I think it’s no secret that I am a news junkie. I read several articles and opinion pieces in three major newspapers (the N.Y. Times, the Washington Post, and the Manchester Guardian) everyday. I watch the cable news commentaries on all of the news channels (yes, even Fox) and I read a couple of major international journals on a regular basis (the Economist and Foreign Policy).

I’ve been a news junkie since I was a kid. It was not uncommon for my parents and me (and my older brother when he was still living with us) to watch the CBS Evening News during dinner. I will always remember Walter Cronkite’s sign off: “And that’s the way it is . . . . ” and then he would say the date. “And that’s the way it is November 5, 2017.” Over on NBC, which my grandparents preferred to watch, Chet Huntley and David Brinkley shared the anchorman job, one in Washington, DC, the other in New York City, and they would sign off by wishing each other and the nation “Good Night!” There was something reassuring about those sign-offs, something solid and final. If Uncle Walter said, “That’s the way it is . . . .” If Chet and David said, “Good night!” we could rest easy knowing that the world was right, that the facts were nailed down.

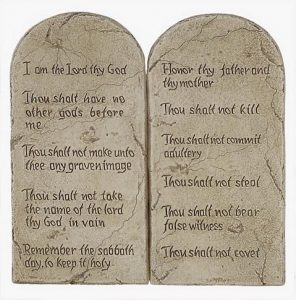

A lawyer asked Jesus a question to test him. “Teacher, which commandment in the law is the greatest?” He said to him, “’You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your mind.’ This is the greatest and first commandment. And a second is like it: ‘You shall love your neighbor as yourself.’ On these two commandments hang all the law and the prophets.”

A lawyer asked Jesus a question to test him. “Teacher, which commandment in the law is the greatest?” He said to him, “’You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your mind.’ This is the greatest and first commandment. And a second is like it: ‘You shall love your neighbor as yourself.’ On these two commandments hang all the law and the prophets.” As I pondered our scriptures for today I was struck by how different, how utterly foreign, one might most accurately use the word “alien,” the social landscape of the bible is from our own. We, children of a post-Enlightenment Constitution which makes a clear delineation, almost a compartmentalization, between the civic and the religious, simply cannot quickly envision the extent to which those areas of human existence were entangled and intertwined for those who wrote and whose lives are described in both the Old and New Testaments. I tried to think of an easy metaphor to help illustrate the difference between our worldview and that of either the ancient wandering Hebrews represented by Moses in the lesson from Exodus or of the first Century Palestinians and Romans characterized by Jesus, the temple authorities, and Paul.

As I pondered our scriptures for today I was struck by how different, how utterly foreign, one might most accurately use the word “alien,” the social landscape of the bible is from our own. We, children of a post-Enlightenment Constitution which makes a clear delineation, almost a compartmentalization, between the civic and the religious, simply cannot quickly envision the extent to which those areas of human existence were entangled and intertwined for those who wrote and whose lives are described in both the Old and New Testaments. I tried to think of an easy metaphor to help illustrate the difference between our worldview and that of either the ancient wandering Hebrews represented by Moses in the lesson from Exodus or of the first Century Palestinians and Romans characterized by Jesus, the temple authorities, and Paul. “The kingdom of heaven may be compared to a king . . . .”

“The kingdom of heaven may be compared to a king . . . .”  I’m wearing an orange stole today and a couple of you asked me on the way into church, “What season is orange?” Well, it’s not a seasonal stole … although I suppose we could say it commemorates the season of unregulated and out of control gun violence. A few years ago, a young woman named Hadiya Pendleton was shot and killed in Chicago; her friends began wearing orange, like hunters wear for safety, in her honor on her birthday in June. A couple of years ago, Bishops Against Gun Violence, an Episcopal group, became a co-sponsor of Wear Orange Day and some of us clergy here in Ohio decided to make and wear orange stoles on the following Sunday. Our decision got press notice and spread to clergy of several denominations all over the country.

I’m wearing an orange stole today and a couple of you asked me on the way into church, “What season is orange?” Well, it’s not a seasonal stole … although I suppose we could say it commemorates the season of unregulated and out of control gun violence. A few years ago, a young woman named Hadiya Pendleton was shot and killed in Chicago; her friends began wearing orange, like hunters wear for safety, in her honor on her birthday in June. A couple of years ago, Bishops Against Gun Violence, an Episcopal group, became a co-sponsor of Wear Orange Day and some of us clergy here in Ohio decided to make and wear orange stoles on the following Sunday. Our decision got press notice and spread to clergy of several denominations all over the country.  Authority. The authority of Jesus Christ is what Paul writes about in the letter to the Philippians, in which he quotes a liturgical hymn sung in the early Christian communities:

Authority. The authority of Jesus Christ is what Paul writes about in the letter to the Philippians, in which he quotes a liturgical hymn sung in the early Christian communities: Sweet Holy Spirit, sweet heavenly dove,

Sweet Holy Spirit, sweet heavenly dove, Recovery. It’s what they call the process that comes after surgery. A physician cuts you open, spends a few minutes or hours doing whatever needs to be done, sews (or staples or glues) you up, and they wheel you out of the surgical theater and into the recovery room. Recovery has started, but when you leave the recovery room it isn’t over. It goes on and on for days, weeks, even months.

Recovery. It’s what they call the process that comes after surgery. A physician cuts you open, spends a few minutes or hours doing whatever needs to be done, sews (or staples or glues) you up, and they wheel you out of the surgical theater and into the recovery room. Recovery has started, but when you leave the recovery room it isn’t over. It goes on and on for days, weeks, even months. When I told friends, colleagues, and parishioners I was contemplating a total knee replacement, the singular piece of consistent advice was, “Do the exercises! Keep up with the therapy!” The surgeon who was to do the deed gave me a booklet full of pre-operative exercises to do at least twice each day; that seemed doable and it was – twice a day for six weeks before surgery.

When I told friends, colleagues, and parishioners I was contemplating a total knee replacement, the singular piece of consistent advice was, “Do the exercises! Keep up with the therapy!” The surgeon who was to do the deed gave me a booklet full of pre-operative exercises to do at least twice each day; that seemed doable and it was – twice a day for six weeks before surgery. A Facebook friend posted a meme recently featuring the word hiraeth. That’s not a word one hears or sees very often. It’s Welsh and has no direct English equivalent. Pronounced “hear-eye’th,” it refers to a sense of nostalgia for a lost home, the sort of home you can’t ever go back to, an unquenchable homesickness.

A Facebook friend posted a meme recently featuring the word hiraeth. That’s not a word one hears or sees very often. It’s Welsh and has no direct English equivalent. Pronounced “hear-eye’th,” it refers to a sense of nostalgia for a lost home, the sort of home you can’t ever go back to, an unquenchable homesickness.