====================

This sermon was preached on the Patronal Feast Sunday of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Medina, Ohio, where Fr. Funston is rector. It was the Sunday of the Annual Parish Meeting and, as part of the service, a newly built Gallery addition to the parish’s fellowship hall was dedicated.

(The lessons for the day were for the Conversion of St. Paul from the Episcopal Church’s sanctoral calendar: Acts 26:9-21; Galatians 1:11-24; Psalm 67; and Matthew 10:16-22. These lessons can be read at The Lectionary Page.)

====================

A few decades ago when I was studying law I was introduced to the term “officious intermeddler.” In law, an officious intermeddler is someone who, on their own and without any authority either by invitation or pre-existing legal duty, interjects himself into the affairs of another, and then seeks some sort of recompense for doing so. That pretty much describes young Saul of Tarsus and at least his initial quest to rid Judaism of the followers of Jesus of Nazareth. He was simply a rabbinic student, not any sort of priest or religious official when he began his crusade against Peter and James and the others. I don’t think he was doing it for money, but I do think he might have been looking for a pay-off in the form a religious reputation; if he was successful, he would become a powerful rabbi among the Jewish the people.

Saul was born and raised in the Greek city of Tarsus and apparently received a good education both in orthodox Judaism and in Greek philosophy; Tarsus was a center of Stoic teaching and we see a good deal of Stoicism in the letters he wrote after becoming a Christian missionary. While still fairly young, Saul was sent to Jerusalem to receive rabbinic instruction at the Hillel school under Gamaliel, one of the most noted rabbis in Jewish history. This would have exposed the young rabbinic student to a broad range of classical literature, philosophy, and ethics. Not a lot more is known of his background before he decided to make a name for himself dealing with the pesky proclaimers of what he considered to be a pernicious heresy.

Until the destruction of the Jerusalem Temple in 70 A.D. the followers of Jesus of Nazareth were simply one of many subsets of Judaism; there were few, if any, Gentile followers of Jesus and those Gentiles who wanted to be a part of the new group were required to convert to Judaism before being allowed to join the Jesus group. Judaism at the time was much like Christianity is today; there were different “schools,” similar to our denominations.

We are familiar from the Gospel stories with the Pharisees and the Sadducees, two of the competing versions of the faith; we may also be familiar with the Essenes who were part of the mix. In addition, influential rabbis had their groups of followers: John the Baptizer had had his disciples; Gamaliel had his; perhaps Nicodemus, who became a secret follower of Jesus, had his own school; and, of course, Jesus had had his. On the major feasts and liturgical days, all Jews would observe the Temple rituals together, but for their sabbath observance and instruction they would go to the synagogue which adhered to the school they found most convincing, or where their rabbi taught. They recognized each other as Jews; they just didn’t agree on some particulars. No big deal. And, usually, when their rabbi passed away, their group disbanded.

Except for the disciples of Jesus, those people who followed what they called “the Way.” Their rabbi was dead; the whole city had seen him crucified. But unlike the followers of other dead rabbis, these people didn’t disband; they claimed that their rabbi was still alive and they still met to proclaim his teachings. They even went so far as to suggest that he was divine; they were claiming that he had ushered in a new kingdom of God. In the Jewish council, the Sanhedrin, some sought to have them kicked out of the temple, but Saul’s own teacher, Gamaliel, defended them. The Book of Acts reports his words to the Sanhedrin:

Fellow Israelites, consider carefully what you propose to do to these men. For some time ago Theudas rose up, claiming to be somebody, and a number of men, about four hundred, joined him; but he was killed, and all who followed him were dispersed and disappeared. After him Judas the Galilean rose up at the time of the census and got people to follow him; he also perished, and all who followed him were scattered. So in the present case, I tell you, keep away from these men and let them alone; because if this plan or this undertaking is of human origin, it will fail; but if it is of God, you will not be able to overthrow them — in that case you may even be found fighting against God! (Acts 5:35-39)

Apparently Saul did not agree with his teacher. He became an officious intermeddler, a self-appointed — that’s really what “officious” means — a self-appointed policeman protecting the purity of the Temple; he was going to get that Jesus crowd kicked out. In his letter to the Galatians he would confess that prior to his conversion he “was violently persecuting the church of God and was trying to destroy it.” (Gal. 1:13) It is in the description of the martyrdom of the first deacon, Stephen, that we first encounter Saul in the New Testament. We don’t know whether Saul was an instigator of the events that led to Stephen’s death, but we know that he was there.

The 7th Chapter of Acts tells us that Stephen preached a sermon in the presence of the Temple council, an admittedly rather inflammatory homily, after which “with a loud shout [those present] rushed together against him. Then they dragged him out of the city and began to stone him; and the witnesses laid their coats at the feet of a young man named Saul.” (Acts 7:57-58) We are told that “Saul approved of their killing him.” (Acts 8:1) Saul didn’t take part, really; he just stood at the road side looking on.

After that, Saul became more and more openly and actively involved in the persecution of the Jesus movement, “ravaging the church by entering house after house; dragging off both men and women, he committed them to prison.” (Acts 8:3) Eventually, this officious intermeddler received his remuneration — recognition and ratification of his activities by the high priest from whom he sought, and received, letters of warrant empowering him to go to Damascus, “arrest any who belonged to the Way, men or women, [and] bring them bound to Jerusalem.” (Acts 9:2) It was while journeying to Damascus that the events he described to King Agrippa in the reading we heard this morning occurred. It was while on that road to Damascus that the truth of the Gospel of Jesus Christ, which he had been unable to see, was revealed to him. As he wrote to the Galatians, God “was pleased to reveal his Son to me, so that I might proclaim him among the Gentiles.” But in the experience, we are told in Acts, something like scales covered his eyes as if symbolizing the blindness of heart he had suffered, and until he learned the fullness of the Gospel he was unable to see.

I will return to Saul and his conversion in a moment, but before I do I want to review a little bit of our parish history. So for the moment, let’s put Saul aside but keep in mind his story, especially those scales that eventually fell from his eyes.

We are beginning the 197th year of the life of St. Paul’s Parish. Founded in 1817 in Weymouth, the congregation moved to this location in the 1830s. After about 50 years in a wooden Greek revival structure, in 1884 the congregation built the stone church in which we are worshiping today. When weather permitted they would gather for after church fellowship on the lawn, fully open to their neighbors’ view and could invite the neighbors to take part.

In 1903, they built the Parish House in which our present day Parish Hall, kitchen, and dining room are located. It was a separate structure with one of those wide and inviting Victorian front porches. When the congregation gathered after church for fellowship, education, or other activities, they came and went through the front doors of the church, onto that veranda, and in and out the front door of the Parish House, again fully visible to their neighbors whom they continued to invite to participate.

Another fifty or so years later, the congregation built Canterbury House and linked it together with the Parish House and the church building with the concourse that came to be known simply as “the hallway.” The hallway replaced the Victorian veranda with fortress-like stone wall; it cut off the neighbors’ view of the congregation’s comings and goings, and blocked the neighbors’ appreciation of the church’s fellowship and other activities. The hallway incorporated a new entryway off the driveway leading to a parking lot that was built at the rear of the church property, and it was through those doors (and other doors at the rear of the Parish House) that members began entering the church building. The front doors of the Parish House and the church building fell into disuse, and the parishioners stopped invited the neighbors.

If anything was going on inside the Episcopal Church, you couldn’t tell it from the street. Stained glass windows on the church building, opaqued windows on the hallway, that imposing stone wall, and a set of large red doors which could not be opened from the outside blocked the public’s view of whatever it was the Episcopalians were doing.

Interestingly enough, the Episcopalians couldn’t see out, either. But until the new Gallery was built, and the sunshine and view of the street let in, we had failed to notice that! We were simply unaware that when we were inside this church’s physical plant we were visually cut off from the world around us; we just didn’t notice. We sat at here at the road side, but we were disconnected from the world going by on the major trafficway outside.

To be sure, there was plenty going on inside the church. Things were booming. It was the 1960s and the World War II and Korean War generations were coming to church, raising their children, participating in church clubs, holding fundraisers, even reaching out in overseas mission. The Episcopal Church was an active place . . . you just couldn’t tell it from the street.

And that story was true for the Episcopal Church as a whole, as a national institution, as well. We were pretty much a self-contained and self-reliant denomination. Someone not born into the Episcopal Church might occasionally wander through our doors, become fascinated with our peculiar style of being Christian, and join us, but we didn’t go out and encourage that sort of thing. Billy Graham and people like him might go out and evangelize and try to convert people, but that just wasn’t our style. We were doing quite well behind our stone walls and opaque windows, and our understanding of evangelism was that it was something other people did. After all, as one grand dame of the era is supposed to have put it, “Everyone who should be an Episcopalian already is one.” The world outside the Episcopal Church didn’t know much about us, and we were fine with that.

Then came the 1970s and things began to change. Social change was in the air both in the secular world and in the church. It was not comfortable. Women started suggesting that some of them might have a call to ordained ministry, and some of our best theologians supported them and agreed; behind our stone walls and opaque windows we were fighting like cats and dogs about it. The outside world only got a glimpse of it when a few very angry people threw open the red doors and stormed out, proclaiming themselves to be the only real Anglican Christians and the rest of us heretics, doomed to Hell. We got a lot of press, but not the kind of attention we really wanted. As soon as we could, we closed the red doors and regained our composure behind our stone walls.

But then, not very many years later, the General Convention approved a new Prayer Book. The process of revision had been going on for nearly 20 years but most of us hadn’t been paying attention. When the new book was approved in 1976 and then ratified in 1979 it seemed to many that the church was being completely overturned. The outside world got another glimpse of us when some more very angry people threw open the red doors and stormed out, proclaiming that they used the only real Anglican Prayer Book and that the rest of us were heretics, damned to Hell. Again, we got a lot of press, but once again it was not the kind of attention we really wanted. As soon as we could, we got back behind our stone walls.

Things were quiet for a while, but then the people of the Diocese of New Hampshire decided to elect their Archdeacon to be their Bishop and, horror of horrors, it turned out (they had known all along) he was a homosexual living in a committed, long-term relationship with another man. All hell broke loose behind our stone stone walls and opaque windows as we dealt with that. The arguing got so loud that the neighbors could hear us and, again, a group of very angry people threw open the red doors and stormed out, proclaiming themselves to be the only real Anglican Christians and the rest of us heretics, definitely headed straight to Hell. Again, we got a lot of press, and again we tried to regain our composure behind our stone walls. But we couldn’t because, finally, we started noticing something.

We noticed that the church was getting smaller. Fewer people were attending. Fewer children were enrolling in Sunday School. Fewer teens were coming to EYC meetings. Fewer dollars were getting deposited into the bank. And we decided, because we had gotten out of the habit of looking outside, that it was because of something we had done — it was because we ordained women; it was because we’d changed the Prayer Book; it was because we had a gay bishop. We were wrong, however. If we hadn’t been shut up behind our stone walls and opaque windows, we might have noted that the same thing — lower attendance, fewer children, fewer teens, less income — was happening to the Lutherans, and the Methodists, and the Presbyterians, and also to non-church groups like the Masons, and the Elks, and local bowling leagues. There was a societal change going on and, unable to see out through our stone walls and opaque windows, we couldn’t see it. We couldn’t figure out why the church was leaking membership because we weren’t looking in the right place.

And while all of that was going on . . . every time it rained there was water pouring into the church basement. Every time there was a heavy snow and it melted, there was water pouring into the basement. We got used to seeing buckets in the entryway and water stains on the basement ceiling because we couldn’t figure out where the leak was and we couldn’t figure out how to stop it. Physically, as well as metaphorically, we couldn’t figure out why the church was leaking.

We’ve learned a thing or two in the Episcopal Church in the last decade. We’ve learned that the church fails to grow not because of our internal failures; it fails to grow because of our external failures. The church has failed to grow because we have sequestered ourselves behind stone walls and opaque windows, and have failed to engage with our neighbors, who cannot see what we are doing and to whom we have not been paying attention. Out of this have come movements and experiments to get our denomination back out, on the other side of our stone walls, back into public engagement.

We are seeing new ministries such as “Church Without Walls,” an experiment in the Jacksonville, Florida, which calls people from all walks of life into partnership with “the least of these.” “Church Without Walls” describes itself as “a community of presence made up of individuals looking for the spiritual companionship and connection that give meaning to life.” The community seeks to welcome everyone — the homeless and the affluent, the addicted and those in recovery, the churched and the un-churched, the spiritual but not religious, the believer, the doubter and the seeker. They are grounded in the reality that “by opening ourselves to strangers, the despised or frightening or unintelligible other, we will see more and more of the holy.” (Description from the Diocese of Florida website.) And similar communities are being created in San Jose, California; Springfield, Pennsylvania; Bentonville, Arkansas; Milwaukee, Wisconsin; and elsewhere.

We are seeing experiments in public liturgy such as “Ashes to Go” — an effort to give people an opportunity to receive the mark of repentance and encourage them to give thought to their spiritual lives without requiring them to attend a full Ash Wednesday service. The first such public imposition of ashes was offered by the cathedral in Chicago, Illinois, and has since been offered in a variety of locations throughout the country, including some places here in Ohio.

What the Episcopal Church has learned through these and other programs is that we have to tear down the stone walls and break out the opaqued windows that have separated us from our neighbors. When we do that and the church again engages with the world around it, the leaking stops; the church begins to grow again. Like Saul, after the scales fell his eyes when he was baptized and took the name Paul, by which we know him better, we have seen the truth and know that we, too, are “to open [the eyes of those around us] so that they may turn from darkness to light and from the power of Satan to God, so that they may receive forgiveness of sins and a place among those who are sanctified by faith in [Jesus].” (Acts 26:18)

And here we are in a congregation that has quite literally removed its stone wall and its opaqued windows, whose neighbors can now see clearly what is going on in the Episcopal Church, and who can see our neighbors even when we are inside our building. We have opened ourselves to engagement with the world around us. We are not a “Church Without Walls,” but we have become a church that lives in glass house . . . the neighbors can see in and we’d better make sure that what they see is good stuff!

If you have picked up a copy of the 2014 Annual Journal, you will see some interesting data. We are at the beginning a new period of growth. For 2013 we have a mixed bag of membership statistics: 21 new members joined the congregation by baptism, confirmation, reception or transfer; we had larger congregations for both Easter and Christmas services; we had more Sunday services. On the other hand, our average attendance is down slightly. The task before us is to grow both in membership and active commitment. The foundation is here. For 2014, we have a 7% increase in the number of pledging households; total pledging is up (compared to last year) by over 4%. We have a committed membership.

Our outreach to the community is strong. The Free Farmers’ Market, our food pantry, assisted 5,333 individuals during the past year, distributing nearly 50,000 pounds of food. The volunteer effort to accomplish that is phenomenal, and all members of the coordinating committee and all the volunteer workers are to be commended. Our support of the regional Battered Women’s Shelter expanded this year as, in addition to the regular monthly collection of supplies, our new Lenten Rose Chapter of the Daughters of the King oversaw a special drive for personal hygiene items and, through the effort of our Senior Warden, we provided several dozen stuffed toys to the children sheltered there. Our youth group also continued their annual tradition of making and giving away teddy bears to needy children at Christmas time.

Outreach of a different sort is exercised in the monthly Brown Bag Concert program which is entering its seventh year. Our music director is to be commended for the excellent work she does in recruiting performers and hosting our guests at those events. Because of the construction of the new Gallery, we did not hold any “Fridays at St. Paul’s Concerts,” but we are looking forward to the return of that program as early as this coming May when the chamber ensemble of the Cleveland Philharmonic Orchestra will be performing in this sanctuary.

Fellowship continues with the men’s breakfasts, the Episcopal Church Women, the new Daughters of the King chapter, the Sunday morning breakfast group, and the return this month of the Foyer Group dinner program. Christian education for children and youth is going strong with Godly Play and the Episcopal Youth Community; many of our EYC members are recognized leaders in the diocesan youth programs and are to be commended for that. Many of them are not here today because they have spent the weekend in training to lead the next “Happening” retreat for young people. For adults we have a regular weekly bible study and, starting last September, an Education for Ministry seminar group going strong.

By nearly every measure, this is a vibrant and lively parish. This church is no longer leaking! It is not leaking rain water into the basement; it is not leaking membership. Both the literal and the figurative stone walls have fallen away, like the scales that fell from St. Paul’s eyes, and the vibrancy and life of this parish is visible for all to see and for all to be invited into.

We were blinded and confused by our stone walls and our opaque windows, whether figurative or literal, but in the end, we know that we are called, as Paul was, to share the wonderful news that the risen Jesus, the Son of God, is Messiah and his kingdom is here now. Our experience of engaging in the Inviting the Future Project and building our beautiful new Gallery, is our “ Damascus Road ” experience. A new day for St. Paul’s Parish is shining through the windows of the Gallery and our calling is to insure that the neighbors — who can see us once again, just as they could in 1884 and in 1903 and in every year up to 1960, and (more importantly) whom we can now see — our calling is to insure that they can see the kingdom of God shining out, that they are invited to come into it.

Let us pray:

Give us grace, O Lord, to answer readily the call of our Savior Jesus Christ and proclaim to all people the Good News of his salvation, that we and the whole world may perceive the glory of his marvelous works; who lives and reigns with you and the Holy Spirit, one God, for ever and ever. Amen. (Collect for the 3rd Sunday after Epiphany)

====================

A request to my readers: I’m trying to build the readership of this blog and I’d very much appreciate your help in doing so. If you find something here that is of value, please share it with others. If you are on Facebook, “like” the posts on your page so others can see them. If you are following me on Twitter, please “retweet” the notices of these meditations. If you have a blog of your own, please include mine in your links (a favor I will gladly reciprocate). Many thanks!

====================

Father Funston is the rector of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Medina, Ohio.

These few verses are the end of the story of Jesus’ encounter with the Samaritan woman at Jacob’s well which led to his two-day sojourn in the Samaritan city of Sychar. Whenever I have heard this story preached (and, I confess, when I have preached it myself), the emphasis seems always to be on the Lord’s daring to speak with a woman, and a Samaritan woman, at that! The focus is his unconventionality, his willingness to step outside the Law, and his abrogation of ethnic and sexual norms. We are told how extraordinary this encounter was.

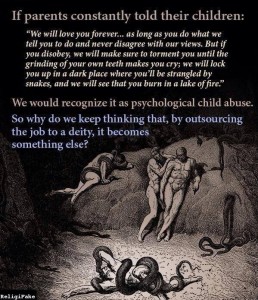

These few verses are the end of the story of Jesus’ encounter with the Samaritan woman at Jacob’s well which led to his two-day sojourn in the Samaritan city of Sychar. Whenever I have heard this story preached (and, I confess, when I have preached it myself), the emphasis seems always to be on the Lord’s daring to speak with a woman, and a Samaritan woman, at that! The focus is his unconventionality, his willingness to step outside the Law, and his abrogation of ethnic and sexual norms. We are told how extraordinary this encounter was. Making the rounds of Facebook these days is an anti-religious meme which basically equates religious teaching to child abuse. It says:

Making the rounds of Facebook these days is an anti-religious meme which basically equates religious teaching to child abuse. It says: The musical Godspell debuted in 1971 (my junior year in college); in it, Christ is portrayed as a clown. Whether it was an expression of or the catalyst for the phenomenon of offering clown eucharists as an edgy, avant-garde presentation of the Christian Mysteries, I really don’t know. The two are inextricably linked in my memory.

The musical Godspell debuted in 1971 (my junior year in college); in it, Christ is portrayed as a clown. Whether it was an expression of or the catalyst for the phenomenon of offering clown eucharists as an edgy, avant-garde presentation of the Christian Mysteries, I really don’t know. The two are inextricably linked in my memory. I took yesterday “off” and stayed away from church-related things. I read the Daily Office, of course, and thought about St. Stephen, Deacon and Martyr. I even thought about writing one of these meditations, but never got around to it. I really did nothing “religious” . . . until dinner time when I had a previously scheduled a meeting with a small group of parishioners.

I took yesterday “off” and stayed away from church-related things. I read the Daily Office, of course, and thought about St. Stephen, Deacon and Martyr. I even thought about writing one of these meditations, but never got around to it. I really did nothing “religious” . . . until dinner time when I had a previously scheduled a meeting with a small group of parishioners. I’m following a thread on a friend’s Facebook page about the future of the “institutional church,” by which I think the various participants mean their several denominations. (We are Episcopalians, Methodists, Presbyterians, Lutherans, etc., all of whom seem primarily to identify as Christians and only secondarily with the variety of polities, theologies, liturgical styles, and so forth we each prefer.) I suggested in the discussion that creating institutions is in the very nature of human beings; we create them, criticize them, tear them down, reform them, and recreate them, but we never escape from them. Another participant in response said, “I do not create community.”

I’m following a thread on a friend’s Facebook page about the future of the “institutional church,” by which I think the various participants mean their several denominations. (We are Episcopalians, Methodists, Presbyterians, Lutherans, etc., all of whom seem primarily to identify as Christians and only secondarily with the variety of polities, theologies, liturgical styles, and so forth we each prefer.) I suggested in the discussion that creating institutions is in the very nature of human beings; we create them, criticize them, tear them down, reform them, and recreate them, but we never escape from them. Another participant in response said, “I do not create community.” What is a church building? It’s a holy place. It’s a place where people gather to worship. It’s a place where people encounter God. It’s a place where God’s people enjoy one another’s company. It’s a place where people get married, where babies are baptized, where funerals are held, where memories are made and lives remembered. It’s a place where the stories of faith are told and retold. It’s a place we teach and it’s a place where we learn.

What is a church building? It’s a holy place. It’s a place where people gather to worship. It’s a place where people encounter God. It’s a place where God’s people enjoy one another’s company. It’s a place where people get married, where babies are baptized, where funerals are held, where memories are made and lives remembered. It’s a place where the stories of faith are told and retold. It’s a place we teach and it’s a place where we learn. OK. I’ll acknowledge and admit that there may have been good reason for Moses to lay down this law for his people as they were preparing to enter the Promised Land. He was concerned that they maintain their identity as the Hebrews, the People of the God of Sinai, and if they had taken on the gods or worship of the people they were conquering that might have been difficult. That he put these words into the mouth of God, however, is very problematic. It was a disservice to later generations and it has played havoc with ecumenical and interfaith relations in the modern era.

OK. I’ll acknowledge and admit that there may have been good reason for Moses to lay down this law for his people as they were preparing to enter the Promised Land. He was concerned that they maintain their identity as the Hebrews, the People of the God of Sinai, and if they had taken on the gods or worship of the people they were conquering that might have been difficult. That he put these words into the mouth of God, however, is very problematic. It was a disservice to later generations and it has played havoc with ecumenical and interfaith relations in the modern era. A few days ago an ordained colleague posted this status to Facebook:

A few days ago an ordained colleague posted this status to Facebook: I wonder if Jesus had this prophecy in mind when he called Andrew and Peter and said to them, “Follow me, and I will make you fish for people.” (Matt. 4:19)

I wonder if Jesus had this prophecy in mind when he called Andrew and Peter and said to them, “Follow me, and I will make you fish for people.” (Matt. 4:19)