====================

This sermon was preached on the Third Sunday in Lent, March 23, 2014, at St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Medina, Ohio, where Fr. Funston is rector.

(The lessons for the day were: Exodus 17:1-7; Psalm 95; Romans 5:1-11; and John 4:5-42. These lessons can be read at The Lectionary Page.)

====================

Four interesting things happened this week. The first was our monthly Brown Bag Concert. During the construction of our Gallery addition to the Parish Hall, the attendance at the concerts had dropped off. Tuesday’s was the first since construction has been completed and we were unsure what sort of turn out we would see. Well, as it happened, we had over 100 people in this church for that concert! What a great thing!

Four interesting things happened this week. The first was our monthly Brown Bag Concert. During the construction of our Gallery addition to the Parish Hall, the attendance at the concerts had dropped off. Tuesday’s was the first since construction has been completed and we were unsure what sort of turn out we would see. Well, as it happened, we had over 100 people in this church for that concert! What a great thing!

The second thing was the death of Fred Phelps on Wednesday, March 19. The so-called Reverend Mr. Phelps was the so-called pastor of the so-called Westboro Baptist Church. I say “so-called” so many times because I believe Mr. Phelps was essentially self-ordained, and he founded the Westboro congregation which, despite its name, is not recognized by any national or regional Baptist convention. If you don’t recognize those names, Fred Phelps and his congregation are the people who show up with picket signs at the funerals of servicemen and other notable people, picket signs which read “God Hates [Homosexuals]” (only they use a much viler term on their signs). There’s a meme floating around the internet that reads, “Live your life in such a way that Fred Phelps will picket your funeral.” I recommend that.

In the days surrounding his death, my gay and lesbian friends were having quite a discussion of whether anyone should picket his funeral. Another Facebook meme answered that question: it was a cartoon of God saying, “I give you a new commandment: you shall not stoop to Fred Phelps’ level.” That’s where I came down on the question. We pray for the repose of Mr. Phelps’ soul, as we do for anyone who died; we pray that he find in death the peace he seemed not to find in life and which he denied to so many.

His death nearly coincided with what would have been the 86th birthday of another Fred, Fred Rogers, the man who assured children that everyday “it’s a beautiful day in the neighborhood.” What a contrast these two Freds present: the man who invited everyone to be his neighbor and the man who wanted almost no one to be his. I had a little vision when I heard of Fred Phelps’ death that he had arrived at the Pearly Gates to be greeted by Fred Rogers saying, “It’s a beautiful day in the neighborhood, Fred, and everybody’s here!”

The third thing was our “St. Patrick’s Last Gasp” Irish Festival yesterday. It was a great party and a smashing success. Ray and I were trying to figure out how many people actually attended and we think that, at the highest point, we probably had more than 250 people in this building – here in the church, in the parish hall, in the dining room – if we’d had 25% more people, we couldn’t have moved. That’s a great problem to have!

The fourth interesting thing that happened was that our diocesan communications office contacted me and asked if I would be one of seven Episcopal clergy in the Cleveland metropolitan area to answer some questions posed by the Cleveland Plain Dealer. “Sure,” I said and set about answering their questions. After doing so, I thought I ought to share my answers with you so you won’t be surprised when you open the paper someday soon and see what your rector is quoted as saying . . . because although their questions start innocently enough, they escalate rather quickly to address some thorny issues in our tradition and in our society.

I will get to addressing today’s Gospel lesson, trust me, but I want to share those answers with you first. So here they are . . . .

What is my favorite Easter tradition?

My favorite tradition is the Great Vigil of Easter celebrated as an evening service on Saturday evening or as a sunrise service on Resurrection Sunday. At St. Paul’s, Medina, we celebrate the Vigil in even numbered years on Resurrection Eve Saturday evening, and in odd numbered years on Sunday at sunrise. This year is our Saturday evening year and the service will begin after sundown at 8 p.m. Beginning the service in the dark with the lighting of the new fire, processing the Paschal Candle through the dark church, the church coming to light as other candles are lighted one from another, and finally the sanctuary fully lighted as the cry of “Alleluia! Christ is risen!” is sounded, the sun just rising (when we do it at sunrise), and the bells ringing . . . all of that brings me great joy. It speaks to me more clearly of the Light of Christ than any other tradition we observe at Easter or at any time during the church year. Of course, the Sunday morning Festival Eucharist (which will start at 10 a.m.) is great fun, as well!

How do I feel about the way Easter is celebrated in popular/secular culture?

I think the secular traditions of Easter (bunnies, eggs, new bonnets, a new set of dress clothes for the kids, lots of candy) are fine. They are celebrations of the new life of springtime. I’ve gotten out of the habit of calling our church celebration “Easter” and more often refer to it as “Resurrection Sunday” or “Resurrection Season,” so the term “Easter” actually speaks more to me of the secular festivities than of church observance, but the popular Easter traditions and the Christian celebration of Christ’s Resurrection all celebrate the joy of life returning. Human beings in all religious traditions (and those in none) have been celebrating springtime for millennia, and all that we do is good fun and spiritually uplifting. I don’t think the popular traditions detract from the religious significance at all.

What is the relationship between the Episcopal Church and the Anglican Communion (including the Church of England)?

The Episcopal Church is one of the many churches around the world which trace their lineage to Christ and the Apostles through the historic Church of England, a family of churches called “the Anglican Communion.” The U.S. Episcopal Church is the second such offshoot of the Church of England; the Scottish Episcopal Church, which ordained our first bishop, was the first. As Anglicans, we are a part of a reformed catholic tradition which separated from the Roman Catholic Church as a political act during the reign of England’s King Henry VIII, not as a result of theological reform or protest. The Episcopal Church is the only Anglican church in the United States officially recognized as such by the Archbishop of Canterbury, the Lambeth Conference, and the Anglican Consultative Council (our international “instruments of unity”).

What does it mean for the Episcopal Church to allow gay & lesbian weddings when the state of Ohio does not legally recognize these unions?

In considering this question, I think we should make a distinction between the civil contract of marriage, which is a creature of law defined by state statutes and constitutions, and the Sacrament of Holy Matrimony, which is the church’s blessing of a committed, loving relationship of two adult persons. Currently, the Episcopal Church does not offer this sacramental blessing to same-sex couples; we offer a service of blessing and life-long commitment. A study group has been appointed by our highest governing body, the General Convention, to reflect upon our theology of matrimony and make recommendations as to whether the sacrament can and should be extended to same-sex couples; I believe that it should.

Although state law (wrongly, in my opinion) currently denies same-sex couples the right to form the civil contract, that law cannot prohibit the church from offering its blessing to anyone or for any purpose; that would be a violation of the U.S. Constitution’s First Amendment. Therefore, the church is free to and does offer a service of blessing to couples who wish to make solemn vows of life-long commitment one to the other. The church’s blessing does not (and should not be understood to) constitute the formation of the legal contract of marriage. When in a traditional wedding ceremony the husband and wife make their promises, in the Episcopal Church, the first part of the service before the reading of Scripture and the making of the religious vows, is the formation of the contract; after that is done, Scripture is read, prayers are offered, and the religious vows are made and sanctified during the sacramental service of blessing.

By the way, I don’t like to use the term “gay wedding” or “lesbian wedding” because the wedding or commitment ceremony is just that, a ceremony, regardless of the gender or sexual orientations of the persons involved; the couple may be both of the same sex or of opposite sexes, but the nature of the commitments they make to each other in the religious vows — to rely upon God, to love and support one another, to care for each other, and so forth — are the same, neither gay nor lesbian nor straight.

What does “God loves you. No exceptions.” mean to me in a culture that’s spiritual but not religious or with little to no religious affiliation?

Well, I think the statement speaks for itself and would mean the same thing whether the surrounding culture were highly religious or completely secular; God’s love for everyone is not culture dependent. As a statement of belief of the Episcopal Church in this diocese, it means that everyone is welcome. As a former Presiding Bishop of our church once said, “There will be no outcasts in this church,” meaning no one is excluded from participating in our worship, our educational programs, or the social life of the church community. A few weeks ago we put up on our church sign this invitation: “You can belong before you believe.” There is welcome here for the “spiritual but not religious,” the unaffiliated, the disaffiliated, the questioner, the doubter . . . everyone. We don’t pretend to have all the answers, but we love exploring the questions and we offer a safe place for those with questions to do so. Although he’s not an Episcopalian, the author Brian McLaren speaks for our tradition when he writes in one of his books that the church should offer responses to questions, not answers; answers cut off conversation, while responses invite further discussion. The Episcopal Church offers responses. We think that’s what God does, too; God responds.

Considering the Gospel story of the Samaritan woman at Jacob’s well

Which brings us to today’s Gospel reading, a very long reading setting out the longest conversation Jesus has with anyone in any of the four Gospels. It’s amazing that Jesus had this conversation at all. First of all, he is speaking with a Samaritan. The Samaritans were the descendants of those who were left behind when the important families of Jerusalem and the country were taken into exile in Babylon. Those who got to stay in Israel had intermarried with the surrounding Canaanite peoples and continued to worship God according to the first four Books of Moses; they built a temple on Mt. Gerizim not far from the city of Sychar where this conversation took place and offered their sacrifices there. When the exiles returned and restored the temple in Jerusalem, they launched a campaign of “racial purity” demanding that those with “foreign” wives divorce them; adding the Book of Deuteronomy to the Scriptures, they also insisted that sacrifices could only be made at the Jerusalem temple. The Samaritans rejected these demands and “bad blood” existed between the two groups. By Jesus’ time, there was real hatred and enmity between them; John is a master of understatement when he says, “Jews do not share things in common with Samaritans.”

Not only was Jesus’ conversational partner a Samaritan, she was a woman! If we accept the Gospel’s naming of Jesus as a Rabbi, he was breaking all sorts of laws and traditions by conversing with a woman, even if she were a good and faithful Jew. Rabbis simply did not speak to any woman to whom they were not related; it just wasn’t done. And this particular woman, apart from being a Samaritan, was also a woman of (shall we say) besmirched reputation. She had been through five failed relationships and had entered into yet another with a man not her husband (how Jesus knows this I’m not sure, but he knows it).

So this poor woman was everything Jesus should have had nothing to do with, and yet there he is carrying on a conversation as if they were old friends. No wonder the disciples were astonished when they returned.

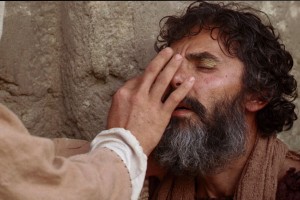

A fifth interesting thing happened this week. I was introduced to a Russian Orthodox icon depicting this Gospel story, and the interesting thing about it is that the icon writer chose to depict not only this story, but also the story of Zacchaeus. Zacchaeus, you remember, was the Jewish tax collector who climbed a tree so that he could get a look at Jesus as he walked through a crowd in the Jewish city of Jericho. (Luke 19:1-27) Just as with the woman at the well, Jesus spoke to Zacchaeus. And he didn’t just talk to him; he walked up to the tree and said, “Zacchaeus, come down because I’m going to have dinner with you.”

Now, Zacchaeus was a tax collector, a lacky of the hated Roman occupiers of Israel. We all, I’m sure, have our opinions of the agents of the I.R.S. and as we get closer to April 15, that opinion is probably going to get pretty bad. But whatever we may think of contemporary revenue agents, what the Jews thought of Jewish tax collectors was a thousand times worse. They were collaborators working with oppressive Roman Empire which had invaded and occupied the Jewish nation. They were given what was for practical purposes a license to steal. The Roman authorities would tell them what they were to collect, but they could take more and did; they excess was what they lived on. So they were as hated and as outcast among their own people as a Samaritan would have been.

I believe that is the reason the Russian iconographer depicted the two stories on the same panel; he was illustrating that for Jesus there were no outcasts. For God incarnate in Jesus, there are no outcasts. Despite what Fred Phelps may have taught in his church, the Gospel story we heard this morning and the story of Zacchaeus demonstrate that God hates no one. As that diocesan bumper sticker and billboard about which the Plain Dealer asked says, “God loves everyone. No exceptions.” In Christ’s church, in this church there will be no outcasts. Ever.

Amen.

====================

A request to my readers: I’m trying to build the readership of this blog and I’d very much appreciate your help in doing so. If you find something here that is of value, please share it with others. If you are on Facebook, “like” the posts on your page so others can see them. If you are following me on Twitter, please “retweet” the notices of these meditations. If you have a blog of your own, please include mine in your links (a favor I will gladly reciprocate). Many thanks!

====================

Father Funston is the rector of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Medina, Ohio.

This may be the most puzzling and disconcerting story in the Gospels. I was taught that Jews had a tradition of denigrating Gentiles as “dogs” — a reference to many negative characteristics of dogs as scavengers, publically shameless, and so on, and to their ritual uncleanness in Jewish law — and that Jesus is just being a typical First Century Palestinian Jew in referring to this obnoxious foreign woman in this way. But . . . the last time I had to preach on this text I did some additional research and found a well-documented paper by a Roman Catholic scholar who had found absolutely no historical literature to substantiate that exegetical tradition. None! In fact, it appears that the first instance in the literary record of a Jew insulting a Gentile by calling him or her a “dog” is . . . this one. Jesus. Insulting this woman.

This may be the most puzzling and disconcerting story in the Gospels. I was taught that Jews had a tradition of denigrating Gentiles as “dogs” — a reference to many negative characteristics of dogs as scavengers, publically shameless, and so on, and to their ritual uncleanness in Jewish law — and that Jesus is just being a typical First Century Palestinian Jew in referring to this obnoxious foreign woman in this way. But . . . the last time I had to preach on this text I did some additional research and found a well-documented paper by a Roman Catholic scholar who had found absolutely no historical literature to substantiate that exegetical tradition. None! In fact, it appears that the first instance in the literary record of a Jew insulting a Gentile by calling him or her a “dog” is . . . this one. Jesus. Insulting this woman. Two weeks ago our Gospel lesson was the story of Nicodemus with whom Jesus discussed birth. Jesus talked about being born anew, being born of spirit, but Nicodemus could only think of physical birth and talked about crawling back into his mother’s womb. The words were all about birth, but the lesson wasn’t really about birth, at all. It was, as we all know, about a new life in Christ, about becoming a new person through the power of God.

Two weeks ago our Gospel lesson was the story of Nicodemus with whom Jesus discussed birth. Jesus talked about being born anew, being born of spirit, but Nicodemus could only think of physical birth and talked about crawling back into his mother’s womb. The words were all about birth, but the lesson wasn’t really about birth, at all. It was, as we all know, about a new life in Christ, about becoming a new person through the power of God. A couple of months ago, a friend mine published a list of the

A couple of months ago, a friend mine published a list of the  The past couple of weeks my wife and I have suffered the slings and arrows of some sort of intestinal virus, or so we think. She had it first, seemed to get better, suffered a relapse. I didn’t seem to “catch” it from her, but a few days after her last bout I suffered an attack of what I thought was “food poisoning.” Three days later I’m not so sure.

The past couple of weeks my wife and I have suffered the slings and arrows of some sort of intestinal virus, or so we think. She had it first, seemed to get better, suffered a relapse. I didn’t seem to “catch” it from her, but a few days after her last bout I suffered an attack of what I thought was “food poisoning.” Three days later I’m not so sure. Jesus sure spends a lot of time on mountains! And I can understand why. They are generally inaccessible to all but the most determined making them the perfect place for someone who needs a little “down” time, a little bit of “I’m exhausted by all of this and need to recharge” time, a little “leave me be for a while” time.

Jesus sure spends a lot of time on mountains! And I can understand why. They are generally inaccessible to all but the most determined making them the perfect place for someone who needs a little “down” time, a little bit of “I’m exhausted by all of this and need to recharge” time, a little “leave me be for a while” time.  I have a hard time with the beheading thing . . . . I don’t know what it is, but there’s something about cutting someone’s head off that just appalls me.

I have a hard time with the beheading thing . . . . I don’t know what it is, but there’s something about cutting someone’s head off that just appalls me.  It may be pedestrian of me, but I can’t stop thinking of the messenger’s feet and whether this passage of Isaiah is really very well chosen as the Old Testament lesson for Morning Prayer on the Feast of the Annunciation! Reading the rest of the lesson with its message of redemption and salvation, one can see why it is set out in the special set of Daily Office readings for this feast day, but I can’t get my mind off the feet.

It may be pedestrian of me, but I can’t stop thinking of the messenger’s feet and whether this passage of Isaiah is really very well chosen as the Old Testament lesson for Morning Prayer on the Feast of the Annunciation! Reading the rest of the lesson with its message of redemption and salvation, one can see why it is set out in the special set of Daily Office readings for this feast day, but I can’t get my mind off the feet. This verse is from the optional additional evening psalm for today. I chose to focus on it because today is the commemoration (on the Episcopal Church’s sanctoral calendar) of the martyred Roman Catholic Archbishop of San Salvador, Oscar Romero. Today is the 34th anniversary of his assassination; he was shot to death while celebrating a private funeral mass for the mother of a friend.

This verse is from the optional additional evening psalm for today. I chose to focus on it because today is the commemoration (on the Episcopal Church’s sanctoral calendar) of the martyred Roman Catholic Archbishop of San Salvador, Oscar Romero. Today is the 34th anniversary of his assassination; he was shot to death while celebrating a private funeral mass for the mother of a friend. The story of the reaction of the people to the curing of the Gerasene demoniac is, I think, unique among the healing stories in the Gospels. Most of the time when people hear of or witness one of Jesus’ healings, he is then swamped by crowds and sometimes has to flee them. Here, we are told that he is begged to go away. As I read the passage, I thought of Isaiah’s reaction to his call: “Woe is me! I am lost, for I am a man of unclean lips, and I live among a people of unclean lips” (Isa. 6:5) These folks are those who realize they are “a people of unclean lips.” Like Isaiah, they fear being in the presence of holiness.

The story of the reaction of the people to the curing of the Gerasene demoniac is, I think, unique among the healing stories in the Gospels. Most of the time when people hear of or witness one of Jesus’ healings, he is then swamped by crowds and sometimes has to flee them. Here, we are told that he is begged to go away. As I read the passage, I thought of Isaiah’s reaction to his call: “Woe is me! I am lost, for I am a man of unclean lips, and I live among a people of unclean lips” (Isa. 6:5) These folks are those who realize they are “a people of unclean lips.” Like Isaiah, they fear being in the presence of holiness.