Time away from the Irish (the language, not the people)….

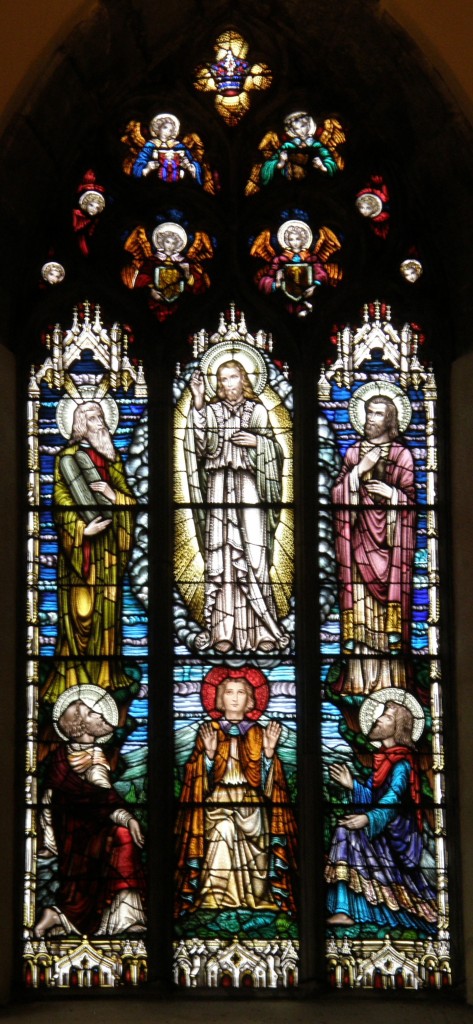

On Sunday, 24 July 2011, I left my teach loistín (“boarding house”) and drove the 32 km from An Cheathrú Rua to Galway to attend the Sung Eucharist at the Collegiate Church of St. Nicholas, a church which formerly (pre-Reformation) was the central church of the city. That distinction is now held by the Roman Catholic Cathedral, “The Cathedral of Our Lady Assumed into Heaven and St. Nicholas”. (How the BVM was assumed into St. Nicholas, I have no idea….) But St. Nicholas Collegiate Church, now an Anglican congregation of the Church of Ireland, continues to play a central role in the life of the city. The church has marvelous acoustics and is host to a variety of concerts, dramas, conferences, and other cultural and educational events throughout the year.

It also plays the role of providing a place of worship for visiting tourists who do not wish to attend a Roman Catholic Mass. The Sunday morning congregation, especially during the summer, is an aggregation of Irish Anglicans, Protestants of several sorts (many of whom do not speak English), and tourists with little or no religious background at all (some of whom, I sure, wander in on Sunday morning to see the historic church and get “trapped” in the service). Such was the congregation this Sunday.

I arrived in Galway about one hour before the service, so I went to a local café and had a cup of coffee. Thirty minutes before the service, I made my way to the church and found a seat – not difficult as there were very few people there. A church warden introduced himself and offered me a leaflet which included nearly the entire service with an insert of the hymn lyrics. On learning that I am a priest, he asked if I would read one of the lessons for the day, to which I assented.

One of the transepts of the church has been closed off with a partial glass screen and made into the choir room. The choir was practicing and their music filled the church – it was grand! It put one into a prayerful mood and prepared one to enter into worship.

About 15 minutes before the service was to start, a woman priest vested for the day began greeting those of us seated in the nave. She was to be the presider in the absence of the rector, who is on holiday this month.

The service started on time with a procession of crucifer, choir, and clergy. Although lay eucharistic ministers would later assist with the distribution of communion, they were not vested and did not process with the altar party. The placement of choir, clergy and altar assistant was interesting and, given that everything is moveable (and moves frequently for various events), I wondered if this is a standard arrangement or if they experiment regularly with different seating plans.

The service followed a fairly familiar pattern, more similar to the American church’s liturgy than were the Church of England services I experienced a couple of weeks ago, although as in the English church, the service began with a confession and absolution before the Gloria in Excelsis. Then there were the reading of the lessons, a sermon, a variant form of the Creed (sort of a Q-&-A format), prayers, the Peace, the offertory, the Great Thanksgiving, the distribution of Holy Communion (at stations, a central position for the Bread from the priest and four cups of Wine), the final blessing, the last hymn and the dismissal. It all followed a familiar and comforting pattern.

The lessons for the day were those of the Revised Common Lectionary – from the Hebrew Scriptures the story of Solomon asking God for the gift of wisdom; from the Epistles Paul’s assurance in Romans that nothing can separate us from the love of God; from the Gospel’s Jesus rapid fire mini-parables that the Kingdom of God is like a mustard seed, a buried treasure, a pearl of great price, a net thrown into the sea.

The homily admonished us to do as Jesus did and look for God’s reign in the ordinary things, the ordinary places, the ordinary people of our lives. In the course of the homily, the preacher compared the structure of Jesus’ delivery of the parables to that of the Psalms referring to the Hebrew practice of parallelism as “the rhyming of ideas.” That description stuck with me.

Later in the day, I relaxed with a book, The Elegant Universe by Brian Greene. In it, describing the findings of quantum mechanics as an introduction to a discussion of superstring theory, the author writes:

Even in an empty region of space – inside an empty box, for example – the uncertainty principle says that the energy and momentum are uncertain: They fluctuate between extremes that get larger as the size of the box and the time scale over which it is examined get smaller and smaller. It’s as if the region of space inside the box is a compulsive “borrower” of energy and momentum, constantly extracting “loans” from the universe and subsequently “paying” them back. But what participates in these exchanges in, for instance, quiet empty region of space? Everything. Literally. Energy (and momentum as well) is the ultimate convertible currency. E=mc2 tells us that energy can be turned into matter and vice versa. Thus if an energy fluctuation is big enough it can momentarily cause, for instance, an electron and its antimatter companion the positron to erupt into existence, even if the region was initially empty! Since this energy must be quickly repaid, these particles will annihilate one another after an instant, relinquishing the energy borrowed in their creation. And the same is true for all other forms that energy and momentum can take – other particle eruptions and annihilations, wild electromagnetic-field oscillations, weak and strong force-field fluctuations – quantum-mechanical uncertainty tells us the universe is a teeming, chaotic, frenzied arena on microscopic scales.

As I read this I was reminded of the first words of Holy Scripture:

In the beginning when God created the heavens and the earth, the earth was a formless void and darkness covered the face of the deep, while a wind from God swept over the face of the waters. Then God said, “Let there be light”; and there was light. And God saw that the light was good; and God separated the light from the darkness. God called the light Day, and the darkness he called Night. And there was evening and there was morning, the first day.

People ask why I read books on particle physics, quantum mechanics, and string theory for relaxation. I really don’t have a good answer, and I have to admit that a lot of what I read, though it fascinates me, goes right over my head! But, for reasons which are probably beyond anyone’s comprehension, including my own, my idea of relaxing reading is exactly the sort of stuff that bored me to tears 40+ years ago – physics books. In the new understandings of quantum mechanics, superstring theory, the multiverse speculation, and other work seeking the “theory of everything” (or “TOE” as Greene and others call it), I see science converging with religion. As microscopic physics gets “weirder” (Greene’s term, again), it seems to me it gets more theological, as well. Every so often a passage strikes, if you will, a theological cord. This was one of them … the description of even empty space as “teeming, chaotic, frenzied” seems to me to echo, to “rhyme” (to use the preacher’s term) with the idea of the writer of Genesis that “a wind from God” (the Holy Spirit) sweeps over creation. Numerous theologians have taken off from this Genesis account to assert that the Holy Spirit “enthuses” all things; that the wind from God blows through and within all of creation … even empty space. How great it is that science’s new understanding of empty space as “teeming” and “frenzied” rhymes with faith’s vision of empty space as filled with God’s wind!

In Sunday’s sermon, the preacher reminded us to seek God in the everyday stuff of life. As scientists probe the “weirdness” of the smallest dimensions of everyday stuff, I think they’re doing just that … seeking God. They may be calling it the search for the TOE, but to from my perspective it’s just a variation of the same search human beings have been on for millennia, the search for meaning.

And now … back to the Irish.