From the Psalms:

To the leader: according to The Deer of the Dawn. A Psalm of David.

(From the Daily Office Lectionary – Psalm 22, introduction – August 31, 2012)

Episcopalians reciting the Daily Office usually read the Psalms from The Book of Common Prayer, not from the Bible. This can cause some confusion about psalm verses because the versification and number of verses in the BCP differs from that in most Bible translations. The Psalter used in Anglican prayer books, including that of the Episcopal Church (until the 1979 book) was based on Miles Coverdale’s translation of the Bible which predated the Authorized (King James) version by nearly 80 years. The Coverdale Psalter had been used in all editions of The Book of Common Prayer, back to the first in 1549; while some editorial changes were made, the basic versification and numbering was maintained and this was continued in the 1979 version, which is a new translation but follows the tradition of Coverdale. Although not metrical, the translation was rendered with chanting in mind.

Episcopalians reciting the Daily Office usually read the Psalms from The Book of Common Prayer, not from the Bible. This can cause some confusion about psalm verses because the versification and number of verses in the BCP differs from that in most Bible translations. The Psalter used in Anglican prayer books, including that of the Episcopal Church (until the 1979 book) was based on Miles Coverdale’s translation of the Bible which predated the Authorized (King James) version by nearly 80 years. The Coverdale Psalter had been used in all editions of The Book of Common Prayer, back to the first in 1549; while some editorial changes were made, the basic versification and numbering was maintained and this was continued in the 1979 version, which is a new translation but follows the tradition of Coverdale. Although not metrical, the translation was rendered with chanting in mind.

I often take a look at the Psalms in the New Revised Standard Version (my preferred translation) to see what differences there might be. Among the things not included in the BCP’s Psalter are the introductory directions and titles found in the Psalms in the Bible, so it was the introduction to this evening’s Psalm that caught my attention today, particularly the image “the Deer of the Dawn.”

Not all of the Psalms have these introductory directions; in fact, the majority do not. Some of them are clearly musical instructions: “On stringed instruments” (Ps. 41, 54, 55, 61, and 67), “For flutes” (Ps. 5), “According to the Sheminith” (Ps. 6 and 12, apparently a reference to an eight-stringed instrument, or perhaps to a particular meter or octave); “For the harp” (Ps. 8 and 81 ). Fifteen of the Psalms (120-134) are titled “songs of ascent”, which may be a liturgical direction or a reference to particular festival usage. Several Psalms, like this one, have introductory authorship ascriptions: for example, many say “a psalm of David”; a few are labeled “a psalm of Asaph”.

A few psalms, like today’s, have lovely, poetic images in their introductory rubrics. Psalm 56 is labeled “concerning the silent dove afar off”; Psalms 45 and 69 are “for the lilies”; and Psalms 60 and 80 are described is “on the lily of the testimony.” Some believe these might be references to popular tunes to which the Psalm is to be sung, but no one really knows.

In any event, the image of the “deer of the dawn” caught me up today. Psalm 22 is familiar to most Christians because Jesus is said by Matthew and Mark to have quoted its first verse on the cross: “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” (Matt. 27:46; Mark 15:34) Psalm 22 is prescribed in the liturgy for Good Friday, and is sometimes recited during overnight prayer vigils on Maundy Thursday. But in none of those usages is the introductory rubric and this image, “the deer of the dawn,” mentioned; the introductory directions are not read as part of the liturgy.

I am not a hunter. I can safely say that I have never shot at a wild animal, ever. But I have many friends who are hunters and they tell me that dawn is the best time to go after deer. They tell that the earliest hours of the morning are when the deer are most active. Right around dawn is when they leave their beds and move to feeding areas. A spot near a trail between the two will give a hunter a good opportunity for an hour or two after sunrise. I believe this because our home backs up to a wooded easement a few miles in length and about 500 yards wide. I usually rise just about at dawn and as I get my first cup of coffee in the dim light of the kitchen, I can just make out the woods and any movement there may be. Frequently, a doe and one or more fawns or yearlings will be moving through the trees . . . often headed for our landscaping to munch on our hostas and other plants! (I have never shot at a wild animal . . . but I have been tempted.)

It seems somehow oddly appropriate that Jesus quoted from this Psalm and that it is used at late-night Maundy Thursday vigils and at Good Friday liturgies. Not simply because of Jesus’ words, nor because the Psalm includes such crucifixion-relevant language as

All who see me laugh me to scorn;

they curl their lips and wag their heads, saying,“He trusted in the Lord; let him deliver him;

let him rescue him, if he delights in him.”(and)

They stare and gloat over me;

they divide my garments among them;

they cast lots for my clothing.(Ps. 22:7-8, 17)

But because of this almost-forgotten introductory image “the deer of the dawn.”

We are told in Mark 14 and Matthew 26 that after the passover supper, Jesus took Peter, James, and John to the garden at Gethsemane and spent some time in prayer. It has always seemed to me that this must have stretched over several hours and that his betrayal and arrest must have occurred in the early morning hours. The Temple authorities, soldiers, and police who came to get him chose a time and a place not unlike a deer hunter, a time when they would have the best opportunity to find him, the best shot to take him. Jesus is “the Lamb of God” but it seems he is also “the deer of the dawn,” the innocent taken in the quiet of the new day’s early hours, the blameless bagged at sunrise.

====================

Father Funston is the rector of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Medina, Ohio.

Judaism is not a missionary religion. It is, however, a proselytic religion. This means that Jews don’t go looking for converts, but those who come to them interested in becoming Jews are instructed and initiated; these initiates are called proselytes. Cornelius might have become a proselyte, but we know that he was not because if he had been, Peter would have had no issues with seeing him, meeting him, eating with him. Peter did have those issues initially, but then was shown the vision of unclean animals which he was told to eat. Peter interpreted that vision to mean that he should not treat non-Jews as unclean; it was the beginning of the Jewish Christian church welcoming non-Jews (“Gentiles”) as members.

Judaism is not a missionary religion. It is, however, a proselytic religion. This means that Jews don’t go looking for converts, but those who come to them interested in becoming Jews are instructed and initiated; these initiates are called proselytes. Cornelius might have become a proselyte, but we know that he was not because if he had been, Peter would have had no issues with seeing him, meeting him, eating with him. Peter did have those issues initially, but then was shown the vision of unclean animals which he was told to eat. Peter interpreted that vision to mean that he should not treat non-Jews as unclean; it was the beginning of the Jewish Christian church welcoming non-Jews (“Gentiles”) as members. The picture of Jesus getting advice from his brothers just tickles me. John makes such a deal of it (while pointing out that his brothers did not believe in him – as the Messiah, I suppose – at the time). It seems so at odds with John’s otherwise oh-so-perfect, oh-so-divine Jesus!

The picture of Jesus getting advice from his brothers just tickles me. John makes such a deal of it (while pointing out that his brothers did not believe in him – as the Messiah, I suppose – at the time). It seems so at odds with John’s otherwise oh-so-perfect, oh-so-divine Jesus!

The Jews, John tells us, disputed among themselves as Jesus was delivering the lengthy dissertation on bread from which these statements come. Earlier he had introduced this idea that his flesh was bread to be eaten by his followers: “I am the living bread that came down from heaven. Whoever eats of this bread will live for ever; and the bread that I will give for the life of the world is my flesh.” (v. 51) The very idea of consuming human flesh is off-putting, even disgusting, and would have been extremely objectionable to the Jews; no wonder they grumbled and mumbled, complained and disputed. Even as a metaphor, the statement demands a lot from Jesus’ followers!

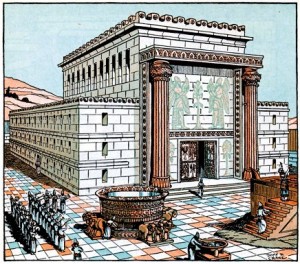

The Jews, John tells us, disputed among themselves as Jesus was delivering the lengthy dissertation on bread from which these statements come. Earlier he had introduced this idea that his flesh was bread to be eaten by his followers: “I am the living bread that came down from heaven. Whoever eats of this bread will live for ever; and the bread that I will give for the life of the world is my flesh.” (v. 51) The very idea of consuming human flesh is off-putting, even disgusting, and would have been extremely objectionable to the Jews; no wonder they grumbled and mumbled, complained and disputed. Even as a metaphor, the statement demands a lot from Jesus’ followers! On the cover of our worship bulletin this morning is a depiction of King Solomon’s Temple. It’s an artist’s rendering of someone’s reconstruction of the Temple based on the description of its construction in the Old Testament record. Our first reading today (from the First Book of Kings), as long as it was, is just a small part of the dedicatory prayer that King Solomon offers when the Temple is finished and consecrated.

On the cover of our worship bulletin this morning is a depiction of King Solomon’s Temple. It’s an artist’s rendering of someone’s reconstruction of the Temple based on the description of its construction in the Old Testament record. Our first reading today (from the First Book of Kings), as long as it was, is just a small part of the dedicatory prayer that King Solomon offers when the Temple is finished and consecrated. Where were you on July 20, 1969? In July of 1969 I was living in a boarding house and studying in Florence, Italy. The boarding house or pensione in which I lived, Pensione Frati, did not have a television. My landlord, Colonello Roberto Frati, arranged for me and the other Americans living there to go to his sister-in-law’s home where we could watch Neil Armstrong’s and Buzz Aldrin’s moon landing on her TV – this great big box of a television set with a tiny black-and-white screen. We all gathered around that box peering into that tiny screen listening to the Italian news commentators and struggling to hear the American commentary behind them. I’m sure that when we heard of Commander Armstrong’s death we all thought about wherever we were on that day at that moment when he stepped out of the lunar lander and became the first human being to walk on another world.

Where were you on July 20, 1969? In July of 1969 I was living in a boarding house and studying in Florence, Italy. The boarding house or pensione in which I lived, Pensione Frati, did not have a television. My landlord, Colonello Roberto Frati, arranged for me and the other Americans living there to go to his sister-in-law’s home where we could watch Neil Armstrong’s and Buzz Aldrin’s moon landing on her TV – this great big box of a television set with a tiny black-and-white screen. We all gathered around that box peering into that tiny screen listening to the Italian news commentators and struggling to hear the American commentary behind them. I’m sure that when we heard of Commander Armstrong’s death we all thought about wherever we were on that day at that moment when he stepped out of the lunar lander and became the first human being to walk on another world. Wow! Does this look familiar? The second chapter of Job begins with a scene nearly identical to that which we considered yesterday. Satan (with other heavenly beings) presents himself in the heavenly throne room and, once again, God and Satan have a conversation about Job and, once again, the bet is made. In fact, it’s sort of “double down” time! Yesterday, I argued that although the Book of Job is fiction it (like the other forms of literature found in Holy Scripture) embodies truth.

Wow! Does this look familiar? The second chapter of Job begins with a scene nearly identical to that which we considered yesterday. Satan (with other heavenly beings) presents himself in the heavenly throne room and, once again, God and Satan have a conversation about Job and, once again, the bet is made. In fact, it’s sort of “double down” time! Yesterday, I argued that although the Book of Job is fiction it (like the other forms of literature found in Holy Scripture) embodies truth. A later selection from the Book of Job was called up by the Sunday Eucharistic Lectionary several weeks ago. In my sermon I said to the congregation that the Book of Job is fiction (which it is). You should have seen the look on one of my parishioners’ face! There’s a fellow in the congregation who is, shall we say, conservative with regard to the Bible. While I don’t believe he actually considers the Bible to be the inerrant word of God per se, he’s pretty sure that it is to be taken with the highest degree of certainty and words like “myth” or “fiction” applied to Scripture are not to his liking. I swear I thought he might have an apoplectic fit right there in his pew! But let’s be honest: do we really think that God and Satan are engaged (or have ever been engaged) in a game of chance involving the lives of human beings?

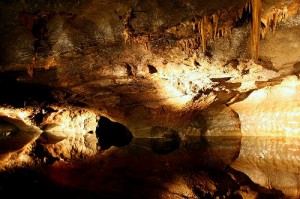

A later selection from the Book of Job was called up by the Sunday Eucharistic Lectionary several weeks ago. In my sermon I said to the congregation that the Book of Job is fiction (which it is). You should have seen the look on one of my parishioners’ face! There’s a fellow in the congregation who is, shall we say, conservative with regard to the Bible. While I don’t believe he actually considers the Bible to be the inerrant word of God per se, he’s pretty sure that it is to be taken with the highest degree of certainty and words like “myth” or “fiction” applied to Scripture are not to his liking. I swear I thought he might have an apoplectic fit right there in his pew! But let’s be honest: do we really think that God and Satan are engaged (or have ever been engaged) in a game of chance involving the lives of human beings? Psalm 130 is one of the seven “pentitential psalms” of the church (Psalms 6, 32, 38, 51, 102, 130, and 143), a tradition that stretches back to the Sixth Century if not earlier. It is also one of the “songs of ascents” (Psalms 120-134) that are believed to have been sung by pilgrims making their way up to Jerusalem or possibly when climbing up the Temple Mount for festival celebrations. Somehow it strikes me as both odd and poignant that a song or poem beginning “Out of the depths” is called a song of “ascent” – from the deepest sloughs of despond the poet calls out the Highest. Ascent, indeed!

Psalm 130 is one of the seven “pentitential psalms” of the church (Psalms 6, 32, 38, 51, 102, 130, and 143), a tradition that stretches back to the Sixth Century if not earlier. It is also one of the “songs of ascents” (Psalms 120-134) that are believed to have been sung by pilgrims making their way up to Jerusalem or possibly when climbing up the Temple Mount for festival celebrations. Somehow it strikes me as both odd and poignant that a song or poem beginning “Out of the depths” is called a song of “ascent” – from the deepest sloughs of despond the poet calls out the Highest. Ascent, indeed!