St. Paul wrote….

Were you a slave when called? Do not be concerned about it. Even if you can gain your freedom, make use of your present condition now more than ever. For whoever was called in the Lord as a slave is a freed person belonging to the Lord, just as whoever was free when called is a slave of Christ. You were bought with a price; do not become slaves of human masters. In whatever condition you were called, brothers and sisters, there remain with God. (From the Daily Office Readings, Mar. 10, 2012, 1 Cor. 7:21-24)

This is a troubling text. Paul seems to be telling slaves to remain in their slavery, not to be concerned about their condition of servitude; this would say to others that they should not struggle for the liberation of slaves. Of course, Paul believed the end of this world was right around the corner and such earthly conditions as slavery or mastership would be abolished in his lifetime. He was wrong … so how does his text speak to us today? ~ Paul’s counsel to remain “in whatever condition you were called” should not be used as a justification for not seeking better circumstances for oneself and an improvement of one’s circumstances. Indeed, it is debatable that Paul even gave that advice to stay in one’s “condition” or “situation”. It is rather more probable, it seems to me, that his counsel is to remain steadfast in one’s conversion (Greek kalesis = calling) to Christian faith and brotherhood resisting the pressures of one’s prior status – slave or master, Jew or Greek, married or single, whatever that condition or status may be – and this might even mean a change in that circumstance. I am so persuaded by the arguments of S. Scott Bartchy, Professor of Christian Origins and the History of Religion, Department of History, UCLA. He has examined how the Greek word kalesis meaning “calling”, “invitation” or “summons” – correctly translated as vocatione by St. Jerome in the Vulgate and as “calling” (or “called”) in the Authorized Version – came to be translated in later English versions as “condition”. His surprising (and probably correct) conclusion is to blame Martin Luther and the influence of his German translation! Bartchy has argued that it is certain that Paul did not teach enslaved Christ-followers to “stay in slavery.” Rather, he exhorted them (and us) to “remain in the calling in Christ by which you were called.” Quite the opposite of a passive quietism accepting of unjust social institutions, Paul’s exhortation is to an active faith repenting our own “blindness to human need and suffering and our indifference to injustice and cruelty.” (From the American BCP’s Ash Wednesday Litany of Penitence, p. 268)

This is a troubling text. Paul seems to be telling slaves to remain in their slavery, not to be concerned about their condition of servitude; this would say to others that they should not struggle for the liberation of slaves. Of course, Paul believed the end of this world was right around the corner and such earthly conditions as slavery or mastership would be abolished in his lifetime. He was wrong … so how does his text speak to us today? ~ Paul’s counsel to remain “in whatever condition you were called” should not be used as a justification for not seeking better circumstances for oneself and an improvement of one’s circumstances. Indeed, it is debatable that Paul even gave that advice to stay in one’s “condition” or “situation”. It is rather more probable, it seems to me, that his counsel is to remain steadfast in one’s conversion (Greek kalesis = calling) to Christian faith and brotherhood resisting the pressures of one’s prior status – slave or master, Jew or Greek, married or single, whatever that condition or status may be – and this might even mean a change in that circumstance. I am so persuaded by the arguments of S. Scott Bartchy, Professor of Christian Origins and the History of Religion, Department of History, UCLA. He has examined how the Greek word kalesis meaning “calling”, “invitation” or “summons” – correctly translated as vocatione by St. Jerome in the Vulgate and as “calling” (or “called”) in the Authorized Version – came to be translated in later English versions as “condition”. His surprising (and probably correct) conclusion is to blame Martin Luther and the influence of his German translation! Bartchy has argued that it is certain that Paul did not teach enslaved Christ-followers to “stay in slavery.” Rather, he exhorted them (and us) to “remain in the calling in Christ by which you were called.” Quite the opposite of a passive quietism accepting of unjust social institutions, Paul’s exhortation is to an active faith repenting our own “blindness to human need and suffering and our indifference to injustice and cruelty.” (From the American BCP’s Ash Wednesday Litany of Penitence, p. 268)

Psalm 73 begins with a confession of green-eyed envy; the Psalmist acknowledges that he slipped and nearly stumbled away from faith because of his envy of the prosperous who “suffer no pain” and whose “bodies are sleek and sound.” This psalm brings in to sharp focus a complex and perplexing problems for persons of faith: the prosperity of the wicked and the suffering of the righteous. The Psalmist saw that “the wicked, always at ease, increase their wealth;” the wicked seem to be totally self-reliant and autonomous people. They seem not to need God; they are able to take care of themselves. It bothered the Psalmist that their lifestyle apparently works! Thus, he concluded that the attempt to lead a moral life is absolutely pointless; he despaired that it was in vain that he kept his heart clean and “washed my hands in innocence.” However, upon entering the temple he came to understand that the wicked wealthy will “come to destruction, come to an end, and perish from terror!” And so he comes to sing of his reliance on God, his strength and his portion for ever. At the end of the psalm, he vows to “speak of all God’s works in the gates of the city of Zion.” ~ In our society with such a deep division between rich and poor, between “the 1%” and the middle class, this psalm’s cries of envy and despair, I’m sure, speak to many, but I hope its reliance on the God of eternity, the God of hope speaks louder. “Whom have I in heaven but you? And having you I desire nothing upon earth.” The Psalmist, entering the sanctuary and changing his point of view from the worldly to the eternal, was led to see that no matter how things looked here in the temporal world his trust and confidence in God was the greatest gift of God’s grace, greater than any earthly wealth he could contemplate. A change of perspective, so that one views life through the lens of eternity, brings clarity of vision, both of the world around us and of our call to ministry in this world. It does not permit us to become embittered with green-eyed envy nor to sink into despair, but neither does it encourage us to accept wealth inequality and injustice with a promise of “pie in the sky by-and-by.” Rather, it admonishes us to “speak of all God’s works in the gates of the city.” And as St. Thomas Aquinas reminds us, “Mercy and truth are necessarily found in all God’s works” and “justice must exist in all God’s works.” (Summa Theologica, Question 21, Article 4) Psalm 73 in the Daily Office Lectionary during Lent echoes the exhortation of the Prophet Micah: “He has told you, O mortal, what is good; and what does the Lord require of you but to do justice, and to love kindness, and to walk humbly with your God?” (Micah 6:8)

Psalm 73 begins with a confession of green-eyed envy; the Psalmist acknowledges that he slipped and nearly stumbled away from faith because of his envy of the prosperous who “suffer no pain” and whose “bodies are sleek and sound.” This psalm brings in to sharp focus a complex and perplexing problems for persons of faith: the prosperity of the wicked and the suffering of the righteous. The Psalmist saw that “the wicked, always at ease, increase their wealth;” the wicked seem to be totally self-reliant and autonomous people. They seem not to need God; they are able to take care of themselves. It bothered the Psalmist that their lifestyle apparently works! Thus, he concluded that the attempt to lead a moral life is absolutely pointless; he despaired that it was in vain that he kept his heart clean and “washed my hands in innocence.” However, upon entering the temple he came to understand that the wicked wealthy will “come to destruction, come to an end, and perish from terror!” And so he comes to sing of his reliance on God, his strength and his portion for ever. At the end of the psalm, he vows to “speak of all God’s works in the gates of the city of Zion.” ~ In our society with such a deep division between rich and poor, between “the 1%” and the middle class, this psalm’s cries of envy and despair, I’m sure, speak to many, but I hope its reliance on the God of eternity, the God of hope speaks louder. “Whom have I in heaven but you? And having you I desire nothing upon earth.” The Psalmist, entering the sanctuary and changing his point of view from the worldly to the eternal, was led to see that no matter how things looked here in the temporal world his trust and confidence in God was the greatest gift of God’s grace, greater than any earthly wealth he could contemplate. A change of perspective, so that one views life through the lens of eternity, brings clarity of vision, both of the world around us and of our call to ministry in this world. It does not permit us to become embittered with green-eyed envy nor to sink into despair, but neither does it encourage us to accept wealth inequality and injustice with a promise of “pie in the sky by-and-by.” Rather, it admonishes us to “speak of all God’s works in the gates of the city.” And as St. Thomas Aquinas reminds us, “Mercy and truth are necessarily found in all God’s works” and “justice must exist in all God’s works.” (Summa Theologica, Question 21, Article 4) Psalm 73 in the Daily Office Lectionary during Lent echoes the exhortation of the Prophet Micah: “He has told you, O mortal, what is good; and what does the Lord require of you but to do justice, and to love kindness, and to walk humbly with your God?” (Micah 6:8) When I think about religion and trees, I remember that Evelyn Underhill, writing not about this parable but about St. Paul’s prayer in the Letter to the Ephesians that the church might be “rooted and grounded in love” (Eph. 3:17), wrote: “By contemplative prayer, I do not mean any abnormal sort of activity or experience, still less a deliberate and artificial passivity. I just mean the sort of prayer that aims at God in and for Himself and not for any of His gifts whatever, and more and more profoundly rests in Him alone: what St. Paul, that vivid realist, meant by being rooted and grounded. When I read those words, I always think of a forest tree. First of the bright and changeful tuft that shows itself to the world and produces the immense spread of boughs and branches, the succession and abundance of leaves and fruits. Then of the vast unseen system of roots, perhaps greater than the branches in strength and extent, with their tenacious attachments, their fan-like system of delicate filaments and their power of silently absorbing food. On that profound and secret life the whole growth and stability of the tree depend. It is rooted and grounded in a hidden world.” (Quoted in Radiance: A Spiritual Memoir of Evelyn Underhill, Bernard Bangley, ed. [Brewster, MA: Paraclete Press, 2004]). We see the tree, its trunk, its branches, its leaves; below in the soil, however, there is a huge unseen network of roots. Love and prayer are the earth which nourishes these roots. Referring Ms. Underhill’s metaphor to Jesus’ parable of the mustard seed, and understanding (as one interpretation of the image) the “kingdom of God” analogized to the tree which grows from it to be the church, we are left with the unmistakeable inference that it is our prayer life which provides the fruitful ground in which the church must grow. I am reminded of a story told by Martha Grace Reese in her book Unbinding the Gospel (Atlanta, GA: Chalice Press, 2008) that when she was consulted by a church growth committee and asked what they should do, she told them to do nothing but pray for at least three months. And I remember another church leader saying, “This year’s level of church growth cannot be sustained on last year’s level of prayer.” Active, sustained, community-wide prayer is an absolute necessity for the church to grow into the abundant, live-giving place where “the birds of the air can make nests in its shade.” The parable challenges us with the idea that God created the church (us) for the birds (those who are not us). Are our churches, through our love and prayers, places where the birds (the ones who are not us, may not be at all like us) can come and abide? Let us pray that they are.

When I think about religion and trees, I remember that Evelyn Underhill, writing not about this parable but about St. Paul’s prayer in the Letter to the Ephesians that the church might be “rooted and grounded in love” (Eph. 3:17), wrote: “By contemplative prayer, I do not mean any abnormal sort of activity or experience, still less a deliberate and artificial passivity. I just mean the sort of prayer that aims at God in and for Himself and not for any of His gifts whatever, and more and more profoundly rests in Him alone: what St. Paul, that vivid realist, meant by being rooted and grounded. When I read those words, I always think of a forest tree. First of the bright and changeful tuft that shows itself to the world and produces the immense spread of boughs and branches, the succession and abundance of leaves and fruits. Then of the vast unseen system of roots, perhaps greater than the branches in strength and extent, with their tenacious attachments, their fan-like system of delicate filaments and their power of silently absorbing food. On that profound and secret life the whole growth and stability of the tree depend. It is rooted and grounded in a hidden world.” (Quoted in Radiance: A Spiritual Memoir of Evelyn Underhill, Bernard Bangley, ed. [Brewster, MA: Paraclete Press, 2004]). We see the tree, its trunk, its branches, its leaves; below in the soil, however, there is a huge unseen network of roots. Love and prayer are the earth which nourishes these roots. Referring Ms. Underhill’s metaphor to Jesus’ parable of the mustard seed, and understanding (as one interpretation of the image) the “kingdom of God” analogized to the tree which grows from it to be the church, we are left with the unmistakeable inference that it is our prayer life which provides the fruitful ground in which the church must grow. I am reminded of a story told by Martha Grace Reese in her book Unbinding the Gospel (Atlanta, GA: Chalice Press, 2008) that when she was consulted by a church growth committee and asked what they should do, she told them to do nothing but pray for at least three months. And I remember another church leader saying, “This year’s level of church growth cannot be sustained on last year’s level of prayer.” Active, sustained, community-wide prayer is an absolute necessity for the church to grow into the abundant, live-giving place where “the birds of the air can make nests in its shade.” The parable challenges us with the idea that God created the church (us) for the birds (those who are not us). Are our churches, through our love and prayers, places where the birds (the ones who are not us, may not be at all like us) can come and abide? Let us pray that they are. Priests and preachers are sowers of the seeds of the gospel, but we are called to do more than simply cast the seed on the ground. Many of us are called to the additional tasks of clearing rocks, tilling the soil, watering and fertilizing, fencing the field, pulling weeds, chasing away pests, and so forth. Paul wrote to the Corinthians, “I planted, Apollos watered, but God gave the growth. You [the church or the unchurched in the mission field] are God’s field.” (1 Cor. 3:6,9) He might have carried the analogy further (as I have done). The analogy breaks down, of course, because weed-choked soil cannot relieve itself of weeds nor can rocky soil relieve itself of stones, but human beings influenced by “the cares of the world, and the lure of wealth, and the desire for other things” can turn from these things. The Lenten “fast” is a time and a mechanism whereby we may make the conscious effort to do so.

Priests and preachers are sowers of the seeds of the gospel, but we are called to do more than simply cast the seed on the ground. Many of us are called to the additional tasks of clearing rocks, tilling the soil, watering and fertilizing, fencing the field, pulling weeds, chasing away pests, and so forth. Paul wrote to the Corinthians, “I planted, Apollos watered, but God gave the growth. You [the church or the unchurched in the mission field] are God’s field.” (1 Cor. 3:6,9) He might have carried the analogy further (as I have done). The analogy breaks down, of course, because weed-choked soil cannot relieve itself of weeds nor can rocky soil relieve itself of stones, but human beings influenced by “the cares of the world, and the lure of wealth, and the desire for other things” can turn from these things. The Lenten “fast” is a time and a mechanism whereby we may make the conscious effort to do so. Only a little bit of yeast is necessary to leaven a whole batch of dough. In ancient Judaism, leaven could not be offered on the altar: “No grain offering that you bring to the Lord shall be made with leaven, for you must not turn any leaven or honey into smoke as an offering by fire to the Lord.” (Leviticus 2:11) Although this prohibition is repeated elsewhere, the Hebrew Scriptures not say why leaven is forbidden. A popular theory is that it is because leaven spoils and corrupts. The Babylonian Talmud uses the image of “yeast in the dough” as a metaphor for “the evil impulse, which causes a ferment in the heart”; the commentary in the Anchor Bible refers to leaven as “the arch-symbol of fermentation, deterioration, and death and, hence, taboo on the altar of blessing and life.” St. Paul, steeped as he was in Jewish learning, used leaven as a metaphor for sin and its insidious ability to infect an entire community such as a church congregation. No amount of sin may be safely tolerated in the community of faith for sin spreads. So our Lenten discipline of self-examination must include an evaluation of our church communities and, says Paul, if we find any among us who is “sexually immoral or greedy, or is an idolater, reviler, drunkard, or robber” we are to “drive out the wicked person from among [us].” These are harsh words that Paul quotes from several places in the Book of Deuteronomy, e.g., Deuteronomy 17:7; 19:19; 21:21. We should temper his admonition with the encouragement of Christ in Matthew’s Gospel: “If another member of the church sins against you, go and point out the fault when the two of you are alone. If the member listens to you, you have regained that one. But if you are not listened to, take one or two others along with you, so that every word may be confirmed by the evidence of two or three witnesses. If the member refuses to listen to them, tell it to the church; and if the offender refuses to listen even to the church, let such a one be to you as a Gentile and a tax collector.” (Matt. 18:15-17) Correction is always preferable to expulsion! As the Ash Wednesday absolution in The Book of Common Prayer reminds us, God’s preference is that sinners “turn from their wickedness and live.” During this Lent, clean out the old leaven of malice and evil, and encourage one another to keep in mind “the need which all Christians continually have to renew their repentance and faith.”

Only a little bit of yeast is necessary to leaven a whole batch of dough. In ancient Judaism, leaven could not be offered on the altar: “No grain offering that you bring to the Lord shall be made with leaven, for you must not turn any leaven or honey into smoke as an offering by fire to the Lord.” (Leviticus 2:11) Although this prohibition is repeated elsewhere, the Hebrew Scriptures not say why leaven is forbidden. A popular theory is that it is because leaven spoils and corrupts. The Babylonian Talmud uses the image of “yeast in the dough” as a metaphor for “the evil impulse, which causes a ferment in the heart”; the commentary in the Anchor Bible refers to leaven as “the arch-symbol of fermentation, deterioration, and death and, hence, taboo on the altar of blessing and life.” St. Paul, steeped as he was in Jewish learning, used leaven as a metaphor for sin and its insidious ability to infect an entire community such as a church congregation. No amount of sin may be safely tolerated in the community of faith for sin spreads. So our Lenten discipline of self-examination must include an evaluation of our church communities and, says Paul, if we find any among us who is “sexually immoral or greedy, or is an idolater, reviler, drunkard, or robber” we are to “drive out the wicked person from among [us].” These are harsh words that Paul quotes from several places in the Book of Deuteronomy, e.g., Deuteronomy 17:7; 19:19; 21:21. We should temper his admonition with the encouragement of Christ in Matthew’s Gospel: “If another member of the church sins against you, go and point out the fault when the two of you are alone. If the member listens to you, you have regained that one. But if you are not listened to, take one or two others along with you, so that every word may be confirmed by the evidence of two or three witnesses. If the member refuses to listen to them, tell it to the church; and if the offender refuses to listen even to the church, let such a one be to you as a Gentile and a tax collector.” (Matt. 18:15-17) Correction is always preferable to expulsion! As the Ash Wednesday absolution in The Book of Common Prayer reminds us, God’s preference is that sinners “turn from their wickedness and live.” During this Lent, clean out the old leaven of malice and evil, and encourage one another to keep in mind “the need which all Christians continually have to renew their repentance and faith.” In this bit from his First Letter to the Church in Corinth, St. Paul nails the Corinthians with sarcasm. Apparently they had been bickering among themselves about who was the most spiritually advanced and some had even boasted that they had grown beyond their teachers, Paul and Apollos. So Paul sardonically congratulates them that they have already achieved every spiritual goal and climbed every spiritual mountain. Paul cynically suggests that he wishes to ride their coattails into glory without the painful cost of obedience that mere mortals must pay. I admire Paul’s willingness to be confrontational with this congregation, but I often find myself unable to do so in my own ministry setting – and I would suspect that I am not alone among clergy. Influenced as we are by our society’s consumer mentality it is all too easy to analyze and evaluate our ministries according to some standard of marketability, but a priest must never forget that popularity with a parish is not proof God’s favor and blessing; clergy are accountable to God not to some corporate-culture inspired performance evaluation. We must struggle not to substitute human approval for obedience to God. In the end, this is true of everyone, not just of clergy. During these weeks in which we are invited “to the observance of a holy Lent, by self-examination and repentance,” it is well to ask who it is we are trying to please, the world around us or God?

In this bit from his First Letter to the Church in Corinth, St. Paul nails the Corinthians with sarcasm. Apparently they had been bickering among themselves about who was the most spiritually advanced and some had even boasted that they had grown beyond their teachers, Paul and Apollos. So Paul sardonically congratulates them that they have already achieved every spiritual goal and climbed every spiritual mountain. Paul cynically suggests that he wishes to ride their coattails into glory without the painful cost of obedience that mere mortals must pay. I admire Paul’s willingness to be confrontational with this congregation, but I often find myself unable to do so in my own ministry setting – and I would suspect that I am not alone among clergy. Influenced as we are by our society’s consumer mentality it is all too easy to analyze and evaluate our ministries according to some standard of marketability, but a priest must never forget that popularity with a parish is not proof God’s favor and blessing; clergy are accountable to God not to some corporate-culture inspired performance evaluation. We must struggle not to substitute human approval for obedience to God. In the end, this is true of everyone, not just of clergy. During these weeks in which we are invited “to the observance of a holy Lent, by self-examination and repentance,” it is well to ask who it is we are trying to please, the world around us or God? This is one of my favorite bits of theology from St. Paul! This portion of the Letter to the Romans is also in the Epistle Lesson for the Great Vigil of Easter in the Episcopal Church’s lectionary. I love the certitude with which Paul writes: “We will certainly by united with him!” For Paul this is incontrovertible! The Greek word translated “certainly” is alla which has the additional meaning of “nevertheless” or “notwithstanding” – in other words, there is nothing that can stand in the way of our resurrection with Christ. I am reminded of another favorite passage from Paul’s letter to the Roman church: “For I am convinced that neither death, nor life, nor angels, nor rulers, nor things present, nor things to come, nor powers, nor height, nor depth, nor anything else in all creation, will be able to separate us from the love of God in Christ Jesus our Lord.” (Rom. 8:38-39) As we spend these weeks of Lent in self-examination and introspection, this is well worth remembering. No matter what faults or flaws we may think we find in ourselves, nothing, absolutely nothing can stand in the way of the loving relationship God desires with each of us.

This is one of my favorite bits of theology from St. Paul! This portion of the Letter to the Romans is also in the Epistle Lesson for the Great Vigil of Easter in the Episcopal Church’s lectionary. I love the certitude with which Paul writes: “We will certainly by united with him!” For Paul this is incontrovertible! The Greek word translated “certainly” is alla which has the additional meaning of “nevertheless” or “notwithstanding” – in other words, there is nothing that can stand in the way of our resurrection with Christ. I am reminded of another favorite passage from Paul’s letter to the Roman church: “For I am convinced that neither death, nor life, nor angels, nor rulers, nor things present, nor things to come, nor powers, nor height, nor depth, nor anything else in all creation, will be able to separate us from the love of God in Christ Jesus our Lord.” (Rom. 8:38-39) As we spend these weeks of Lent in self-examination and introspection, this is well worth remembering. No matter what faults or flaws we may think we find in ourselves, nothing, absolutely nothing can stand in the way of the loving relationship God desires with each of us.  St. Paul gave this assurance of God’s commendation to the Corinthians in a discussion which included this reminder, “For all things are yours, whether Paul or Apollos or Cephas or the world or life or death or the present or the future – all belong to you, and you belong to Christ, and Christ belongs to God. Think of us in this way, as servants of Christ and stewards of God’s mysteries.” (1 Cor. 3:21b-4:1) In other words, it’s all about relationship, and how we manage and maintain our relationships will be the basis of God’s judgment. Eugene Peterson in his The Message paraphrases these words, “You are privileged to be in union with Christ, who is in union with God.” It is our relationship, our union with God in Christ that Paul describes as “God’s mysteries.” I recently read another blogger’s suggestion that the way to enhance intimacy in a relationship was to maintain some mystery in it. I believe that blogger is right and that our mysterious relationship with God is the most intimate relationship possible. Lent is a time to explore the mysteries of your relationship with God in Christ, to bring to light things in darkness and to disclose the purposes of both your heart and God’s.

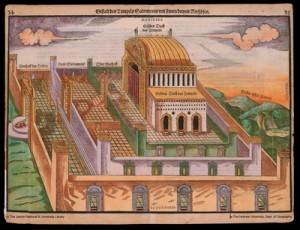

St. Paul gave this assurance of God’s commendation to the Corinthians in a discussion which included this reminder, “For all things are yours, whether Paul or Apollos or Cephas or the world or life or death or the present or the future – all belong to you, and you belong to Christ, and Christ belongs to God. Think of us in this way, as servants of Christ and stewards of God’s mysteries.” (1 Cor. 3:21b-4:1) In other words, it’s all about relationship, and how we manage and maintain our relationships will be the basis of God’s judgment. Eugene Peterson in his The Message paraphrases these words, “You are privileged to be in union with Christ, who is in union with God.” It is our relationship, our union with God in Christ that Paul describes as “God’s mysteries.” I recently read another blogger’s suggestion that the way to enhance intimacy in a relationship was to maintain some mystery in it. I believe that blogger is right and that our mysterious relationship with God is the most intimate relationship possible. Lent is a time to explore the mysteries of your relationship with God in Christ, to bring to light things in darkness and to disclose the purposes of both your heart and God’s. Although I’ve seen this text used (with others) as the foundation for what used to be called “muscular Christianity” (the idea that individual pursuit of physical strength and health are part of the proper Christian life), this text does not state that an individual person is a temple, but rather that a congregation of Christians forms a temple of the Spirit; the pronoun “you” in these verses is in the plural! The first sentence of verse 17 places God’s ultimate condemnation on any individual that damages or destroys a congregation through internal strife or bickering. A congregation of Christians is holy, and its holiness is not to be treated lightly by its members. They should treat one another with respect and dignity, even in the face of disrespect and wrongful treatment. Remember Christ’s admonition to Peter to forgive a brother or sister seventy times seven times. (Matthew 18:22) Paul here shares a metaphor with Peter who wrote to the whole church that all members should, “like living stones, let yourselves be built into a spiritual house.” (1 Peter 2:5) Of course, before stones can be built into a temple, they must be formed and fitted; they must be measured and squared. As living stones, we have the obligation (especially during this season of Lent) to perform this work on ourselves; we are called to do so by responding to God’s grace in Christ Jesus, who is the foundation of our spiritual house, by spiritual growth, faithful living, and testimony to the world. All of that and forgiveness one to another! It is not easy being a living temple! It’s hard work!

Although I’ve seen this text used (with others) as the foundation for what used to be called “muscular Christianity” (the idea that individual pursuit of physical strength and health are part of the proper Christian life), this text does not state that an individual person is a temple, but rather that a congregation of Christians forms a temple of the Spirit; the pronoun “you” in these verses is in the plural! The first sentence of verse 17 places God’s ultimate condemnation on any individual that damages or destroys a congregation through internal strife or bickering. A congregation of Christians is holy, and its holiness is not to be treated lightly by its members. They should treat one another with respect and dignity, even in the face of disrespect and wrongful treatment. Remember Christ’s admonition to Peter to forgive a brother or sister seventy times seven times. (Matthew 18:22) Paul here shares a metaphor with Peter who wrote to the whole church that all members should, “like living stones, let yourselves be built into a spiritual house.” (1 Peter 2:5) Of course, before stones can be built into a temple, they must be formed and fitted; they must be measured and squared. As living stones, we have the obligation (especially during this season of Lent) to perform this work on ourselves; we are called to do so by responding to God’s grace in Christ Jesus, who is the foundation of our spiritual house, by spiritual growth, faithful living, and testimony to the world. All of that and forgiveness one to another! It is not easy being a living temple! It’s hard work! According to the grace of God given to me, like a skilled master builder I laid a foundation, and someone else is building on it. Each builder must choose with care how to build on it. For no one can lay any foundation other than the one that has been laid; that foundation is Jesus Christ. Now if anyone builds on the foundation with gold, silver, precious stones, wood, hay, straw – the work of each builder will become visible, for the Day will disclose it, because it will be revealed with fire, and the fire will test what sort of work each has done.

According to the grace of God given to me, like a skilled master builder I laid a foundation, and someone else is building on it. Each builder must choose with care how to build on it. For no one can lay any foundation other than the one that has been laid; that foundation is Jesus Christ. Now if anyone builds on the foundation with gold, silver, precious stones, wood, hay, straw – the work of each builder will become visible, for the Day will disclose it, because it will be revealed with fire, and the fire will test what sort of work each has done.