From the Book of Acts:

“How is it that we hear, each of us, in our own native language? Parthians, Medes, Elamites, and residents of Mesopotamia, Judea and Cappadocia, Pontus and Asia, Phrygia and Pamphylia, Egypt and the parts of Libya belonging to Cyrene, and visitors from Rome, both Jews and proselytes, Cretans and Arabs – in our own languages we hear them speaking about God’s deeds of power.”

(From the Daily Office Lectionary – Acts 2:8-11 – August 3, 2012)

These are the words spoken by the great crowd of Jews and others who thronged the streets of Jerusalem for the Festival of Shavu’ot when the Twelve, empowered by the Holy Spirit, begin to tell the story of Jesus in languages they had never before spoken. Shavu’ot is a celebration with both agricultural and historical significance in Judaism. It is known as the “festival of the first fruits,” a harvest feast when the first fruits were brought as offerings to the Temple; it is also known as the “festival of the giving of the Law,” a celebration of the handing down of Torah on Mt. Sinai. It was called Pentecost, a Greek word meaning “fiftieth”, because it always falls on the fiftieth day after the Passover. That year it fell on the fiftieth day after the Resurrection and, thus, the Christian feast of the Holy Spirit carries that name, as well.

These are the words spoken by the great crowd of Jews and others who thronged the streets of Jerusalem for the Festival of Shavu’ot when the Twelve, empowered by the Holy Spirit, begin to tell the story of Jesus in languages they had never before spoken. Shavu’ot is a celebration with both agricultural and historical significance in Judaism. It is known as the “festival of the first fruits,” a harvest feast when the first fruits were brought as offerings to the Temple; it is also known as the “festival of the giving of the Law,” a celebration of the handing down of Torah on Mt. Sinai. It was called Pentecost, a Greek word meaning “fiftieth”, because it always falls on the fiftieth day after the Passover. That year it fell on the fiftieth day after the Resurrection and, thus, the Christian feast of the Holy Spirit carries that name, as well.

Twenty centuries later, the Jews still celebrate Shavu’ot and Christians still celebrate Pentecost, but what a different world we inhabit. Can we still find meaning in the notion of offering the first fruits to God? Does the giving the Law still have significance? And what of all those languages and the Apostles’ unprecedented immediate linguistic skill?

For us North American Christians an agricultural feast seems a distant and remote idyllic pastoral fantasy. We are no longer connected to the land. Our culture has moved away from an agrarian basis, through the industrial revolution, even beyond a manufacturing basis; we now live in what is being called a “service economy”. We no longer generally produce anything tangible! What are the “first fruits” of non-productive labor in a service economy? It just boils down to money, I guess.

And what about the myth (a word I use with no disrespect intended and with no suggestion that the story’s point is untrue) of God giving the stone tablets to Moses? In a time when that Law has been largely set aside by Christians and even many Jews – in a time when most people have separated the secular civil laws of everyday life from religious observance and custom – in a time when we conceive of the law as something made (“like sausage”) by a group of bickering, nasty, polarized, do-nothing elected officials – in such a time, how are we to give thanks for “the law”? Do we even want to?

Which leaves me to ponder that gift of languages? There are still plenty of them and there are more, in a sense, than ever before; even as actual, spoken tongues die out for lack of use, new means of communication arise – emoticons and email abbreviations have birthed tweets and hashtags – Facebook and LinkedIn and their ilk are the new “crowded streets” – night-time Twitter conversations are held by church people discussing ways “social media” can be used to spread the Gospel – tongues of flame seem to dance on computer monitors and laptops, on tablets and smartphones.

How is it we hear? How is it we understand? How is it we grasp the ancient truths of receiving the Law, the offering the first fruits, experiencing God’s deed of power? I’ve no doubt that hearing and understanding and comprehension are going on . . . but I often wonder if the church (the institution, not the people) is playing any part in that process of communication and comprehension. I hope and pray the Holy Spirit will alight upon us all and give us the gifts we need to do so, so that all may hear and understand in whatever “language” they best comprehend.

====================

Father Funston is the rector of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Medina, Ohio.

This past Sunday, the Episcopal Church marked the 28th anniversary of the women known as “the Philadelphia Eleven” who were ordained on July 29, 1974. Four retired bishops (Daniel Corrigan, Robert DeWitt, Edward Welles and George Barrett) chose to defy the General Convention of the Episcopal Church which, at its regular triennial meeting in 1973, had voted against opening the priesthood to women; women were already eligible for ordination as deacons. Joined by male presbyters who supported them and the candidates, they ordained eleven women deacons to the priesthood: Merrill Bittner, Alla Bozarth-Campbell, Alison Cheek, Emily Hewitt, Carter Heyward, Suzanne Hiatt, Marie Moorefield Fleisher, Jeannette Piccard, Betty Bone Schiess, Katrina Martha Swanson, and Nancy Hatch Wittig. Shortly thereafter, four additional women were also “irregularly” ordained: Eleanor Lee McGee, Alison Palmer, Betty Powell, and Diane Tickell. A firestorm of controversy erupted in the church: charges were filed against these dissident bishops (Daniel Corrigan, Robert DeWitt, Edward Welles and George Barrett) and an emergency meeting of the Episcopal House of Bishops was convened on August 15, 1974.

This past Sunday, the Episcopal Church marked the 28th anniversary of the women known as “the Philadelphia Eleven” who were ordained on July 29, 1974. Four retired bishops (Daniel Corrigan, Robert DeWitt, Edward Welles and George Barrett) chose to defy the General Convention of the Episcopal Church which, at its regular triennial meeting in 1973, had voted against opening the priesthood to women; women were already eligible for ordination as deacons. Joined by male presbyters who supported them and the candidates, they ordained eleven women deacons to the priesthood: Merrill Bittner, Alla Bozarth-Campbell, Alison Cheek, Emily Hewitt, Carter Heyward, Suzanne Hiatt, Marie Moorefield Fleisher, Jeannette Piccard, Betty Bone Schiess, Katrina Martha Swanson, and Nancy Hatch Wittig. Shortly thereafter, four additional women were also “irregularly” ordained: Eleanor Lee McGee, Alison Palmer, Betty Powell, and Diane Tickell. A firestorm of controversy erupted in the church: charges were filed against these dissident bishops (Daniel Corrigan, Robert DeWitt, Edward Welles and George Barrett) and an emergency meeting of the Episcopal House of Bishops was convened on August 15, 1974. These women were not the first to be ordained to the Anglican priesthood, however. During the Second World War, Florence Li Tim-Oi was ordained to the presbyterate on January 25, 1944, by the Rt. Rev. Ronald Hall, Bishop of Hong Kong, in response to the crisis among Anglican Christians in China caused by the Japanese invasion. No male clergy could be found who were willing to take on the onerous ministry, but Ms. Li was, so she was ordained and served with distinction. After the war, the Archbishop of Canterbury sought to make the bishop and the priest rescind the ordination, but neither did. Ms. Li voluntarily ceased serving as a priest until more than 30 years later when she immigrated to Canada where the Anglican Church, following the Episcopal Church’s lead, had begun to ordain women. Her priesthood was recognized and she served as an honorary canon in Toronto, ministering among the immigrant Chinese population.

These women were not the first to be ordained to the Anglican priesthood, however. During the Second World War, Florence Li Tim-Oi was ordained to the presbyterate on January 25, 1944, by the Rt. Rev. Ronald Hall, Bishop of Hong Kong, in response to the crisis among Anglican Christians in China caused by the Japanese invasion. No male clergy could be found who were willing to take on the onerous ministry, but Ms. Li was, so she was ordained and served with distinction. After the war, the Archbishop of Canterbury sought to make the bishop and the priest rescind the ordination, but neither did. Ms. Li voluntarily ceased serving as a priest until more than 30 years later when she immigrated to Canada where the Anglican Church, following the Episcopal Church’s lead, had begun to ordain women. Her priesthood was recognized and she served as an honorary canon in Toronto, ministering among the immigrant Chinese population. Have you ever done that thing on a public street corner where a couple of people stand there looking up and pretty soon some passing pedestrian, wondering what they are gazing at, will stop and look up, and then another and then another and so on until a lot of people are looking up into the sky at nothing for no reason? I have an image of that in my mind when I read the this passage, although in this case the “men of Galilee” are not looking at nothing for no reason. They are looking at something they can no longer see, except in their minds’ eye, and it is certainly not “for no reason” that they are doing so. Something phenomenal has happened to them; someone they thought had been killed by the authorities had returned from the dead, had eaten with them, talked with them, appeared to them over the course of over seven weeks, and now he had “ascended into heaven.” They had plenty of reason to stand there staring into the sky into which he had apparently gone.

Have you ever done that thing on a public street corner where a couple of people stand there looking up and pretty soon some passing pedestrian, wondering what they are gazing at, will stop and look up, and then another and then another and so on until a lot of people are looking up into the sky at nothing for no reason? I have an image of that in my mind when I read the this passage, although in this case the “men of Galilee” are not looking at nothing for no reason. They are looking at something they can no longer see, except in their minds’ eye, and it is certainly not “for no reason” that they are doing so. Something phenomenal has happened to them; someone they thought had been killed by the authorities had returned from the dead, had eaten with them, talked with them, appeared to them over the course of over seven weeks, and now he had “ascended into heaven.” They had plenty of reason to stand there staring into the sky into which he had apparently gone.

As the letter to the Romans draws to a close, Paul sends greetings to several persons by name: Phoebe (named here), Prisca, Aquila, Epaenetus, Mary, Andronicus, Junia, and many others. As I read through there names, I cannot help but wonder who these otherwise forgotten church members were. What were their roles in the church? What did they do outside the church?

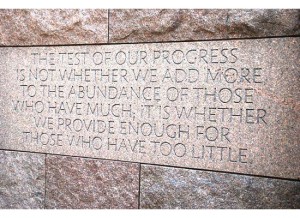

As the letter to the Romans draws to a close, Paul sends greetings to several persons by name: Phoebe (named here), Prisca, Aquila, Epaenetus, Mary, Andronicus, Junia, and many others. As I read through there names, I cannot help but wonder who these otherwise forgotten church members were. What were their roles in the church? What did they do outside the church? In yesterday’s gospel lesson Jesus told the story of the king separating the righteous form wicked as a shepherd separates sheep from goats and saying “As you care for the poor, you care for me.” It reminded me of a few cogent remarks that have been made about the measure of society – From Samuel Johnson: “A decent provision for the poor is the true test of civilization.” From Mahatma Ghandi: “A nation’s greatness is measured by how it treats its weakest members.” From Franklin Delano Roosevelt: “The test of our progress is not whether we add more to the abundance of those who have much, it is whether we provide for those who have too little.”

In yesterday’s gospel lesson Jesus told the story of the king separating the righteous form wicked as a shepherd separates sheep from goats and saying “As you care for the poor, you care for me.” It reminded me of a few cogent remarks that have been made about the measure of society – From Samuel Johnson: “A decent provision for the poor is the true test of civilization.” From Mahatma Ghandi: “A nation’s greatness is measured by how it treats its weakest members.” From Franklin Delano Roosevelt: “The test of our progress is not whether we add more to the abundance of those who have much, it is whether we provide for those who have too little.” More than any other story in all of the gospel accounts, this one underscores for me what is at the heart of the Good News of Jesus Christ: love of neighbor, service to others, care for those who are unable to care for themselves, and in so doing to demonstrate our love of God.

More than any other story in all of the gospel accounts, this one underscores for me what is at the heart of the Good News of Jesus Christ: love of neighbor, service to others, care for those who are unable to care for themselves, and in so doing to demonstrate our love of God.  You know this story. A rich man goes away for some period of time entrusting huge amounts of wealth to his servants. To one he gives five talents, an amount of silver roughly the value of one hundred years of work of an ordinary laborer. To another two and to the third one. The first two use the money and double it. The third, timid and fearful of his employer’s reprisal should he lose it, buries it in the ground. Upon the owner’s return, he is punished for failing to invest the money.

You know this story. A rich man goes away for some period of time entrusting huge amounts of wealth to his servants. To one he gives five talents, an amount of silver roughly the value of one hundred years of work of an ordinary laborer. To another two and to the third one. The first two use the money and double it. The third, timid and fearful of his employer’s reprisal should he lose it, buries it in the ground. Upon the owner’s return, he is punished for failing to invest the money. This is one of the things that I find so captivating about the Old Testament: its heroes and heroines are not supermen and superwomen. They aren’t even regular, run-of-the-mill folks. They are often, as here, the outcasts and sinners, the morally flawed, the ethically ambiguous, the folks who were looking out for themselves as much as they were trying to do something good (sometimes a lot more the former than the latter). “A prostitute whose name was Rahab” was as capable of doing God’s work as was a Levite, a priest, or a great military leader.

This is one of the things that I find so captivating about the Old Testament: its heroes and heroines are not supermen and superwomen. They aren’t even regular, run-of-the-mill folks. They are often, as here, the outcasts and sinners, the morally flawed, the ethically ambiguous, the folks who were looking out for themselves as much as they were trying to do something good (sometimes a lot more the former than the latter). “A prostitute whose name was Rahab” was as capable of doing God’s work as was a Levite, a priest, or a great military leader.  The 77th General Convention of the Episcopal Church has just concluded and, I know from having been a deputy or a volunteer at past conventions, those who attended had a wonderful time (unless they came away righteously angry over one action or another, in which case they are now thoroughly enjoying being in the “right” while the rest of the church, they are sure, is going to Hell in a hand-basket). But I do wonder whether the actions of #GC77 (as the Twitter hashtag named it) will “drop like the rain” and “condense the like dew” and provide gentle nurture for “new growth.”

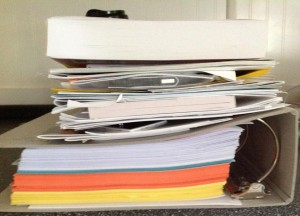

The 77th General Convention of the Episcopal Church has just concluded and, I know from having been a deputy or a volunteer at past conventions, those who attended had a wonderful time (unless they came away righteously angry over one action or another, in which case they are now thoroughly enjoying being in the “right” while the rest of the church, they are sure, is going to Hell in a hand-basket). But I do wonder whether the actions of #GC77 (as the Twitter hashtag named it) will “drop like the rain” and “condense the like dew” and provide gentle nurture for “new growth.”  This overload of unproductive work is not a “gentle rain” . . . this is a Category-5 hurricane, a tsunami, a deluge of biblical proportions! Actually, the thought did occur to me that it’s bigger than “biblical proportions” – the Law of Moses, the Torah, the Pentateuch, the first five books of Holy Scripture, the word of God to the Chosen People for all time (whatever one calls it) in my Oxford Annotated Bible only takes up 308 pages (complete with footnotes). The word of GC77 to the people of the Episcopal Church for a mere three years is more than twice the size, not including the loose-leaf supplement!

This overload of unproductive work is not a “gentle rain” . . . this is a Category-5 hurricane, a tsunami, a deluge of biblical proportions! Actually, the thought did occur to me that it’s bigger than “biblical proportions” – the Law of Moses, the Torah, the Pentateuch, the first five books of Holy Scripture, the word of God to the Chosen People for all time (whatever one calls it) in my Oxford Annotated Bible only takes up 308 pages (complete with footnotes). The word of GC77 to the people of the Episcopal Church for a mere three years is more than twice the size, not including the loose-leaf supplement!