====================

This sermon was preached on the Fifteenth Sunday after Pentecost, September 1, 2013, at St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Medina, Ohio, where Fr. Funston is rector.

(Revised Common Lectionary, Pentecost 15 (Proper 17, Year C): Jeremiah 2:4-13; Psalm 81:1,10-16; Hebrews 13:1-8,15-16; and Luke 14:1, 7-14. These lessons can be read at The Lectionary Page.)

====================

Finish this verse: “The Lord helps those . . . .”

Finish this verse: “The Lord helps those . . . .”

Congregation responds: “. . . . who help themselves.”

Do you know where to find that in Scripture?

You won’t. It’s not there. But a lot of people think it is. A survey done by the Barna organization within the past few years showed that at least 80% of American Christians believe that old saying is a biblical verse! It’s not.

“God helps those who help themselves” is probably the most often quoted piece of “Scripture” not found in the Bible. This saying is usually attributed to Ben Franklin because it was quoted in Poor Richard’s Almanac in 1757. In reality it predates Franklin by several centuries! One of the earliest forms of this saying goes back to Aesop’s fable, Hercules and the Waggoner, where the moral of the story is “the gods help them that help themselves.” The modern variant, “God helps those who help themselves,” was first coined by the English political theorist Algernon Sydney in a posthumous essay published in 1698 entitled Discourses Concerning Government. It is not a religious sentiment at all; it comes from moralistic politics! And it carries with it an implied negative corollary – that God will refuse to help those who (for whatever reason) don’t help themselves!

It also demands that we consider the truth of what happens to those who do help themselves . . . those who help themselves to too much . . . those who, as Jeremiah put it, “go after worthless things, and become worthless themselves.”

But for now let us consider, instead, the simple and straightforward statement we find in the Letter to the Hebrews: “The Lord is my helper; I will not be afraid. What can anyone do to me?” The writer of the Letter is quoting from Psalm 118. In the prayer book this declaration is phrased: “The Lord is at my side, therefore I will not fear; what can anyone do to me?” This is a theme we find again and again in the Psalms: the nearness and unconditional nature of God’s aid.

When my mother planned her funeral (something I encourage everyone to think about doing; it is a real gift to your survivors!) she chose Psalm 121 to be read; that psalm is also appointed for the Feast of St. Francis of Assisi, and so for two reasons it is one of my favorites. That psalm reads:

1 I lift up my eyes to the hills; *

from where is my help to come?

2 My help comes from the Lord, *

the maker of heaven and earth.

3 He will not let your foot be moved *

and he who watches over you will not fall asleep.

4 Behold, he who keeps watch over Israel *

shall neither slumber nor sleep;

5 The Lord himself watches over you; *

the Lord is your shade at your right hand,

6 So that the sun shall not strike you by day, *

nor the moon by night.

7 The Lord shall preserve you from all evil; *

it is he who shall keep you safe.

8 The Lord shall watch over your going out and your coming in, *

from this time forth for evermore.

The graphic on the front of our bulletin this morning is a quotation from the King James version of another psalm, Psalm 46. In the prayer book, the first few verse are rendered:

1 God is our refuge and strength, *

a very present help in trouble.

2 Therefore we will not fear, though the earth be moved, *

and though the mountains be toppled into the depths of the sea;

3 Though its waters rage and foam, *

and though the mountains tremble at its tumult.

4 The LORD of hosts is with us; *

the God of Jacob is our stronghold.

Psalm 46 was the inspiration for Martin Luther’s great hymn, a favorite of this congregation, A Mighty Fortress Is Our God.

Nowhere in these psalms, nor anywhere else in the Bible will you find anything that provides a Judaic or Christian basis for the sentiment that “God helps those who help themselves” and its negative corollary that God refuses to assist those who don’t. In fact, the Bible teaches the opposite. God helps the helpless, the poor, the weak, the needy! The Prophet Isaiah, for example, declares, “For you have been a refuge to the poor, a refuge to the needy in their distress, a shelter from the rainstorm and a shade from the heat. When the blast of the ruthless was like a winter rainstorm, the noise of aliens like heat in a dry place, you subdued the heat with the shade of clouds; the song of the ruthless was stilled.” (Isa. 25:4-5) In the Letter to the Romans, St. Paul declares, “For while we were still weak, at the right time Christ died for the ungodly.”

Jesus once told a parable that underscored the unconditional nature of God’s help:

Which one of you, having a hundred sheep and losing one of them, does not leave the ninety-nine in the wilderness and go after the one that is lost until he finds it? When he has found it, he lays it on his shoulders and rejoices. And when he comes home, he calls together his friends and neighbors, saying to them, “Rejoice with me, for I have found my sheep that was lost.” (Luke 15:4-6)

We human beings are the lost sheep of this parable, the completely helpless sheep, in need of God’s saving help.

God does not help those who can help themselves, simply because no one can do so! We cannot help ourselves; we cannot free ourselves from slavery to sin and death. Our own power fails us when we rely on it, rather than God.

As another psalm (Psalm 118) says:

16 There is no king that can be saved by a mighty army; *

a strong man is not delivered by his great strength.

17 The horse is a vain hope for deliverance; *

for all its strength it cannot save.

18 Behold, the eye of the Lord is upon those who fear him, *

on those who wait upon his love,

19 To pluck their lives from death, *

and to feed them in time of famine.

To believe that God’s help is conditioned on our helping ourselves is foolish. It is not only unbiblical, it is prideful! Pride and arrogance motivate us to believe that we can do everything through our own effort and with our own merit, that we can pick ourselves up by our own spiritual and moral bootstraps. However, the clear warrant of Scripture is that “God opposes the proud, but gives grace to the humble.” (James 4:6)

I got to thinking about the contrast between that popular aphorism and the teaching of Scripture because of the Gospel lesson. In the Gospel lesson for today in which Jesus gives the advice:

When you are invited [to a banquet], go and sit down at the lowest place, so that when your host comes, he may say to you, “Friend, move up higher”; then you will be honored in the presence of all who sit at the table with you. For all who exalt themselves will be humbled, and those who humble themselves will be exalted.

It occurred to me that Jesus is, indeed, addressing that second corollary of the old aphorism, that question I suggest at the beginning of this sermon: what happens to those who do help themselves . . . those who help themselves to too much? “All who exalt themselves will be humbled” is a pretty clear answer.

We live in a world dominated by those who have helped themselves to quite a bit. We live in a world where there are a few (“the 1%” we have come to call them), who have helped themselves to much, much more than they will ever be able to use, to the detriment of those who could make very good use of it. The writer of the Letter to the Hebrews clearly counseled against such acquisitiveness: “Keep your lives free from the love of money, and be content with what you have; for he has said, ‘I will never leave you or forsake you.’” And he said, “Do not neglect to do good and to share what you have, for such sacrifices are pleasing to God.”

Trust in God. Everything else will fade; everything else will let you down. Over and over again the Bible teaches this lesson that we humans have a hard time understanding. Our tendency is to put our trust in and help ourselves to things, money, stuff. Somebody once asked John Rockefeller how much was enough; he answered, “Just a little bit more.”

I hate to say it, but we are all like that. We accumulate stuff at an incredible rate. We can’t seem to let go of what we have and we are always gather just a little bit more. We build extra garages for our stuff. I read recently that there are now more than 35,000 self-help storage facilities in the United States, with something like 1-1/2 billion square feet of extra storage because our houses and apartments can’t contain it all. I confess – Evelyn and I rent one of those units: it’s full of stuff we haven’t visited in a couple of years. I don’t really know why we keep it! I guess because we’re just like other people. The more we have, the more we need; the more we have, the more we worry about it. We have become like those against whom Jeremiah prophesied, like those who “went after worthless things, and became worthless themselves.”

But, says the Letter to the Hebrews, “be content with what you have; for [God] has said, ‘I will never leave you or forsake you.’” And Jesus, continuing the imagery of the banquet, said to his host in today’s Gospel story (and to us):

When you give a luncheon or a dinner, do not invite your friends or your brothers or your relatives or rich neighbors, in case they may invite you in return, and you would be repaid. But when you give a banquet, invite the poor, the crippled, the lame, and the blind. And you will be blessed, because they cannot repay you, for you will be repaid at the resurrection of the righteous.

Give the stuff away. Give it to those who need it. Help yourself by divesting yourself of all that stuff.

If there is any truth in that old saying that “God helps those who help themselves” it is in this, that God will repay those who give their stuff to the poor, the crippled, the lame, and the blind; that God will help those who help others. God will help those who help themselves by getting rid of the accumulated possessions we have but do not need, the accumulated wealth that can be of use to others. We don’t need it! And we needn’t be afraid of losing it. “The Lord is my helper; I will not be afraid. What can anyone do to me?”

“Do not neglect to do good and to share what you have, for such sacrifices are pleasing to God.” Those with whom you share may not be able to repay you, but “you will be repaid at the resurrection of the righteous.”

So now, let’s finish that verse differently: “The Lord helps those . . . who help others!”

Amen.

====================

A request to my readers: I’m trying to build the readership of this blog and I’d very much appreciate your help in doing so. If you find something here that is of value, please share it with others. If you are on Facebook, “like” the posts on your page so others can see them. If you are following me on Twitter, please “retweet” the notices of these meditations. If you have a blog of your own, please include mine in your links (a favor I will gladly reciprocate). Many thanks!

====================

Father Funston is the rector of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Medina, Ohio.

My parish is currently undertaking a building renovation which will include redoing some of the concrete pathways and landscaping. In the process of overseeing this work, I’ve learned a new word – hardscape – which means the area of a designed landscape made up of hard wearing materials such as stone, concrete, and similar construction materials. I’ve been thinking about rocks and stones for the better part of a month. That’s why I haven’t written one of these meditations . . .

My parish is currently undertaking a building renovation which will include redoing some of the concrete pathways and landscaping. In the process of overseeing this work, I’ve learned a new word – hardscape – which means the area of a designed landscape made up of hard wearing materials such as stone, concrete, and similar construction materials. I’ve been thinking about rocks and stones for the better part of a month. That’s why I haven’t written one of these meditations . . .  We are used to thinking of the Book of Isaiah as the work of a single prophet, but it is really three books: First Isaiah, comprising chapters 1-39; Second Isaiah, made up of chapters 40-55; and Third Isaiah, chapters 56-66. These three prophets did their work in three different and distinct periods in Jewish history: the late 8th Century BCE; the mid-6th Century BCE, and the late 6th Century BCE, respectively. This is clear from evidence in their writings: their themes vary and each prophet speaks from a different location. First Isaiah is clearly set in pre-exilic Jerusalem; Second Isaiah was obviously written in Babylon; Third Isaiah speaks from post-exilic Jerusalem. Nonetheless, there is a sense of unity in the writings that make up this book. Phrases and themes recur, and there are linkages later and earlier passages. Today’s reading is from First Isaiah and introduces a topic which will be taken up again by Second and Third Isaiah: what constitutes proper worship?

We are used to thinking of the Book of Isaiah as the work of a single prophet, but it is really three books: First Isaiah, comprising chapters 1-39; Second Isaiah, made up of chapters 40-55; and Third Isaiah, chapters 56-66. These three prophets did their work in three different and distinct periods in Jewish history: the late 8th Century BCE; the mid-6th Century BCE, and the late 6th Century BCE, respectively. This is clear from evidence in their writings: their themes vary and each prophet speaks from a different location. First Isaiah is clearly set in pre-exilic Jerusalem; Second Isaiah was obviously written in Babylon; Third Isaiah speaks from post-exilic Jerusalem. Nonetheless, there is a sense of unity in the writings that make up this book. Phrases and themes recur, and there are linkages later and earlier passages. Today’s reading is from First Isaiah and introduces a topic which will be taken up again by Second and Third Isaiah: what constitutes proper worship? I am often complimented on my knowledge of biblical history, especially the lesser known stories of the Old Testament. Some members of my parish tell me how much they enjoy it when I make an exegetical digression in a sermon to explain the background of some bit of text. Yesterday, a retired clergy colleague extended the compliment to “your seminary professors,” who, he was sure, did a much better job of teaching the Scriptures than had his own mentors.

I am often complimented on my knowledge of biblical history, especially the lesser known stories of the Old Testament. Some members of my parish tell me how much they enjoy it when I make an exegetical digression in a sermon to explain the background of some bit of text. Yesterday, a retired clergy colleague extended the compliment to “your seminary professors,” who, he was sure, did a much better job of teaching the Scriptures than had his own mentors. In last week’s sermon I talked about the first three prophetic visions God reveals to Amos: a plague of locusts devouring the crops of ancient Israel, a catastrophic fire destroying everything in the nation, and the plumb line set in the midst of the nation’s people demonstrating that they were not upright. This week Amos is shown a fourth prophetic vision.

In last week’s sermon I talked about the first three prophetic visions God reveals to Amos: a plague of locusts devouring the crops of ancient Israel, a catastrophic fire destroying everything in the nation, and the plumb line set in the midst of the nation’s people demonstrating that they were not upright. This week Amos is shown a fourth prophetic vision.  Jesus had healed someone on the sabbath; that’s the simple back ground to the Pharisees and Herodians conspiracy against Jesus. This alliance is an interesting one since in generally the two groups hated one another! But their fear of Jesus apparently was enough to get them to work together against him.

Jesus had healed someone on the sabbath; that’s the simple back ground to the Pharisees and Herodians conspiracy against Jesus. This alliance is an interesting one since in generally the two groups hated one another! But their fear of Jesus apparently was enough to get them to work together against him. Occasionally when studying Scripture I have thought, “This can’t possibly have happened.” I’m sure that what I am reading is meant to be an allegory or a metaphor, or that it is simply pious legend that the biblical author has incorporated into his story. This strange little story of the death of Herod Agrippa I was one of those passages. It’s just a little weird.

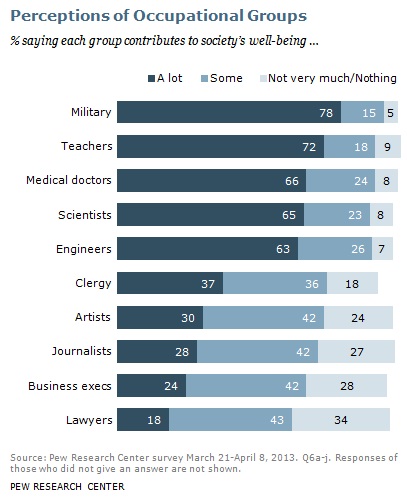

Occasionally when studying Scripture I have thought, “This can’t possibly have happened.” I’m sure that what I am reading is meant to be an allegory or a metaphor, or that it is simply pious legend that the biblical author has incorporated into his story. This strange little story of the death of Herod Agrippa I was one of those passages. It’s just a little weird.  Last week, The Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life published the results of

Last week, The Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life published the results of

The nation’s legal system is corrupt; justice is for sale to the highest bidder. The guilty go free while the innocent suffer and die. The rich are crushing the poor. The affluent, the 1%-ers, are living a lavish life, with their costly perfumes and cosmetics, and their vacation homes with expensive furnishings, pleasure palaces where they can throw extravagant parties with music in every room. They revel in sexual debauchery of all sorts, but try to enforce a puritanical moral code on the rest of society. The poor are at the mercy of predatory lenders who exploit vulnerable families. The rich have more than enough to eat and to waste, while the poorest in the society go hungry. And government and religious leaders not only allow this to happen, they help it happen.

The nation’s legal system is corrupt; justice is for sale to the highest bidder. The guilty go free while the innocent suffer and die. The rich are crushing the poor. The affluent, the 1%-ers, are living a lavish life, with their costly perfumes and cosmetics, and their vacation homes with expensive furnishings, pleasure palaces where they can throw extravagant parties with music in every room. They revel in sexual debauchery of all sorts, but try to enforce a puritanical moral code on the rest of society. The poor are at the mercy of predatory lenders who exploit vulnerable families. The rich have more than enough to eat and to waste, while the poorest in the society go hungry. And government and religious leaders not only allow this to happen, they help it happen.