====================

A sermon offered by the Rev. Dr. C. Eric Funston on Palm Sunday, March 20, 2016, to the people of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Medina, Ohio, where Fr. Funston is rector.

(The lessons for the day are as follows:

At the Blessing and Distribution of the Palms: Zechariah 9:9-12 and Psalm 118:1-2,19-29

At the Eucharist: Isaiah 50:4-9a; Philippians 2:5-11; Psalm 31:9-16; and St. Luke 19:28-40

At the Reading of the Passion Narrative following Communion: St. Luke 22:14-23:56

Most of these lessons may be found at The Lectionary Page.)

====================

What is Jesus up to? Why is he doing this?

What is Jesus up to? Why is he doing this?

Many of us are old enough to remember when the musicals Godspell and Jesus Christ Superstar made their first appearances. I wasn’t that big a fan of Godspell, but I really liked Superstar … and one of my favorite songs from it is Hosanna sung as Jesus enters Jerusalem, the scene which today specifically commemorates.

In Superstar, as in the Bible, as Jesus makes his way into the city, the crowds sing “Hosanna”. Unlike the biblical text, the hosannas sung in Superstar are a refrain for a duet, a musical conversation between Caiaphas, the high priest, and Jesus. In each iteration of the refrain, one line is changed. The first time, the crowd sings “Hey, JC, JC, won’t you smile at me.” The second time, “Hey JC, JC you’re alright by me.” The third, “Hey JC, JC won’t you fight for me?” And finally, “Hey JC, JC won’t you die for me?” These one-line changes in the hosanna refrain foreshadow the progress of Holy Week and the events leading to Good Friday and the cross. There’s a sermon in that, but not the one I want to offer you today.

Today, I want to focus not on what the crowd is singing but on what Jesus is saying by what he does and what he says. Listen to the words Caiaphas says to Jesus in the Superstar song:

Tell the rabble to be quiet,

we anticipate a riot.

This common crowd,

is much too loud.

Tell the mob who sing your song

that they are fools and they are wrong.

They are a curse.

They should disperse.

Tim Rice, the lyricist of Superstar, is elaborating here on the Lukan text: “Some of the Pharisees in the crowd said to him, ‘Teacher, order your disciples to stop.'” (Luke does not identify the speaker as the high priest Caiaphas; that is artistic license on the playwrights’ part.) Jesus’ reply, “I tell you, if these were silent, the stones would shout out,” is rendered by lyricist Rice in this way:

Why waste your breath moaning at the crowd?

Nothing can be done to stop the shouting.

If every tongue were stilled

The noise would still continue.

The rocks and stone themselves would start to sing.

This conversation gives us a clue as to Jesus’ intent, his motive for doing what he did on that day riding into Jerusalem.

Way back in Jewish history, Joshua the son of Nun, the successor of Moses, when he led the people of Israel into the promised land swore them to their covenant with God and he had his men set up a stone monument as a testimony to the covenant. He said to the people, “See, this stone shall be a witness against us; for it has heard all the words of the Lord that he spoke to us; therefore it shall be a witness against you, if you deal falsely with your God.” (Josh. 24:27) Later, the prophet Habakkuk condemned the ruling classes, the conquerors of nations who, in his colorful and disturbing words, “build towns by bloodshed.” (Hab 2:12) In his prophecy, Habakkuk proclaimed: “The very stones will cry out from the wall, and the plaster will respond from the woodwork.” (Hab 2:13)

Jesus was recalling these ancient words, the covenant promise of Joshua and the justice prophecy of Habakkuk, when he said to the complaining Pharisees, “The stones would shout out.” They claimed to be the guardians of the covenant and they were the ruling class of their day, trained in the Law of Moses and the history of their people, and they knew what Jesus was saying.

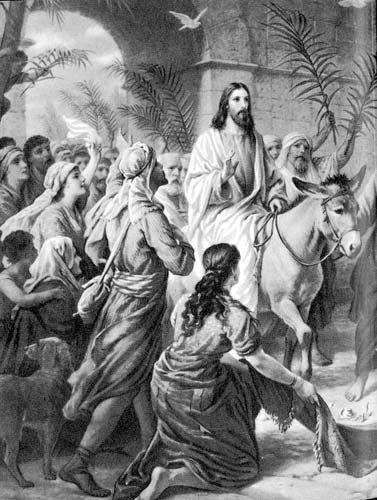

They knew, too, what Jesus had done riding into the city on a donkey’s colt. He was acting out the prophecy of Zechariah: “Lo, your king comes to you; triumphant and victorious is he, humble and riding on a donkey, on a colt, the foal of a donkey.” Jesus was making a bold statement of his identity, a claim that could not be ignored. He was staking his claim on the kingship of Israel, on the role of the one who sits in judgment of the injustice against which the stones cry out and the plaster on the walls responds. He was telling them in no uncertain terms that they, the ruling class of his day, had built their empire by bloodshed.

That is what Jesus was up to then . . . and it is what Jesus is up to now! When the church re-enacts this drama each year, when we read the story of Jesus’ entry into Jerusalem, when we wave our palms and sing our hosannas, we who “are the body of Christ and individually members of it” are making the same prophetic claim. We are saying to the ruling elites of our day that the rules by which they profit and benefit are unjust, that the society over which they preside is an empire built by bloodshed, that the stones are crying out from the wall, and the plaster is responding from the woodwork, that God’s creation is bearing witness against them.

And in one of those twists of meaning that God frequently pulls on us, we recognize that even as we “are the body of Christ and individually members of it,” even as we are both Jesus riding into Jerusalem and the crowds, the stones, crying out for justice . . . we are also the ruling elites against whom we cry. It is our own unjust acts, our own oppression of others, our own sinful exploitations that we are prophetically protesting.

If we do not understand that, if we do not appreciate that that is what we are saying and doing, then our Palm Sunday liturgy is hollow and meaningless. If what we are doing is not a reiteration of Jesus’ message, not a repetition of the prophecy he enacted and proclaimed, then what we are doing is a mockery of his life, his ministry, and his self-sacrifice. If in our waving of palms and singing of hosannas we are not proclaiming his gospel, if we are not announcing “good news to the poor . . . release to the captives . . . recovery of sight to the blind [and freedom to] the oppressed” (Lk 4:18), then all that we do today and during this Holy Week is nothing more than a burlesque, a charade, “a tale told by an idiot, full of sound and fury, signifying nothing.” (Macbeth, Act V, Scene V)

But . . . but . . . I do not believe that it is. I believe that what we do bears witness to the truth of the gospel story, that what we do makes a difference in the world in which we live. I believe that what we do proclaims to the powers of this world the almighty power of the God and Father of our Lord Jesus Christ. I believe that when we wave our palms and sing our hosannas we are, like the prophet Isaiah, standing up and saying, “Who will contend with [us]? Let us stand up together. Who are [our] adversaries? Let them confront [us]. It is the Lord God who helps [us]; who will declare [us] guilty?” (Is 50:9)

We are proclaiming to the powers of this world, even (or even especially) those that reside within us, that they are defeated, that “in Christ, there is a new creation: everything old has passed away; see, everything has become new!” (2 Cor 5:17) We are saying, “Our God reigns!” and that “in Christ God [has] reconcile[ed] the world to himself.” (2 Cor. 5:18)

That’s what Jesus is up to! That’s what we are up to!

At the end of the Hosanna! song in Jesus Christ Superstar, Jesus sings to the crowd:

Sing me your songs,

But not for me alone.

Sing out for yourselves,

For you are bless-ed.

There is not one of you

Who cannot win the kingdom.

The slow, the suffering,

The quick, the dead.

So wave your palms! Sing your hosannas! Be the stones who cry out judgment against the ruling elites! Be the plaster that answers from the woodwork! Be ambassadors for Christ! Be the voices of God’s ministry of reconciliation! Be the righteousness of God! (2 Cor 5) For there is not one of you who cannot win the kingdom! Amen!

====================

A request to my readers: I’m trying to build the readership of this blog and I’d very much appreciate your help in doing so. If you find something here that is of value, please share it with others. If you are on Facebook, “like” the posts on your page so others can see them. If you are following me on Twitter, please “retweet” the notices of these meditations. If you have a blog of your own, please include mine in your links (a favor I will gladly reciprocate). Many thanks!

====================

Father Funston is the rector of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Medina, Ohio.

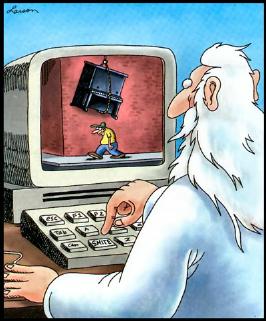

Some years ago the cartoonist Gary Larson published a cartoon of an old white-bearded judgmental God sitting at his computer terminal watching the live-streaming video of some feckless and unsuspecting sinner walk under a piano suspended from a crane while God’s finger is poised over a button on the keyboard labeled “Smite”. This seems to be the God these folk are describing to Jesus, a bookkeeper god who keeps a running tally of the good things and bad things we may do and then at some arbitrary point pushes the “Smite” button and puts paid to our cosmic account. This is the god of those who ask “Why me? What have I done to deserve this?” when something bad happens to them. This is the god of those who say “Everything happens for a reason” when something bad happens to someone else. This is the picture of God that Jesus rejects utterly and completely.

Some years ago the cartoonist Gary Larson published a cartoon of an old white-bearded judgmental God sitting at his computer terminal watching the live-streaming video of some feckless and unsuspecting sinner walk under a piano suspended from a crane while God’s finger is poised over a button on the keyboard labeled “Smite”. This seems to be the God these folk are describing to Jesus, a bookkeeper god who keeps a running tally of the good things and bad things we may do and then at some arbitrary point pushes the “Smite” button and puts paid to our cosmic account. This is the god of those who ask “Why me? What have I done to deserve this?” when something bad happens to them. This is the god of those who say “Everything happens for a reason” when something bad happens to someone else. This is the picture of God that Jesus rejects utterly and completely.

As many of you know, Evie and I were privileged to make a pilgrimage to the holy places of Palestine summer before last and one of the sites we visited was Mt. Tabor, the traditional “Holy Mountain” on which the Transfiguration is believed to have taken place.

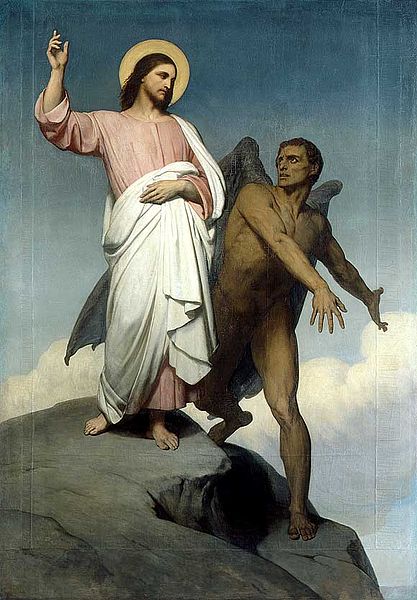

As many of you know, Evie and I were privileged to make a pilgrimage to the holy places of Palestine summer before last and one of the sites we visited was Mt. Tabor, the traditional “Holy Mountain” on which the Transfiguration is believed to have taken place. We’ve heard this Gospel story before. We all know what happens (at least in the Synoptic Gospels) after Jesus is baptized: a voice is heard from heaven, “You are my Son, the Beloved; with you I am well pleased” (Lk 3:22) and then Jesus goes into the desert for forty days of retreat where he grapples with temptations.

We’ve heard this Gospel story before. We all know what happens (at least in the Synoptic Gospels) after Jesus is baptized: a voice is heard from heaven, “You are my Son, the Beloved; with you I am well pleased” (Lk 3:22) and then Jesus goes into the desert for forty days of retreat where he grapples with temptations.

Languages and the study of languages fascinate me – if you didn’t know that before this series on the Lord’s Prayer, you probably know it now – and I am therefore always keenly aware of the difficulty of fully appreciating the Holy Scripture if we only consider the meaning of the English translation.

Languages and the study of languages fascinate me – if you didn’t know that before this series on the Lord’s Prayer, you probably know it now – and I am therefore always keenly aware of the difficulty of fully appreciating the Holy Scripture if we only consider the meaning of the English translation.  A Native American proverb instructs us, “When you were born, you cried and the world rejoiced; live your life in a manner that when you die, the world cries and you rejoice.” Today, on what would have been Sheryl Ann King’s 48th birthday, the world (you and me and everyone who knew and loved Sherry) is crying, but Sherry is rejoicing. “If you loved me,” Jesus told his followers, “you would rejoice that I am going to the Father” (Jn 14:28); we who love Sherry, let us rejoice (even through our tears) that she, too, has gone to the Father.

A Native American proverb instructs us, “When you were born, you cried and the world rejoiced; live your life in a manner that when you die, the world cries and you rejoice.” Today, on what would have been Sheryl Ann King’s 48th birthday, the world (you and me and everyone who knew and loved Sherry) is crying, but Sherry is rejoicing. “If you loved me,” Jesus told his followers, “you would rejoice that I am going to the Father” (Jn 14:28); we who love Sherry, let us rejoice (even through our tears) that she, too, has gone to the Father.