From the Book of Exodus:

Amalek came and fought with Israel at Rephidim. Moses said to Joshua, “Choose some men for us and go out; fight with Amalek. Tomorrow I will stand on the top of the hill with the staff of God in my hand.” So Joshua did as Moses told him, and fought with Amalek, while Moses, Aaron, and Hur went up to the top of the hill. Whenever Moses held up his hand, Israel prevailed; and whenever he lowered his hand, Amalek prevailed. But Moses’ hands grew weary; so they took a stone and put it under him, and he sat on it. Aaron and Hur held up his hands, one on one side, and the other on the other side; so his hands were steady until the sun set. And Joshua defeated Amalek and his people with the sword.

(From the Daily Office Lectionary – Exodus 17:8-13 (NRSV) – May 3, 2014.)

At first blush, this just feels like another unbelievable story of religious ritual and “magic hands.” It fits neatly into the pattern of war stories one finds in the Torah that are attributed to the Deuteronomist. For that writer, the Hebrews’ victory in battle always depends not on military preparation, strength of arms, or fighting skill, but on ritual exactitude — perform a religious ritual properly and you win, flub it and you lose.

At first blush, this just feels like another unbelievable story of religious ritual and “magic hands.” It fits neatly into the pattern of war stories one finds in the Torah that are attributed to the Deuteronomist. For that writer, the Hebrews’ victory in battle always depends not on military preparation, strength of arms, or fighting skill, but on ritual exactitude — perform a religious ritual properly and you win, flub it and you lose.

I recall reading rabbinic commentary, however, that puts a different spin on the story. According to the rabbis, there was nothing “magic” or even particularly noteworthy about Moses’ hands; they were simply a reminder to the Hebrew fighters below to put their faith in God. When they looked up to see Moses’ hands raised, they looked to heaven, trusted in God, and prevailed; when his hands were down, they failed to do so.

When I was in seminary, there was a practicum in liturgics, basically a class on how to do the ritual of the Eucharist. We called it “magic hands.” Our instructor, Dr. Louis Weil, repeatedly advised us to be aware of our hands, to be aware that the congregation would focus upon them and any movement we made, and therefore to make few gestures, but make every gesture one that would not distract the congregation from their worship. I am reminded of Dr. Weil’s instruction by this story.

I’m also mindful that Moses didn’t do this alone. If Aaron and Hur hadn’t been there to hold up Moses’ hands, whether “magic” in themselves or simply a motivational banner to the warriors, the battle would have gone otherwise. The story is a reminder of the importance of community and, for community leaders, of the importance of those with whom they work. No one does the task of leadership alone.

This, too, reminds me of the tradition of the Eucharist that holds that a priest alone cannot say the Mass; he or she must be accompanied by at least one other person: Jesus said, “Where two or three are gathered in my name, I am there among them.” (Mt 18:20) I am told that in some Orthodox traditions, there must be, in addition to the priest, at least one deacon and one lay person so that the fullness of the church is represented. (That would be impossible in my congregation; as much as I would like to have a vocational deacon or two in our midst, there is none.)

So I think this is a story of more than “magic hands,” more than a story of winning through proper religious ritual. If there is any magic in the hands of leaders, it is found in both the power to which those hands point and in the support on which those hands depend.

====================

A request to my readers: I’m trying to build the readership of this blog and I’d very much appreciate your help in doing so. If you find something here that is of value, please share it with others. If you are on Facebook, “like” the posts on your page so others can see them. If you are following me on Twitter, please “retweet” the notices of these meditations. If you have a blog of your own, please include mine in your links (a favor I will gladly reciprocate). Many thanks!

====================

Father Funston is the rector of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Medina, Ohio.

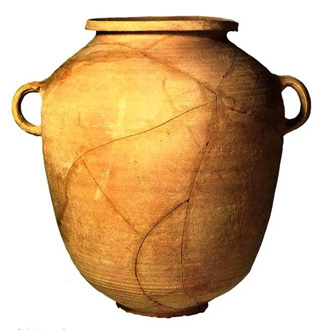

An ephah is a bushel, about 35 liters. Ten ephahs make a homer; a tenth of an ephah is an omer. (I’ll bet that was sometimes confusing.) So an omer is 3.5 liters, just a little bit shy of a gallon.

An ephah is a bushel, about 35 liters. Ten ephahs make a homer; a tenth of an ephah is an omer. (I’ll bet that was sometimes confusing.) So an omer is 3.5 liters, just a little bit shy of a gallon. Two days ago we celebrated the Feast of St. Mark the Evangelist and the Gospel lesson for use at the Eucharist was the opening of his Gospel which relates the story of Jesus’ baptism following which, Mark says, “the Spirit immediately drove him out into the wilderness,” (Mk 1:12) so the word “wilderness” caught my attention today.

Two days ago we celebrated the Feast of St. Mark the Evangelist and the Gospel lesson for use at the Eucharist was the opening of his Gospel which relates the story of Jesus’ baptism following which, Mark says, “the Spirit immediately drove him out into the wilderness,” (Mk 1:12) so the word “wilderness” caught my attention today. I am given to hyperbole. I know that. So, apparently, was David (the superscript to this psalm attributes it to David), as the first verse of today’s evening psalm amply demonstrates. I’ll bet he got into as much trouble (or maybe more) because of that as I get into!

I am given to hyperbole. I know that. So, apparently, was David (the superscript to this psalm attributes it to David), as the first verse of today’s evening psalm amply demonstrates. I’ll bet he got into as much trouble (or maybe more) because of that as I get into! My mind really isn’t on the scriptures this morning . . . except this idea of being informed of something before it occurs, so that when it does occur, one will be ready to accept it.

My mind really isn’t on the scriptures this morning . . . except this idea of being informed of something before it occurs, so that when it does occur, one will be ready to accept it. I think Jesus is being a little rough on Philip. Granted, Jesus has done everything possible during his ministry to make the Father known, to be transparent to those around him, to reveal as much of himself as he can. Still, it is possible to be with someone for years and still not know them.

I think Jesus is being a little rough on Philip. Granted, Jesus has done everything possible during his ministry to make the Father known, to be transparent to those around him, to reveal as much of himself as he can. Still, it is possible to be with someone for years and still not know them. “Better the devil you know than the devil you don’t know,” was something my grandmother often said. Apparently she took after the ancient Israelites . . . but then don’t most people. We would rather stay in (or return to) a bad situation than face a possibly worse predicament. God know these people well — not too much farther down the road they will complain about their hunger and long for the pots of stew they enjoyed as slaves:

“Better the devil you know than the devil you don’t know,” was something my grandmother often said. Apparently she took after the ancient Israelites . . . but then don’t most people. We would rather stay in (or return to) a bad situation than face a possibly worse predicament. God know these people well — not too much farther down the road they will complain about their hunger and long for the pots of stew they enjoyed as slaves: Psalm 136 is twenty-six verses long. The second half of every single verse is the same: “For [God’s] steadfast love endures for ever.”

Psalm 136 is twenty-six verses long. The second half of every single verse is the same: “For [God’s] steadfast love endures for ever.”  I think I know what Paul is trying to say here, but I don’t like the way he’s saying it. I mean, I really have a theological issue with the assertion that “flesh and blood cannot inherit the kingdom of God.” I think the statement is just plain wrong. It states a dualism that relegates the material, specifically the human body, to realm of the damned, the unclean, the unworthy. In light of a creation story in which the Creator “saw everything that he had made [including that human flesh and blood], and indeed, it was very good,” I cannot accept the condemnation of our material being.

I think I know what Paul is trying to say here, but I don’t like the way he’s saying it. I mean, I really have a theological issue with the assertion that “flesh and blood cannot inherit the kingdom of God.” I think the statement is just plain wrong. It states a dualism that relegates the material, specifically the human body, to realm of the damned, the unclean, the unworthy. In light of a creation story in which the Creator “saw everything that he had made [including that human flesh and blood], and indeed, it was very good,” I cannot accept the condemnation of our material being. Twice in Easter week this story of the Jewish Temple authorities bribing the Roman soldiers to get them to say the followers of Jesus had stolen Jesus’ body is found in the lectionary. It is here in the Prayer Book’s Daily Office readings today; on Monday, it was the Eucharistic lectionary’s gospel lesson.

Twice in Easter week this story of the Jewish Temple authorities bribing the Roman soldiers to get them to say the followers of Jesus had stolen Jesus’ body is found in the lectionary. It is here in the Prayer Book’s Daily Office readings today; on Monday, it was the Eucharistic lectionary’s gospel lesson.