====================

A homily offered by the Rev. Dr. C. Eric Funston on the Twelfth Sunday after Pentecost, August 7, 2016, to the people of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Medina, Ohio, where Fr. Funston is rector.

(The lessons for the day are Proper 14C of the Revised Common Lectionary: Genesis 15:1-6; Psalm 33:12-22; Hebrews 11:1-3,8-16; and St. Luke 12:32-40. These lessons may be found at The Lectionary Page.)

====================

In your bulletins this week, I have added three pictures to illustrate this sermon. These pictures kept coming back to mind as I read and re-read the lessons. The pictures are as follows:

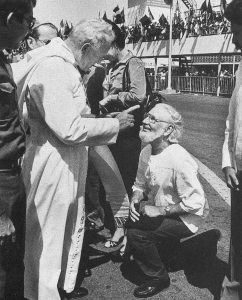

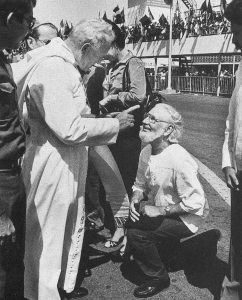

- A photograph of Pope John Paul II’s arrival in Managua, Nicaragua, on July 5, 1983. Fr. Ernesto Cardenal, who served in the Nicaraguan government as Minister of Culture, kneels before the Pope who is wagging his finger at him.

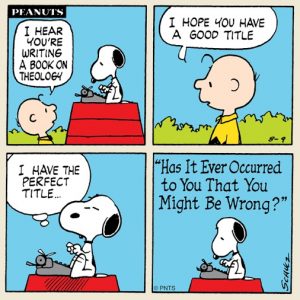

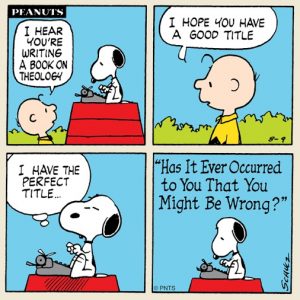

- One of my favorite cartoons, a four-panel Peanuts offering first published on August 9, 1976, in which the beagle Snoopy is writing a book of theology with the planned title “Has It Ever Occurred to You That You Might Be Wrong?”

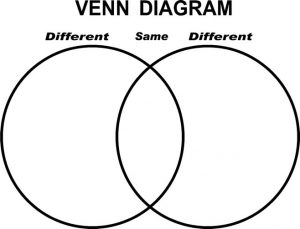

- A generic Venn diagram

I will refer to these pictures later in the sermon.

Most exegeses of today’s Genesis text focus on the last sentence, “And [Abraham] believed the Lord; and the Lord reckoned it to him as righteousness,” and treat this story as one of faith. But, in all honesty, this is a story of doubt. It is the story of Abraham questioning God’s promise of a posterity; it is a story of tribalism and concern for bloodline, ethnicity, and inheritance.

We humans have a predisposition to tribalism, to congregating in social groupings of similar people. I was at a continuing education event this week in which one of the exercises explored the issue of economic segregation in our society; the facilitator asked each of us to describe the home in which we live and the neighborhood and community within which it is situated. One of the uniform characteristics was that no matter what our race or ethnic type might have been, our home neighborhoods were made up of people for the most part similar to ourselves. We in modern 21st Century America may not consciously organize ourselves into tribal groupings, but if we take time to look at ourselves honestly we will find that we do: like attracts like. As individuals we initially, we situate ourselves within nuclear families, then as we grow we broaden our social interactions to extended families, then clan, tribe, ethnic group, nation . . . .

This has been so from the beginning of time. Those of us who accept the notion of natural selection and evolution can look at our nearest genetically similar relatives, the apes and chimpanzees, and see this family and clan predilection. Those of us who accept the notion of divine handiwork can look to our traditional religious literature and see it in the stories of creation and God’s interactions with this chosen people. Today’s lesson from Genesis is a case in point.

God has chosen Abram, an elderly, childless man in the city of Ur to be “God’s guy,” so to speak. God has promised Abram that he will be the father of nations; in fact, God changes Abram’s name to “Abraham” which means “father of a multitude.” It is not, however, clear to Abraham how this will happen . . . and at the time of our reading, it hasn’t happened and Abraham is getting anxious. He challenges God with this very tribal sort of concern: “Who will inherit my estate? Will it be this slave, Eliezer of Damascus?”

Although our New Revised Standard version translates the ambiguous Hebrew to describe Eliezer as “a slave born in my house,” there is considerable scholarly debate over whether that is the meaning of the Hebrew text. Why would Eliezer be described as “of Damascus” if he had been born in Abraham’s home? The New International Version renders the description as “a servant in my household,” which is probably the better reading. Eliezer, rather than being a native of Abraham’s domestic unit, is from another city, Damascus, from another clan, another tribe, perhaps even a different ethnic group . . . yet according to the custom of the time, he would inherit his master’s fortune were Abraham to die childless. This is rank tribalism.

God’s response to Abraham’s challenge is to take Abraham outside and show him the stars and ask him, “Has it ever occurred to you that you might be wrong?” Well, God doesn’t, actually . . . but that’s what it boils down to. God’s response to Abraham is, “Thank again!”

God’s response to Abraham’s challenge is to take Abraham outside and show him the stars and ask him, “Has it ever occurred to you that you might be wrong?” Well, God doesn’t, actually . . . but that’s what it boils down to. God’s response to Abraham is, “Thank again!”

Many social scientists today use the word “tribalism” to describe the fracturing of our society. The economist Robert Reich, for example, wrote an essay two and a half years ago entitled Tribalism Is Tearing America Apart. In it, Dr. Reich wrote:

America’s new tribalism can be seen most distinctly in its politics. Nowadays the members of one tribe . . . hold sharply different views and values than the members of the other . . . .

Each tribe has contrasting ideas about rights and freedoms . . . Each has its own totems . . . and taboos . . . . Each, its own demons . . . ; its own version of truth . . . ; and its own media that confirm its beliefs.

Five years ago, writer Wade Shepherd asserted, “The new tribal lines of America are not based on skin color, creed, geographic origin, or ethnicity, but on opinion, political position, and world view.” In other words, where Abraham’s tribalist concern (and subsequently that of the Old Testament Law) was about bloodline and ethnic purity, in the modern world our tribalist tendency centers on ideology and philosophical purity. As Shepherd put it, people “are selecting a singular point of view and isolating themselves within its barricade.” (The New American Tribalism) And although Reich and Shepherd were looking specifically at the situation in the U.S., their observations are valid around the world and have been for some time.

When Pope John Paul II scolded Fr. Cardenal upon the his arrival in Nicaragua, it was because Cardenal had collaborated with the Marxist Sandinistas and, after the Sandinista victory in 1979, he became their government’s Minister of Culture. His brother, Fr. Fernando Cardenal S.J. also worked with the Sandinista government in the Ministry of Education, directing a successful literacy campaign. There were a handful of other priests working in the government, as well.

When Pope John Paul II scolded Fr. Cardenal upon the his arrival in Nicaragua, it was because Cardenal had collaborated with the Marxist Sandinistas and, after the Sandinista victory in 1979, he became their government’s Minister of Culture. His brother, Fr. Fernando Cardenal S.J. also worked with the Sandinista government in the Ministry of Education, directing a successful literacy campaign. There were a handful of other priests working in the government, as well.

They were all influenced by a school of thought called “liberation theology” which taught, among other things, that Christians could work alongside of non-Christians, even atheists, on the shared the goal of improving the lives of the poor. As Leonardo and Clodovis Boff, theologians from Brazil, put it, “The Church has the duty to act as agent of liberation.” (Salvation and Liberation, Robert R. Barr, trans., Orbis Books:New York: 1984)

The pope, however, with his personal background in Communist Poland, was intolerant of liberation theology and forbade Cardenal and the others to be involved in the Sandinista government. Ernesto Cardenal ignored this order, and thus the finger-wagging rebuke. Eventually, in February 1984 John Paul defrocked Cardenal because of his liberation theology, but that decision was overturned 30 years later in August 2114 by the current Pope Francis.

The picture thus illustrates for me the kind of tribalist insistence on ideological purity that is our modern equivalent of Abraham’s challenge to God. God’s response to Abraham’s tribalism was essentially, “Think again!” And God’s response to our tribalism, to our insistence on our own ideas, our own totems, our own demons, our own versions of the truth, is the same; it’s Snoopy’s question, “Has it ever occurred to you that you might be wrong?”

Which brings me to the reading from the Letter to the Hebrews and, especially, its first sentence which defines what faith is: “Faith is the assurance of things hoped for, the conviction of things not seen.” The rest of the lesson betrays why it was chosen in the lectionary; it exegetes the story of Abraham’s faith – the faith which came after the challenge of his doubt, after God had answered his tribalist concern about bloodlines and ethnicity and inheritance. But it’s that first sentence, the definition of faith that I think is the important part for us to consider.

The first part of the definition says faith is “the assurance of things hoped for.” The word translated as “assurance” is the Greek word hypostasis, a compound word – hypo meaning “under” and stasis meaning “to stand” – thus an “under standing.” But not in the sense of intellectual comprehension, rather in the literal, physical sense of something that “stands under,” that is foundational or bedrock. Thus, hypostasis “is something basic, something solid, something firm;” it “provides a place to stand from which one can hope.” (Amy L.B. Peeler, Wheaton College)

In one of the exercises at the continuing education seminar I was at this week we were given a large sheet of drawing paper and asked to draw a map or picture of our personal spiritual growth with a focus on that which provides stability in our lives, and then to describe our artwork to the group. Of course, nearly all of us attempted to depict God as the stable center, or unchanging goal or beginning, the whatever of our spiritual journeys, but one participant didn’t do that. In fact, he didn’t draw anything at all on his paper before standing in front of the group. He drew some squiggles and boxes and whatever on the sheet as he described his spiritual autobiography, but then said, “What is stable in all of this is the paper!” Brilliant! The paper represented the hypostasis, the bedrock standing under his life, the foundation of faith on which the details played out and changed and developed over time, and that is really true for all of us.

The second part of the definition is that faith is “the conviction of things not seen.” We hear that word “conviction” as synonymous with “belief” or “firm opinion,” but the Greek original, elegchos, carries the sense of “proof” or “evidence” such as would be presented in a court of law, such as would be used to convict a defendant in the dock. Faith is the evidence which establishes the existence of that which cannot be seen, the proof that there is an invisible foundation for one’s life, one’s beliefs and opinions, one’s actions. “What is stable in all of this is the paper!”

Our modern ideological tribalism insists that everyone in the tribe have the same life, the same beliefs, the same opinions, and undertake the same actions, but more than that it insists that anyone who differs to any significant degree in any of those things is outside the tribe. If we were to draw the tribes as circles on that sheet of paper, ideological tribalism insists that each tribe is a circle that does not even touch another, and yet we all know that that’s simply not true.

We know that if there are tribal circles on that foundational paper, they are more like the circles on a Venn diagram, not only touching but overlapping. That was true of the ancient Hebrews; their tribalism might demand ethnic purity, but they never achieved it; the Old Testament demonstrates that, again and again! Modern ideological tribalism is no different. Ideologies, religious beliefs, political opinions differ in many ways, but in many others they share much in common; they overlap. People’s lives and opinions overlap, but ideological tribalism encourages us to hear only the differing opinions and blinds us to our similar lives.

We know that if there are tribal circles on that foundational paper, they are more like the circles on a Venn diagram, not only touching but overlapping. That was true of the ancient Hebrews; their tribalism might demand ethnic purity, but they never achieved it; the Old Testament demonstrates that, again and again! Modern ideological tribalism is no different. Ideologies, religious beliefs, political opinions differ in many ways, but in many others they share much in common; they overlap. People’s lives and opinions overlap, but ideological tribalism encourages us to hear only the differing opinions and blinds us to our similar lives.

During the Republican National Convention in Cleveland a man named Benjamin Mathes sat outside the convention center with a sign reading “Free Listening.” His goal was to engage convention goers on a personal level, to hear without judgment what they had to say about controversial topics. He was mostly disappointed, but on the Urban Confessional website he related listening to a woman who had a strong opinion on topic about which he disagreed vehemently.

He was asked, “How do you listen to someone with whom you disagree?” His answer is instructive: “It takes a lot of forgiveness, compassion, patience, and courage to listen in the face of disagreement. I could write pages on each of these principles, but let’s start with the one thing that makes forgiveness, compassion, patience, and courage possible. We must work to hear the person not just the opinion.” He then quoted the Christian rapper David Sherer who performs under the stage name Agape. In one of his pieces Agape sings, “Hear the biography, not the ideology.”

Mathes continues, “When someone has a point of view we find difficult to understand, disagreeable, or even offensive, we must look to the set of circumstances that person has experienced that resulted in that point of view. Get their story, their biography, and you’ll open up the real possibility of an understanding that transcends disagreement.”

Which brings me to today’s gospel lesson in which Jesus admonishes us to be like servants who keep their lamps lit for their master on his wedding night. I suspect that most people who hear this admonition are reminded of the parable of the five wise and five foolish bridesmaids, but this week what I remembered was Jesus command in Matthew’s Gospel, “Let your light shine before others, so that they may see your good works and give glory to your Father in heaven.” (Mt 5:16)

The purpose of the lit lamps is not simply to have lit lamps! It is to have light by which something can be done, something can be seen. The purpose of the servants’ lamps is to light the way for the bride and bridegroom, to illuminate the pathway and allow them to see the door. The purpose of keeping our lamps lit is so that people may see our “good works and give glory to [our] Father in heaven.” It is our works, our lives and actions, which matter, not our ideologies, or religious beliefs, or political opinions.

That was the point of Fr. Cardenal’s theology and belief that as a Christian he could work with Marxists, with atheists to improve the lives of the poor in Nicaragua. He saw the overlap of their circles on the political Venn diagram. Their ideologies differed, but their goals, their actions and works in regard to the poor, the point where their circles overlapped, did not. Underlying it all was the foundational bedrock of things hoped for, the evidence of things not yet seen. The pope apparently could not see that overlap; his disciplining of Fr. Cardenal and other Latin American priests came out of modern ideological tribalism, an insistence on purity of belief which made it impossible to work toward a common goal with someone of a differing opinion. Our modern American ideological tribalism is doing the same thing to us.

I look at that picture and just wish that someone, God or Snoopy or anyone, might have stepped in and just whispered in his Holiness’s ear, “Has it ever occurred to you that you might be wrong?” My prayer is that God might whisper that in everyone’s ears from time to time. It might shine some light on our ever changing Venn diagrams of ideological tribalism; it might remind us that the diagrams, the circles on the paper, move all the time and that “what is stable in all this is the paper,” the foundational bedrock, the “assurance of things hoped for, the conviction of things not seen.” Amen.

====================

A request to my readers: I’m trying to build the readership of this blog and I’d very much appreciate your help in doing so. If you find something here that is of value, please share it with others. If you are on Facebook, “like” the posts on your page so others can see them. If you are following me on Twitter, please “retweet” the notices of these meditations. If you have a blog of your own, please include mine in your links (a favor I will gladly reciprocate). Many thanks!

====================

Father Funston is the rector of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Medina, Ohio.

Our first lesson today is from a book with the wholly amazing title The Book of the All-Virtuous Wisdom of Joshua ben Sira, usually (and mercifully) shortened to Sirach. It is accepted as part of the Christian biblical canon by Roman Catholics, the Eastern Orthodox, and most of the Oriental Orthodox churches. In our Anglican tradition, it is not accepted as canonical, but we do read it “for example of life and instruction of manners;” however, it cannot be used to establish any doctrine. (Article VI of the Articles of Religion, 1801) The book is in the tradition known as “wisdom literature;” basically, it is a collection of ethical teachings closely resembling the canonical Book of Proverbs, and serving the same function.

Our first lesson today is from a book with the wholly amazing title The Book of the All-Virtuous Wisdom of Joshua ben Sira, usually (and mercifully) shortened to Sirach. It is accepted as part of the Christian biblical canon by Roman Catholics, the Eastern Orthodox, and most of the Oriental Orthodox churches. In our Anglican tradition, it is not accepted as canonical, but we do read it “for example of life and instruction of manners;” however, it cannot be used to establish any doctrine. (Article VI of the Articles of Religion, 1801) The book is in the tradition known as “wisdom literature;” basically, it is a collection of ethical teachings closely resembling the canonical Book of Proverbs, and serving the same function. Our reading from the Book of Isaiah today is the second half of chapter 58, a chapter which begins with God ordering the prophet to “Shout out,” to “do not hold back,” to “lift up [his] voice like a trumpet” with God’s answer to a question asked by the people of Jerusalem: “Why do we fast, but you do not see? Why humble ourselves, but you do not notice?” (Isaiah 58:1,3a)

Our reading from the Book of Isaiah today is the second half of chapter 58, a chapter which begins with God ordering the prophet to “Shout out,” to “do not hold back,” to “lift up [his] voice like a trumpet” with God’s answer to a question asked by the people of Jerusalem: “Why do we fast, but you do not see? Why humble ourselves, but you do not notice?” (Isaiah 58:1,3a) In philosophy and theology there is an exercise named by the Greek word deiknumi. The word simply translated means “occurrence” or “evidence,” but in philosophy it refers to a “thought experiment,” a sort of meditation or exploration of a hypothesis about what might happen if certain facts are true or certain situations experienced. It’s particularly useful if those situations cannot be replicated in a laboratory or if the facts are in the past or future and cannot be presently experienced. St. Paul uses the word only once in his epistles: in the last verse of chapter 12 of the First Letter to the Corinthians, he uses the verbal form when he admonishes his readers to “strive for the greater gifts. And I will show you [deiknuo, ‘I will give you evidence of’] a still more excellent way.” It is the introduction to his famous treatise on agape, divine love, a thought experiment (if you will) about the best expression, the “still more excellent” expression of the greatest of the virtues.

In philosophy and theology there is an exercise named by the Greek word deiknumi. The word simply translated means “occurrence” or “evidence,” but in philosophy it refers to a “thought experiment,” a sort of meditation or exploration of a hypothesis about what might happen if certain facts are true or certain situations experienced. It’s particularly useful if those situations cannot be replicated in a laboratory or if the facts are in the past or future and cannot be presently experienced. St. Paul uses the word only once in his epistles: in the last verse of chapter 12 of the First Letter to the Corinthians, he uses the verbal form when he admonishes his readers to “strive for the greater gifts. And I will show you [deiknuo, ‘I will give you evidence of’] a still more excellent way.” It is the introduction to his famous treatise on agape, divine love, a thought experiment (if you will) about the best expression, the “still more excellent” expression of the greatest of the virtues.

God’s response to Abraham’s challenge is to take Abraham outside and show him the stars and ask him, “Has it ever occurred to you that you might be wrong?” Well, God doesn’t, actually . . . but that’s what it boils down to. God’s response to Abraham is, “Thank again!”

God’s response to Abraham’s challenge is to take Abraham outside and show him the stars and ask him, “Has it ever occurred to you that you might be wrong?” Well, God doesn’t, actually . . . but that’s what it boils down to. God’s response to Abraham is, “Thank again!” When Pope John Paul II scolded Fr. Cardenal upon the his arrival in Nicaragua, it was because Cardenal had collaborated with the Marxist Sandinistas and, after the Sandinista victory in 1979, he became their government’s Minister of Culture. His brother, Fr. Fernando Cardenal S.J. also worked with the Sandinista government in the Ministry of Education, directing a successful literacy campaign. There were a handful of other priests working in the government, as well.

When Pope John Paul II scolded Fr. Cardenal upon the his arrival in Nicaragua, it was because Cardenal had collaborated with the Marxist Sandinistas and, after the Sandinista victory in 1979, he became their government’s Minister of Culture. His brother, Fr. Fernando Cardenal S.J. also worked with the Sandinista government in the Ministry of Education, directing a successful literacy campaign. There were a handful of other priests working in the government, as well.  We know that if there are tribal circles on that foundational paper, they are more like the circles on a Venn diagram, not only touching but overlapping. That was true of the ancient Hebrews; their tribalism might demand ethnic purity, but they never achieved it; the Old Testament demonstrates that, again and again! Modern ideological tribalism is no different. Ideologies, religious beliefs, political opinions differ in many ways, but in many others they share much in common; they overlap. People’s lives and opinions overlap, but ideological tribalism encourages us to hear only the differing opinions and blinds us to our similar lives.

We know that if there are tribal circles on that foundational paper, they are more like the circles on a Venn diagram, not only touching but overlapping. That was true of the ancient Hebrews; their tribalism might demand ethnic purity, but they never achieved it; the Old Testament demonstrates that, again and again! Modern ideological tribalism is no different. Ideologies, religious beliefs, political opinions differ in many ways, but in many others they share much in common; they overlap. People’s lives and opinions overlap, but ideological tribalism encourages us to hear only the differing opinions and blinds us to our similar lives. Some translations of the Bible like to add to it. They insert explanatory headings and titles into the teachings of the authors of scripture or before the parables or important elements in Jesus’ life and teachings. The New International Version, for example, adds the title “The Parable of the Rich Fool” to our gospel text for today. It breaks up our reading from Ecclesiastes with three such headings: “Everything Is Meaningless,” “Wisdom Is Meaningless,” and “Toil Is Meaningless.” If you have a bible like that, take those titles and subheadings with a very large grain of salt because they are simply not accurate!

Some translations of the Bible like to add to it. They insert explanatory headings and titles into the teachings of the authors of scripture or before the parables or important elements in Jesus’ life and teachings. The New International Version, for example, adds the title “The Parable of the Rich Fool” to our gospel text for today. It breaks up our reading from Ecclesiastes with three such headings: “Everything Is Meaningless,” “Wisdom Is Meaningless,” and “Toil Is Meaningless.” If you have a bible like that, take those titles and subheadings with a very large grain of salt because they are simply not accurate! When I was practicing law and serving as the chief legal officer of the Episcopal Diocese of Nevada, there was a church member (of another congregation than mine) who always greeted me with a lawyer story. “What’s the difference between a lawyer and ….? ” “There was a lawyer who went to heaven ….” I think I’ve heard all the lawyer jokes, and I considered starting with one this morning. If I had had more than a passing acquaintance with Jim McKee, I might have done so. But I didn’t know Jim, so I won’t do that. Instead, I’ll begin with some poetry.

When I was practicing law and serving as the chief legal officer of the Episcopal Diocese of Nevada, there was a church member (of another congregation than mine) who always greeted me with a lawyer story. “What’s the difference between a lawyer and ….? ” “There was a lawyer who went to heaven ….” I think I’ve heard all the lawyer jokes, and I considered starting with one this morning. If I had had more than a passing acquaintance with Jim McKee, I might have done so. But I didn’t know Jim, so I won’t do that. Instead, I’ll begin with some poetry. St. Paul’s Parish hosted the weekly “ice cream social” that accompanied the Community Band Concerts on Friday evening on the Town Square during summer. We’ve done this before although not for a few years (we tried for three years running to be host, but each Friday we were assigned during those years there was a thunderstorm and the event was rained out).

St. Paul’s Parish hosted the weekly “ice cream social” that accompanied the Community Band Concerts on Friday evening on the Town Square during summer. We’ve done this before although not for a few years (we tried for three years running to be host, but each Friday we were assigned during those years there was a thunderstorm and the event was rained out).  Sometime during the summer of 1969 (for the life of me, I can’t recall exactly when) and again in August of 1973, I was privileged to walk along the Promenade des Anglais on the Mediterranean waterfront of Nice. I was very young (or so I now consider myself to have been) and, on that second occasion, very much in love (or so I then considered myself) with a young French woman named Josienne. We quickly lost touch when that summer and my time as a student at the Sorbonne came to an end, but I have always fondly remembered her. Nice was her home town and, I suspect, is probably her home now. And I wonder, now, where she was on the evening of Bastille Day 2016. I pray she was not on the Promenade.

Sometime during the summer of 1969 (for the life of me, I can’t recall exactly when) and again in August of 1973, I was privileged to walk along the Promenade des Anglais on the Mediterranean waterfront of Nice. I was very young (or so I now consider myself to have been) and, on that second occasion, very much in love (or so I then considered myself) with a young French woman named Josienne. We quickly lost touch when that summer and my time as a student at the Sorbonne came to an end, but I have always fondly remembered her. Nice was her home town and, I suspect, is probably her home now. And I wonder, now, where she was on the evening of Bastille Day 2016. I pray she was not on the Promenade.