====================

A sermon offered by the Rev. Dr. C. Eric Funston on the Third Sunday after Pentecost, June 5, 2016, to the people of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Medina, Ohio, where Fr. Funston is rector.

(The lessons for the day are Proper 5C of the Revised Common Lectionary: 1 Kings 17:17-24; Psalm 30; Galatians 1:11-24; and St. Luke 7:11-17. These lessons may be found at The Lectionary Page.)

====================

I am convinced that there is no grief quite so profound as that of a mother whose child has died. I know that fathers in the same situation feel a nearly as intense sorrow at the death of their sons or daughters, but having spent time with grieving parents, I am convinced that the grief of a mother faced with the loss of her child is the deepest sadness in human experience.

I am convinced that there is no grief quite so profound as that of a mother whose child has died. I know that fathers in the same situation feel a nearly as intense sorrow at the death of their sons or daughters, but having spent time with grieving parents, I am convinced that the grief of a mother faced with the loss of her child is the deepest sadness in human experience.

About nine hundred years before the time of Jesus of Nazareth, the prophet Elijah spoke the word of God during the reign of King Ahab and Queen Jezebel. Jezebel was a foreigner who worshipped the god Ba’al and this was an abomination in Elijah’s eyes, and he was not remiss in letting the queen and everyone else know what he thought of that. He challenged Ahab about his wife and her religion, something the king did not appreciate. So Elijah fled the country; the First Book of Kings tells us that he did so at the command of God, who apparently wished to preserve the life of his prophet.

God sent Elijah during a time of famine to a widow in the Phoenician town of Zarephath. The woman was surprised by Elijah’s demand, pointing out that she had just enough flour and oil to make a last meal for her and her son, after which they expected to die of starvation. Elijah (as we heard) told her not to worry, that if she would feed Elijah, her canister of flour and her flask of oil would never run out until the famine ended. Sure enough that proved to be true. But not long after that meal, her son died.

In anger, out of the depths of that profound sorrow, she lashed out at Elijah: “What have you against me, O man of God? You have come to me to bring my sin to remembrance, and to cause the death of my son!” Elijah, faced with his hostess’s grief and anger, was also angered by the boy’s death. “He cried out to the Lord, ‘O Lord my God, have you brought calamity even upon the widow with whom I am staying, by killing her son?’”

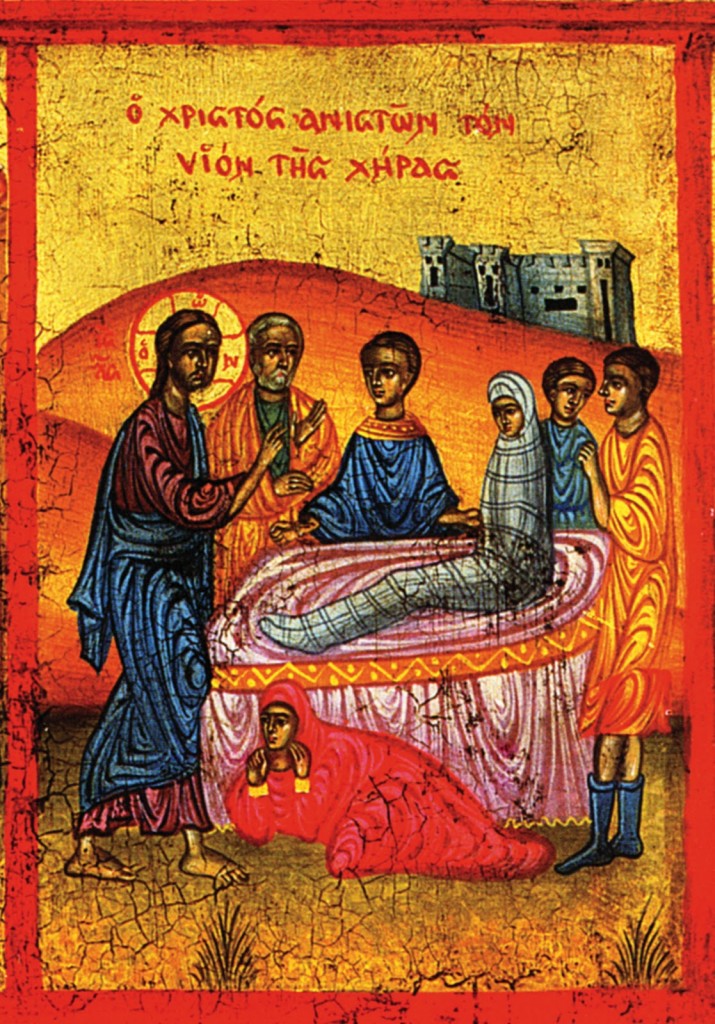

Nearly a millennium later, Luke tells us that Jesus also encountered another grieving mother. Entering the town of Nain, he encountered a funeral procession for a young man and was confronted by the deep maternal sorrow of his widowed mother. In our English translation, Luke says that Jesus felt compassion for the woman. The Greek word is a little earthier: splagchnizomai. It is derived from the word splagchna, which means “entrails” or “intestines”. It means, literally, to have one’s gut wrenched; it says that one has a feeling deep in one’s gut, the deepest of all human emotions, the kind of feeling that is physical as much as emotive. The best definition I’ve ever heard of splagchnizomai is that it is a lurching feeling deep in your gut that compels you to do something. That is a great description for both Jesus’ compassion for the widow of Nain and Elijah’s anger at the death of the son of the widow of Zarephath.

Today, in follow up to our Ninth Annual Gentlemen’s Cake Auction, we welcome and honor Michelle Powell, a single mother of two, who in the summer of 2000, had that sort of feeling deep in her gut that compelled her to do something. With limited resources, offering nothing more than a simple meal and a game of kickball at the local park, she started Let’s Make a Difference and began a journey that would ultimately change her life and positively impact the lives of many at-risk children in need in the Medina community. The mission of Let’s Make a Difference is “to provide positive social growth in the lives of children in need through educational, spiritual and creative experiences, promoting the fact that each person can make a difference.” This summer Let’s Make a Difference will offer character development activities, field trips, academic enrichment, arts and crafts, games and lots of fun, and make a huge difference in the lives of many of Medina’s underprivileged children.

We also welcome and pay tribute to retired educator Carol Andregg. In 2007, as an outgrowth of Let’s Make a Difference, Michelle and Carol started an after-school program for students at Claggett Middle School. Called Achieving Connections through Education (or “ACE”), the program assists students on four days of a typical five-day school week with daily homework assignments, longer term projects, behavioral issues, and developing respect for self and others. ACE has made a significant impact in the lives of their students, many of whom have successfully completed high school and gone on to college. Today, we honor and support Michelle, Carol, Let’s Make a Difference, and Achieving Connections through Education with a grant of $2,635, the total amount raised through this year’s cake auction. (See the Let’s Make a Difference Website)

Writing about the gospel story we have heard this morning, the Rev. Lia Scholl, pastor at Richmond Mennonite Fellowship in Richmond, Virginia, has offered what she calls a four-lesson, do-it-yourself guide to healing like Jesus.

#1: Pay Attention

The first lesson? We have to be paying attention. Jesus is walking along, sees a funeral procession and notices the mother of the deceased boy or man. He notices her.

#2: Give a Crap

The second lesson? Give a crap. How easy it would have been for Jesus to just walk on by. No one expected him to heal every sick or dead person who crossed his path. Jesus gave a crap.

#3: Be Willing to Feel

The third lesson? We have to be willing to feel. The NIV translates this passage as “his heart went out to her.” We have to be willing to hurt. That’s what compassion is. To share in someone’s pain.

#4: Healing Can Happen

The fourth lesson? We just walk up to someone who is dead and we command that they get better. It works! It really works. No, it doesn’t.

The fourth lesson is that healing can happen if the other things are in place. It may not be supernatural, immediate healing. But healing can happen . . . .

(How to Heal Like Jesus: Luke’s DIY Guide to Healing People)

I think Pastor Scholl has pretty well encapsulated everything we need to learn from these stories of mothers whose children died and from the ministry done in each case by Elijah and Jesus: pay attention, care so much you do something, be willing to be hurt, and trust that healing can happen. That’s what Michelle and Carol have done and why Let’s Make a Difference is making a difference. That’s what good people throughout time have done.

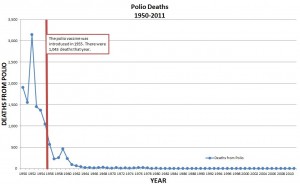

The year that I was born was the worst of the mid-20th Century polio epidemic; about 55,000 Americans contracted the disease that year and more than 3,100 died, mostly children. As a society, we decided that that much illness and death was simply unacceptable, and an all-out effort was underway to put an end to it. Within just a few years, Jonas Salk and his team developed the vaccine which ended the epidemic; a few years later, the Sabin oral vaccine was developed and polio has been just about eradicated throughout the world. (Graphic from Polio Cases, Deaths, and Vaccination Rates.)

The year that I was born was the worst of the mid-20th Century polio epidemic; about 55,000 Americans contracted the disease that year and more than 3,100 died, mostly children. As a society, we decided that that much illness and death was simply unacceptable, and an all-out effort was underway to put an end to it. Within just a few years, Jonas Salk and his team developed the vaccine which ended the epidemic; a few years later, the Sabin oral vaccine was developed and polio has been just about eradicated throughout the world. (Graphic from Polio Cases, Deaths, and Vaccination Rates.)

We are now in the midst of an even more deadly epidemic in this country, an epidemic of gun violence, and that is the point of the odd-colored stole I am wearing today.

On January 21, 2013, Hadiya Pendleton, a 15-year-old high school student from the south side of Chicago, marched with her school’s band in President Obama’s second inaugural parade. One week later, Hadiya was shot and killed. She was shot in the back while standing with friends inside Harsh Park in Kenwood, Chicago, after taking her final exams. She was not the intended victim; the perpetrator, a gang member, had mistaken her group of friends for a rival gang.

On January 21, 2013, Hadiya Pendleton, a 15-year-old high school student from the south side of Chicago, marched with her school’s band in President Obama’s second inaugural parade. One week later, Hadiya was shot and killed. She was shot in the back while standing with friends inside Harsh Park in Kenwood, Chicago, after taking her final exams. She was not the intended victim; the perpetrator, a gang member, had mistaken her group of friends for a rival gang.

On Hadiya’s birthday, June 2, her friends chose to wear orange, the color hunters wear in the woods to protect themselves, to remember her life. What started in a south side high school to celebrate Hadiya has turned into a nationwide movement to honor all lives cut short by gun violence. Now, June 2 each year is National Gun Violence Awareness Day, and those who participate wear orange to celebrate of life, to raise awareness of the scourge of gun violence, and to call for action to help save other lives from gunfire. (See Wear Orange)

This year, beginning here in Ohio, Episcopal clergy and clergy of many other denominations, including many of our bishops, have decided to wear out-of-the-ordinary orange vestments for the same purpose. (See Episcopal News Service) Too many of us have sat with and held the hands of too many mothers, too many fathers whose children have died, too many widows of Zarephath, too many widows of Nain. We have felt the rage of Elijah and the gut-wrenching compassion of Jesus but, unlike them, we are unable to change the circumstances. If we could have prevented those deaths, we would; if we could raise those dead children, we would. We can’t. But what we can do is raise awareness.

Here are just a few of the realities of the gun violence epidemic in this country:

- On an average day in America, 91 people die from gun shots. If you compute that out, you’ll find that the number of deaths per year is more than 33,000; that is ten times the number of deaths from polio in the worst year of that epidemic. (See Everytown for Gun Safety)

- Sometimes we hear people claim that the risk of gun death, especially the risk to children and teens, is higher in urban areas than in the suburbs or in rural communities. The fact is that the risk of gun death is the same in all areas, although the underlying reason for the death may be different: “Youth (ages 0 to 19) in the most rural U.S. counties are as likely to die from a gunshot as those living in the most urban counties. Rural children die of more gun suicides and unintentional shooting deaths. Urban children die more often of gun homicides.” (See Brady Campaign: About Gun Violence)

- 64% of all gun deaths are suicides. (See Everytown for Gun Safety) “Someone with access to firearms is three times more likely to commit suicide” than someone living in a home where there are no guns. (See Access to Guns Increases Risk of Suicide)

- Last week there was an enormous amount of news coverage about the shooting and killing of the silver-back ape Harambe at the Cincinnati Zoo. While that was a tragedy, I suggest to you that even more tragic were the three shootings of human beings in Ohio which were statistically likely to have happened the same day. Did you know that? That, statistically, an Ohio resident is shot to death every eight hours? In 2011 in this state “an average of one aggravated assault with a firearm [occurred] every two and a half hours.” (See Fact Sheet: Ohio Gun Violence)

- Did you know that during the current year alone there have been 121 mass shootings (in which four or more persons were injured or killed) in the United States? That’s more than five per week, and more than half of those were the result of a family or domestic dispute; very many of the victims of those shootings were children. (See Gun Violence Archive)

- Did you know that since the Sandy Hook school shooting in Newtown, Connecticut, on December 14, 2012, there has been at least one on-campus shooting in a school or college nearly every week? More than 160 incidents in which 59 people were killed and 124 were injured. (See Analysis of School Shootings)

- Did you know that seven children and teens (age 19 or under) are killed with guns in the U.S. on an average day? (See Brady Campaign: About Gun Violence)

Seven mothers every day suffer the profound, gut-wrenching, soul-deep sorrow of the widows of Zarephath and Nain because of the preventable deaths of their children.

Gun violence is an epidemic far worse than the polio epidemic. Unlike the polio epidemic, however, it is one about which we need do no research to stem! We know the cause and we know how to stop it. If guns were a disease that killed 30,000 or more, this epidemic would have ended long ago. And yet we take no action to put an end to it.

Scholars often debate the historical accuracy of stories from the Bible; these two stories today get a lot of attention in that regard. But whether they are historically accurate or not is really not the point. These stories have a lesson to teach. As theologian Bill Loader says,

Whether or not one wants to defend the historicity of such accounts or is happy to see them as legendary expressions of faith, they still have a role within a broader perspective. [The story of Jesus raising the son of the widow of Nain], in particular, deserves to be allowed its symbolic potential. The ministry of Jesus and ours is about addressing real human need and it is about compassion. This is indeed his mission, God’s mission.

Such compassion and caring in action has few short-cuts to success, if any. A cross stands in the road, which unveils reality for both the carers and the world in need of care. In the midst of the complexity of human need is hope and the possibility of renewal and life. It is built on the foundation that all people are of value and none is to be dismissed or despised. Our world still needs that kind of good news and our challenge is to become it and help others become it. (First Thoughts on Year C Gospel Passages from the Lectionary)

Our gift to the good people of Let’s Make a Difference and the marvelous work they do with at-risk children in Medina is a significant step in God’s mission of compassion, but it is only one step. These children, our children, our grandchildren are at risk every day from dangers, some of which we cannot know or imagine, but one of which we know all too well, the epidemic of preventable gun violence.

About the story of Elijah and the dead boy in Zarephath, Presbyterian pastor MaryAnn McKibben Dana, author of Sabbath in the Suburbs, writes:

As a minister of the gospel, I cannot bring ailing boys back to life – how I wish I could. But this story convicts me that while I am called to offer presence and a message of grace to people hungering for wholeness and justice, presence and eloquent words are not enough. This widow would surely offer an “Amen” to James when he wrote, “If a brother or sister is naked and lacks daily food, and one of you says to them, ‘Go in peace; keep warm and eat your fill’, and yet you do not supply their bodily needs, what is the good of that?” Elijah is not off the hook simply because the jars of meal and oil have not run out. He must do all he can for the continued well-being of her son. (Political Theology Today)

We are not let off the hook by our grant to Let’s Make a Difference; we must do all we can for the continued well-being of the children they serve and of all the children of our community and our nation. That means being aware of and working for the end of the epidemic of gun violence which threatens them.

Carolyn Winfrey Gillette is another Presbyterian elder who writes hymns. Her hymn God of Mercy, You Have Shown Us was written at the request of the Presbyterian Peacemaking Program for an International Peace Day in September, 2009. I will close with her lyrics as a prayer:

God of mercy, you have shown us ways of living that are good:

Work for justice, treasure kindness, humbly journey with the Lord.

Yet your people here are grieving, hurt by weapons that destroy.

Help us turn to you, believing in your way that brings us joy.On a street where neighbors gather, shots are heard; a young girl dies.

On a campus, students scatter as the violence claims more lives.

In a family filled with anger, tempers flare and shots resound.

God of love, we weep and wonder at the violence all around.God, we pray for those who suffer when this world seems so unfair;

May your church be quick to offer loving comfort, gentle care.

And we pray: Amid the violence, may we speak your truth, O Lord!

Give us strength to break the silence, saying, “This can be no more!”God, renew our faith and vision, make us those who boldly lead!

May we work for just decisions that bring true security.

Help us change this violent culture based on idols, built on fear.

Help us build a peaceful future with your world of people here.

There is no grief so profound as that of the widows of Zarephath and Nain, the grief a mother whose child has died. Let us do all in our power to prevent that grief whenever we can. Let us learn from Jesus: pay attention to what is happening, care so much we do something, be willing to be hurt, and trust that this epidemic can be healed. And let us make a difference! Amen.

====================

A request to my readers: I’m trying to build the readership of this blog and I’d very much appreciate your help in doing so. If you find something here that is of value, please share it with others. If you are on Facebook, “like” the posts on your page so others can see them. If you are following me on Twitter, please “retweet” the notices of these meditations. If you have a blog of your own, please include mine in your links (a favor I will gladly reciprocate). Many thanks!

====================

Father Funston is the rector of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Medina, Ohio.

Why are we here? Well, for a wedding, of course. But, more specifically, you may be wondering why an old Episcopal priest from Ohio is here in an 18th Century Puritan meeting house trying to do 21st Century Anglo-Catholic ritual. The short answer is that Chris asked me to. Chris was my music director at St Paul’s Church in Medina, Ohio, when he was a student at Oberlin (which his mother reminded me yesterday was just a few weeks ago), and we’ve been friends ever since.

Why are we here? Well, for a wedding, of course. But, more specifically, you may be wondering why an old Episcopal priest from Ohio is here in an 18th Century Puritan meeting house trying to do 21st Century Anglo-Catholic ritual. The short answer is that Chris asked me to. Chris was my music director at St Paul’s Church in Medina, Ohio, when he was a student at Oberlin (which his mother reminded me yesterday was just a few weeks ago), and we’ve been friends ever since.  There’s a lady who’s sure

There’s a lady who’s sure In Jerusalem, just outside the walled Old City to the south is a church built on the place where the house of Caiaphas, the high priest who oversaw Jesus’ crucifixion, is believed to have been. The church is named St. Peter in Gallicantu; the name is from the Latin meaning, “St. Peter where the rooster crowed.” It is a reference, of course, to Peter’s three denials of Christ in the courtyard of the high priest’s house.

In Jerusalem, just outside the walled Old City to the south is a church built on the place where the house of Caiaphas, the high priest who oversaw Jesus’ crucifixion, is believed to have been. The church is named St. Peter in Gallicantu; the name is from the Latin meaning, “St. Peter where the rooster crowed.” It is a reference, of course, to Peter’s three denials of Christ in the courtyard of the high priest’s house.  Every year on the Second Sunday of the Easter season, we read the story from John’s Gospel of Thomas’s refusal to accept the testimony of his fellow disciples, but in each year of the Lectionary Cycle, it is coupled with different lessons from the Book of Acts and a different epistle lesson. So this year, in Year C of the cycle, we have heard of the confrontation between Peter and the high priest about the apostles’ teaching in the Temple, and we have heard part of the introduction of John of Patmos’ Revelation.

Every year on the Second Sunday of the Easter season, we read the story from John’s Gospel of Thomas’s refusal to accept the testimony of his fellow disciples, but in each year of the Lectionary Cycle, it is coupled with different lessons from the Book of Acts and a different epistle lesson. So this year, in Year C of the cycle, we have heard of the confrontation between Peter and the high priest about the apostles’ teaching in the Temple, and we have heard part of the introduction of John of Patmos’ Revelation.  Litigation attorneys and fishermen have something in common… We like to tell stories. Fishermen tell about “the one that got away.” Trial lawyers prefer to tell about the ones we got!

Litigation attorneys and fishermen have something in common… We like to tell stories. Fishermen tell about “the one that got away.” Trial lawyers prefer to tell about the ones we got! They have had their dinner during which, predicting his death, Jesus has instructed them to share bread and wine again and again in his memory. Jesus has washed their feet. He has given them his New Commandment, “Love one another.” Now, dinner ended, it is time for a stroll in the garden.

They have had their dinner during which, predicting his death, Jesus has instructed them to share bread and wine again and again in his memory. Jesus has washed their feet. He has given them his New Commandment, “Love one another.” Now, dinner ended, it is time for a stroll in the garden. It’s April! When did that happen?

It’s April! When did that happen?