Revised Common Lectionary for the Fourth Sunday in Lent, Year B: Numbers 21:4-9; Psalm 107:1-3, 17-22; Ephesians 2:1-10; and John 3:14-21

Continuing our series of sermons in answer to parishioner questions, today we will explore fasting. A member of the congregation asked, “What is fasting and why do we do it?”

The simple answer is that fasting is going without some or all food or drink or both for a defined period of time. An absolute fast is abstinence from all food and liquid for a period of at least one day, sometimes for several days. Other fasts may be only partially restrictive, limiting particular foods or substance. The fast may also be intermittent in nature; for example, Muslims fast during the daylight hours of the month of Ramadan which is intended to teach Muslims patience, spirituality, humility, and submissiveness to God. Fasting as a spiritual practice is common to all major religions. Mahatma Gandhi once noted:

The simple answer is that fasting is going without some or all food or drink or both for a defined period of time. An absolute fast is abstinence from all food and liquid for a period of at least one day, sometimes for several days. Other fasts may be only partially restrictive, limiting particular foods or substance. The fast may also be intermittent in nature; for example, Muslims fast during the daylight hours of the month of Ramadan which is intended to teach Muslims patience, spirituality, humility, and submissiveness to God. Fasting as a spiritual practice is common to all major religions. Mahatma Gandhi once noted:

Every … religion of any importance appreciates the spiritual value of fasting … For one thing, identification with the starving poor is a meaningless term without the experience behind it. But … even an eighty-day fast may fail to rid a person of pride, selfishness, ambition, and the like. Fasting is merely a prop. But as a prop to a tottering structure is of essential value, so is the prop of fasting of inestimable value for a struggling soul.

In the Bible, the people of God in both the Hebrew and Christian Scriptures fasted for a variety of reasons:

- They were facing a crisis. For example, the prophet Joel called for a fast to avert the judgment of God. (Joel 1:14, 2:12-15), and the people of Nineveh, in response to Jonah’s prophecy, fasted to forestall God’s judgment (Jonah 3:7).

- They were seeking God’s protection and deliverance. For example, King Jehoshaphat in the Second Book of Chronicles proclaimed a fast seeking victory for Judah over the attaching Moabites and Ammonites (2 Chron. 20:3).

- They had been called to repentance and renewal. The Psalmist, for example, in Psalm 109 cries:

O Lord my God,

oh, deal with me according to your Name; *

for your tender mercy’s sake, deliver me.

My knees are weak through fasting, *

and my flesh is wasted and gaunt. (vv. 20,23)

- They were asking God for guidance. Moses fasted for forty days and forty nights on Mount Sinai before he received the tablets on the mountain with God. (Deut. 9) St. Paul did not eat or drink anything for three days after he converted on the road to Damascus. (Acts 9:9)

- They were humbling themselves in worship. The Book of Acts reports that it was with “fasting and praying” that the members of the church in Antioch “laid their hands on [Barnabas and Saul] and sent them off.” (Acts 13:3)

So fasting has a long and venerable history in all religions including our own. Indeed, Jesus assumed that his followers would fast. You may remember the lesson from Matthew’s Gospel which is always read on Ash Wednesday in which Jesus admonishes the disciples:

Whenever you fast, do not look dismal, like the hypocrites, for they disfigure their faces so as to show others that they are fasting. Truly I tell you, they have received their reward. But when you fast, put oil on your head and wash your face, so that your fasting may be seen not by others but by your Father who is in secret; and your Father who sees in secret will reward you. (Matthew 6:16-18)

In this passage Jesus doesn’t say, “If you pray … if you give … if you fast” but rather “when you pray … when you give … when you fast.” He simply expected his followers to do so. Did you know that fasting is mentioned more than 30 times in the New Testament? For a Christian, then, fasting is not an option. It should not be an oddity. Fasting, according to Jesus, is just a given.

During this season of Lent when we “give something up,” we are engaging in the spiritual discipline of the fast. We do so in remembrance of and in solidarity with Jesus during his forty days in the desert. We do so in remembrance of and in solidarity with our spiritual ancestors, the Hebrews, who spent forty years in the desert, often without food or sustenance. In today’s reading from the Book of Numbers, for example, “The people spoke against God and against Moses, ‘Why have you brought us up out of Egypt to die in the wilderness? For there is no food and no water, and we detest this miserable food.’” God’s wrath, of course, was kindled against them because of their complaining, but they were humbled by their privation. When we “give up something” (whether it be food or drink or some other thing that we enjoy), we are fasting and our fasting is a reminder of our own humility and own hunger for God. By refusing to feed our physical appetites, what St. Paul in today’s epistle lesson calls “the passions of our flesh” or “the desires of flesh and senses,” we become aware of our spiritual hunger.

The Baptist preacher and author John Piper, in his book A Hunger for God: Desiring God through Fasting and Prayer, encourages fasting with these words:

If you don’t feel strong desires for the manifestation of the glory of God, it is not because you have drunk deeply and are satisfied. It is because you have nibbled so long at the table of the world. Your soul is stuffed with small things, and there is no room for the great. God did not create you for this. There is an appetite for God. And it can be awakened. I invite you to turn from the dulling effects of food and the dangers of idolatry, and to say with some simple fast, “This much, O God, I want you.” (Pg 23)

Fasting is a way to bring into view those things we may need most to set aside but of which we are often unaware. In today’s lesson from John’s Gospel, Jesus tells Nicodemus that in the coming of the Son, “light has come into the world” and then says:

All who do evil hate the light and do not come to the light, so that their deeds may not be exposed. But those who do what is true come to the light, so that it may be clearly seen that their deeds have been done in God. (John 3:20-21)

In his book Celebration of Discipline: The Path to Spiritual Growth, Quaker theologian Richard Foster commends fasting as a way of bringing things to light:

More than any other single discipline, fasting reveals the things that control us. This is a wonderful benefit to the true disciple who longs to be transformed into the image of Jesus Christ. We cover up what is inside us with food and other good things, but in fasting these things surface. If pride controls us, it will be revealed almost immediately. David said, “I humbled myself with fasting” (Ps. 69:10). Anger, bitterness, jealousy, strife, fear – if they are within us, they will surface during fasting. At first we will rationalize that our anger is due to our hunger; then we know that we are angry because the spirit of anger is within us. We can rejoice in this knowledge because we know that healing is available through the power of Christ. (Pg. 48)

But when we fast, we must not delude ourselves into believing that the fasting itself is earning us any “brownie points” – it is not through our good deeds, including our fasting, that we earn salvation. Indeed, we cannot earn salvation. St. Paul reminds us of that forcefully in today’s epistle: “By grace you have been saved through faith, and this is not your own doing; it is the gift of God – not the result of works, so that no one may boast.” (Eph. 2:8-9)

Thinking that the act of fasting itself could earn God’s reward was condemned by God speaking through the Prophet Isaiah:

[You say,] “Why do we fast, but you do not see? Why humble ourselves, but you do not notice?” Look, you serve your own interest on your fast day, and oppress all your workers. Look, you fast only to quarrel and to fight and to strike with a wicked fist. Such fasting as you do today will not make your voice heard on high. Is such the fast that I choose, a day to humble oneself? Is it to bow down the head like a bulrush, and to lie in sackcloth and ashes? Will you call this a fast, a day acceptable to the Lord? Is not this the fast that I choose: to loose the bonds of injustice, to undo the thongs of the yoke, to let the oppressed go free, and to break every yoke? Is it not to share your bread with the hungry, and bring the homeless poor into your house; when you see the naked, to cover them, and not to hide yourself from your own kin? Then your light shall break forth like the dawn, and your healing shall spring up quickly; your vindicator shall go before you, the glory of the Lord shall be your rear guard. (Isa. 58:3-8)

So fasting is a spiritual discipline, but only when done with the proper prayerful attitude, the proper religious understanding – when done “in secret” as Jesus said in the Ash Wednesday reading from Matthew’s Gospel. Fasting is not so much about food, as it is about focus. It is not so much about saying “No” to the body, as it is about saying “Yes” to the Spirit. It is not about doing without; it is about looking within. It is an outward manifestation to an inward cry of the soul, a surfacing of those things that need to be brought to light, not to be condemned, but to be saved.

Let us pray:

Support us, O Lord, with your gracious favor through our Lenten fast; that as we observe it by bodily self-denial, so we may fulfill it with inner sincerity of heart; through Jesus Christ our Lord, who lives and reigns with you and the Holy Spirit, one God, for ever and ever. Amen. (Adapted from Holy Women, Holy Men, Collect for Friday after Ash Wednesday, pg. 34)

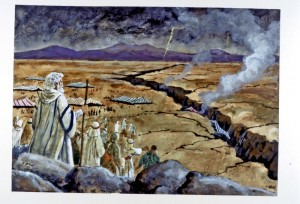

So the story of Korah’s rebellion (which lead me yesterday to give thought to the current leadership crisis in the Episcopal Church) continues in today’s reading and Moses (now with Aaron) is again falling on his face! This time because God, righteously unhappy with the Hebrews because of Korah and his companions, decided to simply wipe them out. Moses and Aaron made the case that this would be (to coin a phrase) overkill. So God relented and decided only to wipe out Korah, his companions, and their families. The rebels “together with their wives, their children, and their little ones” (v. 27) stood before their tents and then “the earth opened its mouth and swallowed them up, along with their households – everyone who belonged to Korah and all their goods.” (v. 32) And just for good measure, 250 Levites who’d been standing around with censers (as instructed by God through Moses) were consumed by fire which “came out from the Lord.” (v. 35). I probably don’t need to tell you that I find this story more than a little troubling! This vengeful warrior god taking out his pique on a large number of people, including small children, is not the god I particularly want to worship! ~ I once had a parishioner who was part of my team of lectors (folks who assist in worship by reading the lessons from Holy Scripture) who refused to read from the Old Testament: “I don’t believe in that god,” she would say. Well, I thought, neither did Marcion, but the church decided he was wrong, that the God of the Old Testament is the same God who is the Father of Jesus Christ, that we do worship that God, and we have to wrestle with the discomfort these ancient writings inflict upon us. Still, I didn’t insist that she read the Old Testament lessons. After all, this sort of reading (as I said) makes me more than a little uncomfortable, too! ~ And that is at it should be. The Hebrew Scriptures are the story of a people’s developing understanding of their God and their relationship with God. That story will have and does have the same sorts of violent and unpalatable events any human history will have. This is why the historical-critical method of studying the Bible is important, for it enables us to grasp what it actually meant to live as one of the Chosen People in any given era. The more accurately we understand the world of the Hebrews, the Israelites, or the church, the more we can see how the people of the Bible understood themselves to be in relationship with God. ~ A daily meditation on the Scriptures is not the place to wrestle with and resolve the difficulties and discomforts passages such as this episode from Numbers create. However, it is a place to suggest that approaching the biblical picture of God with a recognition that the Hebrews progressed in their apprehension of God, appreciating the historical circumstance of the Bible’s stories, allows us to see these stories in as positive a light as possible. Seen in this light, the more brutal parts of the Bible may still communicate valid insights – even to us. We simply don’t have the luxury of saying “I don’t believe in that God”! Rather, we have the responsibility to wrestle with these pictures of God.

So the story of Korah’s rebellion (which lead me yesterday to give thought to the current leadership crisis in the Episcopal Church) continues in today’s reading and Moses (now with Aaron) is again falling on his face! This time because God, righteously unhappy with the Hebrews because of Korah and his companions, decided to simply wipe them out. Moses and Aaron made the case that this would be (to coin a phrase) overkill. So God relented and decided only to wipe out Korah, his companions, and their families. The rebels “together with their wives, their children, and their little ones” (v. 27) stood before their tents and then “the earth opened its mouth and swallowed them up, along with their households – everyone who belonged to Korah and all their goods.” (v. 32) And just for good measure, 250 Levites who’d been standing around with censers (as instructed by God through Moses) were consumed by fire which “came out from the Lord.” (v. 35). I probably don’t need to tell you that I find this story more than a little troubling! This vengeful warrior god taking out his pique on a large number of people, including small children, is not the god I particularly want to worship! ~ I once had a parishioner who was part of my team of lectors (folks who assist in worship by reading the lessons from Holy Scripture) who refused to read from the Old Testament: “I don’t believe in that god,” she would say. Well, I thought, neither did Marcion, but the church decided he was wrong, that the God of the Old Testament is the same God who is the Father of Jesus Christ, that we do worship that God, and we have to wrestle with the discomfort these ancient writings inflict upon us. Still, I didn’t insist that she read the Old Testament lessons. After all, this sort of reading (as I said) makes me more than a little uncomfortable, too! ~ And that is at it should be. The Hebrew Scriptures are the story of a people’s developing understanding of their God and their relationship with God. That story will have and does have the same sorts of violent and unpalatable events any human history will have. This is why the historical-critical method of studying the Bible is important, for it enables us to grasp what it actually meant to live as one of the Chosen People in any given era. The more accurately we understand the world of the Hebrews, the Israelites, or the church, the more we can see how the people of the Bible understood themselves to be in relationship with God. ~ A daily meditation on the Scriptures is not the place to wrestle with and resolve the difficulties and discomforts passages such as this episode from Numbers create. However, it is a place to suggest that approaching the biblical picture of God with a recognition that the Hebrews progressed in their apprehension of God, appreciating the historical circumstance of the Bible’s stories, allows us to see these stories in as positive a light as possible. Seen in this light, the more brutal parts of the Bible may still communicate valid insights – even to us. We simply don’t have the luxury of saying “I don’t believe in that God”! Rather, we have the responsibility to wrestle with these pictures of God. Moses “fell on his face.” This is biblical language for expressing great despair and sadness, not the reaction to a leadership confrontation a modern person would expect. Anger? Yes. Hostility? Yes. Yelling and shouting and public protestation of one’s rightness? Yes. Falling prostrate on the ground in desperate sadness? Not so much. ~ It would appear that in the confrontation of Korah and his compatriots, Moses felt personal responsibility. He believe that what had gone wrong with the Hebrews was his fault. He seems to have believed that he himself had created an atmosphere which had led to less-than-perfect delegated administration and justice. ~ Unfortunately a leadership crisis in the Episcopal Church isn’t resulting in similar behavior from the church’s leadership. In recent months the two highest officials of the church (the Presiding Bishop and the President of the House of Deputies) have had a public squabble over when and how one or the other might communicate with other persons in the church (the cause of the dispute was a video the PB made and sent to members of the House of Deputies, apparently without a “heads-up” to the PHoD). More recently, proposals for the church’s budget for the coming triennium have raised concern among many church members. In response to the first criticisms, the Executive Council issued a statement which was wholey inadequate (in my opinion) and failed to take responsibility. Then the PB (apparently distancing herself from the Executive Council of which she is actually a member and the chair) has come out with her own budget proposal. Now one or more members of the council have their backs up, writing blogs and making statements about being stabbed in the back. In all of this, there hasn’t been a lot of “falling on one’s face” going on. ~ The incident described in the Book of Numbers was really all about Korah’s personal grievances, suitably disguised for public consumption. Moses could have fired right back at him. But Moses suspected that his own earlier mistakes might be the cause of Korah’s uprising, that it was his failure which had created a setting in which discontent could germinate and ultimately promote the Levite rebellion. So, in humility, Moses admits accountability. Might a little of Moses’ humility be a good idea for the current crop of spiritual leadership? ~ Several church members recently have written blogs analyzing the budget and the business of the up-coming General Convention. Would that the Episcopal Church’s bishops, Executive Council, Presiding Bishop, deputies to General Convention, et al. would read these and consider their own roll in creating the situation in which the church finds itself. But I’m afraid they are too busy pointing the finger at one another, blind-siding one another, accusing one another of stabs in the back, playing turf wars, and engaging in cat-fights and pissing-contests. ~ We could use a little less of that sort of thing and a lot more falling on faces!

Moses “fell on his face.” This is biblical language for expressing great despair and sadness, not the reaction to a leadership confrontation a modern person would expect. Anger? Yes. Hostility? Yes. Yelling and shouting and public protestation of one’s rightness? Yes. Falling prostrate on the ground in desperate sadness? Not so much. ~ It would appear that in the confrontation of Korah and his compatriots, Moses felt personal responsibility. He believe that what had gone wrong with the Hebrews was his fault. He seems to have believed that he himself had created an atmosphere which had led to less-than-perfect delegated administration and justice. ~ Unfortunately a leadership crisis in the Episcopal Church isn’t resulting in similar behavior from the church’s leadership. In recent months the two highest officials of the church (the Presiding Bishop and the President of the House of Deputies) have had a public squabble over when and how one or the other might communicate with other persons in the church (the cause of the dispute was a video the PB made and sent to members of the House of Deputies, apparently without a “heads-up” to the PHoD). More recently, proposals for the church’s budget for the coming triennium have raised concern among many church members. In response to the first criticisms, the Executive Council issued a statement which was wholey inadequate (in my opinion) and failed to take responsibility. Then the PB (apparently distancing herself from the Executive Council of which she is actually a member and the chair) has come out with her own budget proposal. Now one or more members of the council have their backs up, writing blogs and making statements about being stabbed in the back. In all of this, there hasn’t been a lot of “falling on one’s face” going on. ~ The incident described in the Book of Numbers was really all about Korah’s personal grievances, suitably disguised for public consumption. Moses could have fired right back at him. But Moses suspected that his own earlier mistakes might be the cause of Korah’s uprising, that it was his failure which had created a setting in which discontent could germinate and ultimately promote the Levite rebellion. So, in humility, Moses admits accountability. Might a little of Moses’ humility be a good idea for the current crop of spiritual leadership? ~ Several church members recently have written blogs analyzing the budget and the business of the up-coming General Convention. Would that the Episcopal Church’s bishops, Executive Council, Presiding Bishop, deputies to General Convention, et al. would read these and consider their own roll in creating the situation in which the church finds itself. But I’m afraid they are too busy pointing the finger at one another, blind-siding one another, accusing one another of stabs in the back, playing turf wars, and engaging in cat-fights and pissing-contests. ~ We could use a little less of that sort of thing and a lot more falling on faces! This psalm is not the only time Holy Scripture reports God’s displeasure with the sacrifice of animals. Consider these words from the first chapter of the Book of Isaiah, “What to me is the multitude of your sacrifices? says the Lord; I have had enough of burnt offerings of rams and the fat of fed beasts; I do not delight in the blood of bulls, or of lambs, or of goats. When you come to appear before me, who asked this from your hand? Trample my courts no more; bringing offerings is futile; incense is an abomination to me. New moon and sabbath and calling of convocation – I cannot endure solemn assemblies with iniquity.” (Isa. 1:11-13) Despite all of the ritual directions found in the Law and in the Histories (see, e.g., Exodus 29, Leviticus 1, Numbers 7, and 1 Kings 18), the Psalmist, the first Isaiah, and especially the Prophet Micah make it very clear that sacrificing innocent animals is not what Judaism (or religion in general) is all about. Micah writes, “‘With what shall I come before the Lord, and bow myself before God on high? Shall I come before him with burnt offerings, with calves a year old? Will the Lord be pleased with thousands of rams, with ten thousands of rivers of oil? Shall I give my firstborn for my transgression, the fruit of my body for the sin of my soul?’ He has told you, O mortal, what is good; and what does the Lord require of you but to do justice, and to love kindness, and to walk humbly with your God?” (Micah 6:6-8) It may be that doing justice, loving kindness, and walking with God may (and often does) require one to give up one’s possessions, one’s livelihood, even one’s life. But such “sacrifice” without the demanded ethical basis, sacrifice done only to curry favor with God, is not what God asks or wants. ~ It is from this ethical stream in ancient Judaism that Christianity flows. It is unfortunate that early Christian writers looked back to the sacrificial practices of the Temple to find an analog to crucifixion of Jesus; we might have seen the Christian religion develop differently if, like the writers of the Gospels, they had looked more to the prophets. Jesus certainly did: “‘You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your mind.’ This is the greatest and first commandment. And a second is like it: ‘You shall love your neighbor as yourself.’ On these two commandments hang all the law and the prophets.” (Matthew 22:37-40) ~ So spare that bull! Sacrifices of animals (or their modern analogs, whatever they may be) are not the sacrifices that demonstrate love of God and love of neighbor. Rather, the core of ethical religion is as the writer of the Letter to Hebrews said: “Do not neglect to do good and to share what you have, for such sacrifices are pleasing to God.” (Heb. 13:16)

This psalm is not the only time Holy Scripture reports God’s displeasure with the sacrifice of animals. Consider these words from the first chapter of the Book of Isaiah, “What to me is the multitude of your sacrifices? says the Lord; I have had enough of burnt offerings of rams and the fat of fed beasts; I do not delight in the blood of bulls, or of lambs, or of goats. When you come to appear before me, who asked this from your hand? Trample my courts no more; bringing offerings is futile; incense is an abomination to me. New moon and sabbath and calling of convocation – I cannot endure solemn assemblies with iniquity.” (Isa. 1:11-13) Despite all of the ritual directions found in the Law and in the Histories (see, e.g., Exodus 29, Leviticus 1, Numbers 7, and 1 Kings 18), the Psalmist, the first Isaiah, and especially the Prophet Micah make it very clear that sacrificing innocent animals is not what Judaism (or religion in general) is all about. Micah writes, “‘With what shall I come before the Lord, and bow myself before God on high? Shall I come before him with burnt offerings, with calves a year old? Will the Lord be pleased with thousands of rams, with ten thousands of rivers of oil? Shall I give my firstborn for my transgression, the fruit of my body for the sin of my soul?’ He has told you, O mortal, what is good; and what does the Lord require of you but to do justice, and to love kindness, and to walk humbly with your God?” (Micah 6:6-8) It may be that doing justice, loving kindness, and walking with God may (and often does) require one to give up one’s possessions, one’s livelihood, even one’s life. But such “sacrifice” without the demanded ethical basis, sacrifice done only to curry favor with God, is not what God asks or wants. ~ It is from this ethical stream in ancient Judaism that Christianity flows. It is unfortunate that early Christian writers looked back to the sacrificial practices of the Temple to find an analog to crucifixion of Jesus; we might have seen the Christian religion develop differently if, like the writers of the Gospels, they had looked more to the prophets. Jesus certainly did: “‘You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your mind.’ This is the greatest and first commandment. And a second is like it: ‘You shall love your neighbor as yourself.’ On these two commandments hang all the law and the prophets.” (Matthew 22:37-40) ~ So spare that bull! Sacrifices of animals (or their modern analogs, whatever they may be) are not the sacrifices that demonstrate love of God and love of neighbor. Rather, the core of ethical religion is as the writer of the Letter to Hebrews said: “Do not neglect to do good and to share what you have, for such sacrifices are pleasing to God.” (Heb. 13:16) The simple answer is that fasting is going without some or all food or drink or both for a defined period of time. An absolute fast is abstinence from all food and liquid for a period of at least one day, sometimes for several days. Other fasts may be only partially restrictive, limiting particular foods or substance. The fast may also be intermittent in nature; for example, Muslims fast during the daylight hours of the month of Ramadan which is intended to teach Muslims patience, spirituality, humility, and submissiveness to God. Fasting as a spiritual practice is common to all major religions. Mahatma Gandhi once noted:

The simple answer is that fasting is going without some or all food or drink or both for a defined period of time. An absolute fast is abstinence from all food and liquid for a period of at least one day, sometimes for several days. Other fasts may be only partially restrictive, limiting particular foods or substance. The fast may also be intermittent in nature; for example, Muslims fast during the daylight hours of the month of Ramadan which is intended to teach Muslims patience, spirituality, humility, and submissiveness to God. Fasting as a spiritual practice is common to all major religions. Mahatma Gandhi once noted: