In today’s Gospel lesson we heard, as we always hear on the Second Sunday of Easter Season, the story of “doubting Thomas.” What is striking about the Thomas’s demand … “unless I see” … is that our Lord accepts and encourages it … “Reach out your hand.”

In today’s Gospel lesson we heard, as we always hear on the Second Sunday of Easter Season, the story of “doubting Thomas.” What is striking about the Thomas’s demand … “unless I see” … is that our Lord accepts and encourages it … “Reach out your hand.”

This deceptively simple story is a great encouragement to those of us who follow the Anglican path in Christianity. We have the inheritance of a method of engaging the Faith (and Life) which is described in the work of the seminal Anglican theologian Richard Hooker. Fr. Mike Russell, who has recently published a re-issue of Hooker’s Of the Lawes of Ecclesiastical Polity, describes this method this way:

Anglicans frequently talk about the three-legged stool of authority that distinguishes them from Roman Catholics and Protestants. The former give more authority to Church traditions, the latter to Holy Scripture, but Anglicans somehow add them together and then mix in human reason. Once again, that mixture is Mr. Hooker at work re-framing the discussion. What emerges hardly fits our popular notion of a code of laws and, in fact, we come to understand that in talking about laws, Mr. Hooker is actually speaking throughout about the nature and exercise of authority.[1]

Easter is a joke. Amen.

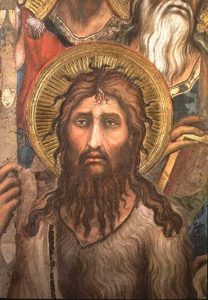

Easter is a joke. Amen. Today marks the beginning of the season we call “Lent,” an old English word which refers to the springtime lengthening of the days. What is this season all about, these forty days (not counting Sundays) during which we are to be, in some way, doing what a hymn attributed to St. Gregory the Great says: “Keep[ing] vigil with our heavenly lord in his temptation and his fast?”

Today marks the beginning of the season we call “Lent,” an old English word which refers to the springtime lengthening of the days. What is this season all about, these forty days (not counting Sundays) during which we are to be, in some way, doing what a hymn attributed to St. Gregory the Great says: “Keep[ing] vigil with our heavenly lord in his temptation and his fast?” A Buddhist tells this story:

A Buddhist tells this story: “In the Name of God the Broken-Hearted. Amen.”

“In the Name of God the Broken-Hearted. Amen.” In the beginning, God said . . . and there is creation.

In the beginning, God said . . . and there is creation. When I was a kid growing up first in southern Nevada and then in southern California, the weeks leading up to Christmas (we weren’t church members so we didn’t call them “Advent”) were always the same. They followed a pattern set by my mother. We bought a tree and decorated it; we set up a model electric train around it. We bought and wrapped packages and put them under the tree, making tunnels for that toy train. We went to the Christmas light shows in nearby parks and drove through the neighborhoods that went all out for cooperative, or sometimes competitive, outdoor displays. My mother would make several batches of bourbon balls (those confections made of crushed vanilla wafers and booze) and give them to friends and co-workers. Christmas Eve we would watch one or more Christmas movies on TV, and early Christmas morning we would open our packages . . . carefully so that my mother could save the wrapping paper. Then all day would be spent cooking and watching TV and playing bridge. After the big Christmas dinner, my step-father and I would do the clean up, my brother and my uncle would watch TV . . . and my mother would sneak off to her room and cry. You see . . . no matter how carefully we prepared, no matter how strictly we adhered to Mom’s pattern, something always went wrong. We never got it right; Christmas never turned out the way my mother wanted it to be.

When I was a kid growing up first in southern Nevada and then in southern California, the weeks leading up to Christmas (we weren’t church members so we didn’t call them “Advent”) were always the same. They followed a pattern set by my mother. We bought a tree and decorated it; we set up a model electric train around it. We bought and wrapped packages and put them under the tree, making tunnels for that toy train. We went to the Christmas light shows in nearby parks and drove through the neighborhoods that went all out for cooperative, or sometimes competitive, outdoor displays. My mother would make several batches of bourbon balls (those confections made of crushed vanilla wafers and booze) and give them to friends and co-workers. Christmas Eve we would watch one or more Christmas movies on TV, and early Christmas morning we would open our packages . . . carefully so that my mother could save the wrapping paper. Then all day would be spent cooking and watching TV and playing bridge. After the big Christmas dinner, my step-father and I would do the clean up, my brother and my uncle would watch TV . . . and my mother would sneak off to her room and cry. You see . . . no matter how carefully we prepared, no matter how strictly we adhered to Mom’s pattern, something always went wrong. We never got it right; Christmas never turned out the way my mother wanted it to be. This is a special Sunday for me. Friday marked the 28th anniversary of my ordination as a priest in the Episcopal Church. It was on Sunday, June 23, 1991, that I celebrated my first mass. So I am grateful to you and to Fr. George for the privilege of an altar at which to celebrate the Holy Mysteries and a pulpit from which to preach the gospel on this, my anniversary Sunday.

This is a special Sunday for me. Friday marked the 28th anniversary of my ordination as a priest in the Episcopal Church. It was on Sunday, June 23, 1991, that I celebrated my first mass. So I am grateful to you and to Fr. George for the privilege of an altar at which to celebrate the Holy Mysteries and a pulpit from which to preach the gospel on this, my anniversary Sunday. There is an old tradition in the church: on Trinity Sunday, rectors do their best to get someone else to preach. If they have a curate or associate priest, he or she gets the pulpit on that day. If not, they try to invite some old retired priest to fill in (as Father George has done today). No one really wants to preach on Trinity Sunday, the only day of the Christian year given to the celebration or commemoration of a theological doctrine, mostly because theology is dull, dry, and boring to most people and partly because this particular theology is one most of us get wrong no matter how much we try to do otherwise. Back when I was a curate getting the Trinity Sunday assignment, my rector encouraged me with the sunny observation that, listening to a sermon in almost any church on Trinity Sunday, one could be practically guaranteed to hear heresy.

There is an old tradition in the church: on Trinity Sunday, rectors do their best to get someone else to preach. If they have a curate or associate priest, he or she gets the pulpit on that day. If not, they try to invite some old retired priest to fill in (as Father George has done today). No one really wants to preach on Trinity Sunday, the only day of the Christian year given to the celebration or commemoration of a theological doctrine, mostly because theology is dull, dry, and boring to most people and partly because this particular theology is one most of us get wrong no matter how much we try to do otherwise. Back when I was a curate getting the Trinity Sunday assignment, my rector encouraged me with the sunny observation that, listening to a sermon in almost any church on Trinity Sunday, one could be practically guaranteed to hear heresy. Lenten Journal, Day 21

Lenten Journal, Day 21