Today, 9 July 2011, I walked the hills of southeastern England visiting two fascinating sites that may date back as many as 5,000 years!

First I visited the village of Uffington, Oxfordshire, and the hill south of town on which one finds a massive depiction in white chalk of a horse. I tried to take a picture of it, but from ground level that is very difficult to do and (on this day) the site was crawling with several hundred early elementary school students on school outings. So here’s a picture from Wikicommons:

I walked up to the area where the head of the horse is seen in this picture. It was an overcast and hazy but warm day – a good thing because it was also very breezy. It was about a mile or so walk up the hill from the car park via the Ridge Path, which took me through the Uffington Castle, which isn’t what you think it is at all … not a castle in the medieval sense. Uffington Castle is all that remains of an early Iron Age hill fort. It is composed of two circular earth berms (with a circular ditch between them) surrounding about 32,000 square meters (nearly 8 acres). There is an entrance in the eastern portion, near the White Horse and another at the south (through which I entered). An entrance in the western side was apparently blocked up a few centuries after it was built. I was able to take a picture of the “castle” (although it doesn’t look like much). This picture is taken from the eastern entrance of the southeastern quadrant; the southern entrance can be seen at the right of the picture.

As you can see, the White Horse is a highly stylised prehistoric hill figure, 110 m long (374 feet), formed from deep trenches filled with crushed white chalk. The figure is believed, and scientific tests have shown it, to date back some 3,000 years, to the Bronze Age. The purposes of its creators is completely unknown. It is not of Celtic origin, but G.K. Chesterton used it as the setting for part of his Catholic allegorical and poetic retelling of the story of the Saxon king Alfred the Great, who defeated the invading Danes in the Battle of Ethandun in 878, which is entitled The Ballad of the White Horse.

Before the gods that made the gods

Had seen their sunrise pass,

The White Horse of the White Horse Vale

Was cut out of the grass.Before the gods that made the gods

Had drunk at dawn their fill,

The White Horse of the White Horse Vale

Was hoary on the hill.Age beyond age on British land,

Aeons on aeons gone,

Was peace and war in western hills,

And the White Horse looked on.For the White Horse knew England

When there was none to know;

He saw the first oar break or bend,

He saw heaven fall and the world end,

O God, how long ago.

As retold by Chesterton, Alfred and his Saxons set out from the White Horse and Alfred gathers there three great chieftains, Mark a Roman, Eldred the Franklin who is a Saxon, and Colan who is a Celt. In describing Colan, Chesterton includes these priceless lines:

For the great Gaels of Ireland

Are the men that God made mad,

For all their wars are merry,

And all their songs are sad.

After visiting the Uffington site, I went to Avebury to see the largest “henge” in Britain (possibly the largest man-made earthwork of its kind in all of Europe). A henge (the word is derived from Stonehenge and was coined in the mid-20th Century) is an earthen berm circular with an interior circular ditch. Because the ditch is on the inside, not the outside, of the berm, henges are not considered to be defensive fortifications. One scholar, however, has suggested that they are defensive in that he believes they were built to contain something and protect those outside from what was inside – and what was inside was divine energy. The Avebury henge contains many standing stones that are laid out in peculiar formations, some circles, some straight lines, some curving formations not forming full circles. Here are some photos of the standing stones.

This is a map (from Wikimedia) showing the Avebury henge and the position of the standing stones (and theoretical stones completing the circles). It does not show the Avebury village buildings which have been built within the henge. The henge has a circumference of about 3/4 of a mile.

I am intrigued by the idea that because the ditch and bank face inward, in the opposite order that they would be placed in a defensive ring fort, something “dangerous” or “powerful” was understood to be inside the enclosure. The proposal is that henges were designed mainly to enclose ceremonial sites seen as “ritually charged” and therefore dangerous to people, that whatever took place inside the enclosures was intended to be separate from the outside. In other words, the henge may have been a means by which neolithic society set aside “sacred space” in much the same way that modern human beings do with churches, mosques, temples, and so forth.

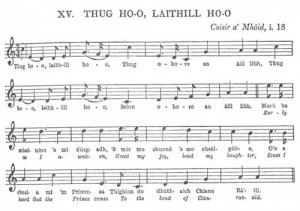

The hymn An Aluinn Dún (The Heavenly Habitation), which was set out in an earlier post, is about sacred space (heaven, particularly). The Celts and the Gaels have a special sense about sacred places; they marked them, but did not attempt to set them off or guard against them in the way henges seem to do. In fact, holy caves and holy wells were understood to be places of refreshment, “thin places” between our world and the spiritual realm, not something to be feared, but something to enjoy, somewhere to grow closer to God.

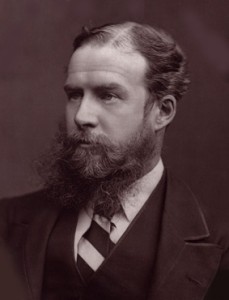

I had no idea who John Lubbock was, although I now know that I certainly should have. He was a Victoria era banker with many side interests, and the First Baron Avebury. He also was a good friend of Charles Darwin, whose hometown of Shrewsbury, Shropshire, I will be visiting in just under two weeks.

I had no idea who John Lubbock was, although I now know that I certainly should have. He was a Victoria era banker with many side interests, and the First Baron Avebury. He also was a good friend of Charles Darwin, whose hometown of Shrewsbury, Shropshire, I will be visiting in just under two weeks.  Last evening as I walked the dog after sunset, the sky still a fairly bright blue with plenty of light to see, I looked into the darkness of the woods behind our house and saw that the fireflies were beginning to flash their mating signals. I realized that I’m leaving Ohio at one of my favorite times of the year – firefly time! I love fireflies!

Last evening as I walked the dog after sunset, the sky still a fairly bright blue with plenty of light to see, I looked into the darkness of the woods behind our house and saw that the fireflies were beginning to flash their mating signals. I realized that I’m leaving Ohio at one of my favorite times of the year – firefly time! I love fireflies!