Revised Common Lectionary for Maundy Thursday, Year B: Exodus 12:1-14; Psalm 116:1,10-17; 1 Corinthians 11:23-26; John 13:1-17, 31b-35

Redemption is a drama in three acts – three acts and a brief intermission – tonight we take part in Act One.

Act One, Scene One: The curtain rises. We see a group of people gathered in an upper room somewhere in Jerusalem.

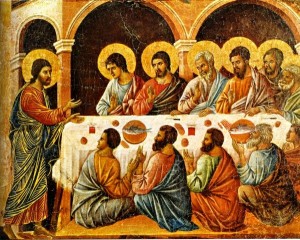

A meal is in progress… Is it a seder, the ritual meal of remembrance of the Passover? We don’t really know; the playwrights have not made this clear; the theater critics, the scholars debate this issue. Three of the story-tellers suggest that it is but the fourth, John, tells the tale very differently. (The synoptic gospels tell the story in a similar way and, if truth be told, in the same way – Luke and Matthew based their stories on Mark’s, so to be honest there aren’t three stories, there’s only one that would make us think that this supper is a seder, but John doesn’t. In fact, John doesn’t even care about that – he spends no time at all describing the meal, for him the important thing is what happened afterward, and that comes in a later scene. So as we begin this three-day, three-act drama of redemption, since we have heard Luke’s voice narrating the story, let’s just assume that what we see in this first scene of the first act is, indeed, a seder.)

A meal is in progress… Is it a seder, the ritual meal of remembrance of the Passover? We don’t really know; the playwrights have not made this clear; the theater critics, the scholars debate this issue. Three of the story-tellers suggest that it is but the fourth, John, tells the tale very differently. (The synoptic gospels tell the story in a similar way and, if truth be told, in the same way – Luke and Matthew based their stories on Mark’s, so to be honest there aren’t three stories, there’s only one that would make us think that this supper is a seder, but John doesn’t. In fact, John doesn’t even care about that – he spends no time at all describing the meal, for him the important thing is what happened afterward, and that comes in a later scene. So as we begin this three-day, three-act drama of redemption, since we have heard Luke’s voice narrating the story, let’s just assume that what we see in this first scene of the first act is, indeed, a seder.)

Those present are prepared to do all that is laid out in the instructions in the book of Exodus; they have worn their sandals; they carry their staffs; they expect to eat of roasted lamb and unleavened bread and bitter herbs. They anticipate spending the night in remembrance of that which happened generations before in Egypt. If we can imagine that they celebrate as modern Jews celebrate, they expect the youngest among them to ask the questions, beginning with “Why is this night different from all other nights?” They know that the head of the household, their rabbi Jesus, will answer those questions in the prescribed way and tell the story of the Passover.

And when the youngest asks “Why do we eat the broken matzah?” they expect Jesus to answer “This is the bread of our affliction; the unleavened bread of poverty, baked and eaten in haste,” but instead he takes the bread, brakes it and says, “This bread is my body, given for you.”

Can’t you just see them in this scene, reclining in that upper room, those serving the meal coming and going, a breeze blowing through the open windows, following along in their prayer books, the Haggadah … They look up startled, glancing at one another, murmuring to each other, “What is he talking about? That’s not here! That’s not the right answer. Where is he? What page is he on?” But the moment passes, the meal moves on, until at the end he takes up the fourth and final cup of wine, the kiddush cup, which recalls God’s promise, “I will acquire you as a nation; you will be my people and I will be your God.” They expect Jesus to say, “Blessed are you, O Lord our God, sovereign of the universe, creator of the fruit of the vine,” but instead they hear, “This cup is my blood!” “What?! What is he saying???”

It is for Jesus and his disciples one of those fleeting opportunities when, because of the pupils’ confusion or frustration or grasping for understanding, the teacher can pass on to the students new information, new values, new moral understanding, a new behavior, a new skill, a new way of seeing and coping with reality; it is what we have come to call “the teachable moment” and so he teaches, yet again, “Remember! Remember,” he says, “Love one another as I have loved you.”

The curtain falls as Jesus continues to teach; the disciples look mystified.

Act One, Scene Two: The curtain rises again. We see the same group of people gathered in the same upper room somewhere in Jerusalem.

The meal is over, the dishes have been cleared. The disciples are arguing among themselves about who is the greater among them. Jesus looks frustrated and troubled; the teachable moment has passed and they clearly have not understood! They just haven’t gotten it.

The meal is over, the dishes have been cleared. The disciples are arguing among themselves about who is the greater among them. Jesus looks frustrated and troubled; the teachable moment has passed and they clearly have not understood! They just haven’t gotten it.

“Look,” he says, “the greatest among you must become like the youngest, and the leader like one who serves. For who is greater, the one who is at the table or the one who serves? Is it not the one at the table? But I am among you as one who serves. Here, let me show you what I mean.” Getting up from the table, he takes off his robe, ties a towel around himself, pours water into a basin, and begins to wash and dry the others’ feet. Peter protests, “You will never wash my feet.” Jesus answers, “Peter, if I don’t wash you, you can’t be part of what I’m doing.” So Peter relents, “Well then, not only my feet! Wash my hands and my head, too!”

Peter speaks for us. We don’t get this foot-washing thing, do we? Washing our hands makes more sense to us, as it does to Anglican nun and poet Lucy Nanson who wrote:

Wash my hands on Maundy Thursday

not my feet

My hands peel potatoes, wipe messes from the floor

change dirty nappies, clean the grease from pots and pans

have pointed in anger and pushed away in tears

in years past they’ve smacked a child and raised a fist

fumbled with nervousness, shaken with fear

I’ve wrung them when waiting for news to come

crushed a letter I’d rather forget

covered my mouth when I’ve been caught out

touched forbidden things, childhood memories do not grow dim

These hands have dug gardens, planted seeds

picked fruit and berries, weeded out and pruned trees

found bleeding from the rose’s thorns

dirt and blood mix together

when washed before a cup of tea

Love expressed by them

asks for your respect

in the hand-shake of warm greeting,

the gentle rubbing of a child’s bump

the caressing of a lover, the softness of a baby’s cheek

sounds of music played by them in tunes upon a flute

they’ve held a frightened teenager,

touched a father in his death

where cold skin tells the end of life has come

but not the end of love,

comforted a mother losing agility and health.

With my hands outstretched before you

I stand humbled and in awe

your gentle washing in water, the softness of the towel

symbolizing a cleansing

the servant-hood of Christ.

Wash my hands on Maundy Thursday

and not my feet.

Yes, Peter speaks for us; we would rather our hands be washed. But Jesus insists, he must wash his disciples feet for only in this way does one truly honor and serve another in love, only in this way does one recall whose servant one is. He says to them, “If I, your master and teacher, have washed your feet, you must now wash each other’s feet.” Only in this way can his disciples remember his teaching that what is done for us is also to be done for others.

They don’t get the opportunity, however, for the second scene ends as Jesus becomes visibly agitated and declares, “One of you is going to betray me.”

As the curtain goes down, the disciples are looking puzzled and Judas Iscariot is leaving.

Act One, Scene Three: The curtain rises again. We see a garden and an olive grove just outside of Jerusalem. Jesus is there, accompanied by Peter, James, and John.

“Stay here,” he tells them, “Stay awake while I go over there to pray.” As they settle themselves, he moves away from them, and collapses in a heap, sobbing: “O God … Father, let this pass!”

“Stay here,” he tells them, “Stay awake while I go over there to pray.” As they settle themselves, he moves away from them, and collapses in a heap, sobbing: “O God … Father, let this pass!”

Three times he returns to find them asleep; three times they rise looking sheepish and embarrassed; twice he tells them again to try to stay awake as he goes away still pleading with God for a way out. “Enough,” he says the third time, “Enough! We’re leaving.”

When they look back on that night, how must they feel? When we look back, how should we feel?

Poet Mary Oliver offers a glimpse in her poem Gethsemane:

The grass never sleeps.

Or the roses.

Nor does the lily have a secret eye that shuts until morning.

Jesus said, wait with me. But the disciples slept.

The cricket has such splendid fringe on its feet,

and it sings, have you noticed, with its whole body,

and heaven knows if it ever sleeps.

Jesus said, wait with me. And maybe the stars did,

maybe the wind wound itself into a silver tree,

and didn’t move, maybe the lake far away,

where once he walked as on a blue pavement,

lay still and waited, wild awake.

Oh the dear bodies, slumped and eye-shut, that could not

keep that vigil, how they must have wept,

so utterly human, knowing this too

must be part of the story.

Yes, this too, our utterly human inability to fully keep company with our Lord, this too must be part of the story when it is told, as we see it unfold in the church’s memory tonight, but for now the stage fills, the garden becomes crowded … Judas returns accompanied by temple guards, and Roman soldiers, and servants of the priests … and are those some of the disciples showing up? The orchard of olives suddenly is filled with angry activity, with scuffling, with fighting, with confusion. Peter calls out, “Lord, should we fight back?” and, without waiting for an answer, draws his sword and cuts off a servant’s ear.

“Stop!” cries Jesus. He reaches out and tenderly touches the servant’s head, healing his wound. He seems sadly confused, “Why have you come to arrest me with swords drawn?” he asks, “I’ve been teaching in the temple all week! You could have taken me any time.” It all seems too much for him. Certainly, it’s too much for us! Again, a poet, Ted Loder, speaks for us:

Sometimes, Lord,

it just seems to be too much:

too much violence, too much fear;

too much of demands and problems;

too much of broken dreams and broken lives;

too much of wars and slums and dying:

too much of greed and squishy fatness

and the sounds of people

devouring each other

and the earth;

too much of stale routines and quarrels,

unpaid bills and dead ends;

too much of words lobbed in to explode

leaving shredded hearts and lacerated souls;

too much of turned-away backs and yellow silence,

red rage and the bitter taste of ashes in my mouth.

Sometimes the very air seems scorched

by threats and rejection and decay

until there is nothing

but to inhale pain

and exhale confusion.

Too much of darkness, Lord,

too much of cruelty

and selfishness

and indifference.

Too much, Lord

too much,

too bloody,

bruising,

brain-washing much.

Or is it too little,

too little of compassion,

too little of courage,

of daring,

of persistence,

[too little] of sacrifice?

Jesus and his captors exit; the disciples, confused and frightened, sneak out behind them. The curtain falls. We are left in darkness….

Let us pray:

Heavenly Father, as we enter again into the mystery of these three most holy days, as we participate once again in this three-act drama of redemption, we ask you to illumine our minds and hearts with the hope and promise of Christ’s passion, death, and resurrection; satisfy our hunger and thirst not for bread and drink alone, but for love, and truth, and justice, and peace; as we share your Son’s Body and Blood, renew us and energize us to be a true community of light amid the darkness of sin and injustice in our world; as Jesus invites us to share at his Table, let us in turn invite our brothers and sisters to the table where all can share the resources of your abundance, where justice and peace reign, and where love transforms souls and societies; as the drama of redemption continues, may life conquer death, may light shine in the darkness, and may courage and compassion grow from sacrifice; in Christ’s holy Name we pray. Amen.

Jethro, Moses’ father-in-law, has to have been one of the wisest men in all of Holy Scripture! What he advises Moses to do is nothing less that to delegate authority and responsibility. Delegation is one of the most important management skills. Good delegation saves time, develops people, grooms successors, and motivates subordinates. Poor delegation will causes frustration,confuses subordinates, discourages others, and leads to failure of purpose. Delegation is vital for effective leadership. Jethro seems to have known this and recommended it to Moses: “Look for able men among all the people, men who fear God, are trustworthy, and hate dishonest gain; set such men over them as officers over thousands, hundreds, fifties and tens.” (Exod. 18:21) ~ Here’s the thing, though, delegation means letting go! Once you have handed over authority, you cannot dictate what is delegated nor how that delegation is to be managed. Delegation means letting go and letting go is hard. Human beings, especially talented and successful ones, are reluctant to let go of the things we do well. It’s simply human nature. But refusal to hand-over jobs to subordinates minimizes our productivity and effectiveness. We need to learn to let go. That, by the way, is the message of Christ. Jethro anticipated Jesus: “Do not worry about tomorrow, for tomorrow will bring worries of its own. Today’s trouble is enough for today.” (Matt. 6:34) In other words, let go! ~ When I was in college there was a bumper sticker popular among church-going Christians of a particular sort. It read, “Let go and let God”. And I know it’s also a catch-phrase for twelve-steppers and apparently it works for them…. but I hated it then and I don’t like it any better now! I think it misinterprets and trivializes the Christian message, what it means to be an active and responsible Christian. Jesus, in fact, never tells us to “let go and let God”. “Letting go” in this catch-phrase seems to imply that one do nothing, say nothing, feel nothing, and accept responsibility for nothing. That is neither what Jesus said, nor what Jethro advised Moses! Jethro told Moses to continue to be involved: “Let them sit as judges for the people at all times; let them bring every important case to you, but decide every minor case themselves.” (Exod. 18:22) Every good manager knows that delegation doesn’t mean complete relinquishment of responsibility, and every good Christian ought to know that “letting go” doesn’t mean just shrugging everything off onto God’s plate! Yes, we need to learn to let go, but letting go means letting go of tension, anxiety, worry . . . not of all responsibility. God has high expectations of us! That bumper sticker catch phrase fails to acknowledge that. ~ The fellow who said “Do not worry about tomorrow . . .” is also the man who said “Beware, keep alert . . .”, the man who said “[When] you did it to one of the least of these who are members of my family, you did it to me.” (Mark 13:33; Matt. 2:40) We are not to abandon our responsibilities; we are to meet them in a non-anxious way in community working with others. That is what “letting go” means. That is what God expects of us; that is what Jethro advised Moses.

Jethro, Moses’ father-in-law, has to have been one of the wisest men in all of Holy Scripture! What he advises Moses to do is nothing less that to delegate authority and responsibility. Delegation is one of the most important management skills. Good delegation saves time, develops people, grooms successors, and motivates subordinates. Poor delegation will causes frustration,confuses subordinates, discourages others, and leads to failure of purpose. Delegation is vital for effective leadership. Jethro seems to have known this and recommended it to Moses: “Look for able men among all the people, men who fear God, are trustworthy, and hate dishonest gain; set such men over them as officers over thousands, hundreds, fifties and tens.” (Exod. 18:21) ~ Here’s the thing, though, delegation means letting go! Once you have handed over authority, you cannot dictate what is delegated nor how that delegation is to be managed. Delegation means letting go and letting go is hard. Human beings, especially talented and successful ones, are reluctant to let go of the things we do well. It’s simply human nature. But refusal to hand-over jobs to subordinates minimizes our productivity and effectiveness. We need to learn to let go. That, by the way, is the message of Christ. Jethro anticipated Jesus: “Do not worry about tomorrow, for tomorrow will bring worries of its own. Today’s trouble is enough for today.” (Matt. 6:34) In other words, let go! ~ When I was in college there was a bumper sticker popular among church-going Christians of a particular sort. It read, “Let go and let God”. And I know it’s also a catch-phrase for twelve-steppers and apparently it works for them…. but I hated it then and I don’t like it any better now! I think it misinterprets and trivializes the Christian message, what it means to be an active and responsible Christian. Jesus, in fact, never tells us to “let go and let God”. “Letting go” in this catch-phrase seems to imply that one do nothing, say nothing, feel nothing, and accept responsibility for nothing. That is neither what Jesus said, nor what Jethro advised Moses! Jethro told Moses to continue to be involved: “Let them sit as judges for the people at all times; let them bring every important case to you, but decide every minor case themselves.” (Exod. 18:22) Every good manager knows that delegation doesn’t mean complete relinquishment of responsibility, and every good Christian ought to know that “letting go” doesn’t mean just shrugging everything off onto God’s plate! Yes, we need to learn to let go, but letting go means letting go of tension, anxiety, worry . . . not of all responsibility. God has high expectations of us! That bumper sticker catch phrase fails to acknowledge that. ~ The fellow who said “Do not worry about tomorrow . . .” is also the man who said “Beware, keep alert . . .”, the man who said “[When] you did it to one of the least of these who are members of my family, you did it to me.” (Mark 13:33; Matt. 2:40) We are not to abandon our responsibilities; we are to meet them in a non-anxious way in community working with others. That is what “letting go” means. That is what God expects of us; that is what Jethro advised Moses. I have to admit that I would be hard-pressed to choose one of the many post-resurrection appearances of Christ as my favorite. Each one recorded in Scripture is so full of vivid imagery and meaning that it would be nearly impossible to put one above another … having said that, however, I also have to admit an especial fondness for the one described here by Luke.

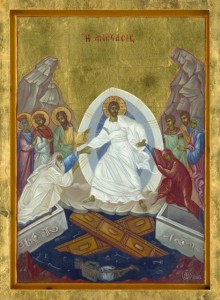

I have to admit that I would be hard-pressed to choose one of the many post-resurrection appearances of Christ as my favorite. Each one recorded in Scripture is so full of vivid imagery and meaning that it would be nearly impossible to put one above another … having said that, however, I also have to admit an especial fondness for the one described here by Luke.  In some ancient manuscripts of this “longer ending” of Mark’s Gospel the text above continues with the following response by the apostles: “And they excused themselves, saying, ‘This age of lawlessness and unbelief is under Satan, who does not allow the truth and power of God to prevail over the unclean things of the spirits. Therefore reveal your righteousness now’ – thus they spoke to Christ.” Jesus says a few nearly incomprehensible words about Satan’s power ending in this age and so forth, and then the text picks up with the received version’s comments about snake-handling and poison-drinking. ~ I absolutely love this first part of that addition: the fact that “they excused themselves” and that they demanded of Jesus “reveal your righteousness now”. I love it! It’s so darned modern . . . or maybe even post-modern. I can almost hear them saying something like, “Well, Jesus, that resurrection stuff may be true for you, but it’s not true for us!” Making excuses, making demands, relativizing the situation . . . these men aren’t just First Century Palestinian Jews; they are 21st Century Americans; they are US! ~ Well, actually, they aren’t. Where they differ is that after this confrontation with the Risen Christ, they got up off their duffs and went to work. “They went out and proclaimed the good news everywhere, while the Lord worked with them and confirmed the message by the signs that accompanied it.” (Mark 16:20) Very few excuse-making, demanding, relativizing, modern American church members do anything like that! ~ For nearly forty years, since Authorized Services, 1973 (a precursor to the current American Book of Common Prayer), at every baptism, the Episcopal Church has been asking its members if they will “proclaim by word and example the Good News of God in Christ” and those members have answered affirmatively, “I will, with God’s help.” However, when we discuss evangelism, inviting people to church, talking with others about one’s faith, and similar topics, it becomes painfully clear that very few of those Episcopalians are actually doing so. And it does no good to confront them with that failure; they excuse themselves, just like the apostles! And just like the apostles, many of them make note of the fact that they don’t see much response when they try, that God doesn’t seem to be helping much. ~ Maybe we need to confront God, just like the apostles . . . maybe we need to say to God, as the apostles said to their risen Lord, “Reveal your righteousness now.” After all, when they went out and spread the gospel “the Lord worked with them and confirmed the message” with “signs” . . . we could use a few signs right now. ~ Yesterday, I made mention here of those times when it’s hard to see Jesus, when we fail to recognize him. I think we must all admit that there are times like that, when we do not see God, when we cannot feel God’s presence, when God seems to be silent. One of the most important books I read while in theological study was Hope in Time of Abandonment (Seabury 1973) by the French Protestant philosopher Jacques Ellul. In it Ellul wrote, “Hope comes alive only in the dreary silence of God, in our loneliness before a closed heaven, in our abandonment . . . Hope is a protest before this God, who is leaving us without miracles and without conversions, that he is not keeping his Word.” Hope, said Ellul, is humanity’s answer to God’s silence and it is through prayer that we demand the fulfillment of God’s promise. ~ If God is not living up to God’s promise to support the work of Jesus’ present-day apostles with confirming signs, then perhaps we Episcopalians who excuse ourselves from fulfilling our promise in the baptismal covenant are not to be faulted. Perhaps, like those first apostles we should be demanding of God in Christ, “Reveal your righteousness now!” ~ On the other hand, if God is living up to God’s promises and we just aren’t seeing that . . . .

In some ancient manuscripts of this “longer ending” of Mark’s Gospel the text above continues with the following response by the apostles: “And they excused themselves, saying, ‘This age of lawlessness and unbelief is under Satan, who does not allow the truth and power of God to prevail over the unclean things of the spirits. Therefore reveal your righteousness now’ – thus they spoke to Christ.” Jesus says a few nearly incomprehensible words about Satan’s power ending in this age and so forth, and then the text picks up with the received version’s comments about snake-handling and poison-drinking. ~ I absolutely love this first part of that addition: the fact that “they excused themselves” and that they demanded of Jesus “reveal your righteousness now”. I love it! It’s so darned modern . . . or maybe even post-modern. I can almost hear them saying something like, “Well, Jesus, that resurrection stuff may be true for you, but it’s not true for us!” Making excuses, making demands, relativizing the situation . . . these men aren’t just First Century Palestinian Jews; they are 21st Century Americans; they are US! ~ Well, actually, they aren’t. Where they differ is that after this confrontation with the Risen Christ, they got up off their duffs and went to work. “They went out and proclaimed the good news everywhere, while the Lord worked with them and confirmed the message by the signs that accompanied it.” (Mark 16:20) Very few excuse-making, demanding, relativizing, modern American church members do anything like that! ~ For nearly forty years, since Authorized Services, 1973 (a precursor to the current American Book of Common Prayer), at every baptism, the Episcopal Church has been asking its members if they will “proclaim by word and example the Good News of God in Christ” and those members have answered affirmatively, “I will, with God’s help.” However, when we discuss evangelism, inviting people to church, talking with others about one’s faith, and similar topics, it becomes painfully clear that very few of those Episcopalians are actually doing so. And it does no good to confront them with that failure; they excuse themselves, just like the apostles! And just like the apostles, many of them make note of the fact that they don’t see much response when they try, that God doesn’t seem to be helping much. ~ Maybe we need to confront God, just like the apostles . . . maybe we need to say to God, as the apostles said to their risen Lord, “Reveal your righteousness now.” After all, when they went out and spread the gospel “the Lord worked with them and confirmed the message” with “signs” . . . we could use a few signs right now. ~ Yesterday, I made mention here of those times when it’s hard to see Jesus, when we fail to recognize him. I think we must all admit that there are times like that, when we do not see God, when we cannot feel God’s presence, when God seems to be silent. One of the most important books I read while in theological study was Hope in Time of Abandonment (Seabury 1973) by the French Protestant philosopher Jacques Ellul. In it Ellul wrote, “Hope comes alive only in the dreary silence of God, in our loneliness before a closed heaven, in our abandonment . . . Hope is a protest before this God, who is leaving us without miracles and without conversions, that he is not keeping his Word.” Hope, said Ellul, is humanity’s answer to God’s silence and it is through prayer that we demand the fulfillment of God’s promise. ~ If God is not living up to God’s promise to support the work of Jesus’ present-day apostles with confirming signs, then perhaps we Episcopalians who excuse ourselves from fulfilling our promise in the baptismal covenant are not to be faulted. Perhaps, like those first apostles we should be demanding of God in Christ, “Reveal your righteousness now!” ~ On the other hand, if God is living up to God’s promises and we just aren’t seeing that . . . . “A little while, and you will no longer see me, and again a little while, and you will see me.” Say, what? I have to admit that I have the same reaction to what Jesus says here that the disciples seem to have – a sort of scratching of the head and wondering, “What the heck does that mean?” ~ On the other hand, when I read that statement what immediately comes to mind is that traveling carnival arcade game “Whack-a-Mole” – the one where the rodent pops up unexpectedly from holes and you’re supposed to hit it with a mallet! Undoubtedly, someone will tell me that I’m being blasphemous or sacrilegious or something, but the image that comes to my mind is that game with Jesus popping up out of the holes – “Now you see me. Now you don’t. A little while . . . you’ll see me again. Try to get me!” ~ And truly, that is the way Jesus sometimes “pops up” in my life. I see Jesus in the hungry who come to my church’s food pantry on Saturday mornings and in the volunteers who serve them, but then sometimes on Sunday I wonder where he is: “He was here yesterday. Why isn’t he here now?” Or sometimes, I do see him on Sunday morning in the wonder and glory of worship and in the fellowship among parishioners during coffee hour, but then on Monday I see folks I know driving less-than-courteously in what my daughter calls “gas guzzling SUVs” (confession: I drive one, too) and I wonder: “Where’s Jesus?” He pops up, I see him, he disappears, I don’t see him, a little while . . . there he is again. Like that darned rodent popping up in the game! ~ I know full and well that this is not what Jesus was talking about to the disciples. I know he’s talking about his crucifixion and his resurrection and his ascension; I know that . . . but I still see that “Whack-a-Mole” game in my mind’s eye! That’s one of the beauties of Scripture, that we can find applications of the text in situations that may not be exactly what the original story was about, but that are nonetheless related and valid. Jesus may have been talking about his immediate return in the resurrection, but he also returns in his community through the ages. The original disciples didn’t see him and then they did; church members today are still seeing him in many places and contexts. Sometimes we don’t, but then in a little while, we do. ~ I’m terrible at “Whack-a-Mole”, by the way. I have lousy reaction times with such things, always have – it’s why I was terrible at sports like baseball or tennis in elementary, junior high, and high schools. But I was good at shooting guns. I went to a military high school where we were required to pass Army ROTC firearms tests. I qualified as either a “marksman” or an “expert” with every weapon on which we trained. I was also pretty good at archery. Did you know that the New Testament word for “sin” comes from the sport of archery? It’s hamartia, which means “missing the mark”. Aristotle (384-322 BC) borrowed the term and used it in his Poetics to describe the “fatal flaw” in the hero of a dramatic tragedy; the writers of the New Testament then used it to mean “sin”. ~ So, sometimes I don’t see Jesus when I ought to. It’s not that Jesus isn’t there; it’s just that I don’t see him or if I do, like not reacting to the mole fast enough, I don’t recognize him. Like playing “Whack-a-Mole” and failing to hit the rodent, my reaction timing is just not right and I “miss the mark”. I sin by failing to “whack” when Jesus pops up! Therein lies the spiritual discipline to which this text calls me – to look, to recognize, to hone my reaction time, to respond quickly and affirmatively, and (if you’ll pardon some really blatant sacrilege) to Whack-a-Jesus!

“A little while, and you will no longer see me, and again a little while, and you will see me.” Say, what? I have to admit that I have the same reaction to what Jesus says here that the disciples seem to have – a sort of scratching of the head and wondering, “What the heck does that mean?” ~ On the other hand, when I read that statement what immediately comes to mind is that traveling carnival arcade game “Whack-a-Mole” – the one where the rodent pops up unexpectedly from holes and you’re supposed to hit it with a mallet! Undoubtedly, someone will tell me that I’m being blasphemous or sacrilegious or something, but the image that comes to my mind is that game with Jesus popping up out of the holes – “Now you see me. Now you don’t. A little while . . . you’ll see me again. Try to get me!” ~ And truly, that is the way Jesus sometimes “pops up” in my life. I see Jesus in the hungry who come to my church’s food pantry on Saturday mornings and in the volunteers who serve them, but then sometimes on Sunday I wonder where he is: “He was here yesterday. Why isn’t he here now?” Or sometimes, I do see him on Sunday morning in the wonder and glory of worship and in the fellowship among parishioners during coffee hour, but then on Monday I see folks I know driving less-than-courteously in what my daughter calls “gas guzzling SUVs” (confession: I drive one, too) and I wonder: “Where’s Jesus?” He pops up, I see him, he disappears, I don’t see him, a little while . . . there he is again. Like that darned rodent popping up in the game! ~ I know full and well that this is not what Jesus was talking about to the disciples. I know he’s talking about his crucifixion and his resurrection and his ascension; I know that . . . but I still see that “Whack-a-Mole” game in my mind’s eye! That’s one of the beauties of Scripture, that we can find applications of the text in situations that may not be exactly what the original story was about, but that are nonetheless related and valid. Jesus may have been talking about his immediate return in the resurrection, but he also returns in his community through the ages. The original disciples didn’t see him and then they did; church members today are still seeing him in many places and contexts. Sometimes we don’t, but then in a little while, we do. ~ I’m terrible at “Whack-a-Mole”, by the way. I have lousy reaction times with such things, always have – it’s why I was terrible at sports like baseball or tennis in elementary, junior high, and high schools. But I was good at shooting guns. I went to a military high school where we were required to pass Army ROTC firearms tests. I qualified as either a “marksman” or an “expert” with every weapon on which we trained. I was also pretty good at archery. Did you know that the New Testament word for “sin” comes from the sport of archery? It’s hamartia, which means “missing the mark”. Aristotle (384-322 BC) borrowed the term and used it in his Poetics to describe the “fatal flaw” in the hero of a dramatic tragedy; the writers of the New Testament then used it to mean “sin”. ~ So, sometimes I don’t see Jesus when I ought to. It’s not that Jesus isn’t there; it’s just that I don’t see him or if I do, like not reacting to the mole fast enough, I don’t recognize him. Like playing “Whack-a-Mole” and failing to hit the rodent, my reaction timing is just not right and I “miss the mark”. I sin by failing to “whack” when Jesus pops up! Therein lies the spiritual discipline to which this text calls me – to look, to recognize, to hone my reaction time, to respond quickly and affirmatively, and (if you’ll pardon some really blatant sacrilege) to Whack-a-Jesus!  The early members of the church were prepared, I think, to be separated from the synagogue, to be cast out from Judaism, and to take the major step of becoming adherents of a new and distinct religion. The church members of the first few centuries were, I think, prepared to be persecuted, killed, martyred. Through their witness and the strength of their faith, the church overcame that separation and that persecution to become the most powerful institution in Western Europe; it was prepared to do that. That was, of course, a mixed blessing and there is a lot of historical debate about and some warranted condemnation of the church’s record as the established religion of empires and kingdoms. However, for 2,000 or so years the church, faced with and prepared for either persecution or power, flourished. ~ What the church was not and still is not prepared for is to be relegated to the sidelines, to be treated with indifference, to be seen as irrelevant to the lives of the people it is charged to reach (I’m thinking “Great Commission” here – Matthew 28:16–20). In other words, the church is not prepared for the contemporary, so-called post-modern world which it, in many ways, has helped to create. A recent book, The Millenials (B&H Books, 2011), claims that 70% of those born between 1980 and 2000 consider the church irrelevant to their lives. Meanwhile,

The early members of the church were prepared, I think, to be separated from the synagogue, to be cast out from Judaism, and to take the major step of becoming adherents of a new and distinct religion. The church members of the first few centuries were, I think, prepared to be persecuted, killed, martyred. Through their witness and the strength of their faith, the church overcame that separation and that persecution to become the most powerful institution in Western Europe; it was prepared to do that. That was, of course, a mixed blessing and there is a lot of historical debate about and some warranted condemnation of the church’s record as the established religion of empires and kingdoms. However, for 2,000 or so years the church, faced with and prepared for either persecution or power, flourished. ~ What the church was not and still is not prepared for is to be relegated to the sidelines, to be treated with indifference, to be seen as irrelevant to the lives of the people it is charged to reach (I’m thinking “Great Commission” here – Matthew 28:16–20). In other words, the church is not prepared for the contemporary, so-called post-modern world which it, in many ways, has helped to create. A recent book, The Millenials (B&H Books, 2011), claims that 70% of those born between 1980 and 2000 consider the church irrelevant to their lives. Meanwhile,  If you’ve been with us here for the services of Maundy Thursday, Good Friday, and Holy Saturday, or have been following the sermons on line, you know that we have come to Act Three of the three-act drama of redemption. In the first act, we saw the protagonist, Jesus of Nazureth, trying one last time make his disciples understand his mission and his message. Through the metaphor of bread and wine, through the enacted parable of foot-washing, through an agonized night of prayer in a garden, he tried to teach them that his was a mission of love and life, but they just didn’t seem to get it. As the curtain fell on Act One, he was being taken away to be questioned by Jewish and Roman authorities and the disciples, frightened and confused, were scattering, unsure of what was going to happen next.

If you’ve been with us here for the services of Maundy Thursday, Good Friday, and Holy Saturday, or have been following the sermons on line, you know that we have come to Act Three of the three-act drama of redemption. In the first act, we saw the protagonist, Jesus of Nazureth, trying one last time make his disciples understand his mission and his message. Through the metaphor of bread and wine, through the enacted parable of foot-washing, through an agonized night of prayer in a garden, he tried to teach them that his was a mission of love and life, but they just didn’t seem to get it. As the curtain fell on Act One, he was being taken away to be questioned by Jewish and Roman authorities and the disciples, frightened and confused, were scattering, unsure of what was going to happen next. Some time in the late Fourth Century, St. John Chrysostom, Archbishop of Constantinople and an important Early Church Father known for his eloquence in preaching and public speaking (hence, the surname Chrysostom which means “golden-mouthed”), preached this sermon on Easter.

Some time in the late Fourth Century, St. John Chrysostom, Archbishop of Constantinople and an important Early Church Father known for his eloquence in preaching and public speaking (hence, the surname Chrysostom which means “golden-mouthed”), preached this sermon on Easter.  Something strange is happening – there is a great silence on earth today, a great silence and stillness. The whole earth keeps silence because the King is asleep. The earth trembled and is still because God has fallen asleep in the flesh and he has raised up all who have slept ever since the world began. God has died in the flesh and hell trembles with fear.

Something strange is happening – there is a great silence on earth today, a great silence and stillness. The whole earth keeps silence because the King is asleep. The earth trembled and is still because God has fallen asleep in the flesh and he has raised up all who have slept ever since the world began. God has died in the flesh and hell trembles with fear. In the beginning he had been tempted by riches, by power, by idolization; all these had been offered in the desert. Now how great the temptation must have been to simply give up! Poet Denise Levertov ponders this allure in her poem Salvator Mundi: Via Crucis

In the beginning he had been tempted by riches, by power, by idolization; all these had been offered in the desert. Now how great the temptation must have been to simply give up! Poet Denise Levertov ponders this allure in her poem Salvator Mundi: Via Crucis In this second act of the drama all that has gone before is recapitulated; all that we saw in yesterday’s first act, the supper in the upper room, the act of servanthood taught there, the agonized prayer in the garden, the willing surrender to unjust authority, and more. Not just yesterday’s first act, but all that has gone before from our first act of defiance in the first garden. Poet Ross Miller reminds us of that bond in his brief verse entitled Tau

In this second act of the drama all that has gone before is recapitulated; all that we saw in yesterday’s first act, the supper in the upper room, the act of servanthood taught there, the agonized prayer in the garden, the willing surrender to unjust authority, and more. Not just yesterday’s first act, but all that has gone before from our first act of defiance in the first garden. Poet Ross Miller reminds us of that bond in his brief verse entitled Tau

A meal is in progress… Is it a seder, the ritual meal of remembrance of the Passover? We don’t really know; the playwrights have not made this clear; the theater critics, the scholars debate this issue. Three of the story-tellers suggest that it is but the fourth, John, tells the tale very differently. (The synoptic gospels tell the story in a similar way and, if truth be told, in the same way – Luke and Matthew based their stories on Mark’s, so to be honest there aren’t three stories, there’s only one that would make us think that this supper is a seder, but John doesn’t. In fact, John doesn’t even care about that – he spends no time at all describing the meal, for him the important thing is what happened afterward, and that comes in a later scene. So as we begin this three-day, three-act drama of redemption, since we have heard Luke’s voice narrating the story, let’s just assume that what we see in this first scene of the first act is, indeed, a seder.)

A meal is in progress… Is it a seder, the ritual meal of remembrance of the Passover? We don’t really know; the playwrights have not made this clear; the theater critics, the scholars debate this issue. Three of the story-tellers suggest that it is but the fourth, John, tells the tale very differently. (The synoptic gospels tell the story in a similar way and, if truth be told, in the same way – Luke and Matthew based their stories on Mark’s, so to be honest there aren’t three stories, there’s only one that would make us think that this supper is a seder, but John doesn’t. In fact, John doesn’t even care about that – he spends no time at all describing the meal, for him the important thing is what happened afterward, and that comes in a later scene. So as we begin this three-day, three-act drama of redemption, since we have heard Luke’s voice narrating the story, let’s just assume that what we see in this first scene of the first act is, indeed, a seder.) The meal is over, the dishes have been cleared. The disciples are arguing among themselves about who is the greater among them. Jesus looks frustrated and troubled; the teachable moment has passed and they clearly have not understood! They just haven’t gotten it.

The meal is over, the dishes have been cleared. The disciples are arguing among themselves about who is the greater among them. Jesus looks frustrated and troubled; the teachable moment has passed and they clearly have not understood! They just haven’t gotten it. “Stay here,” he tells them, “Stay awake while I go over there to pray.” As they settle themselves, he moves away from them, and collapses in a heap, sobbing: “O God … Father, let this pass!”

“Stay here,” he tells them, “Stay awake while I go over there to pray.” As they settle themselves, he moves away from them, and collapses in a heap, sobbing: “O God … Father, let this pass!”