====================

A sermon offered on the Second Sunday of Easter, April 12, 2015, to the people of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Medina, Ohio, where Fr. Funston is rector.

(The lessons for the day are Acts 4:32-35; Psalm 133; 1 John 1:1-2:2; and John 20:19-31. These lessons can be read at The Lectionary Page.)

====================

I assume that you are all familiar with Leonardo da Vinci’s famous mural of The Last Supper in the refectory of the Convent of Santa Maria delle Grazie, Milan. Nearly all of us have seen reproductions of it; it is said to be one of the most reproduced (and most parodied or satirized) paintings in human history. I have been privileged to see it in person twice in my life: once when I was a 16-year-old student studying in Florence and again in the summer of 2000 when I chaperoned the Kansas City Youth Symphony on a concert tour of northern Italy.

Each time I have looked at that painting, either the original or reproductions, I have found myself drawn more to da Vinci’s depiction of the disciples than to his Jesus. We know from Leonardo’s notebooks who each of the figures is meant to be. Thomas, who figures prominently in today’s Gospel lesson, figures prominently in the painting, as well. He is the first figure on Jesus’ left, right next to Jesus, looking intently at Jesus (we see him only in profile) with his right index finger pointing in Jesus’ face!

Has anyone ever done that to you? Gotten in your face making a point, raising their finger in emphasis? [Gesturing with index finger pointed upward] You know that this is a serious person. They know the way the world is; they have a very definite view of reality; and they are intent and making sure you see and understand their viewpoint. In The Last Supper, Thomas is only the first person on Jesus’ left because he leaning over St. James the Greater to make his point. He is a serious person with a definite view of reality.

That’s why I never call St. Thomas “Doubting Thomas.” This was not, in the upper room, and never in any other Gospel story, a man filled with doubt. This man is serious, sure of himself, and sure of his world. He is, in a word, a realist, a pragmatist, not a doubter.

Although Thomas is listed among the Twelve in all of the Gospels, we only encounter him as a speaker in John’s Gospel, and our first view of him is in the discussion leading up to the raising of Lazarus. We are told that the disciples (perhaps it was even Thomas) tried to dissuade Jesus from returning to Bethany in Judea, where Lazarus and his sisters lived, because they believed his life would be in danger: they remind Jesus that the Judeans “were just now trying to stone you, and are you going there again?” (Jn 11:8) Jesus, however, will not be turned away, so Thomas says to his fellow disciples, “Let us also go, that we may die with him.” (Jn 11:16) This man is a serious realist.

He is so realistic, so down-to-earth, that he doesn’t understand metaphor. When, in his farewell discourse, Jesus says . . .

In my Father’s house there are many dwelling places. If it were not so, would I have told you that I go to prepare a place for you? And if I go and prepare a place for you, I will come again and will take you to myself, so that where I am, there you may be also. And you know the way to the place where I am going.

. . . Thomas’s very pragmatic reply is, “Lord, we do not know where you are going. How can we know the way?” (Jn 14:2-5)

So we should not be surprised, and we should not call Thomas a “doubter” when he demands proof of Jesus’ resurrection. Would any of us have been any different? And, let’s be honest, none of the other disciples were themselves any different. None of them believed it either. In his Gospel, Luke is very clear about that: “Mary Magdalene, Joanna, Mary the mother of James, and the other women with them who told . . . the apostles. But [their] words seemed to them an idle tale, and they did not believe them.” (Lk 24:10-11; emphasis added)

I’m fairly certain that when Thomas said, “Unless I see the mark of the nails in his hands, and put my finger in the mark of the nails and my hand in his side, I will not believe,” (Jn 20:25) he never really expected to have the chance. Such a thing simply wouldn’t fit into the real world he understood. He wasn’t a doubter; he was a realist.

So, I think, Thomas has gotten a bad rap because of this story and the story has gotten a resultingly bad interpretation. This is not a story about changing someone’s mind; it’s a story about changing someone’s life!

Confronted by the reality of the risen Jesus, Thomas the realist is confounded by what reality really is; his perception of reality and thus his life is what is changed. When Jesus rises to his challenge and invites him to “put your finger here and see my hands; reach out your hand and put it in my side,” (Jn 20:27) he is not belittling Thomas, but he is positing the possibility that Thomas’s reality was too little. Thomas’s vision of reality is too small, too limited; his life is too circumscribed. His worldview is defined too much by evidence and too little by trust. When Jesus calls him to believe, he is calling on him to accept the evidence of an intellectual proposition; he is inviting him to live into a whole new world of trust. This is not a story about changing someone’s mind; it’s a story about changing someone’s life!

In 1961, an English priest named J.B. Phillips published a short book entitled Your God Is Too Small. In it he challenged many prevailing notions of God, many of which we still have with us today. He called these the “unreal gods” and gave them names such as “the Resident Policeman,” the “Parental Hangover,” and the “Grand Old Man.” These unreal gods, he said, were the gods of what he called “the modern outlook, which regards the whole of life as a closed system.” That “modern outlook” is precisely the point of view that Thomas had before meeting the risen Jesus! It is a too-small vision of reality in which it is unthinkable that anything could happen outside of what Phillips called “the whole huge cause-and-effect process,” that view of the world supported by physical evidence of the sort Thomas initially wanted.

But Thomas’s life and point of view, and that of all the apostles, were radically altered by their experience of Christ’s resurrection. Phillips wrote:

We may . . . point out the great difference that has come to exist between the Christianity of the early days and that of today. To us it has become a performance, a keeping of rules, while to the men of those days it was, plainly, an invasion of their lives by a new quality of life altogether. The difference is due surely to the fact that we are so very slow (even though we realize our impotence) to discard the closed-system idea. *** With the closed-system sooner or later you have to say: “You can’t change human nature.” Ideals fail for very spiritual poverty, and cynicism and despair take their place. But the fact of Christ’s coming is itself a shattering denial of the closed-system idea which dominates our thinking. And what else is His continual advice to “have faith in God” but a call to refuse, despite all appearances, to be taken in by the closed-system type of thinking? “Ask and ye shall receive, seek and ye shall find, knock and it shall be opened unto you”—what are these famous words but an invitation to reach out for the Permanent and the [truly] Real? (Your God Is Too Small, online PDF, The Common Life, pp. 88-89)

The story of Thomas is a story for all of us because we too easily fall into that closed-system worldview with its rules and its limitations. The story of Thomas reminds us of a grander vision. A vision defined not by limitation but by possibility, governed not by scarcity but by abundance, ruled not by remembered offenses but set free by forgiveness and reconciliation.

This is the vision shared by “the men of those days” (as Phillips called them), the members of the earliest Christian community described by Luke in the Book of Acts, that community of believers “who . . . were of one heart and soul, and no one claimed private ownership of any possessions, but everything they owned was held in common.” They had this shared vision because “the apostles gave their testimony to the resurrection of the Lord Jesus.” In other words, Mary Magdalene and the other women told their story of the empty tomb and of meeting Jesus in the garden; Cleopas and his companion told their story of meeting Jesus along the road to Emmaus; Thomas and the others told their story of meeting Jesus in the upper room.

The result was that peoples’ lives were changed. They lived in a way radically different than they had before, radically different from those around them: “There was not a needy person among them, for as many as owned lands or houses sold them and brought the proceeds of what was sold. They laid it at the apostles’ feet, and it was distributed to each as any had need.”

“From each according to his ability; to each according to his need” is not an economic model developed by Karl Marx; it is a religious model lived by the followers of Jesus Christ whose lives have been radically altered by their encounter with the Risen Lord. “Oh, how good and pleasant it is, when brethren live together in unity!” (Ps 133:1)

We live in different times. The total sharing of resources practice by Christ’s first followers no longer seems practical to us. We say to ourselves, “It just won’t work in our circumstances.” And we call ourselves realists and pragmatists. We hang onto that closed-system model and say [gesturing with index finger pointed upward]: “You can’t change human nature.”

But Jesus appeared to Thomas and said, “Put your finger here and see my hands. Reach out your hand and put it in my side. Do not doubt but believe.” (Jn 20:27) And proved that he can change human nature. Are we willing to let him change ours?

====================

A request to my readers: I’m trying to build the readership of this blog and I’d very much appreciate your help in doing so. If you find something here that is of value, please share it with others. If you are on Facebook, “like” the posts on your page so others can see them. If you are following me on Twitter, please “retweet” the notices of these meditations. If you have a blog of your own, please include mine in your links (a favor I will gladly reciprocate). Many thanks!

====================

Father Funston is the rector of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Medina, Ohio.

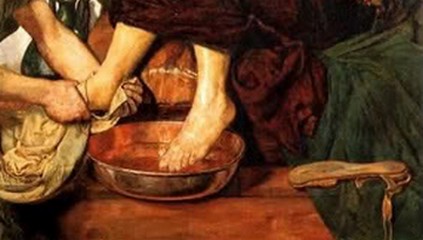

Every year on Maundy Thursday in the Episcopal Church we do this thing: we gather for Eucharist and we hear these lessons – the story of the Passover from the Book of Exodus, St. Paul’s retelling of the institution narrative of the Eucharist, and St. John’s story of the Last Supper in which he focuses not on the meal but on Jesus’ act of humility and service during the meal (probably quite early in the evening) of washing the feet of the others present.

Every year on Maundy Thursday in the Episcopal Church we do this thing: we gather for Eucharist and we hear these lessons – the story of the Passover from the Book of Exodus, St. Paul’s retelling of the institution narrative of the Eucharist, and St. John’s story of the Last Supper in which he focuses not on the meal but on Jesus’ act of humility and service during the meal (probably quite early in the evening) of washing the feet of the others present. I was an English and American literature major in college (well, I finished as an English literature major – I was a biology major, a sociology major, an anthropology major, a philosophy major, and an undeclared major before ending up with a degree in literature.) I remember a certain type of end-of-term take home exam, the compare-and-contrast question. For instance, you’d read a bunch of novels and then along would come the final exam with a question like, “Compare and contrast the vision of the sea in Hemingway’s

I was an English and American literature major in college (well, I finished as an English literature major – I was a biology major, a sociology major, an anthropology major, a philosophy major, and an undeclared major before ending up with a degree in literature.) I remember a certain type of end-of-term take home exam, the compare-and-contrast question. For instance, you’d read a bunch of novels and then along would come the final exam with a question like, “Compare and contrast the vision of the sea in Hemingway’s  After I did my first sermon-prep read through of this morning’s gospel I thought, “There are two stories here.” Then I thought, “No, there are three.” And then I realized that there are really more stories here than I can count.

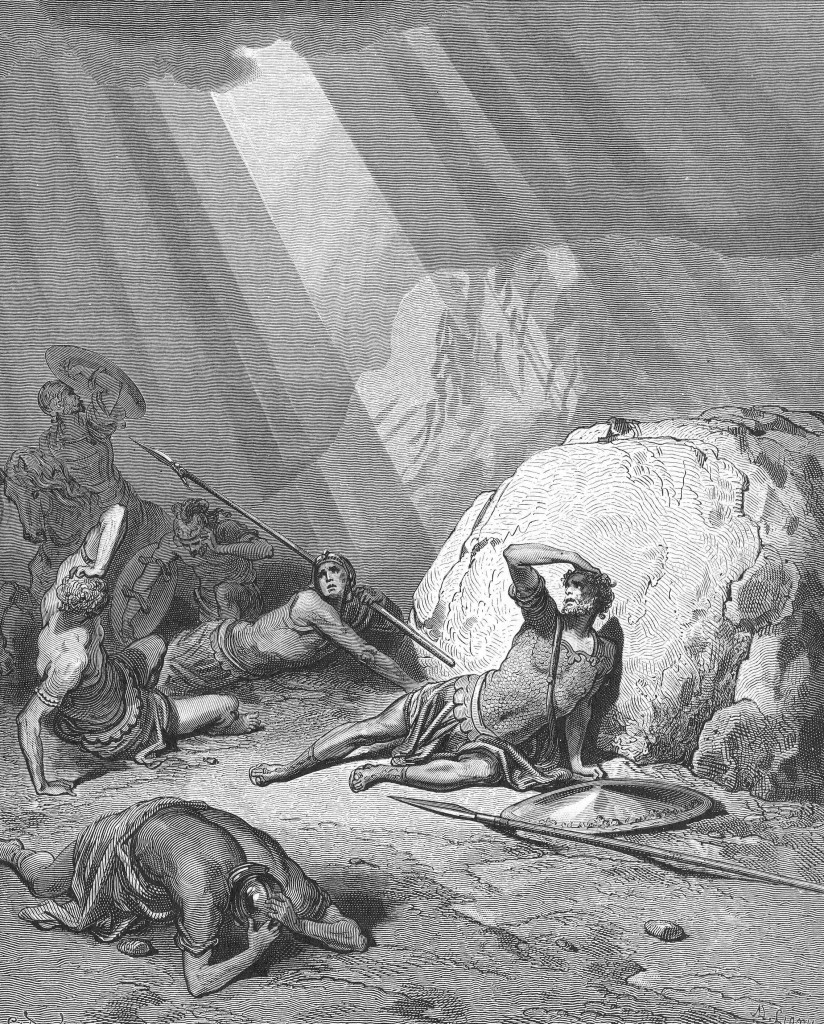

After I did my first sermon-prep read through of this morning’s gospel I thought, “There are two stories here.” Then I thought, “No, there are three.” And then I realized that there are really more stories here than I can count.  “I heard a voice saying in Hebrew: ‘I have a job for you. I’ve handpicked you to be a servant and witness to what’s happened today, and to what I am going to show you. I’m sending you off to open the eyes of the outsiders so they can see the difference between dark and light, and choose light, see the difference between Satan and God, and choose God.'” (Acts 26:16-18a, The Message)

“I heard a voice saying in Hebrew: ‘I have a job for you. I’ve handpicked you to be a servant and witness to what’s happened today, and to what I am going to show you. I’m sending you off to open the eyes of the outsiders so they can see the difference between dark and light, and choose light, see the difference between Satan and God, and choose God.'” (Acts 26:16-18a, The Message)  Tonight we gather once again to celebrate a memory, the memory of the birth of Christ, the Christ who is about to be born again as he is every year. We don’t really know if he was born at this time of the year; in fact, most scholars agree he wasn’t. But that doesn’t matter. It isn’t the date that we celebrate; it is his birth, then and in our lives each time we remember.

Tonight we gather once again to celebrate a memory, the memory of the birth of Christ, the Christ who is about to be born again as he is every year. We don’t really know if he was born at this time of the year; in fact, most scholars agree he wasn’t. But that doesn’t matter. It isn’t the date that we celebrate; it is his birth, then and in our lives each time we remember. I’m sitting in my office in the basement of the church building. So far as I know, I’m the only person here.

I’m sitting in my office in the basement of the church building. So far as I know, I’m the only person here.

Tonight, as my diocese begins its annual governing convention in traditional fashion with a celebration of the Holy Eucharist, we will doing so in the context of an ordination – two ordinations, in fact, one to the diaconate and one to the presbyterate. This morning’s reading from Ben Sira is lengthy description of the glories of the ceremonial priesthood. One might have expected the church to have made this one of the potential readings for a presbyteral ordination, but in its wisdom, it has not.

Tonight, as my diocese begins its annual governing convention in traditional fashion with a celebration of the Holy Eucharist, we will doing so in the context of an ordination – two ordinations, in fact, one to the diaconate and one to the presbyterate. This morning’s reading from Ben Sira is lengthy description of the glories of the ceremonial priesthood. One might have expected the church to have made this one of the potential readings for a presbyteral ordination, but in its wisdom, it has not.