elevator, and students at Wellesley College in Massachusetts witnessed two young white men drive a truck through their campus flying a Trump campaign banner, yelling “Make American Great Again,” and spitting on African-American young women. Tuesday was the Feast of All Saints (which we are commemorating today, as is permitted by tradition, by translating the feast to the following Sunday). Traditionally, All Saints Day (or All Saints Sunday) commemorates the departed members of the Christian church who are believed to have attained heaven (it is not limited to those officially canonized by a church hierarchy).

Tuesday was the Feast of All Saints (which we are commemorating today, as is permitted by tradition, by translating the feast to the following Sunday). Traditionally, All Saints Day (or All Saints Sunday) commemorates the departed members of the Christian church who are believed to have attained heaven (it is not limited to those officially canonized by a church hierarchy).  For the past couple of weeks in the Daily Office lectionary and today in the Sunday lectionary we are reading from the Wisdom of Yeshua ben Sira, some times called Sirach, sometimes called Ecclesiasticus, one of the books of the Apocrypha, those books recognized by the Roman and Eastern Orthodox churches as canonical, but rejected by Protestants. Anglicans steer a middle course and accept them for moral teaching, but not as the basis for religious doctrine. The text is a late example of what is called “wisdom literature,” instruction in ethics and proper social behavior for young men, especially those likely to take a role in governance.

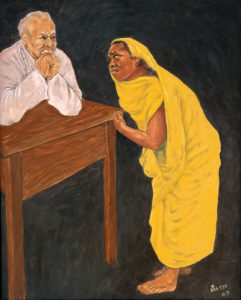

For the past couple of weeks in the Daily Office lectionary and today in the Sunday lectionary we are reading from the Wisdom of Yeshua ben Sira, some times called Sirach, sometimes called Ecclesiasticus, one of the books of the Apocrypha, those books recognized by the Roman and Eastern Orthodox churches as canonical, but rejected by Protestants. Anglicans steer a middle course and accept them for moral teaching, but not as the basis for religious doctrine. The text is a late example of what is called “wisdom literature,” instruction in ethics and proper social behavior for young men, especially those likely to take a role in governance. The story of the “unjust judge” has to be one of the most confusing of Jesus’ parables related in any of the Gospels. In every bible study group I have ever been a part of someone will want to know how the “unjust judge” could possibly represent God . . . .

The story of the “unjust judge” has to be one of the most confusing of Jesus’ parables related in any of the Gospels. In every bible study group I have ever been a part of someone will want to know how the “unjust judge” could possibly represent God . . . .  For ten months, since the First Sunday of Advent 2015, we have been in Lectionary Year C, during which we’ve been following texts from the Gospel according to Luke. Luke’s Gospel , after telling of his birth and infancy, sets out Jesus’ original mission statement, which he adopted from the Prophet Isaiah and proclaimed in his hometown synagogue:

For ten months, since the First Sunday of Advent 2015, we have been in Lectionary Year C, during which we’ve been following texts from the Gospel according to Luke. Luke’s Gospel , after telling of his birth and infancy, sets out Jesus’ original mission statement, which he adopted from the Prophet Isaiah and proclaimed in his hometown synagogue:![Dives and Lazarus. Psalter (Munich Golden Psalter). England [Gloucester?], 1st quarter of the 13th century.](http://thefunstons.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/Lazarus-and-Dives-300x264.jpg) We could, I suppose, spiritualize the story of Lazarus and the rich man. We could, but if we did we would be twisting it out of shape. This is not a spiritual story. This is a bare-knuckled street-brawl of a story about wealth, about money and possessions, about someone who had plenty and about someone who had none. If we are going to honor the biblical text, we cannot spiritualize this tale; we have to deal with it as it is given us, as a story about money.

We could, I suppose, spiritualize the story of Lazarus and the rich man. We could, but if we did we would be twisting it out of shape. This is not a spiritual story. This is a bare-knuckled street-brawl of a story about wealth, about money and possessions, about someone who had plenty and about someone who had none. If we are going to honor the biblical text, we cannot spiritualize this tale; we have to deal with it as it is given us, as a story about money. I’d like you all to take your Prayer Books in hand and turn with me to page 855 which is way in the back of the book in the section called The Catechism or Outline of the Faith. At the top of the page are three questions about the mission of the church and the answers to those questions that we as Episcopalians teach. I’m going to read the questions; I’d like you to read the answers:

I’d like you all to take your Prayer Books in hand and turn with me to page 855 which is way in the back of the book in the section called The Catechism or Outline of the Faith. At the top of the page are three questions about the mission of the church and the answers to those questions that we as Episcopalians teach. I’m going to read the questions; I’d like you to read the answers: