====================

This sermon was preached on October 16, 2013, at St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Manhattan, Kansas, where Fr. Funston’s son, the Rev. A. Patrick K. Funston is rector. Fr. Patrick was installed as rector, and the appointment of the Rev. Sandra Horton-Smith as Deacon in the parish was also celebrated.

(The Episcopal Church sanctoral lectionary for the Feast of Hugh Latimer & Nicholas Ridley, bishops and martyrs: Zephaniah 3:1-5; Psalm 142; 1 Corinthians 3:9-14; and John 15:20-16:1.)

====================

I bring you greetings from the people of St. Paul’s Parish, Medina, Ohio, where I am privileged to serve as rector. Nearly all the active members of our congregation know and respect Patrick, and have asked me to convey their congratulations to him and to you, together with the assurance of their prayers, as you continue together in a new ministry only recently begun. Of course, none of them know Sandy, but we offer our greetings and prayers for her diaconal ministry among you, as well.

I bring you greetings from the people of St. Paul’s Parish, Medina, Ohio, where I am privileged to serve as rector. Nearly all the active members of our congregation know and respect Patrick, and have asked me to convey their congratulations to him and to you, together with the assurance of their prayers, as you continue together in a new ministry only recently begun. Of course, none of them know Sandy, but we offer our greetings and prayers for her diaconal ministry among you, as well.

I suppose my son asked me to preach this evening because he believes that in 40 years of church leadership including 23 years in ordained ministry as a deacon, curate, associate rector, and now rector in four dioceses, I may have picked up one or two bits of useful information to pass along. I shall strive, Fr. Funston, to make it so.

Sandy, I have never been a vocational deacon and I have had only a little experience working with deacons in the course of my ministry; nonetheless, it is my hope there may be something in what I have to say that will be of use to you.

We are gathered this evening on the feast of two Anglican martyrs — Nicholas Ridley and Hugh Latimer. They were bishops of the reformed Church of England put to death, by being burned at the stake, during the short reign and attempted Roman Catholic restoration of Queen Mary I, eldest daughter of Henry VIII. During her less-than-six years on the English throne, nearly 300 Protestants were killed, including these two bishops, so she is known to history as “Bloody Mary.”

The bishops’ martyrdom is most notable for the probably apocryphal story that Latimer, as the fires were lighted beneath them, reached to Ridley, took him by the hand and said, “Be of good cheer, Master Ridley, and play the man, for we shall this day light such a candle in England as I trust by God’s grace shall never be put out.”

I’ll skip the other details of Latimer’s and Ridley’s lives and ministries; I bring them up really only to explain the otherwise incomprehensible choices of lessons for this service; one really must stretch to find anything remotely enlightening about parish ministry in Zephaniah’s “soiled, defiled, oppressing city” filled with faithless people and profane priests, or in the Psalmist’s languishing spirit and loud supplications. There may be (indeed there will be) times when both priest and people may feel like the Psalmist in the course of a pastorate (as Paul wrote to the Corinthians, the work of ministry will be tested by fire), but dwelling on that hardly seems a constructive way to begin the relationship.

I must admit that I was tempted to use the bishop’s martyrdom as a metaphor for parish ministry, but thought better of it; it would be an incomplete metaphor, at best. I think I’ve found a much better metaphor, but before I get to it, I want to digress for a moment and tell you something about our experience, my wife’s and mine, in raising our son.

When Patrick was in junior high school and high school, his band and orchestra directors said to us, “Your son is a talented musician. He could have a great career in music.”

“Yes!” we replied, “Encourage him in that!”

When he was in high school and college, his mathematics instructors said to us, “Your son is a natural mathematician. He could have a great career as a professor or a theoretician.”

“Yes!” we replied, “Encourage him in that!”

When he decided to major in business, we heard from his fellow students and his professors that he had a great mind for economics and finances, and could make millions as a financial planner.

“Yes!” we said, “Encourage that!”

Earlier in his life, from about the age of 14 on, when he was active as an acolyte, and in youth group, and in the diocesan peer ministry program, people would come to us and say, “Patrick has all the skills and the personality to be a wonderful priest.”

“No!” we cried, “Please do not encourage him that way!”

It’s not that we didn’t want Patrick to become a priest; we’re delighted that he has found his calling amongst the clergy of the church and that he has been called to be Rector in this parish. However, his becoming a priest or Sandy’s becoming a deacon is not something we, any of us, including them, have any business “wanting.” It isn’t something that we or anyone should be “encouraging.” Ordained ministry is something to be discerned and what it is to be discerned is whether the potential priest or deacon can be anything else.

Every potential clergy person is asked, over and over again, “Why do you want to be clergy?” And every priest and deacon here tonight has answered that question. We may have phrased the answer differently, but for each of us it is the same. It’s not that the person called to the diaconate wants to be a deacon; it’s that she must be a deacon! It’s not that the person called to priesthood wants to be a priest; it’s that he must be a priest!

Presbyterian pastor and author Frederick Buechner spoke for us all when he answered the question in his book, The Alphabet of Grace:

“I hear you are entering the ministry,” the woman said down the long table meaning no real harm. “Was it your own idea or were you poorly advised?” And the answer that she could not have heard even if I had given it was that it was not an idea at all, neither my own nor anyone else’s. It was a lump in the throat. It was an itching in the feet. It was a stirring of the blood at the sound of rain. It was a sickening of the heart at the sight of misery. It was a clamoring of ghosts. It was a name which, when I wrote it out in a dream, I knew was a name worth dying for even if I was not brave enough to do the dying myself and if I could not even name the name for sure. Come unto me all ye who labor and are heavy laden and I will give you a high and driving peace. I will condemn you to death. (Frederick Buechner, The Alphabet of Grace, pp. 109-110)

Buechner’s last sentence does call to mind the martyrdom of Latimer and Ridley and so many others: “I will condemn you to death.” As a description of the call to parish ministry it is both terrifying and terrific!

The Christ we follow, the Christ we proclaim, the Christ who said, “If they persecuted me, they will persecute you,” does call us, does lead us to die! To die to selfishness, to die to ego. But through that death he leads us to life. We die to self to uncover what the Quakers call, “that of God within” or the “inner Teacher” … the True Self. Your call, Patrick, to priesthood and yours, Sandy, to the diaconate … our call to parish ministry is a call to continue dying to self and, as a result, to continue becoming truly alive.

It is, as any priest or deacon here will tell you, a painful process. To be clergy in Christ’s church is, as Paul made quite clear in his letters to the congregations in Ephesus and Rome, a gift; it is a wonderful, precious, costly, and painful gift. It will take you into the deepest intimacy with God’s people, with your people. At times you will be with them in the midst of their worst nightmares – death and divorce, devastating illness and the depths of despair. At times, you will feel put-upon and misused. At times, you will feel left out and neglected. At times, there will be conflict, and it will seem like it is consuming you alive. At times, it may seem that, a bit like Latimer and Ridley, you are being burned at the stake, because people will hurt you, sometimes intentionally and spitefully, sometimes negligently, often simply because they are in pain.

But as I said a moment ago, that would be an incomplete metaphor because the source of that pain is also the source of the most exquisite joy, when that same intimacy will privilege you with sharing God’s people’s, your people’s happiest and most blessed moments – when two people commit themselves to one another for life, when their children are born, when they get that long-sought promotion, when their kids graduate with honors, when children marry, when grandchildren are born, when these people among whom and with whom you minister know themselves to be God’s beloved.

Cherish those intimate moments — both the painful and the joyful — because they are moments of grace. Each of them is unique; never fall into the black hole of thinking you’ve “been there, done that.” There may have been similar moments . . . but that couple has never been married before and never will be again, that baby has never been born or baptized before and never will be again, that teenager has never graduated from high school before and never will again, that man has never died before and never will again. Each intimate moment, painful or joyful, is unique and no one has ever been there before. Each unique intimate moment, painful or joyful, is bursting with the promise and potential of God’s grace!

Do not fear those moments of graceful intimacy; cherish them because it is in them that you and the people of St. Paul’s Parish will die to self and become truly alive, to continue growing in boldness and righteousness, in faithfulness and patience, in wisdom and even holiness. It is in those moments when we are in the presence of God, when we stand before the throne of grace.

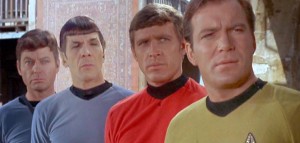

I think you know, Patrick, that one of my favorite verses of Scripture is from the Letter to Hebrews: “Let us therefore come boldly unto the throne of grace, that we may obtain mercy, and find grace to help in time of need.” (Heb. 4:16 KJV) So . . . if I say to you that our mission in parish ministry is to boldly go into those unique moments of grace where no one has gone before, you probably know that my metaphor for parish ministry is “the voyages of the Starship Enterprise.”

I read somewhere recently that one can consider oneself an unqualified success as a parent if you have raised your child to be a Star Trek fan; by that measure, Patrick’s mother and I were successful.

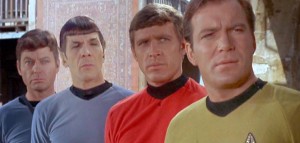

In the original Star Trek series, the crew’s uniforms were color coded: gold uniforms were command; red uniforms were engineering and security; and blue uniforms were science and medical. Parish ministry entails all three. So, Patrick, I have a little gift for you — a set of three pairs of official Star Trek color-coded uniform socks to remind you of these aspects of pastoral ministry.

In the original Star Trek series, the crew’s uniforms were color coded: gold uniforms were command; red uniforms were engineering and security; and blue uniforms were science and medical. Parish ministry entails all three. So, Patrick, I have a little gift for you — a set of three pairs of official Star Trek color-coded uniform socks to remind you of these aspects of pastoral ministry.

Gold — command: Patrick, the canons of your diocese (with which, you may recall, I have some familiarity) provide that as rector, “by virtue of such office, [you have] the powers and duties conferred by the General Canons of the Church, and in this connection shall exercise pastoral oversight of all guilds and societies within the parish, and [you are] entitled to speak and vote on all questions before these bodies.” (Canon IV.6, Diocese of Kansas) The canons provide that you are the chair person of the vestry and that you not only chair the annual meeting of the parish, you are also the final arbiter of who may vote at the meeting.

That’s a good deal of command authority and it should not be taken lightly. Remember two things about it. First, that you share it with others. The canons specify that the vestry “shall share with the Rector a concern and responsibility for the mission, ministry, and spiritual life of the parish.” (Canon IV.5.6(a)) But not only the vestry, all the good people this parish are your co-workers. As our catechism makes clear, “the ministers of the Church are lay persons, bishops, priests, and deacons;” every single baptized person, every member of this church has a ministry. The Rector does not do it alone, nor should he.

You remember on Star Trek: TOS, Captain Kirk went on every away mission. That’s a model of poor leadership; the captain should not have commanded, or even been a part of, every away team. Trust the rest of the crew — the vestry, the staff, volunteers, all the people of the parish — to handle things.

Remember Paul’s opening words to the Corinthians in this evening’s epistle: “We are God’s servants, working together . . . .” You and the vestry and people of this congregation are God’s servants, working together. You as the Rector don’t have to do it all — you do have to know what is happening; you have to be in the information loop and be privy to all the information pertinent to the running of the church and to ministering with and among its members, but you don’t have do it all!

I suspect that if Jesus were to critique Kirk’s style of leadership, he might say something along the lines of “It will not be so among you; whoever wishes to be great among you must be your servant.” (Matt. 20:26) That is the second thing to remember about command authority in the church. Be like the 6th Century pope St. Gregory the Great and remember that as a leader in the church you are the “servant of the servants of God.”

The red uniforms were for those doing engineering and security, and there is a lot of that in parish ministry. Much of it, knowing where the boilers are and how they work, knowing where the circuit breakers and fuses are, knowing how to fix a leaky faucet or a squeaky hinge or a broken kneeler . . . much of it falls into the category of “things they didn’t teach us in seminary.” But there is also a lot of engineering and security that they did teach us.

The ministry of word and sacrament are the engineering and security jobs of the parish priest; preaching God’s word and celebrating God’s Sacraments, for which seminary did prepare us. They are central to any priest’s ministry, and to do them well takes time and it takes prayer.

Preparing a sermon can easily consume 10-15 hours per week. Similarly, planning liturgies, not only for regular Sunday services, but for weddings, funerals, holidays, and other special events takes time and care. Many people are willing to say their clergy should put in this kind of time, but the only way the rector can have this time is if other demands are otherwise taken care of. I have admonished Patrick not to be Captain Kirk going on every away mission. So I admonish you, the people of St. Paul’s Parish, that you must not expect him to make every pastoral visit, oversee every parish activity, make every administrative decision. As St. Paul wrote the Ephesians, each member of the church is given grace according to the measure of Christ’s gift and each member must work to properly promoting the body’s growth. I encourage you to claim the shared ministry of the whole people of God and join with your rector and your deacons in providing pastoral care to one another, in managing parish activities, and in administrative governance.

Patrick, this obligation of the congregation means that you must answer it with a similar commitment. Just like Engineer Scott was always adjusting the “warp coils” and tuning the “dilithium crystals” (whatever those were), you must take time in prayer adjusting your spirit and tuning your psyche. Take the time your congregation gives you to prepare prayerfully for these “red uniform” ministries — preaching and sacramental celebration. Be like Captain Jean-Luc Picard in TNG; take private time in your “ready room;” spend time in conversation with God every day. Other things can wait or someone else can do them . . . but no one else can listen to God for you. You must spend your own time in prayer.

Sandy, I would say the same thing to you. Your engineering and security ministry will be different from Patrick’s, obviously. As a deacon, you are (I’m sure) familiar with the description of the role of the deacon as bringing the world’s needs to the attention of the church and taking the church’s ministry into service in the world. Deacons exemplify Christian discipleship, nurture others in their relationship to God, and lead church people to respond to the needs of the most needy, neglected, and marginalized of the world. Those are definitely “red uniform” tasks, and they too can only be done well with careful and prayerful preparation.

Prayer is also the “red uniform” ministry of whole congregation. The early 19th Century American Presbyterian preacher and seminary professor Gardiner Spring wrote in his book The Power of the Pulpit:

[H]ow unspeakably precious the thought to all who labor in this great work, whether in youthful, or riper years, that they are … habitually remembered in the prayers of the churches! Let the thought sink deep into the heart of every church, that their minister will be very much such a minister as their prayers may make him. If nothing short of Omnipotent grace can make a Christian, nothing less than this can make a faithful and successful minister of the Gospel!

We might express this thought differently today, but Gardiner’s point remains valid. Your prayers, good people, even more than their own, are the wellspring from which flows the water of God’s grace on which Patrick’s ministry as priest and Sandy’s as a deacon so much depend. If you wish their ministries to bear good fruit, do not forget to pray for them, and let them know that you are doing so!

Which brings us, at last, to the blue uniforms, the science and medical corps of the star ship. Mr. Spock the Science officer and Doctor “Bones” McCoy always wore blue. One of the ancient terms that we still use for pastoral ministry is “the cure of souls,” the word “cure” having pretty much the same meaning as it has in medicine. Broadly speaking, this ministry is the care, protection, and oversight of the nourishment and spiritual well-being of the souls committed to the pastor’s care; it may be shared with others, with deacons or with lay ministers, but it is truly the ministry of the parish priest. It is in this “blue shirt” ministry that those wonderful, painful, joyful, intimate moments of grace that I spoke of earlier will happen.

Which brings us, at last, to the blue uniforms, the science and medical corps of the star ship. Mr. Spock the Science officer and Doctor “Bones” McCoy always wore blue. One of the ancient terms that we still use for pastoral ministry is “the cure of souls,” the word “cure” having pretty much the same meaning as it has in medicine. Broadly speaking, this ministry is the care, protection, and oversight of the nourishment and spiritual well-being of the souls committed to the pastor’s care; it may be shared with others, with deacons or with lay ministers, but it is truly the ministry of the parish priest. It is in this “blue shirt” ministry that those wonderful, painful, joyful, intimate moments of grace that I spoke of earlier will happen.

It is customary at these services to ask the clergy about to be installed to stand for an admonition or a charge, but I’m not going to do that this evening. We aren’t here celebrating only the installation of the rector, or only the new ministry of these two clergy; we are celebrating the whole ministry of all the People of God in this parish. So I have a charge for all of you.

I know you expect me to say something like “explore strange new worlds, seek out new life and new civilizations, and boldly go where no one has gone before,” but that would just be too hokey, don’t you think?

No, I have rather more practical and down-to-earth advice.

Give each other time; give one another your attention; support one another with your prayers; respect yourselves and each other; and, most importantly, love one another. (Members of St. Paul’s, I can’t underscore the last one enough. You expect your clergy to remember your birthdays and your wedding anniversaries, to thank you when you perform some volunteer service, to greet you pleasantly when they see you at the grocery store. That’s only natural, and it’s right and proper that you do so. But, please, do the same for them! It is the most important thing the people of a parish can do for their clergy. Love Patrick and Sandy, their spouses and their families. Invite them into your homes. Remember their birthdays and anniversaries. Remember to say, “Thank you” once in a while. Believe me: it really is such little things that make all the difference.)

And, again, remember Paul’s words to the Corinthians: “We are God’s servants, working together.” So together represent Christ, bear witness to him wherever you may be and, according to the gifts given to each of you, carry on his work of reconciliation in the world.

If you do these things, you shall, by God’s grace, like Ridley and Latimer, light such a candle in Kansas, as, I trust, will never be put out.

Make it so! Amen!

====================

A request to my readers: I’m trying to build the readership of this blog and I’d very much appreciate your help in doing so. If you find something here that is of value, please share it with others. If you are on Facebook, “like” the posts on your page so others can see them. If you are following me on Twitter, please “retweet” the notices of these meditations. If you have a blog of your own, please include mine in your links (a favor I will gladly reciprocate). Many thanks!

====================

Father Funston is the rector of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Medina, Ohio.

I am later than usual committing to “paper” my thoughts on a portion of today’s readings, but these first verses of the lesson from Proverbs have been with me all day. Today is Shrove Tuesday, the day before the season of Lent begins, a day on which in the 2,000-year tradition of the church the faithful are encouraged to meet with a priest and make their confessions. The name, “Shrove Tuesday,” comes from the old English verb “to shrive,” which means to absolve of sin.

I am later than usual committing to “paper” my thoughts on a portion of today’s readings, but these first verses of the lesson from Proverbs have been with me all day. Today is Shrove Tuesday, the day before the season of Lent begins, a day on which in the 2,000-year tradition of the church the faithful are encouraged to meet with a priest and make their confessions. The name, “Shrove Tuesday,” comes from the old English verb “to shrive,” which means to absolve of sin.

The musical Godspell debuted in 1971 (my junior year in college); in it, Christ is portrayed as a clown. Whether it was an expression of or the catalyst for the phenomenon of offering clown eucharists as an edgy, avant-garde presentation of the Christian Mysteries, I really don’t know. The two are inextricably linked in my memory.

The musical Godspell debuted in 1971 (my junior year in college); in it, Christ is portrayed as a clown. Whether it was an expression of or the catalyst for the phenomenon of offering clown eucharists as an edgy, avant-garde presentation of the Christian Mysteries, I really don’t know. The two are inextricably linked in my memory. I have a pair of cufflinks with part of this verse inscribed on them in Latin: “Sacerdos in Aeternum” (“Priest Forever”). They were given to me as an ordination present. I seldom have reason or opportunity to wear them as I don’t generally wear long-sleeved, let alone French-cuff, shirts. But yesterday I did.

I have a pair of cufflinks with part of this verse inscribed on them in Latin: “Sacerdos in Aeternum” (“Priest Forever”). They were given to me as an ordination present. I seldom have reason or opportunity to wear them as I don’t generally wear long-sleeved, let alone French-cuff, shirts. But yesterday I did. “You shall draw water with rejoicing from the springs of salvation.”

“You shall draw water with rejoicing from the springs of salvation.” Today is the first Sunday in November which means that instead of the normal sequence of lessons for Ordinary Time, we are given the option of reading the lessons for All Saints Day, which falls every year on November 1. So today we heard a very strange reading from the Book of Daniel, a to-my-ear very troubling gradual psalm (in which we sing of wreaking vengeance on the nations and punishment on the peoples, of binding king in chains, and of inflicting judgment on the nobles bound in iron), a bit of Paul’s letter to the Church in Ephesus extolling the riches of the inheritance of the saints, and to Luke’s version of the Beatitudes in which Jesus not only blesses the poor, the hungry, and the weeping, he sighs woefully over the future plight people like ourselves – the comparatively wealthy, those whose bellies are full, and those in relatively good state of mind.

Today is the first Sunday in November which means that instead of the normal sequence of lessons for Ordinary Time, we are given the option of reading the lessons for All Saints Day, which falls every year on November 1. So today we heard a very strange reading from the Book of Daniel, a to-my-ear very troubling gradual psalm (in which we sing of wreaking vengeance on the nations and punishment on the peoples, of binding king in chains, and of inflicting judgment on the nobles bound in iron), a bit of Paul’s letter to the Church in Ephesus extolling the riches of the inheritance of the saints, and to Luke’s version of the Beatitudes in which Jesus not only blesses the poor, the hungry, and the weeping, he sighs woefully over the future plight people like ourselves – the comparatively wealthy, those whose bellies are full, and those in relatively good state of mind. The saints whom we celebrate on this day (and the many who are given special days of individual recognition) were people who tried to live according to the Bible as they understood its teachings. Like us, they read it and encountered those troubling visions, those petulant patriarchs, those bloodthirsty psalms, and somehow looked past them and through them to see the God of faith, the God who Incarnate in Jesus said, “Love your enemies, do good to those who hate you, bless those who curse you, pray for those who abuse you.” We extoll the virtues of those saint and we celebrate their lives and their witness because they help us to do the same. By their lives and their examples, they clean the windshield for us; they clean away the bug blood and the mud, so that we no longer focus on the window, but on the God the window shows us.

The saints whom we celebrate on this day (and the many who are given special days of individual recognition) were people who tried to live according to the Bible as they understood its teachings. Like us, they read it and encountered those troubling visions, those petulant patriarchs, those bloodthirsty psalms, and somehow looked past them and through them to see the God of faith, the God who Incarnate in Jesus said, “Love your enemies, do good to those who hate you, bless those who curse you, pray for those who abuse you.” We extoll the virtues of those saint and we celebrate their lives and their witness because they help us to do the same. By their lives and their examples, they clean the windshield for us; they clean away the bug blood and the mud, so that we no longer focus on the window, but on the God the window shows us. We are straying from our usual lectionary path today because it is one of our Children’s Sundays and we have some younger kids reading the lessons at the 10 a.m. service. So, instead of a long reading from the prophet Joel (RCL Year C, Track 1), we have a brief lesson from the Book of Ben Sira, which is sometimes called Ecclesiasticus. (RCL Year C, Track 2) We thought it would be easier for a child to read.

We are straying from our usual lectionary path today because it is one of our Children’s Sundays and we have some younger kids reading the lessons at the 10 a.m. service. So, instead of a long reading from the prophet Joel (RCL Year C, Track 1), we have a brief lesson from the Book of Ben Sira, which is sometimes called Ecclesiasticus. (RCL Year C, Track 2) We thought it would be easier for a child to read.  I bring you greetings from the people of St. Paul’s Parish, Medina, Ohio, where I am privileged to serve as rector. Nearly all the active members of our congregation know and respect Patrick, and have asked me to convey their congratulations to him and to you, together with the assurance of their prayers, as you continue together in a new ministry only recently begun. Of course, none of them know Sandy, but we offer our greetings and prayers for her diaconal ministry among you, as well.

I bring you greetings from the people of St. Paul’s Parish, Medina, Ohio, where I am privileged to serve as rector. Nearly all the active members of our congregation know and respect Patrick, and have asked me to convey their congratulations to him and to you, together with the assurance of their prayers, as you continue together in a new ministry only recently begun. Of course, none of them know Sandy, but we offer our greetings and prayers for her diaconal ministry among you, as well. In the original Star Trek series, the crew’s uniforms were color coded: gold uniforms were command; red uniforms were engineering and security; and blue uniforms were science and medical. Parish ministry entails all three. So, Patrick, I have a little gift for you — a set of three pairs of official Star Trek color-coded uniform socks to remind you of these aspects of pastoral ministry.

In the original Star Trek series, the crew’s uniforms were color coded: gold uniforms were command; red uniforms were engineering and security; and blue uniforms were science and medical. Parish ministry entails all three. So, Patrick, I have a little gift for you — a set of three pairs of official Star Trek color-coded uniform socks to remind you of these aspects of pastoral ministry. Which brings us, at last, to the blue uniforms, the science and medical corps of the star ship. Mr. Spock the Science officer and Doctor “Bones” McCoy always wore blue. One of the ancient terms that we still use for pastoral ministry is “the cure of souls,” the word “cure” having pretty much the same meaning as it has in medicine. Broadly speaking, this ministry is the care, protection, and oversight of the nourishment and spiritual well-being of the souls committed to the pastor’s care; it may be shared with others, with deacons or with lay ministers, but it is truly the ministry of the parish priest. It is in this “blue shirt” ministry that those wonderful, painful, joyful, intimate moments of grace that I spoke of earlier will happen.

Which brings us, at last, to the blue uniforms, the science and medical corps of the star ship. Mr. Spock the Science officer and Doctor “Bones” McCoy always wore blue. One of the ancient terms that we still use for pastoral ministry is “the cure of souls,” the word “cure” having pretty much the same meaning as it has in medicine. Broadly speaking, this ministry is the care, protection, and oversight of the nourishment and spiritual well-being of the souls committed to the pastor’s care; it may be shared with others, with deacons or with lay ministers, but it is truly the ministry of the parish priest. It is in this “blue shirt” ministry that those wonderful, painful, joyful, intimate moments of grace that I spoke of earlier will happen. We are given three very challenging readings from Holy Scripture this morning. First, there is Jeremiah’s familiar, but radical, prophetic metaphor of God as a potter able to do with the nation of Israel what a potter does with a spoiled piece of work. Second, perhaps the oddest piece of New Testament literature, Paul’s personal letter to a man named Philemon returning a runaway slave whom Paul has converted to Christianity. And, lastly, Luke’s report of Jesus’ radical requirement that his followers must hate their possessions, their families, and even themselves. What I believe is common among these lessons is a call to radical transformation.

We are given three very challenging readings from Holy Scripture this morning. First, there is Jeremiah’s familiar, but radical, prophetic metaphor of God as a potter able to do with the nation of Israel what a potter does with a spoiled piece of work. Second, perhaps the oddest piece of New Testament literature, Paul’s personal letter to a man named Philemon returning a runaway slave whom Paul has converted to Christianity. And, lastly, Luke’s report of Jesus’ radical requirement that his followers must hate their possessions, their families, and even themselves. What I believe is common among these lessons is a call to radical transformation. We are used to thinking of the Book of Isaiah as the work of a single prophet, but it is really three books: First Isaiah, comprising chapters 1-39; Second Isaiah, made up of chapters 40-55; and Third Isaiah, chapters 56-66. These three prophets did their work in three different and distinct periods in Jewish history: the late 8th Century BCE; the mid-6th Century BCE, and the late 6th Century BCE, respectively. This is clear from evidence in their writings: their themes vary and each prophet speaks from a different location. First Isaiah is clearly set in pre-exilic Jerusalem; Second Isaiah was obviously written in Babylon; Third Isaiah speaks from post-exilic Jerusalem. Nonetheless, there is a sense of unity in the writings that make up this book. Phrases and themes recur, and there are linkages later and earlier passages. Today’s reading is from First Isaiah and introduces a topic which will be taken up again by Second and Third Isaiah: what constitutes proper worship?

We are used to thinking of the Book of Isaiah as the work of a single prophet, but it is really three books: First Isaiah, comprising chapters 1-39; Second Isaiah, made up of chapters 40-55; and Third Isaiah, chapters 56-66. These three prophets did their work in three different and distinct periods in Jewish history: the late 8th Century BCE; the mid-6th Century BCE, and the late 6th Century BCE, respectively. This is clear from evidence in their writings: their themes vary and each prophet speaks from a different location. First Isaiah is clearly set in pre-exilic Jerusalem; Second Isaiah was obviously written in Babylon; Third Isaiah speaks from post-exilic Jerusalem. Nonetheless, there is a sense of unity in the writings that make up this book. Phrases and themes recur, and there are linkages later and earlier passages. Today’s reading is from First Isaiah and introduces a topic which will be taken up again by Second and Third Isaiah: what constitutes proper worship?