Revised Common Lectionary for the Third Sunday in Lent, Year B: Exodus 20:1-17; Psalm 19; 1 Corinthians 1:18-25; and John 2:13-22

The third of the questions asked by a parishioner that I would like to tackle is “What does ‘social justice’ mean in the Episcopal Church?” Social justice generally refers to the idea of creating a society or institution that is based on the principles of equality and solidarity, that understands and values human rights, and that “strive[s] for justice and peace among all people, and respect[s] the dignity of every human being.” (The Book of Common Prayer, 1979, page 305)

In the Episcopal Church, we believe that our Christian faith has both a personal (or individual) dimension and a corporate (or social) dimension; we believe our call to the Christian life has both a contemplative (or prayerful) dimension and a public (or active) dimension. We refer to this as a “cruciform” (or cross-shaped) understanding of the faith, for as St. Paul said, “We proclaim Christ crucified.” In the one dimension, the cross of Christ has a vertical member which symbolizes our personal, individual, contemplative, and prayerful relationship with our God and creator. But the cross also has a horizontal member illustrating the corporate, social, public, and active ministry to which we are all called. A lovely prayer mission in the Daily Office of Morning Prayer recalls this horizontal dimension as we pray to our Savior:

Lord Jesus Christ, you stretched out your arms of love on the hard wood of the cross that everyone might come within the reach of your saving embrace: So clothe us in your Spirit that we, reaching forth our hands in love, may bring those who do not know you to the knowledge and love of you; for the honor of your Name. Amen.

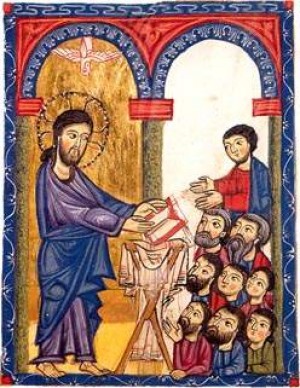

And today’s Gospel lesson, Jesus cleansing the Temple, exemplifies the active, social justice ministry to which he calls his church. Throughout his ministry on earth, the Son of God did not simply call individuals to be good persons: he insisted that the systems and institutions of society were to be reformed so that they would reflect the values inherent in the Law of Moses (from which come the Ten Commandments we read in today’s lesson from the Hebrew Scriptures) and the word of God spoken through the Prophets.

And today’s Gospel lesson, Jesus cleansing the Temple, exemplifies the active, social justice ministry to which he calls his church. Throughout his ministry on earth, the Son of God did not simply call individuals to be good persons: he insisted that the systems and institutions of society were to be reformed so that they would reflect the values inherent in the Law of Moses (from which come the Ten Commandments we read in today’s lesson from the Hebrew Scriptures) and the word of God spoken through the Prophets.

Jesus began his public ministry by reading these words from the Prophet Isaiah:

The Spirit of the Lord is upon me, because he has anointed me to bring good news to the poor. He has sent me to proclaim release to the captives and recovery of sight to the blind, to let the oppressed go free, to proclaim the year of the Lord’s favor. (Luke 4:18-19)

To bring good news to the poor, to release captives, to let the oppressed go free … these words herald and describe systemic and institutional changes in society, not simply a change for some individuals but for all of God’s children.

Jesus’ ministry and the Christian call to social justice are informed by the word of God spoken through Moses who ordered the Hebrews:

You shall not abuse any widow or orphan. If you do abuse them, when they cry out to me, I will surely heed their cry. (Exodus 22:22-23)

Jesus recognized and we recognize that widows and orphans have been and are still abused in many places around the world, and as the people of God we must heed their cries and reform the systems and institutions which permit, and often even inflict, that abuse. This is Christian social justice.

Jesus’ ministry and the Christian call to social justice are informed by the word of God spoken to the leaders of God’s people:

You shall take no bribe, for a bribe blinds the officials, and subverts the cause of those who are in the right. You shall not oppress a resident alien; you know the heart of an alien, for you were aliens in the land of Egypt. (Exodus 23:8-9)

Jesus knew and we know that the leaders of nations do take bribes (and “kickbacks” and “earmarks” and “political contributions”), that political influence is peddled in many ways, that resident aliens are oppressed in this and many countries, and that the causes of those in the right are often subverted. As the people of God, we must stand for changes in power structures to prevent these abuses. This is Christian social justice.

The Christian call to social justice is informed by Jesus’ own words promised to those who are faithful:

I was hungry and you gave me food, I was thirsty and you gave me something to drink, I was a stranger and you welcomed me, I was naked and you gave me clothing, I was sick and you took care of me, I was in prison and you visited me. (Matthew 25:35-36)

We see in these words a call not only to feed those who are now hungry, but to prevent others from going without food. We are called not only to give drink to those who are now parched, but to prevent others from becoming thirsty. We are called not only to cover those who are now unclothed, but to prevent others from becoming naked. We know all too well that despite Christ’s mother’s song, the powerful have not yet been brought down from their thrones; the lowly have not yet been lifted up; the hungry have not yet been filled with good things; and the rich have yet to be sent away empty. We, the people of God, are called to accomplish these things. This is Christian social justice.

Our catechism (beginning on page 845 of The Book of Common Prayer) informs us that the mission of the church “is to restore all people to unity with God and each other” and that the church “pursues its mission as it prays and worships, proclaims the Gospel, and promotes justice, peace, and love.” Furthermore, “The church carries out its mission through the ministry of all its members.” You will recall from the baptismal covenant that our ministry, individually and collectively, is to “seek and serve Christ in all persons, loving [our] neighbor as [our]self” and to “strive for justice and peace among all people, … respect[ing] the dignity of every human being.” (BCP, page 305) This is Christian social justice.

For nearly the past half-century, the Episcopal Church, together with our brothers and sisters throughout the Anglican Communion, has recommended that all our members and parishes measure themselves from time to time against certain core Christian priorities, which are called the Five Marks of Mission:

- To proclaim the good news of the Kingdom of God;

- To teach, baptize and nurture new believers;

- To respond to human need by loving service;

- To seek to transform the unjust structures of society; and

- To strive to safe-guard the integrity of creation and to sustain and renew the life of the earth.

In pursuit of the last two of those “marks” (which summarize social justice ministry), the Episcopal Church in 2006 committed itself to work with others in the Anglican Communion, with other churches and religious bodies in ecumenical and interfaith cooperation, with secular non-governmental organizations, and with our government and those of other nations to accomplish as quickly as possible eight “Millenium Development Goals” set out by the United Nations:

- Eradicate extreme poverty and hunger

- Achieve universal primary education

- Promote gender equality and empower women

- Reduce child mortality rates

- Improve maternal health

- Combat HIV/AIDS, malaria, and other diseases

- Ensure environmental sustainability

- Develop a global partnership for development

In pursuit of the gospel mandate, the Episcopal Church has dedicated itself to these goals. This is Christian social justice.

The Anglican Marks of Mission and the Episcopal Church’s commitment to the UN’s Millennium Development Goals are our church’s way of putting into positive action the last seven of the Ten Commandments. We understand these to form a sort of basic contract listing some fairly fundamental expectations of God with regard to social justice in the global human community. Ultimately, Jesus would summarize them in the two great commandments, “You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your mind, and with all your strength …. You shall love your neighbor as yourself.” (Mark 12:30-31) In today’s epistle lesson, St. Paul reminds us that this contract is beyond the wisdom of the world, and that it is our responsibility to fulfill these divine expectations without sacrificing the spirit of the Law which, as foolish as it may sound to the wise of this world, is to build up the whole human community. This is the goal of Christian social justice.

In Jesus’ time, the religious, political, and social institutions had forgotten this. In place of the fair and equitable financial system anticipated in the laws set out in Exodus and Leviticus, Jesus found the bankers sitting in the Temple courtyard taking advantage of the poor, exchanging Roman drachmas for temple sheckles at outrageous conversion rates and pocketing unacceptably high profits. He exercised an active social justice ministry and threw them out. Instead of priests and Levites aiding the people in their relationship to God, he found the sellers of sacrificial animals preying on their sorrows, cheapening their thanksgivings, and profiting from their earnest effort to be faithful. He exercised an active social justice ministry and drove them away.

Jesus cleansing the Temple exemplifies the active, social justice ministry to which God calls the church. Throughout his ministry on earth, the Son of God did not simply call individuals to be good persons: he insisted that the systems and institutions of society were to be reformed so that they would reflect the values inherent in the Law and the word of God. Because of human frailty, because of human greed, because of human failure, the systems and institutions of society are always in need of reform and, thus, the church is always called to an active ministry of social justice.

Let us pray:

Almighty God, who created us in your image: Grant us grace fearlessly to contend against evil and to make no peace with oppression; and, that we may reverently use our freedom, help us to employ it in the maintenance of justice in our communities and among the nations, to the glory of your holy Name; through Jesus Christ our Lord, who lives and reigns with you and the Holy Spirit, one God, now and for ever. Amen. (BCP, page 246)

I’ve always been troubled by St. Paul’s “adoption” language. I suppose I’m influenced by one of my favorite authors, the Victorian Scot George MacDonald who, in one of his Unspoken Sermons, absolutely bridled at this notion of “adoption”. MacDonald’s problem with “adoption” is that it suggests that God is not our father to begin with. MacDonald wrote, “Who is my father? Am I not his to begin with? Is God not my very own Father? Is he my Father only in a sort or fashion – by a legal contrivance? Truly, much love may lie in adoption, but if I accept it from any one, I allow myself the child of another! The adoption of God would indeed be a blessed thing if another than he had given me being! but if he gave me being, then it means no reception, but a repudiation.” How awful to find in words meant to build up one’s faith the exact opposite effect! Better to seek an alternative translation of the obscure Greek than to be turned away from God by a poor interpretation! ~ In the New Revised Standard Version of Scripture, the word adoption appears five times, all in Paul’s epistles. Nowhere else. The original Koine Greek in all five occurrences is huiothesia, a word Paul seems to have made up! I am given to understand that the word is a compound one which literally means, “to place as a son.” One Greek lexicon defines it as meaning “to formally and legally declare that someone who is not one’s own child is henceforth to be treated and cared for as one’s own child, including complete rights of inheritance.” Perhaps Paul’s meaning might have been better expressed if this made-up word were interpreted as “inheritance” for surely in this passage that is the point he is making and emphasizes in the next few verses saying we are “joint heirs with Christ.” This seems also to be his meaning in Galatians 4:5 and in Ephesians 1:5, and one could argue that it would make even better sense in the other two occurrences in this letter, Romans 8:23 and 9:4. ~ Not everyone, of course, finds the term so off-putting. Archbishop Desmond Tutu found it reassuring: “God loves us. There is nothing we can do to make God love us more and nothing we can do to make God love us less. Our adoption is forever. We are all God’s children.” Certainly, this is the sense we find in Peter’s First Letter. Peter does not use the “adoption” motif, however; he instead uses the same metaphor Jesus used in the conversation from which comes the Revised Common Lectionary Gospel reading for today, the Fourth Sunday in Lent (John 3:14-21). In John 3:3, Jesus tells Nicodemus a man must be born again to see the kingdom of God. In First Peter we find the born-again metaphor of John’s Gospel combined with the inheritance argument of Paul: “Blessed be the God and Father of our Lord Jesus Christ, who according to his great mercy has caused us to be born again to a living hope through the resurrection of Jesus Christ from the dead, to obtain an inheritance which is imperishable and undefiled and will not fade away, reserved in heaven for you, who are protected by the power of God through faith for a salvation ready to be revealed in the last time.” ~ So whether it is by adoption, or by inheritance, or by being born again, or by whatever other metaphor one finds meaningful, our relationship to God, the relationship of a child to a father, is eternal and (as we are reminded in the Epistle from today’s RCL selections for the Eucharist) “it is the gift of God.”

I’ve always been troubled by St. Paul’s “adoption” language. I suppose I’m influenced by one of my favorite authors, the Victorian Scot George MacDonald who, in one of his Unspoken Sermons, absolutely bridled at this notion of “adoption”. MacDonald’s problem with “adoption” is that it suggests that God is not our father to begin with. MacDonald wrote, “Who is my father? Am I not his to begin with? Is God not my very own Father? Is he my Father only in a sort or fashion – by a legal contrivance? Truly, much love may lie in adoption, but if I accept it from any one, I allow myself the child of another! The adoption of God would indeed be a blessed thing if another than he had given me being! but if he gave me being, then it means no reception, but a repudiation.” How awful to find in words meant to build up one’s faith the exact opposite effect! Better to seek an alternative translation of the obscure Greek than to be turned away from God by a poor interpretation! ~ In the New Revised Standard Version of Scripture, the word adoption appears five times, all in Paul’s epistles. Nowhere else. The original Koine Greek in all five occurrences is huiothesia, a word Paul seems to have made up! I am given to understand that the word is a compound one which literally means, “to place as a son.” One Greek lexicon defines it as meaning “to formally and legally declare that someone who is not one’s own child is henceforth to be treated and cared for as one’s own child, including complete rights of inheritance.” Perhaps Paul’s meaning might have been better expressed if this made-up word were interpreted as “inheritance” for surely in this passage that is the point he is making and emphasizes in the next few verses saying we are “joint heirs with Christ.” This seems also to be his meaning in Galatians 4:5 and in Ephesians 1:5, and one could argue that it would make even better sense in the other two occurrences in this letter, Romans 8:23 and 9:4. ~ Not everyone, of course, finds the term so off-putting. Archbishop Desmond Tutu found it reassuring: “God loves us. There is nothing we can do to make God love us more and nothing we can do to make God love us less. Our adoption is forever. We are all God’s children.” Certainly, this is the sense we find in Peter’s First Letter. Peter does not use the “adoption” motif, however; he instead uses the same metaphor Jesus used in the conversation from which comes the Revised Common Lectionary Gospel reading for today, the Fourth Sunday in Lent (John 3:14-21). In John 3:3, Jesus tells Nicodemus a man must be born again to see the kingdom of God. In First Peter we find the born-again metaphor of John’s Gospel combined with the inheritance argument of Paul: “Blessed be the God and Father of our Lord Jesus Christ, who according to his great mercy has caused us to be born again to a living hope through the resurrection of Jesus Christ from the dead, to obtain an inheritance which is imperishable and undefiled and will not fade away, reserved in heaven for you, who are protected by the power of God through faith for a salvation ready to be revealed in the last time.” ~ So whether it is by adoption, or by inheritance, or by being born again, or by whatever other metaphor one finds meaningful, our relationship to God, the relationship of a child to a father, is eternal and (as we are reminded in the Epistle from today’s RCL selections for the Eucharist) “it is the gift of God.” This conversation comes after a confrontation with the Pharisees and scribes who criticized Jesus and the disciples for not washing their hands before eating (and some commentary from Mark about washing food from the market and “cups, pots, and bronze kettles”). Jesus said to his critics, “You have a fine way of rejecting the commandment of God in order to keep your tradition!” (Mark 7:9) ~ Jesus is here addressing the rabbinical (as opposed to biblical) laws called the mitzvot d’rabbanan (“commandmens of the rabbis”). These are additions to the laws that come directly from Torah. These rabbinic laws are still referred to as mitzvot (“commandments”), even though they are not part of the original 613 mitzvot found in Scripture. They are considered to be as binding as Torah laws. The mitzvot d’rabbanan are commonly divided into three categories: gezeirah, takkanah, and minhag. ~ The names of these divisions give us a clue to their origins. Gezeirah derives from the Hebrew root word for “separate”; these rules are considered a “fence around the Torah”; they prevent obedient Jews from even getting close to violating the Law. Takkanah derives from a root word mean “fix” or “remedy”; these are revisions of Torah ordinances that no longer satisfy the requirements of the times or circumstances (arguably, these revisions can be deduced from and do not violate the Torah). Minhag means “customs”; these have developed for worthy religious reasons, not from reasoned decision-making, and have continued long enough to become binding religious practices. ~ We Episcopalians have plenty of all three types in our own denominational practice. We have general and diocesan canons; we have policies and by-laws; we have “the ways we’ve always done it.” ~ When we try to build “fences” around sacred things, I have a suspicion about what we are doing. Anglican history tells us that Archbishop William Laud started the Episcopal “altar rail” tradition by ordering that fences be placed around altars because he was afraid Puritans would allow their dogs to urinate on them! I think that’s iconic of what the mitzvot d’rabbanam and our own canons, by-laws, and “we’ve always done it that ways” are about – Fear! We are trying to protect that which we originally valued from that which we fear, even though we may not be able to name the source of our fear. And it is to that unnamed fear that Jesus speaks in his follow-up conversation with the disciples. Fear, irrational, unreasoning, often unnamed fear, is powerful and when it takes hold of the human heart a lot of evil can result, “for it is from within, from the human heart, that evil intentions come.” It was, I believe, out of fear that the Pharisees had concentrated so much on the externals of religious practice. So intent were they on the fences, remedies, and customs that had grown up around the Jewish faith that the internals of faith, that which was originally valued, had been forgotten or even avoided. ~ The collect for this Saturday in the third week of Lent includes a petition that God keep watch over the church because it is “grounded in human weakness and cannot maintain itself without [God’s] aid.” No human weakness, I think, is greater or more powerful than irrational, unreasoning, and often unnamed fear. And there is no greater remedy for fear than the the love of God and God’s offer of freedom in Christ.

This conversation comes after a confrontation with the Pharisees and scribes who criticized Jesus and the disciples for not washing their hands before eating (and some commentary from Mark about washing food from the market and “cups, pots, and bronze kettles”). Jesus said to his critics, “You have a fine way of rejecting the commandment of God in order to keep your tradition!” (Mark 7:9) ~ Jesus is here addressing the rabbinical (as opposed to biblical) laws called the mitzvot d’rabbanan (“commandmens of the rabbis”). These are additions to the laws that come directly from Torah. These rabbinic laws are still referred to as mitzvot (“commandments”), even though they are not part of the original 613 mitzvot found in Scripture. They are considered to be as binding as Torah laws. The mitzvot d’rabbanan are commonly divided into three categories: gezeirah, takkanah, and minhag. ~ The names of these divisions give us a clue to their origins. Gezeirah derives from the Hebrew root word for “separate”; these rules are considered a “fence around the Torah”; they prevent obedient Jews from even getting close to violating the Law. Takkanah derives from a root word mean “fix” or “remedy”; these are revisions of Torah ordinances that no longer satisfy the requirements of the times or circumstances (arguably, these revisions can be deduced from and do not violate the Torah). Minhag means “customs”; these have developed for worthy religious reasons, not from reasoned decision-making, and have continued long enough to become binding religious practices. ~ We Episcopalians have plenty of all three types in our own denominational practice. We have general and diocesan canons; we have policies and by-laws; we have “the ways we’ve always done it.” ~ When we try to build “fences” around sacred things, I have a suspicion about what we are doing. Anglican history tells us that Archbishop William Laud started the Episcopal “altar rail” tradition by ordering that fences be placed around altars because he was afraid Puritans would allow their dogs to urinate on them! I think that’s iconic of what the mitzvot d’rabbanam and our own canons, by-laws, and “we’ve always done it that ways” are about – Fear! We are trying to protect that which we originally valued from that which we fear, even though we may not be able to name the source of our fear. And it is to that unnamed fear that Jesus speaks in his follow-up conversation with the disciples. Fear, irrational, unreasoning, often unnamed fear, is powerful and when it takes hold of the human heart a lot of evil can result, “for it is from within, from the human heart, that evil intentions come.” It was, I believe, out of fear that the Pharisees had concentrated so much on the externals of religious practice. So intent were they on the fences, remedies, and customs that had grown up around the Jewish faith that the internals of faith, that which was originally valued, had been forgotten or even avoided. ~ The collect for this Saturday in the third week of Lent includes a petition that God keep watch over the church because it is “grounded in human weakness and cannot maintain itself without [God’s] aid.” No human weakness, I think, is greater or more powerful than irrational, unreasoning, and often unnamed fear. And there is no greater remedy for fear than the the love of God and God’s offer of freedom in Christ. Confession time … this is one of those passages from the Pauline Epistles that makes me hate Paul. He’s such a self-important braggart! “Look at me,” he seems to be saying, “Look at all I’ve done, all the sacrifices I’ve made, all the effort I’ve put into sharing the Gospel with you! I am really the best evangelist there ever was!” ~ OK … I don’t hate Paul. I know he’s not really being an arrogant braggart in this letter … but doesn’t some of his writing sure seem that way? ~ What is going on here is that Paul is talking about flexibility! The Lord, speaking through the prophet Jeremiah, reminds us that we are clay in God’s hands: “Just like the clay in the potter’s hand, so are you in my hand, O house of Israel.” (Jer. 18:6b) It seems that many people think that once the clay is formed for a specific purpose and will never again be reshaped for anything else, but that’s not the way things work in life and especially not in ministry. Spiritual clay cannot be rigid; it must be flexible to be formed for one purpose and then reformed for a different type of work according to God’s will. When Jeremiah went to the potter’s house as God led him, he saw that the vessel the potter was making ended up being reworked into another vessel as seemed good to the potter. God then asked, “Can I not do the same with you?” (18:5-6a) It seems to me that Paul (in is own inimitable fashion) is simply saying that God worked and reworked him time and time again, and that he had learned to be flexible. ~ An old friend used to be the Altar Guild director in her church. On the wall of the sacristy she put up a poster of wheat blowing in the wind; the caption read, “Blessed are the flexible, for they will never be bent out of shape.”

Confession time … this is one of those passages from the Pauline Epistles that makes me hate Paul. He’s such a self-important braggart! “Look at me,” he seems to be saying, “Look at all I’ve done, all the sacrifices I’ve made, all the effort I’ve put into sharing the Gospel with you! I am really the best evangelist there ever was!” ~ OK … I don’t hate Paul. I know he’s not really being an arrogant braggart in this letter … but doesn’t some of his writing sure seem that way? ~ What is going on here is that Paul is talking about flexibility! The Lord, speaking through the prophet Jeremiah, reminds us that we are clay in God’s hands: “Just like the clay in the potter’s hand, so are you in my hand, O house of Israel.” (Jer. 18:6b) It seems that many people think that once the clay is formed for a specific purpose and will never again be reshaped for anything else, but that’s not the way things work in life and especially not in ministry. Spiritual clay cannot be rigid; it must be flexible to be formed for one purpose and then reformed for a different type of work according to God’s will. When Jeremiah went to the potter’s house as God led him, he saw that the vessel the potter was making ended up being reworked into another vessel as seemed good to the potter. God then asked, “Can I not do the same with you?” (18:5-6a) It seems to me that Paul (in is own inimitable fashion) is simply saying that God worked and reworked him time and time again, and that he had learned to be flexible. ~ An old friend used to be the Altar Guild director in her church. On the wall of the sacristy she put up a poster of wheat blowing in the wind; the caption read, “Blessed are the flexible, for they will never be bent out of shape.” In between these two sections from Mark’s Gospel Jesus teaches a great crowd of people and then feeds them with five loaves of bread and two fish; the crowd “numbered five thousand men” and who knows how many women and children. But what draws my attention today are the words of Jesus, “Come away to a deserted place all by yourselves and rest a while” and Mark’s words at the end, “He made his disciples get into the boat and go [away]” and “he went up on the mountain to pray.” Lots and lots of ministry activity bracketed by “down time”, time away from the demands of the crowd, time to rest, time to pray, times of sabbath. Mark doesn’t actually call these “sabbath times”, but that’s what they were. Part of the genius of the Jewish faith (and, by extension from it and by the modeling of its Founder, of the Christian faith) is that the human need for rest is made sacred. “God blessed the seventh day and sanctified it, because in it He rested from all His work which God had created and made.” (Gen. 2:3) “Remember the sabbath day, to keep it holy. Six days you shall labor and do all your work, but the seventh day is a sabbath of the Lord your God ; in it you shall not do any work.” (Exod. 20:8-10) Jesus famously remarked, “The Sabbath was made for man, and not man for the Sabbath.” (Mark 2:27) Methodist writer Leonard Sweet interprets Jesus as meaning that it’s not so much that we keep the Sabbath, but that the Sabbath keeps us. It keeps us whole, keeps us sane, and keeps us spiritually alive. In today’s story from Mark’s Gospel we tend to focus on the feeding of the five thousand (the part I left out up above), but I’m beginning to believe that the really important part of the story are the “brackets”, the times of rest. Do not neglect to “come [or go] away to a desert place by yourselves and rest a while” on a regular basis!

In between these two sections from Mark’s Gospel Jesus teaches a great crowd of people and then feeds them with five loaves of bread and two fish; the crowd “numbered five thousand men” and who knows how many women and children. But what draws my attention today are the words of Jesus, “Come away to a deserted place all by yourselves and rest a while” and Mark’s words at the end, “He made his disciples get into the boat and go [away]” and “he went up on the mountain to pray.” Lots and lots of ministry activity bracketed by “down time”, time away from the demands of the crowd, time to rest, time to pray, times of sabbath. Mark doesn’t actually call these “sabbath times”, but that’s what they were. Part of the genius of the Jewish faith (and, by extension from it and by the modeling of its Founder, of the Christian faith) is that the human need for rest is made sacred. “God blessed the seventh day and sanctified it, because in it He rested from all His work which God had created and made.” (Gen. 2:3) “Remember the sabbath day, to keep it holy. Six days you shall labor and do all your work, but the seventh day is a sabbath of the Lord your God ; in it you shall not do any work.” (Exod. 20:8-10) Jesus famously remarked, “The Sabbath was made for man, and not man for the Sabbath.” (Mark 2:27) Methodist writer Leonard Sweet interprets Jesus as meaning that it’s not so much that we keep the Sabbath, but that the Sabbath keeps us. It keeps us whole, keeps us sane, and keeps us spiritually alive. In today’s story from Mark’s Gospel we tend to focus on the feeding of the five thousand (the part I left out up above), but I’m beginning to believe that the really important part of the story are the “brackets”, the times of rest. Do not neglect to “come [or go] away to a desert place by yourselves and rest a while” on a regular basis! Every time I read this story, competing visions of the scene do battle in my imagination. First, there is the image of Rita Hayworth dancing the lascivious “dance of the seven veils” before Herod (played by Charles Laughton) in the movie Salomé (the name given Herod’s step-daughter by Flavius Josephus in his histories; her name is not mentioned in the Bible). If I recall correctly, there is a similarly sensual portrayal in the movie The Greatest Story Ever Told. The other image I see with my mind’s eye is of a much younger dancer, a pre-adolescent child. In the original Koine Greek, she is referred to as a korasion (vv. 22 and 28), the same word used in Monday’s gospel story of the healing of Jairus’s daughter. In that story the word is translated as “little girl” an applied to a child twelve years of age, a girl not yet old enough to be married. ~ As popular as the Rita Hayworth version is, I’d rather go with the little girl version. I’d rather not see the dance as part and parcel with the evil done to John the Baptist, which the lewdness of the strip-tease version suggests. I prefer to see this as a tale of innocence perverted, a child’s sweet gift of a simple dance taken advantage of by a scheming, vengeful adult, a cautionary tale (if you will) of purity sullied. Dance, in itself, should be thought of as a good thing. ~ When our son announced his engagement and then the couple announced their wedding date, and let us know that there would be a formal reception afterward with dancing, my wife and I decided to take ballroom dance classes. We discovered that dancing is not for sissies! It turned out to be darned difficult for rhythmically challenged folks like us; it also turned out to be fairly demanding physical exercise. But I enjoyed it and I’m glad we took the classes. I’m hoping we’ll take some more and make dancing a regular part of our lives. One should remember and heed the advice of St. Augustine (354-430):

Every time I read this story, competing visions of the scene do battle in my imagination. First, there is the image of Rita Hayworth dancing the lascivious “dance of the seven veils” before Herod (played by Charles Laughton) in the movie Salomé (the name given Herod’s step-daughter by Flavius Josephus in his histories; her name is not mentioned in the Bible). If I recall correctly, there is a similarly sensual portrayal in the movie The Greatest Story Ever Told. The other image I see with my mind’s eye is of a much younger dancer, a pre-adolescent child. In the original Koine Greek, she is referred to as a korasion (vv. 22 and 28), the same word used in Monday’s gospel story of the healing of Jairus’s daughter. In that story the word is translated as “little girl” an applied to a child twelve years of age, a girl not yet old enough to be married. ~ As popular as the Rita Hayworth version is, I’d rather go with the little girl version. I’d rather not see the dance as part and parcel with the evil done to John the Baptist, which the lewdness of the strip-tease version suggests. I prefer to see this as a tale of innocence perverted, a child’s sweet gift of a simple dance taken advantage of by a scheming, vengeful adult, a cautionary tale (if you will) of purity sullied. Dance, in itself, should be thought of as a good thing. ~ When our son announced his engagement and then the couple announced their wedding date, and let us know that there would be a formal reception afterward with dancing, my wife and I decided to take ballroom dance classes. We discovered that dancing is not for sissies! It turned out to be darned difficult for rhythmically challenged folks like us; it also turned out to be fairly demanding physical exercise. But I enjoyed it and I’m glad we took the classes. I’m hoping we’ll take some more and make dancing a regular part of our lives. One should remember and heed the advice of St. Augustine (354-430): There is so much in this little story! It serves as a great illustration of two old sayings: “Familiarity breeds contempt” and “You can never go home again”. Jesus’ home-town friends were too familiar with him. They’d known him since he was a boy. He’d done the equivalent of delivering their papers, mowing their lawns, playing with their kids, climbing their trees. Those who were his own generation knew him as fellow student, someone they’d sat in synagogue with, a working stiff making chairs and tables in his father’s workshop. They couldn’t accept him as anything more or different, and certainly not as religious leader! Their familiarity with him bred their contempt of his ministry, and that contempt came out in the form of old rumors and gossip: “This is Mary’s son” not “This is Joseph’s son” … those old stories about his parentage. They took offense at him and they became offensive and contemptuous in return. After this incident, Jesus left Nazareth and never returned. Despite Jesus’ ministry, his gifts for teaching and preaching, his ability to heal, in Nazareth he could never be more than his family’s and his friends’ memories allowed: he was a carpenter, how could he ever be anything else? Sometimes you can’t go home again because people are blinded by their memories and only see what was “back in the day”. Jesus realized it was time to detach with love and walk away. ~ In the Episcopal Church, we have a special prayer or “collect” that is to be said at each celebration of the Eucharist; there is such a prayer for each weekday in Lent. The collect for today includes the petition, “Grant that we, to whom you have given a fervent desire to pray, may, by your mighty aid, be defended and comforted in all dangers and adversities.” Sometimes the adversities we face come from those whom we expect to be our greatest supporters, friends and family who can’t let go of prejudices, presuppositions, and presumptions. Sometimes the greatest source of comfort in those situations is distance. If we have to detach and walk away, this little story from Mark’s Gospel reminds us that Jesus has been there before and shares the pain of family separation with us.

There is so much in this little story! It serves as a great illustration of two old sayings: “Familiarity breeds contempt” and “You can never go home again”. Jesus’ home-town friends were too familiar with him. They’d known him since he was a boy. He’d done the equivalent of delivering their papers, mowing their lawns, playing with their kids, climbing their trees. Those who were his own generation knew him as fellow student, someone they’d sat in synagogue with, a working stiff making chairs and tables in his father’s workshop. They couldn’t accept him as anything more or different, and certainly not as religious leader! Their familiarity with him bred their contempt of his ministry, and that contempt came out in the form of old rumors and gossip: “This is Mary’s son” not “This is Joseph’s son” … those old stories about his parentage. They took offense at him and they became offensive and contemptuous in return. After this incident, Jesus left Nazareth and never returned. Despite Jesus’ ministry, his gifts for teaching and preaching, his ability to heal, in Nazareth he could never be more than his family’s and his friends’ memories allowed: he was a carpenter, how could he ever be anything else? Sometimes you can’t go home again because people are blinded by their memories and only see what was “back in the day”. Jesus realized it was time to detach with love and walk away. ~ In the Episcopal Church, we have a special prayer or “collect” that is to be said at each celebration of the Eucharist; there is such a prayer for each weekday in Lent. The collect for today includes the petition, “Grant that we, to whom you have given a fervent desire to pray, may, by your mighty aid, be defended and comforted in all dangers and adversities.” Sometimes the adversities we face come from those whom we expect to be our greatest supporters, friends and family who can’t let go of prejudices, presuppositions, and presumptions. Sometimes the greatest source of comfort in those situations is distance. If we have to detach and walk away, this little story from Mark’s Gospel reminds us that Jesus has been there before and shares the pain of family separation with us. What is most interesting and empowering about this story of the healing of Jairus’s daughter told in today’s reading from Mark’s Gospel is its ending. Jesus goes to the girl, takes her by the hand and says, “Talitha cum,” which Mark tells us means “Little girl, get up.” But Mark also later tells us that the girl was twelve years old. She is an adolescent and this is significant: by Jewish tradition, a girl becomes a woman at twelve years and one day. So this young girl was poised at the very threshold of womanhood, of taking her place in the community as an adult. So not a little girl, but nearly a young woman, got up at Jesus’ command. Jesus then said to those around them, “Give her something to eat.” He doesn’t say to her, young adult though she may be, “Go and make your own breakfast.” Instead, he turns to her family and says, “Give her something to eat.” After the healing and lifting up of the one cured, Jesus commends her to the care and nurture of the community. ~ In our society, even the best of medical care comes to an end and, as with Jairus’s daughter, the patient’s family must take over. In The Book of Common Prayer, a prayer “for the aged” asks that God “give them understanding helpers” (BCP 1979, page 830); this story reminds us that not only the elderly, but also the very young and those in the prime of life may, from time to time, have need of assistance, may be patients in the midst of illness or recovering from expert medical care. As caregivers, we who are members of their family (or other nuclear community) are the experts in their history; we know a lot about our loved one and about their own abilities to provide care and a safe setting. Among the common care responsibilities we may all someday be handling for a family member as he or she recovers from illness, injury, or surgery are personal care (bathing, eating, dressing, toileting), household care (cooking, cleaning, laundry, shopping), healthcare (medication management, physician’s appointments, physical therapy, wound treatment, injections), and emotional care (companionship, meaningful activities, conversation). ~ The end of Mark’s story of the Jairus’s daughter’s healing reminds us that these are Christ-like ministries empowered by God, not simply onerous family burdens. In The Book of Common Prayer there is also a lovely prayer entitled “For strength and confidence” following the liturgy of Ministration to the Sick: “Heavenly Father, giver of life and health: Comfort and relieve your sick servant N., and give your power of healing to those who minister to his/her needs, that he/she may be strengthened in his/her weakness and have confidence in your loving care; through Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen.” (BCP 1979, page 459) This story from Mark’s Gospel reminds us that family members are included among those to whom we ask God to give the “power of healing.”

What is most interesting and empowering about this story of the healing of Jairus’s daughter told in today’s reading from Mark’s Gospel is its ending. Jesus goes to the girl, takes her by the hand and says, “Talitha cum,” which Mark tells us means “Little girl, get up.” But Mark also later tells us that the girl was twelve years old. She is an adolescent and this is significant: by Jewish tradition, a girl becomes a woman at twelve years and one day. So this young girl was poised at the very threshold of womanhood, of taking her place in the community as an adult. So not a little girl, but nearly a young woman, got up at Jesus’ command. Jesus then said to those around them, “Give her something to eat.” He doesn’t say to her, young adult though she may be, “Go and make your own breakfast.” Instead, he turns to her family and says, “Give her something to eat.” After the healing and lifting up of the one cured, Jesus commends her to the care and nurture of the community. ~ In our society, even the best of medical care comes to an end and, as with Jairus’s daughter, the patient’s family must take over. In The Book of Common Prayer, a prayer “for the aged” asks that God “give them understanding helpers” (BCP 1979, page 830); this story reminds us that not only the elderly, but also the very young and those in the prime of life may, from time to time, have need of assistance, may be patients in the midst of illness or recovering from expert medical care. As caregivers, we who are members of their family (or other nuclear community) are the experts in their history; we know a lot about our loved one and about their own abilities to provide care and a safe setting. Among the common care responsibilities we may all someday be handling for a family member as he or she recovers from illness, injury, or surgery are personal care (bathing, eating, dressing, toileting), household care (cooking, cleaning, laundry, shopping), healthcare (medication management, physician’s appointments, physical therapy, wound treatment, injections), and emotional care (companionship, meaningful activities, conversation). ~ The end of Mark’s story of the Jairus’s daughter’s healing reminds us that these are Christ-like ministries empowered by God, not simply onerous family burdens. In The Book of Common Prayer there is also a lovely prayer entitled “For strength and confidence” following the liturgy of Ministration to the Sick: “Heavenly Father, giver of life and health: Comfort and relieve your sick servant N., and give your power of healing to those who minister to his/her needs, that he/she may be strengthened in his/her weakness and have confidence in your loving care; through Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen.” (BCP 1979, page 459) This story from Mark’s Gospel reminds us that family members are included among those to whom we ask God to give the “power of healing.” And today’s Gospel lesson, Jesus cleansing the Temple, exemplifies the active, social justice ministry to which he calls his church. Throughout his ministry on earth, the Son of God did not simply call individuals to be good persons: he insisted that the systems and institutions of society were to be reformed so that they would reflect the values inherent in the Law of Moses (from which come the Ten Commandments we read in today’s lesson from the Hebrew Scriptures) and the word of God spoken through the Prophets.

And today’s Gospel lesson, Jesus cleansing the Temple, exemplifies the active, social justice ministry to which he calls his church. Throughout his ministry on earth, the Son of God did not simply call individuals to be good persons: he insisted that the systems and institutions of society were to be reformed so that they would reflect the values inherent in the Law of Moses (from which come the Ten Commandments we read in today’s lesson from the Hebrew Scriptures) and the word of God spoken through the Prophets.  To our ancient ancestors, living water was the very essence of chaos. The oceans and seas, their waves, swift flowing rivers, waterfalls, cataracts, even peaceful ponds and lakes were considered chaotic and dangerous; they were very difficult even for the gods to control. The gods did battle with them; when the gods had won, creation followed. For example, in Egyptian mythology in the beginning there was only the swirling watery chaos, called Nu; out of the chaotic waters rose the sungod, Atum (later identified as Ra or Kephri), who subdued the waters and created the first dry land. We find echoes of this in Genesis 1 where “the earth was a formless void and darkness covered the face of the deep, while a wind from God swept over the face of the waters.” (v. 2) God subdues the waters by first separating them and then gathering those under the firmament into seas. The Lord makes reference to this creation myth when he answers Job: “Who shut in the sea with doors when it burst out from the womb? – when I made the clouds its garment, and thick darkness its swaddling band, and prescribed bounds for it, and set bars and doors, and said, ‘Thus far shall you come, and no farther, and here shall your proud waves be stopped’?” (Job 38:8-11) Perhaps the disciples had this in mind when, boating on the Galilean lake with Jesus during a storm, they asked “Who then is this, that even the wind and the sea obey him?” (Mark 4:41) Here in Psalm 93, God wins definitively, establishing world order, which “shall never be moved” (v. 1); God’s order cannot be changed or defeated. God rules over all of creation, even the forces of chaos. Each of us is subject to the chaos of feelings and emotions, our subjective reactions to a particular event. These reactions are characterized by an absence of reasoning; they are rambunctious, even primal. It is not uncommon to hear someone say, “I can’t trust my feelings” or “My emotions got away from me.” Sometimes these intense feelings are accompanied by physical and mental activity. Emotions are impulses to act, the instant plans for handling life that evolution has instilled in us, and in any of us these primal, instinctive reactions can become chaotic and uncontrolled. Psalm 93 assures us that God is mightier than even these most powerful and unpredictably chaotic forces. God is the perfect outlet for our emotions. When you, or your family, or your friends can’t handle your emotions, God can. As The Book of Common Prayer‘s Collect for the Third Sunday in Lent assures us, God can “keep us both outwardly in our bodies and inwardly in our souls, that we may be defended from all adversities which may happen to the body, and from all evil thoughts which may assault and hurt the soul,” especially our chaotic emotions.

To our ancient ancestors, living water was the very essence of chaos. The oceans and seas, their waves, swift flowing rivers, waterfalls, cataracts, even peaceful ponds and lakes were considered chaotic and dangerous; they were very difficult even for the gods to control. The gods did battle with them; when the gods had won, creation followed. For example, in Egyptian mythology in the beginning there was only the swirling watery chaos, called Nu; out of the chaotic waters rose the sungod, Atum (later identified as Ra or Kephri), who subdued the waters and created the first dry land. We find echoes of this in Genesis 1 where “the earth was a formless void and darkness covered the face of the deep, while a wind from God swept over the face of the waters.” (v. 2) God subdues the waters by first separating them and then gathering those under the firmament into seas. The Lord makes reference to this creation myth when he answers Job: “Who shut in the sea with doors when it burst out from the womb? – when I made the clouds its garment, and thick darkness its swaddling band, and prescribed bounds for it, and set bars and doors, and said, ‘Thus far shall you come, and no farther, and here shall your proud waves be stopped’?” (Job 38:8-11) Perhaps the disciples had this in mind when, boating on the Galilean lake with Jesus during a storm, they asked “Who then is this, that even the wind and the sea obey him?” (Mark 4:41) Here in Psalm 93, God wins definitively, establishing world order, which “shall never be moved” (v. 1); God’s order cannot be changed or defeated. God rules over all of creation, even the forces of chaos. Each of us is subject to the chaos of feelings and emotions, our subjective reactions to a particular event. These reactions are characterized by an absence of reasoning; they are rambunctious, even primal. It is not uncommon to hear someone say, “I can’t trust my feelings” or “My emotions got away from me.” Sometimes these intense feelings are accompanied by physical and mental activity. Emotions are impulses to act, the instant plans for handling life that evolution has instilled in us, and in any of us these primal, instinctive reactions can become chaotic and uncontrolled. Psalm 93 assures us that God is mightier than even these most powerful and unpredictably chaotic forces. God is the perfect outlet for our emotions. When you, or your family, or your friends can’t handle your emotions, God can. As The Book of Common Prayer‘s Collect for the Third Sunday in Lent assures us, God can “keep us both outwardly in our bodies and inwardly in our souls, that we may be defended from all adversities which may happen to the body, and from all evil thoughts which may assault and hurt the soul,” especially our chaotic emotions. This is a troubling text. Paul seems to be telling slaves to remain in their slavery, not to be concerned about their condition of servitude; this would say to others that they should not struggle for the liberation of slaves. Of course, Paul believed the end of this world was right around the corner and such earthly conditions as slavery or mastership would be abolished in his lifetime. He was wrong … so how does his text speak to us today? ~ Paul’s counsel to remain “in whatever condition you were called” should not be used as a justification for not seeking better circumstances for oneself and an improvement of one’s circumstances. Indeed, it is debatable that Paul even gave that advice to stay in one’s “condition” or “situation”. It is rather more probable, it seems to me, that his counsel is to remain steadfast in one’s conversion (Greek kalesis = calling) to Christian faith and brotherhood resisting the pressures of one’s prior status – slave or master, Jew or Greek, married or single, whatever that condition or status may be – and this might even mean a change in that circumstance. I am so persuaded by the arguments of S. Scott Bartchy, Professor of Christian Origins and the History of Religion, Department of History, UCLA. He has examined how the Greek word kalesis meaning “calling”, “invitation” or “summons” – correctly translated as vocatione by St. Jerome in the Vulgate and as “calling” (or “called”) in the Authorized Version – came to be translated in later English versions as “condition”. His surprising (and probably correct) conclusion is to blame Martin Luther and the influence of his German translation! Bartchy has argued that it is certain that Paul did not teach enslaved Christ-followers to “stay in slavery.” Rather, he exhorted them (and us) to “remain in the calling in Christ by which you were called.” Quite the opposite of a passive quietism accepting of unjust social institutions, Paul’s exhortation is to an active faith repenting our own “blindness to human need and suffering and our indifference to injustice and cruelty.” (From the American BCP’s Ash Wednesday Litany of Penitence, p. 268)

This is a troubling text. Paul seems to be telling slaves to remain in their slavery, not to be concerned about their condition of servitude; this would say to others that they should not struggle for the liberation of slaves. Of course, Paul believed the end of this world was right around the corner and such earthly conditions as slavery or mastership would be abolished in his lifetime. He was wrong … so how does his text speak to us today? ~ Paul’s counsel to remain “in whatever condition you were called” should not be used as a justification for not seeking better circumstances for oneself and an improvement of one’s circumstances. Indeed, it is debatable that Paul even gave that advice to stay in one’s “condition” or “situation”. It is rather more probable, it seems to me, that his counsel is to remain steadfast in one’s conversion (Greek kalesis = calling) to Christian faith and brotherhood resisting the pressures of one’s prior status – slave or master, Jew or Greek, married or single, whatever that condition or status may be – and this might even mean a change in that circumstance. I am so persuaded by the arguments of S. Scott Bartchy, Professor of Christian Origins and the History of Religion, Department of History, UCLA. He has examined how the Greek word kalesis meaning “calling”, “invitation” or “summons” – correctly translated as vocatione by St. Jerome in the Vulgate and as “calling” (or “called”) in the Authorized Version – came to be translated in later English versions as “condition”. His surprising (and probably correct) conclusion is to blame Martin Luther and the influence of his German translation! Bartchy has argued that it is certain that Paul did not teach enslaved Christ-followers to “stay in slavery.” Rather, he exhorted them (and us) to “remain in the calling in Christ by which you were called.” Quite the opposite of a passive quietism accepting of unjust social institutions, Paul’s exhortation is to an active faith repenting our own “blindness to human need and suffering and our indifference to injustice and cruelty.” (From the American BCP’s Ash Wednesday Litany of Penitence, p. 268)