====================

A homily offered by the Rev. Dr. C. Eric Funston on the Seventeenth Sunday after Pentecost, September 11, 2016, to the people of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Medina, Ohio, where Fr. Funston is rector.

(The lessons for the day are Proper 19C of the Revised Common Lectionary: Exodus 32:7-14; Psalm 51:1-11; 1 Timothy 1:12-17; and St. Luke 15:1-10. These lessons may be found at The Lectionary Page.)

====================

I’d like you all to take your Prayer Books in hand and turn with me to page 855 which is way in the back of the book in the section called The Catechism or Outline of the Faith. At the top of the page are three questions about the mission of the church and the answers to those questions that we as Episcopalians teach. I’m going to read the questions; I’d like you to read the answers:

I’d like you all to take your Prayer Books in hand and turn with me to page 855 which is way in the back of the book in the section called The Catechism or Outline of the Faith. At the top of the page are three questions about the mission of the church and the answers to those questions that we as Episcopalians teach. I’m going to read the questions; I’d like you to read the answers:

Q. What is the mission of the Church?

A. The mission of the Church is to restore all people to unity with God and each other in Christ.

Q. How does the Church pursue its mission?

A. The Church pursues its mission as it prays and worships, proclaims the Gospel, and promotes justice, peace, and love.

Q. Through whom does the Church carry out its mission?

A. The church carries out its mission through the ministry of all its members.

Following those questions are a few more about the specific ministry of the various orders (lay persons, bishops, priests, and deacons); I invite you to read those on your own.

For now, just keep in mind that the church’s mission is to restore people to unity with God and one another; we have a word for that – it’s called reconciliation. Remember that the church carries out that mission in prayer, worship, and proclamation, and by promoting justice, peace, and love. And, finally, remember that the church does so not as an institution, but through the individual ministries of its members, not as a collective like the Borg of Star Trek but as individuals with distinctive skills, talents, and interests (as Capt. Kathryn Janeway of the USS Voyager often instructed the former Borg drone Seven-of-Nine).

As you keep all that in mind, let me tell you a story about myself as a younger man, about thirty years younger. Back then I was not ordained; I was a practicing attorney living in Las Vegas, Nevada, with Evelyn and our children. Patrick was three years of age and Caitlin was one. One day I decided to take my son to the circus; more accurately, I took him to Circus Circus Casino. Now normally one does not take a 3-year-old to a casino, but Circus Circus is (or at least was) a special sort of casino. Housed in a building made to look like a “big top”, it had a mezzanine circling the gaming floor and on this mezzanine was an arcade filled with all the circus and carnival attractions you can name. Over the gaming floor was a trapeze rig on which gymnasts swung and flew with reckless abandon, while on the mezzanine midway barkers sought to attract patrons to shooting galleries, ring-toss games, and the like. My toddler was in awe of the whole thing.

We stopped for a few minutes to watch the trapeze artists and at some point I looked down and discovered that my son was no longer at my side. He was right there – and then he wasn’t! I know that most, if not all parents, have experienced something similar. That moment when your child has gone missing and you begin to experience every emotion known to humankind . . . in spades! Adrenaline courses through not only your body but your soul; you are in a physical and spiritual panic! “Where is my child!?!?” Fear and worry, hope and hopelessness, confusion and sadness . . . it’s all there, all jumbled together. It’s almost impossible to function and yet function you must; you have to find your child!

As it turned out, Patrick was only about eight feet away. The trapeze wasn’t nearly as exciting as the ring-toss game where, if his father had a good eye and a steady hand he might throw a plastic ring around a jelly jar and Patrick would get the gold fish living therein. When, after an eternity of maybe two or three minutes, I finally found him, a whole new rush of mixed emotions set in – relief, anger, joy, love – and I found myself kneeling on the floor holding him by the shoulders and yelling at him, adding to the circus noise of the crowded casino.

A security guard about my age, probably a father himself, had seen my panicked search and started to come over, arriving about the same time that I’d found Patrick. As I was shouting my lecture about not leaving Dad’s side, the guard put his hand on my shoulder . . . and that’s all it took. It calmed me down; the anger fled and the relief, joy, and love flooded in. I hugged my son tightly to me and vowed never to lose him again.

If you’re a parent, perhaps you’ve had a similar experience; as I said, I imagine most if not all parents have done so. Or perhaps you’ve been through that situation where you’ve worked for days on a project at work or school only to have a co-worker or a fellow student do something that renders all your effort of no worth at all. You’ve just lost all that time and work, and the feeling of futility that washes over you is just mind-numbing and drains you of all sense of worth and well-being. If you could, you’d drop-kick that colleague right out the front door. But then, perhaps another workmate, perhaps a supervisor or a teacher, makes a gesture or says a word and you realize that you really have no reason for anger. This is just the way things go sometimes and whatever the other worker or student may have done probably wasn’t done to hurt you; that’s just life. You pick up and you move on.

If you’ve had experiences like these, you know how the shepherd or the woman in Jesus’ parables this morning felt. You know how Yahweh felt at Sinai in our story from the Book of Exodus.

In the latter, Moses has left the Hebrews encamped at the base of Mt. Sinai while he has climbed the mountain to converse with Yahweh; he will eventually be bringing down the Law, the Commandments etched on stone by God’s own self. Moses is on the mountain for forty days and forty nights during which the Hebrews begin to feel themselves abandoned. They probably go through that whole gamut of emotions that a lost child, or a parent looking for a lost child, feels . . . but this story really isn’t about them . . . . Anyway, they feel abandoned because of Moses’ long absence and so they turn to his brother, Aaron the Priest, and say, “Make us a god!”

Aaron complies; Aaron seems like the type who is always easy going and willing to compromise and so he does as they ask, taking their jewelry and gold money and fashioning a god for them, the Golden Calf. This comforts them and so they begin to celebrate with revelry, the Bible tells us; that’s singing and dancing and some things we don’t generally talk about in church.

Meanwhile, Yahweh distracted by his conversation with Moses doesn’t notice his children wandering off. When he looks down, however, he finds them gone and, worse, when he finds them they aren’t just distracted by a ring-toss game and some goldfish. They are worshiping an idol!

Shauna Hannan, Associate Professor of Homiletics at Pacific Lutheran Theological Seminary in Berkeley, California, says that we should stop referring to this text as the “golden calf” incident and begin calling it the “God changes God’s mind at the request of Moses” incident. (Hannan) One of the things that strikes me about this incident is how very much Yahweh acts like an angry parent in this episode.

Something I found myself doing early in parenthood was referring to our kids as “my son” or “my daughter” when they were behaving well, but when they misbehaved I would turn to Evelyn and say, “Do something about your son (daughter)!” Back in Chapter 20, Yahweh said to the Hebrews, “I am the Lord your God, [I’m the one] who brought you out of the land of Egypt,” (v. 2) but now he says to Moses, “Your people, whom you brought up out of the land of Egypt, have acted perversely.” (32:7) I can really relate to Yahweh’s doing that!

And not only does God sort of disown these folks! Prof. Hannan points out that

God calls them names: stiff-necked people. And worse, God wants to be left alone to wallow in anger and to “consume” the idolaters. If that is not enough, God seems to bribe Moses to leave him alone (32:10). If Moses does so, God will make of him a great nation. Anger, tirade, blame, name-calling, destruction, bribery; this is not God at God’s best. (Hannan)

But Moses steps in like that security guard at Circus Circus, or like the supervisor at work or the teacher at school, and says a calming word. “Turn from your fierce anger,” he says, “Calm down. Remember your promises to Abrahan, Isaac, and Jacob.” Moses figuratively lays a hand on Yahweh’s shoulder. Callie Plunket-Brewton, who teaches at the University of North Alabama, says Moses here serves as a model for the Church, bearing witness to God’s faithful compassion and urging reconciliation between God and God’s people, although in this peculiar circumstance it is Yahweh himself to whom Moses is witnessing! (Plunket-Brewton)

Five years ago, on the Sunday closest to the anniversary of the September 11 tragedy at the World Trade Center, at the Pentagon, and near Shanksville, Pennsylvania, of which today is the 15th anniversary, I was invited to preach at St. Paul’s Church of Ireland Parish in the town of Banagher, County Offaly, Ireland. The lessons for that day were from the first chapter of the Book of Proverbs, in which Lady Wisdom cries out to passersby, “How long will you love being naive?” (Prov. 1:22) and from the eighth chapter of Mark’s Gospel in which Peter tries to stop Jesus from going to Jerusalem and Jesus responds, “Get behind me, Satan! For you are setting your mind not on divine things but on human things.” (Mk 8:33)

I suggested to my Irish audience that there is a parallel between the way the British authorities responded to Ireland’s Easter Uprising of 1916 and the way we in America responded to the actions of Al-Qaeda on September 11. They and we were naive, and when they and we experienced the tragic loss of life and the overwhelming loss of control that those events represented, we did, indeed, set our minds on human things, on revenge and retribution, rather than on divine things, on restoring all people to unity with God and each other, on promoting justice, peace, and love. So Ireland found itself in nearly a century of sectarian strife and eventually the deadly and devastating Troubles of Northern Ireland. And we have found ourselves 15 years later still battling terrorists, still fighting in the Gulf States, still engaged in Afghanistan and Iraq in the longest armed combat in our nation’s history, and trying not to get deeply involved in the directly consequent civil war in Syria.

If only someone had raised their voice, if only someone had laid their hands on our nations’ shoulders and said, “Turn from your fierce anger. Calm down. Remember your promises . . . .” Eventually the Irish and the British were able to end their bitter relationship and the Troubles which made Northern Ireland a hell-on-earth; we hope and pray that we will be able to do the same in and with the Gulf States and those who live there.

I said that the reading from Exodus is really not a story about the Hebrews. It is a story about God, about Yahweh, a god who understands those feelings of loss, who knows what it is to feel loss-engendered anger and to want retribution and revenge, and who turns away from those things to seek reconciliation instead.

The parables that Jesus tells in our selection from Luke’s Gospel are also stories about God, about God and loss, and not (as we often think) about us. Though they are often called the parables of the “lost sheep” and the “lost coin,” they ought to be called the parable of the shepherd who went in search of a sheep and of the woman who cleaned her house looking for a coin. That would take the focus off the thing that is loss and put it properly on the one who does the finding.

However, we do have to consider the things that are lost and what that means. Karoline Lewis, who writes a weekly internet column about the lectionary texts entitled Dear Working Preacher, noted this week that “the state of being lost is a rather ambiguous determination in life.” Being lost can mean being misplaced, or misdirected, or misguided, or wasted. “A definition of ‘lost’ seems as broad as its incidences: unable to be found; not knowing where you are or how to get to where you want to go; unable to find your way; no longer held, owned, or possessed.” (Lewis)

On Thursday afternoon I was driving to Brook Park and listening to Terry Gross’s NPR show Fresh Air as she interviewed an author named Steve Silberman about his book NeuroTribes: The Legacy of Autism and the Future of Neurodiversity. (Available online) As they talked about the autism spectrum, it occurred to me that there might be a similar continuum of “lostness” that could help us understand these bible lessons. It seems to me that at one end of such a lostness spectrum are the Hebrews at the foot of Mt. Sinai. They are lost by reason of their own decision; they are, as Yahweh said, stiff-necked people and their lostness is the consequence of their own actions, their own impatience, rejection, and alienation. In short, the Hebrews at the foot of Mt. Sinai are lost because of sin.

At the other end of the spectrum is the coin, about which we might ask, “How does a coin sin? How does a coin lose itself?” and the simple answer is that it can’t.

And somewhere in the middle of our lostness continuum is the sheep, who wandered away from the flock not out of rejection or alienation, but simply because sheep are rather dull-witted and naive. It has wandered off not through sinful intent, but through silly innocence.

The wonderful thing that these stories demonstrate is that the mechanism of lostness, the reason the Hebrews, the sheep, or the coin are lost, is irrelevant. What these stories show is that the one who feels their absence, the one who is concerned about their lostness, God, is going to find them. Influenced by the intervention of Moses, by his witness to God’s own ministry of reconciliation, “the Lord changed his mind about the disaster that he planned to bring on his people,” and instead restored Godself to unity with them. The shepherd sought and found the lost sheep and rejoiced. The woman sought and found the lost coin and rejoiced. The emphasis in all these stories is on the finding and the restoration of relationship, on the one committed to that end.

Jennifer Copeland, a Methodist minister, wrote several years ago in The Christian Century magazine:

The lost sheep and the lost coin are more than the prized possessions of their owners; they are also parts of a whole. The sheep belongs to the flock and the coin to the purse; without them the whole is not complete. The search, then, is a quest for restoration and wholeness. In this sense, all of us who are part of God’s creation should be just as anxious as God until the lost are restored and we are made whole again by their presence. (Clean Sweep, The Christian Century, September 7, 2004, p. 20)

Prof. Hannan suggests that this emphasis on wholeness is also the “shocking and profoundly hopeful news” of the Exodus passage, the news “that God sticks with us; God continues to claim us as God’s own despite” everything. (Hannan)

On this 15th anniversary of those terrible events that are summed up in the simple numbers “9-11,” in this 13th year of armed conflict that has flowed from them, let us remember that our mission as a church, our mission as individual members of the church, has that same emphasis of reconciliation and wholeness:

The mission of the Church is to restore all people to unity with God and each other in Christ. The Church pursues its mission as it prays and worships, proclaims the Gospel, and promotes justice, peace, and love. The church carries out its mission through the ministry of all its members.

In today’s Daily Office gospel reading from Matthew, Jesus admonishes his hearers, “Be reconciled to your brother or sister.” (Matt 5:24b) I can think of no better way to memorialize all who died September 11, 2001, and in the conflict and violence that has followed.

To close, I would like to offer a prayer for this anniversary co-authored by my friends Deacon Scott Elliott of the Diocese of Chicago and Fr. Bob Winter, a retired priest of this diocese.

Let us pray:

O God of mercy, justice, and love, you have taught us to love even those with whom we are at enmity: As we gather in the Name of your Son to celebrate your goodness and grace, we remember the great evil done in your Name on this day. In your mercy, relieve our hearts of the burden of shock and horror and help us to remember that we, your children, are likewise called to be merciful; help us, as children of the Just One, to respond to your call to be people of justice; help us, as the beneficiaries of your love, to remember your command to love the whole world in your Name. All this we ask in the Name of the Prince of Peace. Amen.

====================

A request to my readers: I’m trying to build the readership of this blog and I’d very much appreciate your help in doing so. If you find something here that is of value, please share it with others. If you are on Facebook, “like” the posts on your page so others can see them. If you are following me on Twitter, please “retweet” the notices of these meditations. If you have a blog of your own, please include mine in your links (a favor I will gladly reciprocate). Many thanks!

====================

Father Funston is the rector of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Medina, Ohio.

The story of the “unjust judge” has to be one of the most confusing of Jesus’ parables related in any of the Gospels. In every bible study group I have ever been a part of someone will want to know how the “unjust judge” could possibly represent God . . . .

The story of the “unjust judge” has to be one of the most confusing of Jesus’ parables related in any of the Gospels. In every bible study group I have ever been a part of someone will want to know how the “unjust judge” could possibly represent God . . . .  For ten months, since the First Sunday of Advent 2015, we have been in Lectionary Year C, during which we’ve been following texts from the Gospel according to Luke. Luke’s Gospel , after telling of his birth and infancy, sets out Jesus’ original mission statement, which he adopted from the Prophet Isaiah and proclaimed in his hometown synagogue:

For ten months, since the First Sunday of Advent 2015, we have been in Lectionary Year C, during which we’ve been following texts from the Gospel according to Luke. Luke’s Gospel , after telling of his birth and infancy, sets out Jesus’ original mission statement, which he adopted from the Prophet Isaiah and proclaimed in his hometown synagogue:![Dives and Lazarus. Psalter (Munich Golden Psalter). England [Gloucester?], 1st quarter of the 13th century.](http://thefunstons.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/Lazarus-and-Dives-300x264.jpg) We could, I suppose, spiritualize the story of Lazarus and the rich man. We could, but if we did we would be twisting it out of shape. This is not a spiritual story. This is a bare-knuckled street-brawl of a story about wealth, about money and possessions, about someone who had plenty and about someone who had none. If we are going to honor the biblical text, we cannot spiritualize this tale; we have to deal with it as it is given us, as a story about money.

We could, I suppose, spiritualize the story of Lazarus and the rich man. We could, but if we did we would be twisting it out of shape. This is not a spiritual story. This is a bare-knuckled street-brawl of a story about wealth, about money and possessions, about someone who had plenty and about someone who had none. If we are going to honor the biblical text, we cannot spiritualize this tale; we have to deal with it as it is given us, as a story about money. I’d like you all to take your Prayer Books in hand and turn with me to page 855 which is way in the back of the book in the section called The Catechism or Outline of the Faith. At the top of the page are three questions about the mission of the church and the answers to those questions that we as Episcopalians teach. I’m going to read the questions; I’d like you to read the answers:

I’d like you all to take your Prayer Books in hand and turn with me to page 855 which is way in the back of the book in the section called The Catechism or Outline of the Faith. At the top of the page are three questions about the mission of the church and the answers to those questions that we as Episcopalians teach. I’m going to read the questions; I’d like you to read the answers: “Whoever comes to me and does not hate father and mother, wife and children, brothers and sisters, yes, and even life itself, cannot be my disciple. * * * None of you can become my disciple if you do not give up all your possessions.”

“Whoever comes to me and does not hate father and mother, wife and children, brothers and sisters, yes, and even life itself, cannot be my disciple. * * * None of you can become my disciple if you do not give up all your possessions.” Our first lesson today is from a book with the wholly amazing title The Book of the All-Virtuous Wisdom of Joshua ben Sira, usually (and mercifully) shortened to Sirach. It is accepted as part of the Christian biblical canon by Roman Catholics, the Eastern Orthodox, and most of the Oriental Orthodox churches. In our Anglican tradition, it is not accepted as canonical, but we do read it “for example of life and instruction of manners;” however, it cannot be used to establish any doctrine. (Article VI of the Articles of Religion, 1801) The book is in the tradition known as “wisdom literature;” basically, it is a collection of ethical teachings closely resembling the canonical Book of Proverbs, and serving the same function.

Our first lesson today is from a book with the wholly amazing title The Book of the All-Virtuous Wisdom of Joshua ben Sira, usually (and mercifully) shortened to Sirach. It is accepted as part of the Christian biblical canon by Roman Catholics, the Eastern Orthodox, and most of the Oriental Orthodox churches. In our Anglican tradition, it is not accepted as canonical, but we do read it “for example of life and instruction of manners;” however, it cannot be used to establish any doctrine. (Article VI of the Articles of Religion, 1801) The book is in the tradition known as “wisdom literature;” basically, it is a collection of ethical teachings closely resembling the canonical Book of Proverbs, and serving the same function. Our reading from the Book of Isaiah today is the second half of chapter 58, a chapter which begins with God ordering the prophet to “Shout out,” to “do not hold back,” to “lift up [his] voice like a trumpet” with God’s answer to a question asked by the people of Jerusalem: “Why do we fast, but you do not see? Why humble ourselves, but you do not notice?” (Isaiah 58:1,3a)

Our reading from the Book of Isaiah today is the second half of chapter 58, a chapter which begins with God ordering the prophet to “Shout out,” to “do not hold back,” to “lift up [his] voice like a trumpet” with God’s answer to a question asked by the people of Jerusalem: “Why do we fast, but you do not see? Why humble ourselves, but you do not notice?” (Isaiah 58:1,3a) In philosophy and theology there is an exercise named by the Greek word deiknumi. The word simply translated means “occurrence” or “evidence,” but in philosophy it refers to a “thought experiment,” a sort of meditation or exploration of a hypothesis about what might happen if certain facts are true or certain situations experienced. It’s particularly useful if those situations cannot be replicated in a laboratory or if the facts are in the past or future and cannot be presently experienced. St. Paul uses the word only once in his epistles: in the last verse of chapter 12 of the First Letter to the Corinthians, he uses the verbal form when he admonishes his readers to “strive for the greater gifts. And I will show you [deiknuo, ‘I will give you evidence of’] a still more excellent way.” It is the introduction to his famous treatise on agape, divine love, a thought experiment (if you will) about the best expression, the “still more excellent” expression of the greatest of the virtues.

In philosophy and theology there is an exercise named by the Greek word deiknumi. The word simply translated means “occurrence” or “evidence,” but in philosophy it refers to a “thought experiment,” a sort of meditation or exploration of a hypothesis about what might happen if certain facts are true or certain situations experienced. It’s particularly useful if those situations cannot be replicated in a laboratory or if the facts are in the past or future and cannot be presently experienced. St. Paul uses the word only once in his epistles: in the last verse of chapter 12 of the First Letter to the Corinthians, he uses the verbal form when he admonishes his readers to “strive for the greater gifts. And I will show you [deiknuo, ‘I will give you evidence of’] a still more excellent way.” It is the introduction to his famous treatise on agape, divine love, a thought experiment (if you will) about the best expression, the “still more excellent” expression of the greatest of the virtues. God’s response to Abraham’s challenge is to take Abraham outside and show him the stars and ask him, “Has it ever occurred to you that you might be wrong?” Well, God doesn’t, actually . . . but that’s what it boils down to. God’s response to Abraham is, “Thank again!”

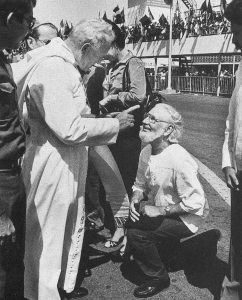

God’s response to Abraham’s challenge is to take Abraham outside and show him the stars and ask him, “Has it ever occurred to you that you might be wrong?” Well, God doesn’t, actually . . . but that’s what it boils down to. God’s response to Abraham is, “Thank again!” When Pope John Paul II scolded Fr. Cardenal upon the his arrival in Nicaragua, it was because Cardenal had collaborated with the Marxist Sandinistas and, after the Sandinista victory in 1979, he became their government’s Minister of Culture. His brother, Fr. Fernando Cardenal S.J. also worked with the Sandinista government in the Ministry of Education, directing a successful literacy campaign. There were a handful of other priests working in the government, as well.

When Pope John Paul II scolded Fr. Cardenal upon the his arrival in Nicaragua, it was because Cardenal had collaborated with the Marxist Sandinistas and, after the Sandinista victory in 1979, he became their government’s Minister of Culture. His brother, Fr. Fernando Cardenal S.J. also worked with the Sandinista government in the Ministry of Education, directing a successful literacy campaign. There were a handful of other priests working in the government, as well.  We know that if there are tribal circles on that foundational paper, they are more like the circles on a Venn diagram, not only touching but overlapping. That was true of the ancient Hebrews; their tribalism might demand ethnic purity, but they never achieved it; the Old Testament demonstrates that, again and again! Modern ideological tribalism is no different. Ideologies, religious beliefs, political opinions differ in many ways, but in many others they share much in common; they overlap. People’s lives and opinions overlap, but ideological tribalism encourages us to hear only the differing opinions and blinds us to our similar lives.

We know that if there are tribal circles on that foundational paper, they are more like the circles on a Venn diagram, not only touching but overlapping. That was true of the ancient Hebrews; their tribalism might demand ethnic purity, but they never achieved it; the Old Testament demonstrates that, again and again! Modern ideological tribalism is no different. Ideologies, religious beliefs, political opinions differ in many ways, but in many others they share much in common; they overlap. People’s lives and opinions overlap, but ideological tribalism encourages us to hear only the differing opinions and blinds us to our similar lives. Some translations of the Bible like to add to it. They insert explanatory headings and titles into the teachings of the authors of scripture or before the parables or important elements in Jesus’ life and teachings. The New International Version, for example, adds the title “The Parable of the Rich Fool” to our gospel text for today. It breaks up our reading from Ecclesiastes with three such headings: “Everything Is Meaningless,” “Wisdom Is Meaningless,” and “Toil Is Meaningless.” If you have a bible like that, take those titles and subheadings with a very large grain of salt because they are simply not accurate!

Some translations of the Bible like to add to it. They insert explanatory headings and titles into the teachings of the authors of scripture or before the parables or important elements in Jesus’ life and teachings. The New International Version, for example, adds the title “The Parable of the Rich Fool” to our gospel text for today. It breaks up our reading from Ecclesiastes with three such headings: “Everything Is Meaningless,” “Wisdom Is Meaningless,” and “Toil Is Meaningless.” If you have a bible like that, take those titles and subheadings with a very large grain of salt because they are simply not accurate!