Matthew wrote:

When Jesus came to the other side, to the country of the Gadarenes, two demoniacs coming out of the tombs met him. They were so fierce that no one could pass that way.

(From the Daily Office Lectionary – Matthew 8:28 – May 23, 2012)

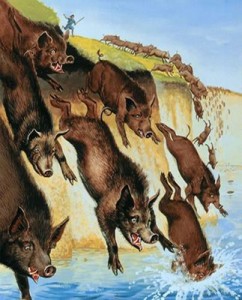

This is the beginning of familiar story. The demons challenge Jesus, “What have you to do with us?” and he, in turn, banishes them into a herd of swine, which then rush into the Sea of Galilee and drown. The swineherds run into the nearby town and tell what happened. The townspeople come out and, being afraid, beg Jesus to leave. Of course, the demoniacs are cured but we don’t know anything further about them. Matthew’s version of the story puzzles me. Mark and Luke also tell the tale and, if scholars are correct, it’s likely that Luke and Matthew got it from Mark who wrote his gospel first. (Compare Mark 5 and Luke 8.) ~ Here’s the first thing that puzzles me – Matthew slightly changes the location. Mark and Luke say this happened in the country of Gerasenes; Matthew, in the country of the Gadarenes. Now I know from my bible studies that these towns, Gadara and Gerasa, are close to one another and neither is actually on the Galilean lake. Both are Gentile towns near the eastern shore of the lake. The town in that area on the lake was Hippos. Why did Matthew choose to put this event in this slightly different location? I don’t know. And, so far, as I know there is no scholarship to answer that question. It’s just, as Yul Brynners king of Siam would say, a puzzlement. ~ The second puzzlement is why Matthew doubles the number of demoniacs. In Marks original tale and Luke’s repetition of it, there is a single possessed man. Matthew says there were two. In all other respects than these two details, the stories are the same. Why does Matthew say there were two possessed persons? Does that make the healing twice the miracle as it is in Mark’s version? I don’t think so. It’s just as frightening to the townspeople – whether Jesus cures one man or two, they still beg him to leave. ~ I have no answers to these puzzlements. I don’t even know if these minor changes of detail have any significance. Probably they don’t. But these little details are among the things about scripture study and contemplation that sometimes grab my attention and make me lay awake at night wondering, “Why two? Why two?” ~ It’s a puzzlement!

This is the beginning of familiar story. The demons challenge Jesus, “What have you to do with us?” and he, in turn, banishes them into a herd of swine, which then rush into the Sea of Galilee and drown. The swineherds run into the nearby town and tell what happened. The townspeople come out and, being afraid, beg Jesus to leave. Of course, the demoniacs are cured but we don’t know anything further about them. Matthew’s version of the story puzzles me. Mark and Luke also tell the tale and, if scholars are correct, it’s likely that Luke and Matthew got it from Mark who wrote his gospel first. (Compare Mark 5 and Luke 8.) ~ Here’s the first thing that puzzles me – Matthew slightly changes the location. Mark and Luke say this happened in the country of Gerasenes; Matthew, in the country of the Gadarenes. Now I know from my bible studies that these towns, Gadara and Gerasa, are close to one another and neither is actually on the Galilean lake. Both are Gentile towns near the eastern shore of the lake. The town in that area on the lake was Hippos. Why did Matthew choose to put this event in this slightly different location? I don’t know. And, so far, as I know there is no scholarship to answer that question. It’s just, as Yul Brynners king of Siam would say, a puzzlement. ~ The second puzzlement is why Matthew doubles the number of demoniacs. In Marks original tale and Luke’s repetition of it, there is a single possessed man. Matthew says there were two. In all other respects than these two details, the stories are the same. Why does Matthew say there were two possessed persons? Does that make the healing twice the miracle as it is in Mark’s version? I don’t think so. It’s just as frightening to the townspeople – whether Jesus cures one man or two, they still beg him to leave. ~ I have no answers to these puzzlements. I don’t even know if these minor changes of detail have any significance. Probably they don’t. But these little details are among the things about scripture study and contemplation that sometimes grab my attention and make me lay awake at night wondering, “Why two? Why two?” ~ It’s a puzzlement!

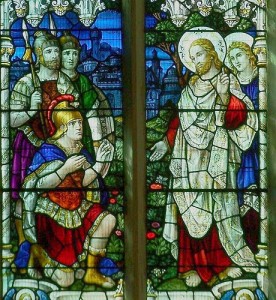

The words of the centurion are the root of a prayer spoken by many before receiving Holy Communion: “Lord, I am not worthy to receive you, but only say the word and I shall be healed.” As an Anglo-Catholic Episcopalian, recitation of this prayer used to be a part of my personal practice. But I have ceased to say it because I became uncomfortable about the change in emphasis from the biblical text to the liturgical text. A statement of faith in Christ’s power to heal another has been turned into a purely personal (and one is tempted to say “selfish”) prayer. ~ Paragraph 1386 of the catechism of the Roman Catholic Church explains the rational of the prayer: “Before so great a sacrament, the faithful can only echo humbly and with ardent faith the words of the Centurion: ‘Domine, non sum dignus ut intres sub tectum meum, sed tantum dic verbo, et sanabitur anima mea’ (‘Lord, I am not worthy that you should enter under my roof, but only say the word and my soul will be healed.’)” That’s great, except the quotation from the Centurion is inaccurate! In the Vulgate, the verse reads, “Tantum dic verbo et sanabitur puer meus.” (“Only say the word and my servant [or ‘child’] shall be healed.”) I am troubled reciting a prayer based on a misquotation of scripture. ~ The centurion in the story is about as far from self-centered as one can be. He seeks Jesus’ help not for himself but for his servant. He is unwilling for Jesus to be inconvenienced. It is in that spirit that he speaks these words, explaining that as a military officer he simply gives orders and things are done, so he has faith that One with the power of healing can simply do the same. It is for his selflessness that Jesus’ praises him and his faith. It seems somehow wrong to recite a prayer which turns that on its head! ~ I recall reading a few years ago about a medical brain-function study which demonstrated that selflessness is psychologically healthy and is the neuropsychological foundation of spiritual experience. Selfishness, on the other hand, is unhealthy: other scientific studies have demonstrated that it is impossible for a completely selfish individual to either survive or have a biological future. So I am unwilling to utter a prayer which turns a selfless intercession on behalf of another into a self-centered (one is tempted to say “selfish”) petition. “Lord, I am unworthy to receive you” … let’s just leave it at that.

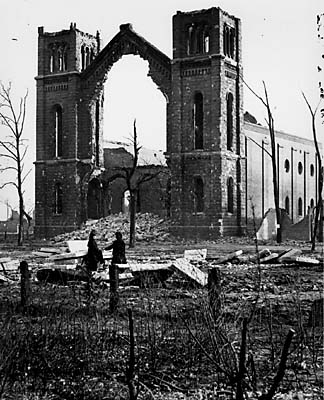

The words of the centurion are the root of a prayer spoken by many before receiving Holy Communion: “Lord, I am not worthy to receive you, but only say the word and I shall be healed.” As an Anglo-Catholic Episcopalian, recitation of this prayer used to be a part of my personal practice. But I have ceased to say it because I became uncomfortable about the change in emphasis from the biblical text to the liturgical text. A statement of faith in Christ’s power to heal another has been turned into a purely personal (and one is tempted to say “selfish”) prayer. ~ Paragraph 1386 of the catechism of the Roman Catholic Church explains the rational of the prayer: “Before so great a sacrament, the faithful can only echo humbly and with ardent faith the words of the Centurion: ‘Domine, non sum dignus ut intres sub tectum meum, sed tantum dic verbo, et sanabitur anima mea’ (‘Lord, I am not worthy that you should enter under my roof, but only say the word and my soul will be healed.’)” That’s great, except the quotation from the Centurion is inaccurate! In the Vulgate, the verse reads, “Tantum dic verbo et sanabitur puer meus.” (“Only say the word and my servant [or ‘child’] shall be healed.”) I am troubled reciting a prayer based on a misquotation of scripture. ~ The centurion in the story is about as far from self-centered as one can be. He seeks Jesus’ help not for himself but for his servant. He is unwilling for Jesus to be inconvenienced. It is in that spirit that he speaks these words, explaining that as a military officer he simply gives orders and things are done, so he has faith that One with the power of healing can simply do the same. It is for his selflessness that Jesus’ praises him and his faith. It seems somehow wrong to recite a prayer which turns that on its head! ~ I recall reading a few years ago about a medical brain-function study which demonstrated that selflessness is psychologically healthy and is the neuropsychological foundation of spiritual experience. Selfishness, on the other hand, is unhealthy: other scientific studies have demonstrated that it is impossible for a completely selfish individual to either survive or have a biological future. So I am unwilling to utter a prayer which turns a selfless intercession on behalf of another into a self-centered (one is tempted to say “selfish”) petition. “Lord, I am unworthy to receive you” … let’s just leave it at that. Two things happened yesterday. First, I had a conversation with my son (who is also a priest) about the future of parish ministry. Suffice it to say that we both have misgivings and considerable trepidation about that; I, for one, don’t see much future for parish ministry unless the church makes some radical changes – too many are needed to discuss in detail in a short morning meditation like this one. ~ Second, as a member of a committee charged with approving assistance grants to local congregations, I was asked yet again to approve a grant to fix a roof. The roof in question is for a parish which is not supporting itself through the giving of its membership. It seems to survive on grants and the largesse of a single, now-dead member who established a trust for its benefit; without those funding sources, it could not sustain its budget. I commented to my fellow committee members: “I wonder why we keep pumping money into maintaining buildings for marginal congregations. We ought to be investing in health and this doesn’t feel like we’re doing that.” ~ Both of those conversations came to mind when I read this gospel lesson today . . . as did an on-line (Facebook) tête-à-tête with a priest in England about car insurance rates, capitalism, and the plight of the poor in which we both suggested that force might be the only way to change the world economic system. I suggested to my colleague that our agreement on that point “means that we are acknowledging the church’s failure to accomplish its mission.” ~ And then another colleague, a younger preacher active in the “emergent church” movement reminded me of this observation from Episcopal priest and author Robert Farrar Capon: “The church can’t rise because it refuses to drop dead. The fact that it’s dying is of no use whatsoever: dying is simply the world’s most uncomfortable way of remaining alive. If you are to be raised from the dead, the only thing that can make you a candidate is to go all the way into death. Death, not life, is God’s recipe for fixing up the world.” (The Astonished Heart: Reclaiming the Good News from the Lost-and-Found of Church History, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 1996) ~ The rains, floods, and winds are beating against the house that is the church, especially against the houses that are the parishes of the mainstream denominations. We have got to change in radical ways. We have got to stop listening to the world and start, again, listening to Jesus! Radical, by the way, is derived from the Latin radix meaning “root”; the change we need to make is a return to our roots, to Jesus and the apostles, to early Christian understandings of what means to be church. We have to change or the church will, indeed, fall. I think Capon is right – the church as it has become has to drop dead in order to rise again, or it will fall – and if it simply falls, its fall will be great and it will not get up.

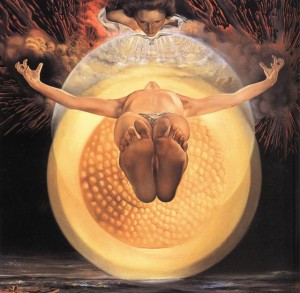

Two things happened yesterday. First, I had a conversation with my son (who is also a priest) about the future of parish ministry. Suffice it to say that we both have misgivings and considerable trepidation about that; I, for one, don’t see much future for parish ministry unless the church makes some radical changes – too many are needed to discuss in detail in a short morning meditation like this one. ~ Second, as a member of a committee charged with approving assistance grants to local congregations, I was asked yet again to approve a grant to fix a roof. The roof in question is for a parish which is not supporting itself through the giving of its membership. It seems to survive on grants and the largesse of a single, now-dead member who established a trust for its benefit; without those funding sources, it could not sustain its budget. I commented to my fellow committee members: “I wonder why we keep pumping money into maintaining buildings for marginal congregations. We ought to be investing in health and this doesn’t feel like we’re doing that.” ~ Both of those conversations came to mind when I read this gospel lesson today . . . as did an on-line (Facebook) tête-à-tête with a priest in England about car insurance rates, capitalism, and the plight of the poor in which we both suggested that force might be the only way to change the world economic system. I suggested to my colleague that our agreement on that point “means that we are acknowledging the church’s failure to accomplish its mission.” ~ And then another colleague, a younger preacher active in the “emergent church” movement reminded me of this observation from Episcopal priest and author Robert Farrar Capon: “The church can’t rise because it refuses to drop dead. The fact that it’s dying is of no use whatsoever: dying is simply the world’s most uncomfortable way of remaining alive. If you are to be raised from the dead, the only thing that can make you a candidate is to go all the way into death. Death, not life, is God’s recipe for fixing up the world.” (The Astonished Heart: Reclaiming the Good News from the Lost-and-Found of Church History, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 1996) ~ The rains, floods, and winds are beating against the house that is the church, especially against the houses that are the parishes of the mainstream denominations. We have got to change in radical ways. We have got to stop listening to the world and start, again, listening to Jesus! Radical, by the way, is derived from the Latin radix meaning “root”; the change we need to make is a return to our roots, to Jesus and the apostles, to early Christian understandings of what means to be church. We have to change or the church will, indeed, fall. I think Capon is right – the church as it has become has to drop dead in order to rise again, or it will fall – and if it simply falls, its fall will be great and it will not get up.  Today is the Feast of the Ascension. Today we remember that, forty days after his resurrection, Jesus ascended into heaven, disappearing from his disciples’ sight into the clouds. Luke tells us in the Book of Acts that the disciples stood there gazing up towards heaven, and that two men, presumably angels, appeared and asked “Why do you stand looking up towards heaven? This Jesus, who has been taken up from you into heaven, will come in the same way as you saw him go into heaven.” (Acts 1:11) So we have two biblical promises: “I’m still with you” and “He’s not with you but he’ll be back.” The Christian paradox illustrated in the readings for a single day. ~ For me the meaning of the Ascension is summarized in the petition of one of the collects for the day in the American Book of Common Prayer (1979): that “we may also in heart and mind there ascend, and with him continually dwell” – or as Jesus put it in John’s gospel “that where I am, there you may be also.” (John 14:3) I don’t understand that as a future conditional promise but rather as a present permissive reality. Christ’s ascension allows us to be in God’s presence, now . . . no matter what our circumstance may be. It’s a matter of us recognizing that presence in the present, which we so often fail to do because we think of it as a future reward for some good behavior or something on our part when, in reality, it has nothing to do with our behavior or our goodness at all. The apparent paradox of the two biblical promises accurately reflects our confusion.

Today is the Feast of the Ascension. Today we remember that, forty days after his resurrection, Jesus ascended into heaven, disappearing from his disciples’ sight into the clouds. Luke tells us in the Book of Acts that the disciples stood there gazing up towards heaven, and that two men, presumably angels, appeared and asked “Why do you stand looking up towards heaven? This Jesus, who has been taken up from you into heaven, will come in the same way as you saw him go into heaven.” (Acts 1:11) So we have two biblical promises: “I’m still with you” and “He’s not with you but he’ll be back.” The Christian paradox illustrated in the readings for a single day. ~ For me the meaning of the Ascension is summarized in the petition of one of the collects for the day in the American Book of Common Prayer (1979): that “we may also in heart and mind there ascend, and with him continually dwell” – or as Jesus put it in John’s gospel “that where I am, there you may be also.” (John 14:3) I don’t understand that as a future conditional promise but rather as a present permissive reality. Christ’s ascension allows us to be in God’s presence, now . . . no matter what our circumstance may be. It’s a matter of us recognizing that presence in the present, which we so often fail to do because we think of it as a future reward for some good behavior or something on our part when, in reality, it has nothing to do with our behavior or our goodness at all. The apparent paradox of the two biblical promises accurately reflects our confusion.  This conversation troubles me. It falls at the end of a lengthy debate between Jesus and a group of biblical scholars composed of both Sadducees and Pharisees (two groups which seldom, if ever, agreed). They have challenged Jesus with three questions: the legality of paying taxes to Caesar; the status of a many-times married woman after the resurrection of the dead (whose wife will she be?); and the greatest of the commandments. Jesus has answered those questions and now asks them one of his own. It’s a trick question. It silences his critics and none of them ever again asks him a question. ~ That’s what troubles me. I don’t follow Jesus because he has the gift of witty repartee or because he has cut-and-dried answers to life’s questions or because he is a viciously effective debater who subdues his opponents. In fact, I follow Jesus for quite opposite reasons. I follow Jesus because in his footsteps I find pathways to contemplate and explore the questions of life to which there are often no solid answers. I follow Jesus because I find responses to my questions which invite and encourage further exploration, not answers which end and cut off discussion. ~ Was Jesus satisfied with the Pharisees response? Was he pleased that they sat mute and did not dare to ask a follow-up question? Matthew doesn’t tell us (nor does Mark, who tells the same story in a different fashion). But after this exchange, Jesus turns to the crowd and says to them about “the scribes and the Pharisees”, “Do not do what they do.” According to Matthew, Jesus apparently is referring to a lot of picky and burdensome ritual practices which the Pharisees heap onto others’ shoulders without lifting a finger to assist. But I wonder if he might not also be saying, “Don’t stop asking questions. Don’t stop exploring life’s issues. Don’t stop talking about God and the Messiah. Even if you don’t understand, maybe especially if you don’t understand, don’t sit there mute!” ~ On the Second Sunday of Easter the Eucharistic lectionary had us consider the story of “Doubting Thomas” (as it does every year). In my parish that was also “Children’s Sunday” when, instead of a formal recitation of the gospel and a learned sermon, the gospel is told to our children in story-book fashion with a discussion at their level of what it means. I suggested to them that it is very important to note that Jesus did not criticize Thomas for asking questions and that we should understand that to be an encouragement to ask questions of our own, and never stop doing so. So, yeah … I think Jesus may have been doing the same thing here. I think he may have been very disappointed in the Pharisees and Sadducees who did not “dare to ask him any more questions.” Don’t stop asking questions!

This conversation troubles me. It falls at the end of a lengthy debate between Jesus and a group of biblical scholars composed of both Sadducees and Pharisees (two groups which seldom, if ever, agreed). They have challenged Jesus with three questions: the legality of paying taxes to Caesar; the status of a many-times married woman after the resurrection of the dead (whose wife will she be?); and the greatest of the commandments. Jesus has answered those questions and now asks them one of his own. It’s a trick question. It silences his critics and none of them ever again asks him a question. ~ That’s what troubles me. I don’t follow Jesus because he has the gift of witty repartee or because he has cut-and-dried answers to life’s questions or because he is a viciously effective debater who subdues his opponents. In fact, I follow Jesus for quite opposite reasons. I follow Jesus because in his footsteps I find pathways to contemplate and explore the questions of life to which there are often no solid answers. I follow Jesus because I find responses to my questions which invite and encourage further exploration, not answers which end and cut off discussion. ~ Was Jesus satisfied with the Pharisees response? Was he pleased that they sat mute and did not dare to ask a follow-up question? Matthew doesn’t tell us (nor does Mark, who tells the same story in a different fashion). But after this exchange, Jesus turns to the crowd and says to them about “the scribes and the Pharisees”, “Do not do what they do.” According to Matthew, Jesus apparently is referring to a lot of picky and burdensome ritual practices which the Pharisees heap onto others’ shoulders without lifting a finger to assist. But I wonder if he might not also be saying, “Don’t stop asking questions. Don’t stop exploring life’s issues. Don’t stop talking about God and the Messiah. Even if you don’t understand, maybe especially if you don’t understand, don’t sit there mute!” ~ On the Second Sunday of Easter the Eucharistic lectionary had us consider the story of “Doubting Thomas” (as it does every year). In my parish that was also “Children’s Sunday” when, instead of a formal recitation of the gospel and a learned sermon, the gospel is told to our children in story-book fashion with a discussion at their level of what it means. I suggested to them that it is very important to note that Jesus did not criticize Thomas for asking questions and that we should understand that to be an encouragement to ask questions of our own, and never stop doing so. So, yeah … I think Jesus may have been doing the same thing here. I think he may have been very disappointed in the Pharisees and Sadducees who did not “dare to ask him any more questions.” Don’t stop asking questions! I think I’ve heard part of this verse bandied about as good advice for my whole life: “Don’t cast your pearls before swine.” I suppose what is meant by this is that one’s good effort or good thoughts should not offered to (or wasted on) those who aren’t cultured, educated, or intelligent enough to appreciate them. A lot of biblical commentaries say the verse is a warning by Jesus to his followers that we should not offer biblical doctrine to those who are unable to value and appreciate it, but I don’t think it’s that at all . . . not when one considers the whole text. ~ This proverb appears at the end of the so-called “Sermon on the Mount”. It is preceded by the advice to take care of one’s own problems before criticizing another (“Why do you see the speck in your neighbor’s eye, but do not notice the log in your own eye?” – Matt. 7:3) It is followed by admonitions to ask, seek, and knock, and a description of God as a caring father. That which precedes and follows this proverb is clear and straight-foward; why would one not take this to be equally plainspoken? In addition, why is the warning at the end of this proverb so often ignored: “they will trample them under foot and turn and maul you”? I don’t believe this admonition is about not offering biblical doctrine to those who are unable to appreciate it, not at all! However, it might be about setting that aside for the moment while something else is attended to. ~ I have read commentary actually suggesting that what Jesus is saying to not throw to the dogs (and his hearers would have understood these to be roving packs of wild dogs), the “holy things,” are the choice parts of the animals sacrificed in the Temple, the parts that are supposed to be God’s! C’mon!!! Would a wild dog thrown a t-bone steak trample it under foot and maul the person giving it? No! The dog would devour that meat and beg for more. As a metaphor for not sharing the gospel (“biblical doctrine”), that’s rather a massive fail! Wouldn’t one want your recipients to “feed upon” the gospel and seek more? ~ And note this also, nowhere here does Jesus suggest that one shouldn’t throw something to the dogs, or cast something before the swine. ~ So here’s what I’m thinking today. What this is is good advice to consider carefully what you are throwing or casting in your mission work and outreach, and when you are throwing it. To dogs, throw that which dogs need. Dogs don’t need “holy things”. Wild dogs have very basic needs: food, water, shelter. If they have those, they might be tamed; “holy things” like companionship and affection might be offered later. I don’t know enough about wild pigs (or any pigs, for that matter), but I suspect the message is the same. Give them that which is meaningful and useful for them, and leave the jewelry for later. ~ If this admonition, this proverb is metaphorical of anything, it is a metaphor for doing for others in the way that most and best meets the needs of the moment – not the needs of the giver to “spread the gospel”, but the needs of the recipient whatever they may be. It’s just another way of saying, “Love your neighbor as yourself.” (He might have said, “Do unto the dogs and the swine as you would have others do unto you,” but that just doesn’t have that learned-rabbi ring to it, does it?)

I think I’ve heard part of this verse bandied about as good advice for my whole life: “Don’t cast your pearls before swine.” I suppose what is meant by this is that one’s good effort or good thoughts should not offered to (or wasted on) those who aren’t cultured, educated, or intelligent enough to appreciate them. A lot of biblical commentaries say the verse is a warning by Jesus to his followers that we should not offer biblical doctrine to those who are unable to value and appreciate it, but I don’t think it’s that at all . . . not when one considers the whole text. ~ This proverb appears at the end of the so-called “Sermon on the Mount”. It is preceded by the advice to take care of one’s own problems before criticizing another (“Why do you see the speck in your neighbor’s eye, but do not notice the log in your own eye?” – Matt. 7:3) It is followed by admonitions to ask, seek, and knock, and a description of God as a caring father. That which precedes and follows this proverb is clear and straight-foward; why would one not take this to be equally plainspoken? In addition, why is the warning at the end of this proverb so often ignored: “they will trample them under foot and turn and maul you”? I don’t believe this admonition is about not offering biblical doctrine to those who are unable to appreciate it, not at all! However, it might be about setting that aside for the moment while something else is attended to. ~ I have read commentary actually suggesting that what Jesus is saying to not throw to the dogs (and his hearers would have understood these to be roving packs of wild dogs), the “holy things,” are the choice parts of the animals sacrificed in the Temple, the parts that are supposed to be God’s! C’mon!!! Would a wild dog thrown a t-bone steak trample it under foot and maul the person giving it? No! The dog would devour that meat and beg for more. As a metaphor for not sharing the gospel (“biblical doctrine”), that’s rather a massive fail! Wouldn’t one want your recipients to “feed upon” the gospel and seek more? ~ And note this also, nowhere here does Jesus suggest that one shouldn’t throw something to the dogs, or cast something before the swine. ~ So here’s what I’m thinking today. What this is is good advice to consider carefully what you are throwing or casting in your mission work and outreach, and when you are throwing it. To dogs, throw that which dogs need. Dogs don’t need “holy things”. Wild dogs have very basic needs: food, water, shelter. If they have those, they might be tamed; “holy things” like companionship and affection might be offered later. I don’t know enough about wild pigs (or any pigs, for that matter), but I suspect the message is the same. Give them that which is meaningful and useful for them, and leave the jewelry for later. ~ If this admonition, this proverb is metaphorical of anything, it is a metaphor for doing for others in the way that most and best meets the needs of the moment – not the needs of the giver to “spread the gospel”, but the needs of the recipient whatever they may be. It’s just another way of saying, “Love your neighbor as yourself.” (He might have said, “Do unto the dogs and the swine as you would have others do unto you,” but that just doesn’t have that learned-rabbi ring to it, does it?) Today’s Daily Office gospel is the Matthean version of what has come to be known as “the Lord’s Prayer.” (I remember someone years ago suggesting that it would better be called “the Disciple’s Prayer” since it is not a prayer actually said by Jesus, but rather one he instructs his disciples to say. Good point, but probably a losing argument.) Anglican prayer books, of course, lift the word trespass out of Jesus’ subsequent commentary in verses 14-15 and substitute it for the debt language in the prayer itself. The “trespass” version is the one I learned during a Methodist childhood and then found in the Episcopal Church when I made that move in high school. Thus, the “debt” version is always jarring on my ears; it makes God sound like some sort of cosmic bookkeeper! These days, I prefer the modern translation that petition, “Forgive us our sins” because, after all, that is what we’re talking about! ~ I also prefer the language here in the penultimate petition, “Do not bring us to the time of trial.” The traditional liturgical version, and even the modernized version in the American BCP, render this as “Do not lead us into temptation” which is similar to the King James translation of Scripture. It’s always struck me as a particularly poor translation theologically. I can make sense of a God who might impose a trial at some time . . . a God who would “lead us into temptation” sounds like a trickster to me. I’m not into Loki or Coyote worship, personally. I’m glad for the modern translation, although it was rejected by the liturgists who put together the most current American BCP. ~ Anyway, I’ve been thinking about the Lord’s Prayer all day because of this reading. I say it every day, of course, as part of the Daily Office, so I should think about it more, but I don’t. I just say it. Like some mantra of meaningless nonsense syllables meant to put one into a trance-like state. For all the thought I usually put into it, I could be reciting a laundry ticket or a shopping list. Prayer shouldn’t be like that. It should be intentional; it should be thoughtful and well-considered. I must work on that. Otherwise, God might as well be a trickster or a bookkeeper . . . or both. Would that mean that God is a supernatural embezzler? Or . . . not praying thoughtfully, is that what I am?

Today’s Daily Office gospel is the Matthean version of what has come to be known as “the Lord’s Prayer.” (I remember someone years ago suggesting that it would better be called “the Disciple’s Prayer” since it is not a prayer actually said by Jesus, but rather one he instructs his disciples to say. Good point, but probably a losing argument.) Anglican prayer books, of course, lift the word trespass out of Jesus’ subsequent commentary in verses 14-15 and substitute it for the debt language in the prayer itself. The “trespass” version is the one I learned during a Methodist childhood and then found in the Episcopal Church when I made that move in high school. Thus, the “debt” version is always jarring on my ears; it makes God sound like some sort of cosmic bookkeeper! These days, I prefer the modern translation that petition, “Forgive us our sins” because, after all, that is what we’re talking about! ~ I also prefer the language here in the penultimate petition, “Do not bring us to the time of trial.” The traditional liturgical version, and even the modernized version in the American BCP, render this as “Do not lead us into temptation” which is similar to the King James translation of Scripture. It’s always struck me as a particularly poor translation theologically. I can make sense of a God who might impose a trial at some time . . . a God who would “lead us into temptation” sounds like a trickster to me. I’m not into Loki or Coyote worship, personally. I’m glad for the modern translation, although it was rejected by the liturgists who put together the most current American BCP. ~ Anyway, I’ve been thinking about the Lord’s Prayer all day because of this reading. I say it every day, of course, as part of the Daily Office, so I should think about it more, but I don’t. I just say it. Like some mantra of meaningless nonsense syllables meant to put one into a trance-like state. For all the thought I usually put into it, I could be reciting a laundry ticket or a shopping list. Prayer shouldn’t be like that. It should be intentional; it should be thoughtful and well-considered. I must work on that. Otherwise, God might as well be a trickster or a bookkeeper . . . or both. Would that mean that God is a supernatural embezzler? Or . . . not praying thoughtfully, is that what I am? I’ve been fascinated by the Shekhinah, which is what the cloud and fire described here are all about, for years. The Hebrew word which names the pillar of fire and cloud which accompanied the escaped slaves on their trek across the Sinai desert means “the Presence”, i.e., the presence of God. Whether the Shekhinah is separate from God has been a matter of some debate in Judaism for centuries. Moses Maimonides, also known as Rambam, the 12th Century Egyptian Jewish philosopher, believed the Shekhinah is a distinct entity, a light created to be an intermediary between God and the world. In the next century, the Spanish Rabbi Nahmanides, known as Ramban, disagreed; he considered the Shekhinah to be the essence of God manifested in distinct form. ~ The Shekhinah was believed to be present in the First Temple, but not the Second. In the absence of a Temple, later rabbis have suggested that the Shekhinah appears in a variety of circumstances: when two or three study the Torah together, when a minyan (ten men) pray, when the mysticism of the Merkabah (the divine chariot) is explained, when the Law is studied at night, and when the Shema is recited. God’s Presence is said to be attracted to prayer, to hospitality, to acts of benevolence, to chastity, and to peace and faithfulness in married life. ~ The idea that the Shekhinah is present when two or three study Scripture reminds me of Jesus’ promise: “Where two or three are gathered in my name, I am there among them.” (Matthew 18:20) The Daily Office, both Morning Prayer and Evening Prayer, ends with a collect said to have been written by St. John Chrysostom which recalls this promise: “You have promised through your well-beloved Son that when two or three are gathered together in his Name you will be in the midst of them.” ~ The Book of Exodus makes it very clear that the People of God were terrified of the Shekhinah. They would not go near it; only Moses could do so and, as this bit demonstrates, even he could not approach sometimes. Smart people, those ancient Hebrews! They understood the Power they were dealing with. Not so, us modern folks. Christian writer Annie Dillard, in her book Teaching a Stone to Talk (Harper & Row 1982), makes this point in an oft-quote observation: “Does any-one have the foggiest idea what sort of power we so blithely invoke? Or, as I suspect, does no one believe a word of it? The churches are children playing on the floor with their chemistry sets, mixing up a batch of TNT to kill a Sunday morning. It is madness to wear ladies’ straw hats and velvet hats to church; we should all be wearing crash helmets. Ushers should issue life preservers and signal flares; they should lash us to our pews. For the sleeping god may wake some day and take offense, or the waking god may draw us out to where we can never return.” ~ We are, indeed, children playing with dynamite – or maybe even playing with a nuclear bomb! Thank Heaven our God is a playful god. I do not believe God will awaken and take offense, but I do believe God wants us to move beyond games, to stop simply playing with the power his Presence provides, and to start using that power for good!

I’ve been fascinated by the Shekhinah, which is what the cloud and fire described here are all about, for years. The Hebrew word which names the pillar of fire and cloud which accompanied the escaped slaves on their trek across the Sinai desert means “the Presence”, i.e., the presence of God. Whether the Shekhinah is separate from God has been a matter of some debate in Judaism for centuries. Moses Maimonides, also known as Rambam, the 12th Century Egyptian Jewish philosopher, believed the Shekhinah is a distinct entity, a light created to be an intermediary between God and the world. In the next century, the Spanish Rabbi Nahmanides, known as Ramban, disagreed; he considered the Shekhinah to be the essence of God manifested in distinct form. ~ The Shekhinah was believed to be present in the First Temple, but not the Second. In the absence of a Temple, later rabbis have suggested that the Shekhinah appears in a variety of circumstances: when two or three study the Torah together, when a minyan (ten men) pray, when the mysticism of the Merkabah (the divine chariot) is explained, when the Law is studied at night, and when the Shema is recited. God’s Presence is said to be attracted to prayer, to hospitality, to acts of benevolence, to chastity, and to peace and faithfulness in married life. ~ The idea that the Shekhinah is present when two or three study Scripture reminds me of Jesus’ promise: “Where two or three are gathered in my name, I am there among them.” (Matthew 18:20) The Daily Office, both Morning Prayer and Evening Prayer, ends with a collect said to have been written by St. John Chrysostom which recalls this promise: “You have promised through your well-beloved Son that when two or three are gathered together in his Name you will be in the midst of them.” ~ The Book of Exodus makes it very clear that the People of God were terrified of the Shekhinah. They would not go near it; only Moses could do so and, as this bit demonstrates, even he could not approach sometimes. Smart people, those ancient Hebrews! They understood the Power they were dealing with. Not so, us modern folks. Christian writer Annie Dillard, in her book Teaching a Stone to Talk (Harper & Row 1982), makes this point in an oft-quote observation: “Does any-one have the foggiest idea what sort of power we so blithely invoke? Or, as I suspect, does no one believe a word of it? The churches are children playing on the floor with their chemistry sets, mixing up a batch of TNT to kill a Sunday morning. It is madness to wear ladies’ straw hats and velvet hats to church; we should all be wearing crash helmets. Ushers should issue life preservers and signal flares; they should lash us to our pews. For the sleeping god may wake some day and take offense, or the waking god may draw us out to where we can never return.” ~ We are, indeed, children playing with dynamite – or maybe even playing with a nuclear bomb! Thank Heaven our God is a playful god. I do not believe God will awaken and take offense, but I do believe God wants us to move beyond games, to stop simply playing with the power his Presence provides, and to start using that power for good! This psalm is not the only time Holy Scripture reports God’s displeasure with the sacrifice of animals. Consider these words from the first chapter of the Book of Isaiah, “What to me is the multitude of your sacrifices? says the Lord; I have had enough of burnt offerings of rams and the fat of fed beasts; I do not delight in the blood of bulls, or of lambs, or of goats. When you come to appear before me, who asked this from your hand? Trample my courts no more; bringing offerings is futile; incense is an abomination to me. New moon and sabbath and calling of convocation – I cannot endure solemn assemblies with iniquity.” (Isa. 1:11-13) Despite all of the ritual directions found in the Law and in the Histories (see, e.g., Exodus 29, Leviticus 1, Numbers 7, and 1 Kings 18), the Psalmist, the first Isaiah, and especially the Prophet Micah make it very clear that sacrificing innocent animals is not what Judaism (or religion in general) is all about. Micah writes, “‘With what shall I come before the Lord, and bow myself before God on high? Shall I come before him with burnt offerings, with calves a year old? Will the Lord be pleased with thousands of rams, with ten thousands of rivers of oil? Shall I give my firstborn for my transgression, the fruit of my body for the sin of my soul?’ He has told you, O mortal, what is good; and what does the Lord require of you but to do justice, and to love kindness, and to walk humbly with your God?” (Micah 6:6-8) It may be that doing justice, loving kindness, and walking with God may (and often does) require one to give up one’s possessions, one’s livelihood, even one’s life. But such “sacrifice” without the demanded ethical basis, sacrifice done only to curry favor with God, is not what God asks or wants. ~ It is from this ethical stream in ancient Judaism that Christianity flows. It is unfortunate that early Christian writers looked back to the sacrificial practices of the Temple to find an analog to crucifixion of Jesus; we might have seen the Christian religion develop differently if, like the writers of the Gospels, they had looked more to the prophets. Jesus certainly did: “‘You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your mind.’ This is the greatest and first commandment. And a second is like it: ‘You shall love your neighbor as yourself.’ On these two commandments hang all the law and the prophets.” (Matthew 22:37-40) ~ So spare that bull! Sacrifices of animals (or their modern analogs, whatever they may be) are not the sacrifices that demonstrate love of God and love of neighbor. Rather, the core of ethical religion is as the writer of the Letter to Hebrews said: “Do not neglect to do good and to share what you have, for such sacrifices are pleasing to God.” (Heb. 13:16)

This psalm is not the only time Holy Scripture reports God’s displeasure with the sacrifice of animals. Consider these words from the first chapter of the Book of Isaiah, “What to me is the multitude of your sacrifices? says the Lord; I have had enough of burnt offerings of rams and the fat of fed beasts; I do not delight in the blood of bulls, or of lambs, or of goats. When you come to appear before me, who asked this from your hand? Trample my courts no more; bringing offerings is futile; incense is an abomination to me. New moon and sabbath and calling of convocation – I cannot endure solemn assemblies with iniquity.” (Isa. 1:11-13) Despite all of the ritual directions found in the Law and in the Histories (see, e.g., Exodus 29, Leviticus 1, Numbers 7, and 1 Kings 18), the Psalmist, the first Isaiah, and especially the Prophet Micah make it very clear that sacrificing innocent animals is not what Judaism (or religion in general) is all about. Micah writes, “‘With what shall I come before the Lord, and bow myself before God on high? Shall I come before him with burnt offerings, with calves a year old? Will the Lord be pleased with thousands of rams, with ten thousands of rivers of oil? Shall I give my firstborn for my transgression, the fruit of my body for the sin of my soul?’ He has told you, O mortal, what is good; and what does the Lord require of you but to do justice, and to love kindness, and to walk humbly with your God?” (Micah 6:6-8) It may be that doing justice, loving kindness, and walking with God may (and often does) require one to give up one’s possessions, one’s livelihood, even one’s life. But such “sacrifice” without the demanded ethical basis, sacrifice done only to curry favor with God, is not what God asks or wants. ~ It is from this ethical stream in ancient Judaism that Christianity flows. It is unfortunate that early Christian writers looked back to the sacrificial practices of the Temple to find an analog to crucifixion of Jesus; we might have seen the Christian religion develop differently if, like the writers of the Gospels, they had looked more to the prophets. Jesus certainly did: “‘You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your mind.’ This is the greatest and first commandment. And a second is like it: ‘You shall love your neighbor as yourself.’ On these two commandments hang all the law and the prophets.” (Matthew 22:37-40) ~ So spare that bull! Sacrifices of animals (or their modern analogs, whatever they may be) are not the sacrifices that demonstrate love of God and love of neighbor. Rather, the core of ethical religion is as the writer of the Letter to Hebrews said: “Do not neglect to do good and to share what you have, for such sacrifices are pleasing to God.” (Heb. 13:16)