====================

A homily offered by the Rev. Dr. C. Eric Funston at the Festival Eucharist of the Resurrection on Easter Sunday, April 16, 2017, to the people of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Medina, Ohio, where Fr. Funston is rector.

(The lessons for the service are from the Revised Common Lectionary: Jeremiah 31:1-6; Colossians 3:1-4; Psalm 118:1-2,14-24, and St. Matthew 28:1-10. These lessons can be read at The Lectionary Page.)

====================

Make no mistake: if He rose at all

it was as His body;

if the cells’ dissolution did not reverse, the molecules

reknit, the amino acids rekindle,

the Church will fall.

It was not as the flowers,

each soft Spring recurrent;

it was not as His Spirit in the mouths and fuddled

eyes of the eleven apostles;

it was as His Flesh: ours.

The same hinged thumbs and toes,

the same valved heart

that – pierced – died, withered, paused, and then

regathered out of enduring Might

new strength to enclose.

Let us not mock God with metaphor,

analogy, sidestepping transcendence;

making of the event a parable, a sign painted in the

faded credulity of earlier ages:

let us walk through the door.

The stone is rolled back, not papier-mache,

not a stone in a story,

but the vast rock of materiality that in the slow

grinding of time will eclipse for each of us

the wide light of day.

And if we will have an angel at the tomb,

make it a real angel,

weighty with Max Planck’s quanta, vivid with hair,

opaque in the dawn light, robed in real linen

spun on a definite loom.

Let us not seek to make it less monstrous,

for our own convenience, our own sense of beauty,

lest, awakened in one unthinkable hour, we are

embarrassed by the miracle,

and crushed by remonstrance.

I love that poem, John Updike’s Seven Stanzas at Easter from the collection Telephone Poles and Other Poems. I have read it here before and, doubtless, I will read it again.

Only a poet like Updike could use the word monstrous to describe the Resurrection of Christ and, in spite of its shock value, or perhaps because of it, it is the perfect word, an ambiguous word that captures the essence of the entire Triumphal Entry – Passover Supper – Crucifixion – Resurrection event, the three-act drama of redemption which we began to remember on Palm Sunday.

Monstrous can, and usually does, mean something like “frightful or hideous; extremely ugly; shocking or revolting; awful or horrible,” and those are certainly good words to describe the way the people of Jerusalem turned on Jesus, the way his disciple Judas betrayed him, the way his other followers denied and abandoned him, the way the authorities, both Jewish and Roman, abused and killed him, mocking, scourging, and finally crucifying him. It was all monstrous; there’s no doubt about that!

Monstrous, however, can also mean “extraordinarily great; huge; immense; outrageous; overwhelming.” And those are superlative ways to describe the fact of Christ’s Resurrection from the dead! It is a huge thing! It is immense, outrageous, overwhelming! Yes, the Resurrection is monstrous!

There are two people who are hardly ever thought of in all of this three-part drama, in all the majesty of Holy Week and Easter: one of them is mentioned briefly only by John in his story of Jesus’ Crucifixion; the other isn’t named at all. I refer to Mary and Joseph, Jesus’ mother and foster father.

Of course, we know nothing of Joseph during Jesus’ adult ministry; after that event in the Jerusalem Temple when Jesus was about 13, Joseph is never again mentioned in the Gospels. Some suppose this is because he had passed away, but I like to think that he was just back home in Nazareth working the family business, doing carpentry or carving stone, making tables and chairs or building homes, keeping the family provided for so that Jesus could go about his ministry and Mary could accompany him.

Mary is mentioned in John’s story of the Crucifixion as standing at the foot of the cross and being entrusted by Jesus to the disciple whom he loved. And the legend from which we get the 14th Station of the Cross and Michelangelo’s exquisitely beautiful Pieta is that when his body was removed from the cross she held him, dead, in her arms. But there is no mention of her or of Joseph at Jesus’ burial, nor are they mentioned in any of the accounts of Christ’s post-resurrection appearances.

That omission, for I am sure that is what it is, an omission, disturbs me. Two weeks ago was the 59th anniversary of my father’s death at the age of 39. I am now about the age his mother and father, my grandparents, were when he died. One of my clearest memories of childhood is his funeral. I remember how, as we were leaving the graveside, my grandparents hung back, how they could not step away from nor turn their backs on the grave that held their child’s lifeless body. When, at last, they accepted my Uncle Scott’s physical encouragement to do so, my grandmother said to my mother, “A mother should not outlive her child.” She would know that feeling again just a few years later when my Uncle Scott died of cancer.

And own my mother would know it, as well, when in 1993 my only sibling, my older brother Rick, died of brain cancer. I vividly remember doing exactly what my uncle had done, physically moving my mother and stepfather away from the grave, the grave they could not leave on their own. Later that day, my mother said to me, “You’re grandmother was right. A parent should not outlive her child.”

Having seen my grandparents and my parents at the graves of their children, I cannot believe that Mary and Joseph were not there when the stone was rolled into place, when Jesus was buried in that borrowed tomb.

Updike’s portrayal of the Resurrection and his admonition to us, “Let us not seek to make it less monstrous,” so aptly describe the entire event of Holy Week and Easter, because we cannot appreciate the overwhelming wonder of the Resurrection, this third act of the redemption drama, without taking into account the first two acts, all of the horror and ugliness they portrayed: Judas’ betrayal, the other disciples abandonment, Peter’s denial, the trial before Pilate, Christ’s scourging and humiliation, his bitter agony on the Cross, his final self-emptying in death, and his burial. It is all monstrous; painful and ugly and awful in the first sense of that wonderfully ambiguous adjective. And I cannot believe that his parents were not there, did not experience the whole monstrous lot of it!

And, just as I am puzzled by the absence of almost any mention of Mary and Joseph in the narrative of Christ’s death and burial, and I am astounded that there is no allusion to them in the Gospel accounts of that first Easter morning or any time after his Resurrection! The only word about either of them is in the first chapter of the Book of Acts and, again, it’s only Mary who gets mentioned. Luke, the author of Acts, says that following Christ’s Ascension forty days after his Resurrection the apostles “were constantly devoting themselves to prayer, together with certain women, including Mary the mother of Jesus, as well as his brothers.” (Acts 1:14) That’s it, that one mention! I find that astonishing!

Apparently so have many Christians throughout the ages, because there is an extra-biblical tradition that the Virgin Mary was the first person to witness our Lord’s Resurrection. The Golden Legend, a medieval collection of stories about the saints, says that the first appearance of the resurrected Christ on Easter Day was to the Virgin Mary:

It is believed to have taken place before all the others, although the evangelists say nothing about it.. . . . [I]f this is not to be believed, on the ground that no evangelist testifies to it . . . perish the thought that such a son would fail to honor such a mother by being so negligent! . . . Christ must first of all have made his mother happy over his resurrection, since she certainly grieved over his death more than the others. He would not have neglected his mother while he hastened to console others.

St. Ignatius of Antioch (1st C.) claimed it was so, as did St. Ambrose of Milan (4th C.), St. Paulinus of Nola (4th C.), the poet Sedulius (5th C.), St. Anselm of Canterbury (11th C.), St. Albertus Magnus (13th C.), St. Bernardino da Siena (15th C.), and the bible scholar Juan Maldonado (16th C.) More recently, the late Pope John Paul II, in 1997 expressed his opinion that Mary “was probably the first person to whom the risen Jesus appeared.” (Gen. Aud., Wednesday, 21 May 1997)

We live through this three-act drama every year in a set series of events: triumphal entry on Palm Sunday, last supper and then the prayers at Gethsemane on Maundy Thursday, the crucifixion on Good Friday, weeping at the tomb on Holy Saturday, and then – of course – our liturgy and our hymns encourage us to express joy on Easter morning. In Matthew’s Gospel we are told that Mary Magdalene and the other Mary ran from the tomb “with fear and great joy,” but in our reading this morning from John a weeping Mary Magdalene, upon recognizing her risen teacher, literally clings to his feet in prostrate relieve; I wonder if that might have been the more common reaction of Jesus’ disciples and parents.

I believe that the legends and early fathers and the late pope are right, that the Risen Christ appeared to Mary and Joseph, as well as and probably before the eleven apostles and their friends, and that they would have been profoundly shaken, perhaps overwhelmingly frightened, and maybe eventually greatly reassured. But I’m not so sure that joy would be the best description of their initial reaction; perhaps the closest they might have come would have been relief.

We remember the three-act drama, as I said, in an orderly fashion. But if we know one thing about human beings, it is that we are not orderly creatures.

It may seem odd, but in just a few days, the Daily Office Lectionary will put us back to the beginning of Lent. At the end of the second week of Easter this year, the Daily Office gospel reading will be about Jesus’ temptations in the desert following his baptism.

That’s not odd, at all, really. Our spiritual life, like our emotional life, follows no particular schedule, no orderly progression. Elizabeth Kubler-Ross outlined five stages of grief – denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance – and people often think they follow an orderly progression, just like our Holy Week and Easter celebrations. But clinical experience has shown that a grieving person does not move neatly through them as if they were rungs on a ladder. One may move from denial to anger to bargaining and then return to denial; one may skip a stage only to return to it later; one may spend a good deal of time in one stage and only a short while in another. There is no orderly progression and I can well imagine that Mary and Joseph and the apostles and the women at the tomb were all experiencing that sort of emotional bouncing about, an emotional roller coaster the like of which probably none of us have ever known.

Our spiritual lives are the same. As one works through the process of enlightenment, of salvation, of spiritual growth, of whatever-one-calls-it, one does not follow a schedule. We may move back to an earlier stage, revisit issues we thought we’d dealt with.

St. Paul urged his friends in the church at Caesarea Philippi to “work out your own salvation with fear and trembling; for it is God who is at work in you, enabling you both to will and to work for his good pleasure.” (Philip. 2:12-13) Nowhere does Scripture promise that this work will be neat and tidy. If anything, the witness of Scripture is that spiritual and emotional growth is a messy affair.

That is why I suggest that the closest the first witnesses to Jesus’ Resurrection might have come to joy would perhaps better be described as relief. The dictionary defines relief as “alleviation of pain, as the easing of anxiety, as deliverance from distress.” This is an appropriate experience and emotion for Easter Day, profound relief.

I think the joy comes later in the Easter Season and that it comes later in life as we live out our Easter faith. But in the immediate aftermath of the monstrous-ness of Holy Week, here in the third act of the drama of redemption, in the wake of the horrible ugliness of betrayal and death that occurred in the first two acts, one may simply not be ready to be jubilant and happy. In the face of our own sinfulness and spiritual dysfunction, in the reality of our own messy spiritual lives, we may not be ready for joy and gladness. But the fact of Christ’s Resurrection relieves us of grief and sorrow; it relieves us of sin and death.

The experience and impact of Easter Day is one of profound, overwhelming, (one might even say) monstrous relief.

Perhaps that is why Jesus stuck around for forty days, to continually reassure and sustain the disciples in their relief from fear and sorrow and grief, so that they could move into joy and gladness as time went on. Perhaps that is why in producing the third act of the drama of redemption the church offers not a single day, but a season of fifty days, so that as it progresses we can . . . like Mary and Joseph, like Peter and the disciple whom Jesus loved, like all the apostles . . . move from shock into relief, from relief into joy, so that it provides a pattern with which we can handle the inevitable losses in our lives.

As life goes on and as the victory of life over death sinks in, Easter relief will grow into Easter joy, something that propels us toward action and compels us to invite others into the Resurrected life of our Risen Lord. As Christians, we have access through the relief of Christ’s Resurrection into a joy that is unshakable – for joy is really not an emotion; it is a virtue. Easter joy does not mean being happy all the time or being fine when times are difficult; Easter joy means being sustained by the power of the Resurrection.

What Easter means is that in the depths of our being, despite the circumstances we may face, despite any fears we may have, despite whatever may be tearing up our souls, despite whatever sin or spiritual malaise we may be suffering, despite whatever disorderly messes our spiritual lives may be in, we are able to get through them, to let go of them, and to find relief and eternal life in the Resurrected Christ, a life into which we invite others.

John tells us that on that first Easter morning, when Mary Magdalen fell at her Risen Lord’s feet, he admonished her, “Do not hold on to me; I am ascending to my Father.” It doesn’t sound to me like this woman who had just been grieving at his tomb was expressing joy, nor that Jesus’ was encouraging it. What I hear is Jesus offering comfort and relief.

It has been said that joy comes from letting go – letting go of our attachments, letting go of any thoughts that the present moment should or even could be different than it is, letting go of our expectations. Joy is the virtue of celebrating the present, of living in the moment, something to which we come through a process of detachment and release, something that we like Mary Magdalene let go of the old Jesus, the Jesus who died on the cross, and follow the now-Risen and ascended Jesus, “the pioneer and perfecter of our faith, who for the sake of the joy that was set before him endured the cross, disregarding its shame, and has taken his seat at the right hand of the throne of God.” (Heb. 12:2)

Resurrection Day is not the end of the process; it is the beginning. “Do not be afraid,” Jesus said to Mary Magdalen. In John’s Gospel, Jesus tells her not to hang on to him. In both gospels the message is, “Let go” – let go of me, let go of your fear.

Easter Day brings relief, overwhelming relief! Through that relief we are able to let go, to release our fears, our griefs, our worries, and our sorrows with absolute abandon, to be completely freed of our sinfulness! In letting go as the Easter Season and as our Easter faith progress, we are able to work out our salvation, for it is God who is at work in us, and ultimately find joy, unutterably ecstatic joy, huge, overwhelming, outrageous joy into which we are compelled to invite others!

Make no mistake: if He rose at all

it was as His body . . .

Let us not seek to make it less monstrous!

Alleluia! Christ is risen!

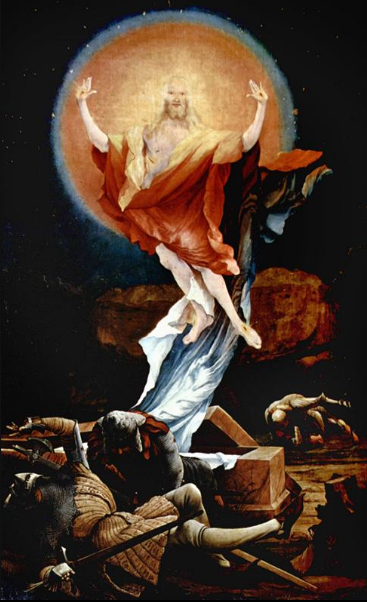

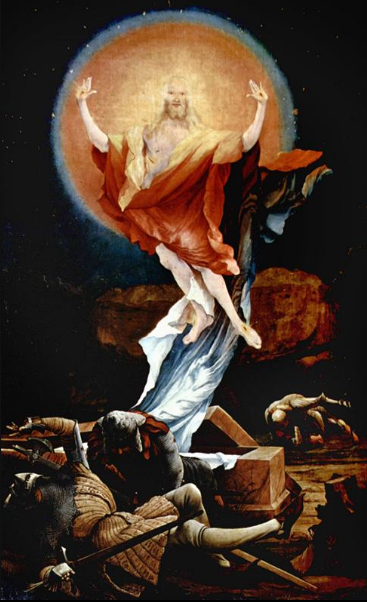

(The illustration is The Resurrection Of Christ (Right Wing Of The Isenheim Altarpiece) by Matthias Grünewald, c.1512–16)

====================

Father Funston is the rector of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Medina, Ohio.

Like many (perhaps most) Episcopal churches, my first congregation had a set of large red doors on the front of their building. But also like many Episcopal churches, no one ever used them because all the members knew how to enter through a more convenient door near the parking lot.

Like many (perhaps most) Episcopal churches, my first congregation had a set of large red doors on the front of their building. But also like many Episcopal churches, no one ever used them because all the members knew how to enter through a more convenient door near the parking lot.

Two weeks ago, the Sunday lectionary treated us to the entire long Gospel lesson of the story of Jesus’ raising of Lazarus and then last week the Daily Office lectionary repeated it in smaller bits over the course of several days. Last Sunday I suggested that Holy Week and Easter can be conceived as a three-act drama to which the Triumphal Entry of Palm Sunday is an overture.

Two weeks ago, the Sunday lectionary treated us to the entire long Gospel lesson of the story of Jesus’ raising of Lazarus and then last week the Daily Office lectionary repeated it in smaller bits over the course of several days. Last Sunday I suggested that Holy Week and Easter can be conceived as a three-act drama to which the Triumphal Entry of Palm Sunday is an overture.

On Palm Sunday, I suggested that we think of Holy Week and Easter as a three-act drama beginning with an Overture on Palm Sunday. Last night, we took part in the first act. The analogy of the Three Holy Days (or “Triduum”) to a play breaks down if we think of ourselves as the “audience.” We are not the audience.

On Palm Sunday, I suggested that we think of Holy Week and Easter as a three-act drama beginning with an Overture on Palm Sunday. Last night, we took part in the first act. The analogy of the Three Holy Days (or “Triduum”) to a play breaks down if we think of ourselves as the “audience.” We are not the audience. On Palm Sunday, I suggested that we think of Holy Week and Easter as a three-act drama beginning with an Overture on Palm Sunday. Today, we take part in the first act. The analogy of the Three Holy Days (or “Triduum”) to a play breaks down if we think of ourselves as the “audience.” We are not the audience.

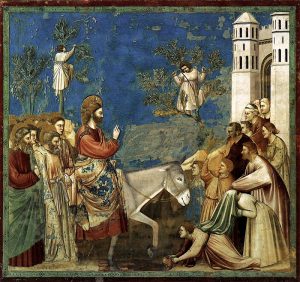

On Palm Sunday, I suggested that we think of Holy Week and Easter as a three-act drama beginning with an Overture on Palm Sunday. Today, we take part in the first act. The analogy of the Three Holy Days (or “Triduum”) to a play breaks down if we think of ourselves as the “audience.” We are not the audience.  Redemption is a drama in three acts – three acts and a brief intermission – today the prelude, the overture, an introduction encapsulating the story to be fleshed out as the action proceeds. Jesus and his companions enter the city of Jerusalem from the east while the Roman governor, Pilate, makes his annual procession into the city in pomp and circumstance from the west.

Redemption is a drama in three acts – three acts and a brief intermission – today the prelude, the overture, an introduction encapsulating the story to be fleshed out as the action proceeds. Jesus and his companions enter the city of Jerusalem from the east while the Roman governor, Pilate, makes his annual procession into the city in pomp and circumstance from the west.  Today the lectionary gives us two stories about water. The first set in the Sinai desert where the Hebrews found themselves exhausted, thirsty, and more than a little bit feisty and quarrelsome demanding water from Moses and from God; the second set at a well in a Samaritan village where Jesus, “tired out by his journey” (Jn 4:6, NRSV), encountered a lone woman and asked her for a drink.

Today the lectionary gives us two stories about water. The first set in the Sinai desert where the Hebrews found themselves exhausted, thirsty, and more than a little bit feisty and quarrelsome demanding water from Moses and from God; the second set at a well in a Samaritan village where Jesus, “tired out by his journey” (Jn 4:6, NRSV), encountered a lone woman and asked her for a drink. When I was child in my tween years, I spent a lot of time at the Public Library checking out stacks of books, with that wonderful musty library smell, to read under the big oak tree in our back yard on hot summer days. As I was a U.S. history buff both then and now, I gravitated toward a series of children’s books whose titles began with the phrase – “we were there”. For example, We Were There at Lexington and Concord, We Were There at Battle of Gettysburg and my favorite – We Were There at Pearl Harbor. The books had the same two characters – a boy and a girl around my age at the time, who happened to be living right in the middle of these key historic events. They often performed semi-heroic acts and were usually honored or congratulated by some famous person at the end of the book.

When I was child in my tween years, I spent a lot of time at the Public Library checking out stacks of books, with that wonderful musty library smell, to read under the big oak tree in our back yard on hot summer days. As I was a U.S. history buff both then and now, I gravitated toward a series of children’s books whose titles began with the phrase – “we were there”. For example, We Were There at Lexington and Concord, We Were There at Battle of Gettysburg and my favorite – We Were There at Pearl Harbor. The books had the same two characters – a boy and a girl around my age at the time, who happened to be living right in the middle of these key historic events. They often performed semi-heroic acts and were usually honored or congratulated by some famous person at the end of the book.  The First Sunday in Lent … that’s today. That means we get the story of Jesus being chased into the desert by the Holy Spirit after his baptism by John in the River Jordan, the story of Jesus being accosted in the desert by the Tempter (whom Matthew in our Gospel text today also names “the devil” – in Greek the word is diabolos meaning “accuser”), the story of Jesus refusing to give into the three temptations. We always get some version of this story on the First Sunday in Lent. And this year the Lectionary gives us a double-whammy of temptation by linking that familiar gospel tale with the equally family story of Eve and the serpent and the fruit of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, the so-called “apple.”

The First Sunday in Lent … that’s today. That means we get the story of Jesus being chased into the desert by the Holy Spirit after his baptism by John in the River Jordan, the story of Jesus being accosted in the desert by the Tempter (whom Matthew in our Gospel text today also names “the devil” – in Greek the word is diabolos meaning “accuser”), the story of Jesus refusing to give into the three temptations. We always get some version of this story on the First Sunday in Lent. And this year the Lectionary gives us a double-whammy of temptation by linking that familiar gospel tale with the equally family story of Eve and the serpent and the fruit of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, the so-called “apple.”