====================

A homily offered by the Rev. Dr. C. Eric Funston on the 4th Sunday after the Epiphany, January 29, 2017, to the people of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Medina, Ohio, where Fr. Funston is rector.

(The lessons for the day are from the Revised Common Lectionary, Year A: Micah 6:1-8; Psalm 15; 1 Corinthians 1:18-31; and St. Matthew 5:1-12. These lessons can be read at The Lectionary Page.)

====================

Have you ever had the experience of a long-forgotten memory rushing back upon you and just knocking you for a loop? Something like an odor or a song or a picture brings it back and the details hit you like a sledge hammer. That happened to me on Monday evening.

Have you ever had the experience of a long-forgotten memory rushing back upon you and just knocking you for a loop? Something like an odor or a song or a picture brings it back and the details hit you like a sledge hammer. That happened to me on Monday evening.

We were watching a biography of Rachel Carson, author of the book Silent Spring, on PBS. It was very well done. The program opened a floodgate of memory of my childhood; what did it was a segment in the show in which film of atomic bomb explosions was shown. I remembered two occasions when my father and I, with others, went out into the Nevada desert to see the mushroom clouds. The first was in the summer of 1957 when I was 4-1/2 years old: my dad, my brother, and I went to the test site at the invitation of a physics professor colleague of my father (my dad was an accountant, but he also taught math and accountancy at what was then called Nevada Southern University). The second in December of that same year, after I had started kindergarten and my class, together with several others from John S. Park Elementary School in Las Vegas, went to the test site on field trip and my father, who was self-employed and could take time to do those things, went along as a chaperone.

All the details of those excursions into the Nevada desert, and seeing those glowing clouds rise miles and miles away to the northeast from where we were watching, and my father’s reaction to them, all came rushing back.

After both of those experiences, I can remember my dad for a few weeks being what my grandmother would have called “cranky.” Things around our house got chaotic. The person who was supposed to be the adult in charge got mean and spiteful, and did things that were erratic and made no sense. My dad, the person who was supposed to be the adult in charge, just seemed to be angry and crazy all the time.

I suspect that what he was was drunk, and I suspect he was drunk because he was scared to death of nuclear war. My dad was a decorated combat veteran of World War II who had been badly wounded in the Battle of the Bulge; he’d been awarded both the Purple Heart and the Bronze Star for heroism. He was in constant pain during the short period of my life that he was a part of it. I know now, but didn’t know then, that he was an alcoholic who self-medicated his pain and his fear with booze. In March 1958, he drove away from our house after a drunken argument with my mother and never came back; he killed himself in a single-vehicle roll-over accident on the highway between Las Vegas and Kingman, Arizona. The family guesswork is that he was trying to drive back to my grandparents’ home, his childhood home, in Kansas.

Why do I share those memories with you this morning? I suppose it is because whenever I read the words, “When Jesus saw the crowds, he went up the mountain; and after he sat down, his disciples came to him. Then he began to speak, and taught them . . . .” (Mt 5:1-2) what I envision is something very like the desert hillside from which we viewed those atomic bomb blasts. And when I read St. Paul writing to the Corinthians that God “will destroy the wisdom of the wise, and the discernment of the discerning [he] will thwart” (1 Cor 1:19) and that “God’s weakness is stronger than human strength” (v. 25), it is those mushroom clouds that metaphorically come to mind.

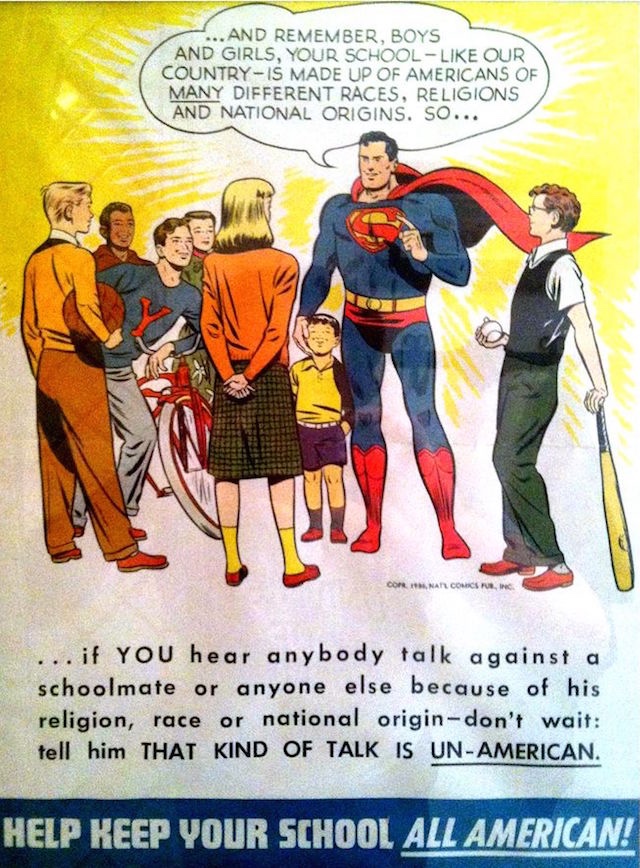

But I have another childhood memory which is also excited by these lessons, and that is sitting down in front of our small, black-and-white television every week and hearing these words:

Yes, it’s Superman . . . strange visitor from another planet, who came to Earth with powers and abilities far beyond those of mortal men! Superman . . . who can change the course of mighty rivers, bend steel in his bare hands, and who, disguised as Clark Kent, mild-mannered reporter for a great metropolitan newspaper, fights a never-ending battle for truth, justice, and the American way!

I couldn’t help but remember that famous opening sequence each time I sat down this week to consider the words of the Prophet Micah:

He has told you, O mortal, what is good;

and what does the Lord require of you

but to do justice, and to love kindness,

and to walk humbly with your God? (Micah 6:8)

Truth, justice, kindness, humility . . . Biblical values that all seem to be jumbled together with the American way in my Superman-TV-program-educated mind, or at least I feel like they should be . . . and I am too often confronted with the reality that they are not.

This week, one thing I noticed particularly about the Superman intro that I’d not considered before is that it isn’t in the Superman persona, that incredible being who could stand right next to an exploding atomic bomb without being injured, that the alien immigrant Kal-El “fights [the] never-ending battle for truth, justice, and the American way.” No, it is in the guise of “mild-mannered reporter” Clark Kent that the refugee from the destroyed planet Krypton does so! It is the journalist character, not the superhero, “who speaks the truth from his heart” and upon whose tongue there is no guile!

So I have these two memories that rush into my consciousness when I read and consider these lessons, images of nuclear explosions and memories of my angry, alcoholic father, mythic superheroes, and “mild-mannered reporters” fighting “never-ending battles.” They color my understanding of these Scriptures and, yet, I must admit that they also clash with them for there is nothing here about war, about anger, about fighting, about battles. If anything, they seem to be quite the opposite!

The beatitudes, these statements of blessedness which we find here in Matthew and in a rather different form in Luke’s gospel, for example, raise for us the question, “Are they a programmatic outline for the church’s social justice ministry or are they simply words of comfort and encouragement for Jesus’ down-trodden original audience?” In his essay on Luke’s gospel, Southern Baptist scholar Robert H. Stein argues for the second; he writes:

Are the beatitudes to be interpreted as requirements for entering God’s kingdom or as eschatological pronouncements of blessing upon believers? In other words, are the beatitudes an evangelistic exhortation for salvation or pastoral words of comfort and encouragement, a kind of congratulation, to those who already possess faith? For several reasons they should be understood as the latter. (Stein, Robert H., Luke, The New American Commentary, Vol 24, B&H Publishing: Nashville, 1991, page 199)

On the other hand, Lutheran seminary professor Karoline Lewis takes the opposite position. “The Beatitudes,” she writes, “are not just blessings but a call to action.”

[T]he Beatitudes are a call to action to point out just who Jesus really is. Perhaps not the Jesus you want. Perhaps the Jesus who likely rubs you the wrong way. Perhaps the Jesus that tells you the truth about yourself. The Jesus who reminds you, at the most inconvenient times and places, what the Kingdom of Heaven is all about.

The Beatitudes are a call to action to be church, a call to action to make Jesus present and visible and manifest when the world tries desperately to silence those who speak the truth . . . . (Lewis, Righteous Living)

I wonder if they might be neither . . . or, perhaps, both, in the same way that nuclear energy can be both destructive weapon in the form of an atomic bomb and source of constructive power as in an electrical power plant, or in the same way that Kal-El can be both the mighty indestructible “man of steel” and the mild-mannered journalistic champion of truth. Perhaps the beatitudes are nothing more nor less than Jesus’ instruction to his disciples on how to recognize blessedness. “Not how to become blessed, or even to bless each other, but rather to recognize who is already blessed by God.” (Lose, Recognizing Blessing) Their blessings are spiritual poverty, mourning, meekness, desire for righteousness, mercy, purity of heart, peacemaking, and persecution.

Several years ago, a Disciples of Christ pastor and professor named Lance Pape wondered, “To which of these blessings do our national leaders refer when they insist that ‘God Bless[es] America!'” And he answered his own question:

To none of these, for our national creed is one of optimism (not mourning), confidence (not poverty of spirit), and abundance (not hunger or thirst of any kind), and it is in service of such things that we invoke and assume the blessing of God. And so we live by those other beatitudes:

- Blessed are the well-educated, for they will get the good jobs.

- Blessed are the well-connected, for their aspirations will not go unnoticed.

- Blessed are you when you know what you want, and go after it with everything you’ve got, for God helps those who help themselves.

If we are honest, we must admit that the world Jesus asserts as fact, is not the world we have made for ourselves. (Pape, Working Preacher Commentary on Matthew 5:1-12)

In the world we have made for ourselves we see the bombs, the anger, the war, and we look for the “man of steel” to save us, to fly in singing “Here I come to save the day” (although I do know that’s a different superhero) and then taking us away to some kingdom of heaven in the sky. We know better, though, don’t we?

When Jesus teaches us to recognize blessedness in the Beatitudes, he teaches us to “recognize that God’s kingdom isn’t a place far away but is found whenever we honor each other as God’s children, bear each other’s burdens, bind each other’s wounds, and meet each other’s needs.” (Lose, Op. Cit.) He teaches us, as the Prophet Micah taught the ancient Israelites, “to do justice, and to love kindness, and to walk humbly with [our] God” (Micah 6:8). He teaches us, as the Psalmist taught in the liturgy of the ancient Temple, to lead a blameless life, to do what is right, to speak the truth from his heart, to have no guile upon our tongues, to do no evil to our friend, to heap no contempt upon our neighbors, and to reject what is wicked when we see it (Ps 15). That is the Christian way. And child of the atomic 1950s and devotee of television’s Superman that I am, I still believe it is, or at least it should be, the American way.

====================

Father Funston is the rector of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Medina, Ohio.

May God be merciful to us and bless us, show us the light of his countenance and come to us. (Ps. 67:1) Amen.

May God be merciful to us and bless us, show us the light of his countenance and come to us. (Ps. 67:1) Amen. On the day after the general election, a Presbyterian clergyman in Iowa, a married gay man, found a computer-printed note tucked under his car’s windshield wiper addressed to “Father Homo.” The text of the note began with the question “How does it feel to have Trump as your president?” and was both belittling and threatening. The same day a softball dugout in Island Park in Wellsville, New York, was defaced with graffiti reading “Make America White Again,” accompanied by a large swastika. The next day, students at nearby Canisius College, a Jesuit institution, found a black baby doll with a noose tied around its neck in the freshman dormitory elevator, and students at Wellesley College in Massachusetts witnessed two young white men drive a truck through their campus flying a Trump campaign banner, yelling “Make American Great Again,” and spitting on African-American young women.

On the day after the general election, a Presbyterian clergyman in Iowa, a married gay man, found a computer-printed note tucked under his car’s windshield wiper addressed to “Father Homo.” The text of the note began with the question “How does it feel to have Trump as your president?” and was both belittling and threatening. The same day a softball dugout in Island Park in Wellsville, New York, was defaced with graffiti reading “Make America White Again,” accompanied by a large swastika. The next day, students at nearby Canisius College, a Jesuit institution, found a black baby doll with a noose tied around its neck in the freshman dormitory elevator, and students at Wellesley College in Massachusetts witnessed two young white men drive a truck through their campus flying a Trump campaign banner, yelling “Make American Great Again,” and spitting on African-American young women. Languages and the study of languages fascinate me – if you didn’t know that before this series on the Lord’s Prayer, you probably know it now – and I am therefore always keenly aware of the difficulty of fully appreciating the Holy Scripture if we only consider the meaning of the English translation.

Languages and the study of languages fascinate me – if you didn’t know that before this series on the Lord’s Prayer, you probably know it now – and I am therefore always keenly aware of the difficulty of fully appreciating the Holy Scripture if we only consider the meaning of the English translation.  This morning, after I took the dog for her walk and poured a cup of coffee, I turned on my computer and found a message from my friend Melania, who is from Naples but is currently working in Spain. We were students together in Ireland. This is her message:

This morning, after I took the dog for her walk and poured a cup of coffee, I turned on my computer and found a message from my friend Melania, who is from Naples but is currently working in Spain. We were students together in Ireland. This is her message:  Let’s talk about Jonah. When I say something like “Let’s talk about Jonah,” I have to be more specific. I have to tell you whether I mean “Let’s talk about the Book of Jonah” or “Let’s talk about the character of Jonah portrayed in the book” or “Let’s talk about the Prophet Jonah.” In this case, I mean all three: let’s talk about the book, character, and the prophet — although, to be honest, the prophet’s name really isn’t Jonah; we don’t know the prophet’s name — and that, I hope, will be clearer in a moment.

Let’s talk about Jonah. When I say something like “Let’s talk about Jonah,” I have to be more specific. I have to tell you whether I mean “Let’s talk about the Book of Jonah” or “Let’s talk about the character of Jonah portrayed in the book” or “Let’s talk about the Prophet Jonah.” In this case, I mean all three: let’s talk about the book, character, and the prophet — although, to be honest, the prophet’s name really isn’t Jonah; we don’t know the prophet’s name — and that, I hope, will be clearer in a moment.

This part of Isaiah was written shortly after the return of the Jewish exiles from Babylon, which Cyrus of Persia had allowed in the middle of the 6th Century BCE. Isaiah (on God’s behalf) was promising two things with these images of laborers enjoying the fruits of their own efforts: first, that the people would no longer be (if not slaves) subjugated workers of foreign (or domestic) overlords and, second, that there would be peace. Israel’s and Judah’s history had been one of regular (if not constant) upheaval with invaders coming in and taking control of the vineyards and seizing the people’s lands and homes: the simple planting of vineyards with an expectation of enjoying the crop was a metaphor of peace and security.

This part of Isaiah was written shortly after the return of the Jewish exiles from Babylon, which Cyrus of Persia had allowed in the middle of the 6th Century BCE. Isaiah (on God’s behalf) was promising two things with these images of laborers enjoying the fruits of their own efforts: first, that the people would no longer be (if not slaves) subjugated workers of foreign (or domestic) overlords and, second, that there would be peace. Israel’s and Judah’s history had been one of regular (if not constant) upheaval with invaders coming in and taking control of the vineyards and seizing the people’s lands and homes: the simple planting of vineyards with an expectation of enjoying the crop was a metaphor of peace and security.  I want to ask you to read along as I re-read the collect for the day, the particular prayer of the Fourth Sunday in Advent: “Purify our conscience . . . . ” That’s enough, just those three words: “Purify our conscience . . . . ” Don’t you think that’s asking a lot of God? I mean really . . . purify the human conscience, that place in ourselves where we know all the wrongs we have done. Tall order, purifying that! But that’s what the prayer asks and in doing so it draws on the language of the Letter to Hebrews from which our second lesson today is taken.

I want to ask you to read along as I re-read the collect for the day, the particular prayer of the Fourth Sunday in Advent: “Purify our conscience . . . . ” That’s enough, just those three words: “Purify our conscience . . . . ” Don’t you think that’s asking a lot of God? I mean really . . . purify the human conscience, that place in ourselves where we know all the wrongs we have done. Tall order, purifying that! But that’s what the prayer asks and in doing so it draws on the language of the Letter to Hebrews from which our second lesson today is taken. Sound familiar? Jesus sounded a lot like Micah at times:

Sound familiar? Jesus sounded a lot like Micah at times: