Melrose, Scotland, is an important place in Celtic church history. It was here that St. Aidan, abbot of Lindisfarne, established a mainland monastery bringing monks from Iona. It was in that Celtic monastery that St. Cuthbert became a monk and entered holy orders. This early monastic foundation, probably 2-1/2 miles from the current monastic ruin, has completely disappeared. In fact, was long gone by the 12th Century when Cistercian monks came and started what eventually became the Melrose Abbey we know now.

Melrose, Scotland, is an important place in Celtic church history. It was here that St. Aidan, abbot of Lindisfarne, established a mainland monastery bringing monks from Iona. It was in that Celtic monastery that St. Cuthbert became a monk and entered holy orders. This early monastic foundation, probably 2-1/2 miles from the current monastic ruin, has completely disappeared. In fact, was long gone by the 12th Century when Cistercian monks came and started what eventually became the Melrose Abbey we know now.

Melrose Abbey, as it exists today, is an excavated ruin of what was a very large foundation of Cistercians; presumably there were hundreds of them. (I’ve tried to find an estimate of their highest numbers and have been unable to do so. However, I have found out that they herded between 13,000 and 15,000 sheep in the 14th Century! That takes a lot of manpower….) Only a few of the walls of the chapel, which we American Episcopalians would consider a very large gothic church, remain standing. Intriguing details of the place include a still-standing bell tower (in most monastic ruins these have long since fallen), a gargoyle in form of a pig playing bagpipes, the alleged burial place of Robert the Bruce’s heart (it really was buried here but whether a mummified heart found buried outside the cloister in an iron box is his is subject to some debate), and the beautiful large tracery window of the south transept (the work of a French mason now, of course, devoid of glass).

But the thing I thought about most as I left the place was the display of waste disposal artifacts. Unearthed in the excavations and on prominent display is the monks’ latrine, the “great drain” which carried away its contents and the waste of the on-site tannery, and a collection of pottery urinals! (Urine, however, was not considered waste! Tanners, which the monks were, soaked animal skins in urine to remove hair fibers. Urine is also used as a mordant to help prepare textiles, especially wool, for dyeing – and remember, these monks were shepherds with thousands of sheep to sheer and, one assumes, produce usable wool. In Scotland, the traditional process of “walking” (stretching) the tweed was preceded by soaking in urine. So these urinals may have been for the collection of a useful and necessary product, not considered waste.)

But the thing I thought about most as I left the place was the display of waste disposal artifacts. Unearthed in the excavations and on prominent display is the monks’ latrine, the “great drain” which carried away its contents and the waste of the on-site tannery, and a collection of pottery urinals! (Urine, however, was not considered waste! Tanners, which the monks were, soaked animal skins in urine to remove hair fibers. Urine is also used as a mordant to help prepare textiles, especially wool, for dyeing – and remember, these monks were shepherds with thousands of sheep to sheer and, one assumes, produce usable wool. In Scotland, the traditional process of “walking” (stretching) the tweed was preceded by soaking in urine. So these urinals may have been for the collection of a useful and necessary product, not considered waste.)

Of course, such workings were necessary; they are in any place where large numbers of people live together. One can see that the original planners of the abbey had taken this into account in the very design and lay out of the buildings. It was typical in these early medieval abbeys to lay out the cloister and conventual buildings on the south side of the abbey church so that they would not be in the shade of the church throughout most of the day; abbeys were not heated and their cloister gardens provided the monks with a good deal of their food, so sunlight was much valued. However, at Melrose the conventual structures are to the north of the chapel because it was on this side that water from the River Tweed could be diverted to the abbey, providing it fresh water and a means of flushing waste away through the “great drain”.

On the north of the abbey grounds is a long, deep, stone-lined rectangular pit. A ground-level green and white sign labels it “Latrine”. About a foot or two of scummy, green, stagnant-looking water stands in it; I wondered if the Historic Scotland folks keep it that way for effect. The sign informs one that it would be periodically flushed out through the “great drain” (I keep putting that in quotes because that is the name given an exposed stone-lined culvert further to the north of the property heading downhill toward the river). One can imagine the long, narrow building sitting atop this pit with out-house privy seats.

On the north of the abbey grounds is a long, deep, stone-lined rectangular pit. A ground-level green and white sign labels it “Latrine”. About a foot or two of scummy, green, stagnant-looking water stands in it; I wondered if the Historic Scotland folks keep it that way for effect. The sign informs one that it would be periodically flushed out through the “great drain” (I keep putting that in quotes because that is the name given an exposed stone-lined culvert further to the north of the property heading downhill toward the river). One can imagine the long, narrow building sitting atop this pit with out-house privy seats.

I made note of the fact that while this “latrine” is fairly far removed from the cloister and the residential “range” of the abbey, it is right next door to what is believed to be the “novices’ day room”. In other words, those not yet fully members of the community had to put up with whatever odor might emanate from the loo; it seems there’s always been a hierarchy or division in the church, those who are in and those who are out, those who are privileged and those who are not, those who get to deal with the crap and those who are above that.

The main drain runs from the latrine (and the tannery) to the northwest toward what’s called the “mill lade”, a diverted stream from the River Tweed. On the other side of the drain is the commendator’s house. Built in the 15th Century, the original purpose of the building is unknown. In the late 16th Century, it was converted to a home for the last commendator of the abbey. It now houses a museum in which bits of stonework, pottery, and other items excavated from or pertinent to the abbey are on display. It is here that one finds a display case on one side of which are pottery pitchers used to serve ale or beer in the refectory; on the other side, urinals used by the monks in their dormitories. The two sorts of vessels are similar, but clearly distinguishable – good thing that!

I think this is first museum display of urinals I’ve ever seen, and the first monastic ruin in which the privy was so prominently signed and explained. So, naturally, that’s what caught my attention and occupied my thoughts as I left Melrose. As I pondered this, I realized that such waste disposal can be a metaphor for salvation – the flushing away of bodily waste and of human activities like tanning representing the washing away of sin through the salvific act of Christ. It’s not a metaphor one hears in many parish sermons (and I don’t feel inclined to use it myself), but it’s certainly a useful one for contemplation.

Traditional Christian teaching, especially that of the Middle Ages in which Melrose Abbey was built and of the Catholic Church reflected of the Gaelic hymns collected in Dantá Dé, focuses on the sacrifice of Jesus on the Cross as that moment which worked the cleansing of human souls, on Good Friday and the shedding of the Holy Blood as that which washes us from sin.

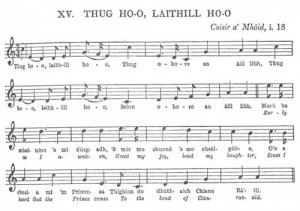

There is also a Good Friday hymn in Dantá Dé described as a “lullaby of the people of Baile-Argáin” and as “ancient music of Ireland” which exemplifies this. Here is the original Gaeilge:

Cuimhnigh a dhuine, gur thrí d’ choirthibh do céasadh Críost

Chun sal an pheacaidh do ghlanadh do phréimhshlioche Aoibh;

Ó dhóire A chuid fola chun sinn-ne go léir do nigh’

Bíom dá shíor-mholadh go h-osnadhach béarach choidhch.’

Ar lár mo chroidhe-se, a Rí ghil na bhflaitheas naomh,

Adhain teine an Naoimh-Sp’raid, mar ‘s caora tá ‘bhfad ar strae mé,

A lasaighfeas m’inntinn chun gníomhartha na n-olc do thréig’,

‘S a chuireas díbirt as mo smaointe ar bhaoise an tsaoghail.

Míle glóir don Athair ghní gach ribe de’n bhféar ag fás,

Míle glóir do’n Mhac ‘ghní gach gráinne de’n ghainimh san tráig,

Míle glóir do’n Spioraid ‘ghní gach réalt a bhflaitheas go h-árd,

Mar do bhi dtúis an tsaoghail, mar bhéas a’s mar tá.

And here is Ní Ógáin’s translation:

Remember, O man, that through thy sins Christ was crucified

To cleanse the stain of sin from the root-stock of Eve;

Since He shed His blood to save us altogether,

Let us be ever praising Him, with sighs and tears.

In the midst of my heart, O fair King of the holy heavens,

Kindle fire of the Holy Spirit, – for I am a sheep that is far astray -,

That will lighten my mind to forsake the deeds of evil,

And banish the folly of the world from out of my thoughts.

A thousand glories to the Father Who makes each blade of the growing grass,

A thousand glories to the Son, Who makes each grain of sand on the shore,

A thousand glories to the Spirit, Who makes each star in the heavens on high,

As it was in the beginning of the world, will be, and [now] is.

It’s a lovely hymn, and I believe its initial focus on Good Friday is correct so far as it goes; after all, as St. Paul wrote, “We proclaim Christ crucified.” (1 Cor. 1:23) However, the truth of the matter is that if his manner of life and his teaching had not preceded it, Jesus’ death on the Cross would have had no meaningful context. If there had been no Resurrection three days later, his death at Calvary would long ago have been forgotten. If Jesus’ death alone accomplished salvation there would have been no need for his rising to new life. The hymn concludes by raising our vision beyond the cross to the glories of creation.

So I would suggest that in a more complete, and surely in a Celtic, understanding, our salvation is worked not simply by Christ’s death but by the whole of what some scholars have called “the Christ event” – his conception, birth, life, teachings, death, resurrection, and ascension – all of those parts of Christ’s life, temporal and eternal, work to our redemption, our justification, our sanctification, and our salvation. I think this rings particularly true in Celtic spirituality; though the ancient hymn focuses on the crucifixion as the cleansing act, it concludes with a doxology praising the Holy Trinity not for that, but for creation of everything from the lowliest grain of sand to the brightest shining star. Consider also this verse from the famous lorica, St. Patrick’s Breastplate, as translated by Cecil Frances Alexander:

I bind this today to me forever

By power of faith, Christ’s incarnation;

His baptism in Jordan river,

His death on Cross for my salvation;

His bursting from the spicèd tomb,

His riding up the heavenly way,

His coming at the day of doom

I bind unto myself today.

We proclaim Christ crucified, Christ risen, Christ ascended; we proclaim Christ who has flushed away our waste!

Melrose, Scotland, is an important place in Celtic church history. It was here that St. Aidan, abbot of Lindisfarne, established a mainland monastery bringing monks from Iona. It was in that Celtic monastery that St. Cuthbert became a monk and entered holy orders. This early monastic foundation, probably 2-1/2 miles from the current monastic ruin, has completely disappeared. In fact, was long gone by the 12th Century when Cistercian monks came and started what eventually became the Melrose Abbey we know now.

Melrose, Scotland, is an important place in Celtic church history. It was here that St. Aidan, abbot of Lindisfarne, established a mainland monastery bringing monks from Iona. It was in that Celtic monastery that St. Cuthbert became a monk and entered holy orders. This early monastic foundation, probably 2-1/2 miles from the current monastic ruin, has completely disappeared. In fact, was long gone by the 12th Century when Cistercian monks came and started what eventually became the Melrose Abbey we know now. But the thing I thought about most as I left the place was the display of waste disposal artifacts. Unearthed in the excavations and on prominent display is the monks’ latrine, the “great drain” which carried away its contents and the waste of the on-site tannery, and a collection of pottery urinals! (Urine, however, was not considered waste! Tanners, which the monks were, soaked animal skins in urine to remove hair fibers. Urine is also used as a mordant to help prepare textiles, especially wool, for dyeing – and remember, these monks were shepherds with thousands of sheep to sheer and, one assumes, produce usable wool. In Scotland, the traditional process of “walking” (stretching) the tweed was preceded by soaking in urine. So these urinals may have been for the collection of a useful and necessary product, not considered waste.)

But the thing I thought about most as I left the place was the display of waste disposal artifacts. Unearthed in the excavations and on prominent display is the monks’ latrine, the “great drain” which carried away its contents and the waste of the on-site tannery, and a collection of pottery urinals! (Urine, however, was not considered waste! Tanners, which the monks were, soaked animal skins in urine to remove hair fibers. Urine is also used as a mordant to help prepare textiles, especially wool, for dyeing – and remember, these monks were shepherds with thousands of sheep to sheer and, one assumes, produce usable wool. In Scotland, the traditional process of “walking” (stretching) the tweed was preceded by soaking in urine. So these urinals may have been for the collection of a useful and necessary product, not considered waste.) On the north of the abbey grounds is a long, deep, stone-lined rectangular pit. A ground-level green and white sign labels it “Latrine”. About a foot or two of scummy, green, stagnant-looking water stands in it; I wondered if the Historic Scotland folks keep it that way for effect. The sign informs one that it would be periodically flushed out through the “great drain” (I keep putting that in quotes because that is the name given an exposed stone-lined culvert further to the north of the property heading downhill toward the river). One can imagine the long, narrow building sitting atop this pit with out-house privy seats.

On the north of the abbey grounds is a long, deep, stone-lined rectangular pit. A ground-level green and white sign labels it “Latrine”. About a foot or two of scummy, green, stagnant-looking water stands in it; I wondered if the Historic Scotland folks keep it that way for effect. The sign informs one that it would be periodically flushed out through the “great drain” (I keep putting that in quotes because that is the name given an exposed stone-lined culvert further to the north of the property heading downhill toward the river). One can imagine the long, narrow building sitting atop this pit with out-house privy seats.  It was a very full day with lots to consider, lots to think about, and lots to relate. So let us return to Clovensford Country Hotel for the moment and consider the “full Scottish breakfast.” The full Irish, it ain’t! At least as served at Clovensford. Don’t get me wrong; it was a lovely breakfast, but it wasn’t what I was expecting.

It was a very full day with lots to consider, lots to think about, and lots to relate. So let us return to Clovensford Country Hotel for the moment and consider the “full Scottish breakfast.” The full Irish, it ain’t! At least as served at Clovensford. Don’t get me wrong; it was a lovely breakfast, but it wasn’t what I was expecting.  Driving on the left side of the road is something that pretty much comes back to you quickly after having done it before. Scottish roads are nearly identical to the Irish, though their country lanes are wider. I made a fool of myself getting into a place in the rental yard where I had to back up and couldn’t figure out for several minutes how to get the darned thing into reverse, but eventually figured that out.

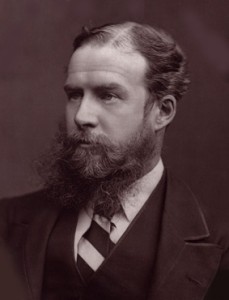

Driving on the left side of the road is something that pretty much comes back to you quickly after having done it before. Scottish roads are nearly identical to the Irish, though their country lanes are wider. I made a fool of myself getting into a place in the rental yard where I had to back up and couldn’t figure out for several minutes how to get the darned thing into reverse, but eventually figured that out.  I had no idea who John Lubbock was, although I now know that I certainly should have. He was a Victoria era banker with many side interests, and the First Baron Avebury. He also was a good friend of Charles Darwin, whose hometown of Shrewsbury, Shropshire, I will be visiting in just under two weeks.

I had no idea who John Lubbock was, although I now know that I certainly should have. He was a Victoria era banker with many side interests, and the First Baron Avebury. He also was a good friend of Charles Darwin, whose hometown of Shrewsbury, Shropshire, I will be visiting in just under two weeks.