====================

This sermon was preached on the Last Sunday after Epiphany, March 2, 2014, at St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Medina, Ohio, where Fr. Funston is rector.

(The lessons for the day were: Exodus 24:12-18; Psalm 2; 2 Peter 1:16-21; and Matthew 17:1-9. These lessons can be read at The Lectionary Page.)

====================

Darmok and Jalad at Tanagra!

Darmok and Jalad at Tanagra!

Darmok and Jalad at Tanagra . . . .

[silence]

Shaka, when the walls fell.

[silence]

Obviously, there is no one here who was a fan of Star Trek: The Next Generation! “Darmok and Jalad at Tanagra” is a line from an episode of that show entitled Darmok in which Picard, the captain of the Enterprise, and the captain of an alien vessel are marooned on a planet called El-Adrel. The alien race are called the Tamarians and their way of communicating is by making metaphorical references to legends, myths, and incidents in their history.

“Darmok and Jalad at Tanagra” is the alien captain’s way of trying to say that he and Picard, the Tamarians and the humans, though strangers can become friends and allies — the reference is to a story in which two strangers become allies against a common enemy. Picard, of course, does not understand and so the Tamarian captain in frustration says, “Shaka, when the walls fell,” a metaphor for failure.

That episode and the Tamarian way of communicating came to mind as I considered the story of the Transfiguration as told by Matthew in today’s Gospel lesson (and referred to in the epistle lesson, as well). The point of the episode is that we all communicate by way of analogy and metaphor; the fictional Tamarians were simply an extreme case. So is religion. All talk of God, all religious language, is metaphorical.

There are anti-religious writers who fail to understand that. I call them “anti-theists” or “evangelical atheists” — they are so sure of the truth of their Godless vision of the universe that they insist on trying to destroy religious faith, to spread the “truth” of their atheism. When they consider the story of the Transfiguration, they insist that it is a made-up story. They point to the fact that the story combines elements of earlier stories of the Hebrew people and say the Gospel writers were simply inventing something.

And, yes, they are right about the earlier stories. In the Book of Daniel, Daniel tells of seeing a vision of heaven in which one he calls “the Ancient One” is clothed in “clothing [which] was white as snow,” (Dan. 7:9) like Matthew (and Mark and Luke) describe Jesus’ clothing on the Holy Mountain. Daniel tells of seeing one “like a son of man” (a title claimed by Jesus, by the way, even in today’s reading) who he describes this way: “His face like lightning, his eyes like flaming torches, his arms and legs like the gleam of burnished bronze.” Matthew doesn’t go into such detail, but he describes Jesus’ face as shining like the sun.

Another earlier story is that of Moses receiving the law from God at Sinai, the story we heard this morning. On that mountain, Moses encountered the Shekinah, the glowing cloud of the Lord’s Presence, not unlike the cloud the Gospel describes on the Mount of the Transfiguration.

What happened on that mountain? I really don’t know. I take the Gospelers’ word for it that something important, something incredible happened. I believe they tried to describe it using stories familiar to their people. Like the fictional Tamarians of Star Trek:TNG, they were reaching back into their history to communicate, by metaphor and analogy, the meaning and importance of a present reality. They were not “making it up,” they were describing it in a way they hoped would make sense. They were trying to communicate that something important happened on that mountain, that in some way Jesus was changed and God spoke to them. I believe that what was of most importance is summarized in three small words: “Listen to him.”

Peter in his second letter — and I know there are scholars who doubt that Peter wrote the second letter attributed to him, but for the moment let’s just go with tradition — Peter in his letter relates his experience on the mountain, and I find it interesting that in doing so, he left out those three words: “[Jesus] received honor and glory from God the Father when that voice was conveyed to him by the Majestic Glory, saying, ‘This is my Son, my Beloved, with whom I am well pleased.’ We ourselves heard this voice come from heaven, while we were with him on the holy mountain.” Peter set a pattern for the church which has continued for nearly 2,000 years. We fail to heed those three small words; we fail to even remember them — and we do not listen to Jesus.

We listen to Paul in his several letters! We listen to John in his three, and to James, and Jude, and Peter. We listen to John of Patmos in the Book of Revelation. We listen to those who came earlier, to Moses, to those who wrote or edited Leviticus and Deuteronomy, to the Prophets, to David in the Psalms. We listen to all of them . . . but we do not listen to Jesus.

All talk of God, all religious language is metaphorical . . . so let me suggest a couple of metaphors that might help us to do so.

I think it was Brian McClaren who said that the way we read the Bible can be likened to an hour glass, which all of the Old Testament being the sand in the top of the glass, and the writings of the New Testament being the sand pouring through the tiny middle, Jesus being that little hole in the center of the glass. We read all that sand in the top as pointing to Jesus, as prophesying Jesus, as explaining why Jesus was going to come. We read all that sand in the bottom of the glass as pointing back to Jesus, as explaining Jesus, as prophesying his return. We read Jesus through the lens of the Old Testament writers or through the lens of the Epistle authors. We listen to what they tell us about Jesus . . . but we do not listen to Jesus.

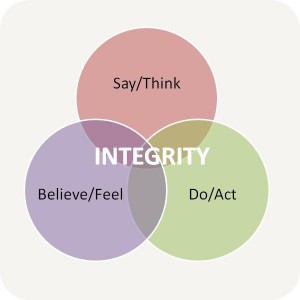

We should stop treating Jesus as the central stem of an hour glass to which all Old Testament sand points forward and to which all New Testament sand points back. We should think of Jesus as the lens of a microscope, or a telescope, or just as a magnifying glass. We should read Paul through the lens of Jesus, not vice versa. We should read Revelation through the lens of Jesus, not vice versa. We should read the prophets, the Psalms, Moses, the whole of the Old Testament through the lens of Jesus. When a biblical writer has something to say about a particular matter, we should hear what that writer has to say, but we should then critically question that writer’s words by asking, “Did Jesus say anything about that?” We should listen to Jesus.

There are many in our society who purport to speak for the church — truth be told, they purport to speak for Jesus — on a variety of topics. For example, we are told that Jesus is opposed to abortion. But when you question that, when you ask for the Biblical basis of their argument, they will cite Genesis: “God created man in his image; in the divine image he created him; male and female he created them” (Gen. 1:27) and then tell you that “when it comes to human dignity, Christ erases distinctions. St. Paul declares, ‘There is neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither slave or free person, there is not male and female; for you are all one in Christ Jesus’ (Galatians 3:28). We can likewise say, ‘There is neither born nor unborn.'” This is an actual quotation from an antiabortion website. Notice what was done: Christ, we are told, erases distinctions, but it is Paul who is cited. This is reading Jesus through the lens of Paul; this is listening to Paul, not Jesus.

Did Jesus ever say anything about abortion? No. Never. What did Jesus say? “Love God; love your neighbor as yourself.” Sometimes our neighbor must make very hard, very painful decisions, but never did Jesus suggest we are to make her decisions for her, or to prevent her from making her own decisions, or to question the decision she may make. Quite to the contrary, he said, “Do not judge, and you will not be judged; do not condemn, and you will not be condemned.” (Luke 6:37) Listen to him.

We are told that Jesus condemns those who engaged in sexual immorality, but did Jesus do so? On one occasion, he encountered a crowd which was intent on executing (as the law demanded) a woman who had been exposed as an adulterer. What did he do and say? He convinced the crowd to abandon their plans. When the crowd left while he was looking away, Jesus said to the woman, “Woman, where are they? Has no one condemned you?” She said, “No one, sir.” And Jesus said, “Neither do I condemn you. Go your way, and from now on do not sin again.” (John 8:10-11) Jesus had a lot to say about sexual immorality, but when dealing with some accused of it, he followed his own rule: Love your neighbor, and do not judge. Listen to him.

We are told that Jesus condemns homosexuality, that gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgendered persons should be excluded from ministry, that they should be forbidden to marry the person they love. Did Jesus ever say anything about same-sex relationships? No, never. Leviticus has something to say about, though scholars are in conflict about whether that has any application to committed, loving adult relationships. St. Paul had something to say about, maybe. There is the same doubt about the application of his words to committed, loving adult relationships. There is even some doubt about whether Paul’s words are anything more than a cut-and-paste use of a Greek rhetorical form. But Jesus? Jesus never even said anything about which there could be doubt; about homosexual relationships, Jesus said nothing . . . nothing other than “Love your neighbor, and do not judge.” Listen to him.

We do this over and over again throughout history, whatever the issue of the day may be. Go back about a hundred years; go back to the temperance movement of the early 20th Century. Members of the Church campaigned against “demon rum” on the grounds that Jesus was against drinking. Did Jesus ever say anything about alcoholic beverages? Yes! He said to drink them! And, especially, he said to do so in his memory. Listen to him!

My systematic theology professor, Jim Griffis, was very good at dealing with students who wanted to read Jesus through the lens of other Scripture. He would listen to them cite the Old Testament or Paul or Revelation, and then ask, “What does Jesus say?” “The Gospel,” he would say, “trumps the Bible.” The Gospel of love: Love God; love your neighbor; do not judge. Understand everything else through that critical filter.

Something happened on the mount of the Transfiguration, something so important that those who later wrote about it and preserved it, analogized it to the important stories of their past. Like the Tamarian captain looking back to Darmok and Jalad at Tanagra, they looked back to Moses receiving the law at Sinai, to Daniel seeing a vision of heaven.

There is one more similarity between those earlier bible stories and the tale of the Transfiguration. In Daniel’s vision, the one “like a son of man” says to Daniel, “Pay attention to the words that I am going to speak to you.” (Dan. 10:11) The three most important words spoken on the Holy Mountain are “Listen to him!” — Listen to Paul, listen to Moses, listen to John of Patmos, listen to the prophets, listen to David . . . but, most importantly, listen to Jesus and understand all the rest through that lens: “Love God. Love your neighbor as yourself. Do not judge.”

“This is my son, the beloved; in him I am well pleased. Listen to him.”

Amen.

====================

A request to my readers: I’m trying to build the readership of this blog and I’d very much appreciate your help in doing so. If you find something here that is of value, please share it with others. If you are on Facebook, “like” the posts on your page so others can see them. If you are following me on Twitter, please “retweet” the notices of these meditations. If you have a blog of your own, please include mine in your links (a favor I will gladly reciprocate). Many thanks!

====================

Father Funston is the rector of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Medina, Ohio.

This is such a great set up! Here are these Greeks (whether gentiles or Greek-speaking Jews of the Diaspora is unclear) who want to meet Jesus. They come to Philip who apparently speaks Greek and make their request. He goes to Andrew (another unclear thing: does he take the Greeks with him?) The two of them go see Jesus (with the Greeks?)

This is such a great set up! Here are these Greeks (whether gentiles or Greek-speaking Jews of the Diaspora is unclear) who want to meet Jesus. They come to Philip who apparently speaks Greek and make their request. He goes to Andrew (another unclear thing: does he take the Greeks with him?) The two of them go see Jesus (with the Greeks?)  There’s really very little in the Bible that makes me angry. I find a good deal to object to, to be annoyed by, and to wish wasn’t there, but very little that riles me. Paul’s letter to his friend Philemon, however, just plain pisses me off.

There’s really very little in the Bible that makes me angry. I find a good deal to object to, to be annoyed by, and to wish wasn’t there, but very little that riles me. Paul’s letter to his friend Philemon, however, just plain pisses me off. Last evening while driving home from the midweek Eucharist, I listened to a program on the local NPR station in which the host and a guest were discussing the internet coverage of news. One of the things mentioned was that the analytics on a British tabloid’s website had demonstrated that a story about Taylor Swift’s legs had garnered more “clicks” and more viewing time than a simultaneously run story about the world-wide affects of global climate change – something on the order of 400% more! The discussion continued with similar examples of stories about Kim Kardashian and her “rear end,” Justin Bieber’s legal problems, and more.

Last evening while driving home from the midweek Eucharist, I listened to a program on the local NPR station in which the host and a guest were discussing the internet coverage of news. One of the things mentioned was that the analytics on a British tabloid’s website had demonstrated that a story about Taylor Swift’s legs had garnered more “clicks” and more viewing time than a simultaneously run story about the world-wide affects of global climate change – something on the order of 400% more! The discussion continued with similar examples of stories about Kim Kardashian and her “rear end,” Justin Bieber’s legal problems, and more. The words of Caiaphas the high priest are reported by John as a prophecy that Jesus’ death would be an atoning sacrifice, that he would “die for the nation, and not for the nation only, but to gather into one the dispersed children of God.” (vv. 51-52) But I read them this morning as nothing more than political calculation.

The words of Caiaphas the high priest are reported by John as a prophecy that Jesus’ death would be an atoning sacrifice, that he would “die for the nation, and not for the nation only, but to gather into one the dispersed children of God.” (vv. 51-52) But I read them this morning as nothing more than political calculation.  My favorite thing in the Book of Proverbs is the personification of Lady Wisdom. Perhaps because of the further development of her portrait in Chapter 8, where she is said to have been with God in the moments of creation, “daily his delight, rejoicing before him always, rejoicing in his inhabited world and delighting in the human race” (vv. 30-31), I see her as young, slender, and athletic, her rejoicing being manifest as dance.

My favorite thing in the Book of Proverbs is the personification of Lady Wisdom. Perhaps because of the further development of her portrait in Chapter 8, where she is said to have been with God in the moments of creation, “daily his delight, rejoicing before him always, rejoicing in his inhabited world and delighting in the human race” (vv. 30-31), I see her as young, slender, and athletic, her rejoicing being manifest as dance. How does one “test the spirits”? How does one divine the promptings of the spirit or determine the will of God? That’s always the question we must face. In the ancient tabernacle, the high priest’s vestments included a breastplate in which he kept a couple of stones called the urim and the thummim (Exodus 28:30). What those were is a subject of much speculation, but one theory is that they were sort of like dice. The belief is that the high priest cast these dice to determine God’s guidance, to “test the spirit” when faced with a difficult decision.

How does one “test the spirits”? How does one divine the promptings of the spirit or determine the will of God? That’s always the question we must face. In the ancient tabernacle, the high priest’s vestments included a breastplate in which he kept a couple of stones called the urim and the thummim (Exodus 28:30). What those were is a subject of much speculation, but one theory is that they were sort of like dice. The belief is that the high priest cast these dice to determine God’s guidance, to “test the spirit” when faced with a difficult decision. Jesus doesn’t ask much, does he? Only perfection! “Be perfect,” he tells us, “as your heavenly Father is perfect.” Of course, Jesus is simply echoing the words Moses spoke on God’s behalf delivering the Law to the Hebrews: “You shall be holy, for I the Lord your God am holy.” What can this mean? How can we be expected to be perfect and holy like God? How can we do that, especially when both Moses and Jesus insist that that means, among other things, loving our enemies, not seeking redress, not holding a grudge, and not getting that to which we are sure we are entitled?

Jesus doesn’t ask much, does he? Only perfection! “Be perfect,” he tells us, “as your heavenly Father is perfect.” Of course, Jesus is simply echoing the words Moses spoke on God’s behalf delivering the Law to the Hebrews: “You shall be holy, for I the Lord your God am holy.” What can this mean? How can we be expected to be perfect and holy like God? How can we do that, especially when both Moses and Jesus insist that that means, among other things, loving our enemies, not seeking redress, not holding a grudge, and not getting that to which we are sure we are entitled? This, for me, is the issue of our day. It is the religious issue. It is the economic issue. It is the political issue. It is the moral issue. I think the answer to John’s question is, “It doesn’t.”

This, for me, is the issue of our day. It is the religious issue. It is the economic issue. It is the political issue. It is the moral issue. I think the answer to John’s question is, “It doesn’t.”