====================

A sermon offered on the Sunday after the Ascension, the Seventh Sunday of Easter, May 17, 2015, to the people of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Medina, Ohio, where Fr. Funston is rector.

(The lessons for the day are Acts 1:15-17,21-26; Psalm 1; 1 John 5:9-13; and John 17:6-19. These lessons can be read at The Lectionary Page.)

====================

“That they may be one, as we are one.” (Jn 17:11)

“That they may be one, as we are one.” (Jn 17:11)

Obviously, there is quite a bit more to the “Farewell Discourse” or “High Priestly Prayer” of which today’s gospel lesson is a part, but in the end (I believe) the central petition of Jesus’ last prayer is one for the unity of the church and for God the Father’s protection of that unity.

Perhaps 60 or 70 years had passed since Jesus’ death, resurrection, and ascension when the author or authors of the Fourth Gospel put the finishing touches on this manuscript. Bible historians believe this gospel was written in Roman Asia (what is now Turkey), perhaps in the city of Ephesus, almost 1,100 miles from Jerusalem by land (over 600 miles by sea), sometime between 90 and 100 A.D.

They wrote not from personal experience and witness, but from oral tradition crossing decades of theological development and a great distance of cultural difference. There were many things that they had heard that Jesus had said, and a great deal that they needed Jesus to have said, and when they reached almost the end of their story, they had him say a lot of it in this Farewell Discourse.

Guided (we believe) by the Holy Spirit, the authors of this gospel portray Jesus offering this lengthy prayer to the Father, a prayer which might also be thought of as his last theological instruction to his inner circle, those who came to be called “The Apostles.” At its core is his wish that they stick together, “that they may be one, as we are one,” and that they continue his ministry by teaching the Truth he had sought to teach them.

The Episcopal Church takes this call to unity and ministry seriously, understanding it as a call not to uniformity but to harmony. In 2009, the 76th General Convention of the Episcopal Church declared that a “Biblically-based respect for the diversity of understandings that authentic, truth-seeking human beings have is essential for communal reasoning and faithful living. The revelation of God in Christ calls us therefore to participate in our relationship with God and one another in a manner that is at once faithful, loving, lively, and reasonable. This understanding continues to call Episcopalians to find our way as one body through various conflicts. It is not a unity of opinion or a sameness of vision that holds us together. Rather, it is the belief that we are called to walk together in Jesus’ path of reconciliation not only through our love for the other, but also through our respect for the legitimacy of the reasoning of the other. Respect for reason empowers us to meet God’s unfolding world as active participants in the building of the Kingdom and to greet God’s diverse people with appropriate welcome and gracious hospitality.” (Interreligious Relation Statement – Final Text)

Last Sunday, fifteen members of our congregation, joined by two others from St. Patrick in Brunswick, knelt before Bishop William Persell and, in some manner, reaffirmed the covenant made at their baptism. One was already a confirmed Episcopalian; two were teenagers who’d grown up in this parish. The others came to us from a variety of backgrounds, some actively Christian in other traditions, some not. Whatever their background, however, those fifteen persons apparently found here at St. Paul’s Parish that “appropriate welcome and gracious hospitality,” that unity in ministry to which the High Priestly Prayer compels us.

In his prayer, Jesus refers to his disciples (all of them, not just the Apostles) as “those whom [the Father] gave me from the world.” (v. 6) Earlier during their dinner conversation, he had reminded his followers, “You did not choose me but I chose you.” (Jn 15:16a) We tend to think otherwise of our membership in this or any church; we like to believe that we are autonomous, that we are here by our own decision, and our confirmation service certainly encourages our thinking in that direction.

In that liturgy, the Bishop asks the candidates, “Do you renew your commitment to Jesus Christ?” and they answer, “I do, and with God’s grace I will follow him as my Savior and Lord.” (BCP 1979, page 415) We tend to focus on only the first two words of that response, “I do.” But Jesus’ words at the Last Supper compel us to surrender our autonomy and hear clearly the rest of the answer: “I do … with God’s grace ….”

“I do … with God’s grace ….”

Let’s consider the case of Matthias chosen as replacement Apostle in our reading from the Book of Acts. Peter, having heard Christ’s prayer that the unity of the church might be preserved, knew that Jesus’ plan of a leadership group of twelve followers had to be reconstituted; the unity for which Jesus had prayed had been broken and needed to be restored. “One of these [who have been with us from the beginning] must become a witness with us to [the Lord’s] resurrection.” (Acts 1:21) Peter was well aware that Jesus’ mission had been to restore Israel and that this inner circle was key to that mission; he probably recalled that Jesus had told them that they would “sit on twelve thrones, judging the twelve tribes of Israel” (Mt 19:28), something that could not happen if there were only eleven of them. To restore the embryonic church to its original unity, a replacement apostle was needed.

Two candidates meeting the community’s qualifications are put forward, Matthias and another named Justus, and Matthias is chosen through the casting of lots. It might seem that this is all just a game of chance, but that is not so. Consider what has happened here: the action is taken by the apostles as a group; before casting the lots, the group has studied the Scriptures, prayed together, and discussed what they were about to do. The decision was not that of the leadership only; it clearly was one concurred in by the entire congregation present (about one-hundred and twenty we are told). And one scholar has suggested that there may have been some sort of group affirmation after the lots were cast, as is implied by the words, “and he was added to the eleven apostles.” (v. 26)

The election of Matthias to serve as replacement for Judas gives us a paradigm for our own decision making. The first step, obviously, is the recognition that we are at a decision point: Judas is gone, something must be done. The second is recourse to Scripture. The early followers of Jesus had only the Hebrew Scriptures to which to turn; we have, in addition, the New Testament in which we are taught that there are two great commandments ~ Love God: Love your neighbor.

Every decision we make must honor these; there may be lesser rules within Holy Writ which provide guidance, but in the end, in making our decisions, we must follow these commandments above all else.

Once we have considered the guidance of Scripture, we must pray. My grandfather, the Methodist Sunday school teacher, taught me that the purpose of prayer is not to get what we want, but to make us into instruments for God to do what God wants: he was fond of saying that the Lord taught us to pray, “Thy will be done,” not “Thy will be changed.” The followers of Jesus in that upper room, faced with the monumental task of appointing a new apostle, prayed. So should we. This has been the church’s tradition from the very beginning.

Now, let’s be honest ~ the answer to prayer is often vague and often confusing. I know very few people who have ever received specific directions for their lives and, to be truthful, I view those who claim to have done so with great suspicion. Most of us will never know for certain which is the right choice; I suspect that even those in the upper room that day wondered, when all was said and done, whether Matthias was a better choice than Justus. But they chose, and we choose.

We do not do so blindly, however. As the confirmation response says, we choose “with God’s grace.” We read Scripture; we pray in accordance with church tradition; and we seek the guidance of others, reasoning together, testing our thoughts and our beliefs about prayer’s answers against those of trusted companions. Then we decide. Perhaps the choice to be made is clear; perhaps it is not so clear, but at least one choice seems better or wiser than others; or perhaps, like that first congregation, we come to a point where there are two or more choices that seem equally good and the best we can do is flip a coin and trust God. However we make the decision, we say, “I do … with the grace of God” and trust that that grace will sustain us in the decisions we make.

Sometimes, perhaps most times, our decisions will be wrong; they will be sinful. But Martin Luther once advised his friend Philipp Melanchthon, “Be a sinner, and let your sins be strong (sin boldly), but let your trust in Christ be stronger, and rejoice in Christ who is the victor over sin, death, and the world.” (Letter 99, Paragraph 13) Having studied Scripture, having prayed, having sought the counsel of others, we make our decisions boldly, trusting in the grace of God.

In our individual choices, we may not (indeed, we will not) reach the same decisions, but valuing this process of decision-making we are able to respect our differences of opinion, belief, practice, and action. In our corporate decision-making, by this process, we are able to reach consensus all can accept, as the disciples did in numbering Matthias one of the Twelve. In the end, “we know that all things work together for good for those who love God” (Rom 8:28), even our wrong choices and bad decisions.

Every ten years or so the bishops of the Anglican Communion, including the bishops of the Episcopal Church, gather with the Archbishop of Canterbury in what is called “The Lambeth Conference.” In 1930, Archbishop William Temple preached at the opening of the seventh Lambeth Conference, assuring his colleagues:

While we deliberate, God reigns;

When we decide wisely, God reigns;

When we decide foolishly, God reigns;

When we serve God in humble loyalty, God reigns;

When we serve God self-assertively, God reigns;

When we rebel and seek to withhold our service, God reigns —

the Alpha and the Omega, which is, and which was, and which is to come, the Almighty.

We decide however we decide . . . but Almighty God will always reign!

I do not know why each of those seventeen people last week knelt before the bishop and affirmed their commitment to Christ in the context of the Anglican tradition and in the community of the Episcopal Church. I know why I did (lo, those many years ago): because I found in the Episcopal Church not a uniformity of belief and practice, not a church which claims to know (and thus to dictate) how all of life’s choices and decisions are to be made, but rather a unity of mission, a community of harmony, a church which offers “appropriate welcome and gracious hospitality,” where Christians are encouraged to explore and make life’s decisions in the same way the embryonic Christian community elected Matthias: through reliance on Scripture, prayerful tradition, and reasoned reflection. Perhaps that is also why our newest confirmed members have chosen to join us.

Or, rather, why Jesus chose them, why the Father has given them to Jesus in the context of this community, why we welcome them and join with Christ praying for them and for ourselves as he prayed for his first followers: “May we be one, as he and the Father are one.” Amen.

====================

A request to my readers: I’m trying to build the readership of this blog and I’d very much appreciate your help in doing so. If you find something here that is of value, please share it with others. If you are on Facebook, “like” the posts on your page so others can see them. If you are following me on Twitter, please “retweet” the notices of these meditations. If you have a blog of your own, please include mine in your links (a favor I will gladly reciprocate). Many thanks!

====================

Father Funston is the rector of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Medina, Ohio.

Every year on Maundy Thursday in the Episcopal Church we do this thing: we gather for Eucharist and we hear these lessons – the story of the Passover from the Book of Exodus, St. Paul’s retelling of the institution narrative of the Eucharist, and St. John’s story of the Last Supper in which he focuses not on the meal but on Jesus’ act of humility and service during the meal (probably quite early in the evening) of washing the feet of the others present.

Every year on Maundy Thursday in the Episcopal Church we do this thing: we gather for Eucharist and we hear these lessons – the story of the Passover from the Book of Exodus, St. Paul’s retelling of the institution narrative of the Eucharist, and St. John’s story of the Last Supper in which he focuses not on the meal but on Jesus’ act of humility and service during the meal (probably quite early in the evening) of washing the feet of the others present. The four evangelists are traditionally represented by iconic depictions of the emphasis of their gospels. John, whose gospel is the longest and most different of the four tellings of Jesus’ story, is represented by an eagle because he emphasizes the divinity of Christ. Matthew, on the other hand, begins his gospel with Jesus’ genealogy and emphasizes the humanity of the Savior, so he is represented by a man. Luke emphasizes the sacrificial nature of Jesus’ ministry and mission; thus, he is represented by an ox or bull (often winged), the sort of animal offered in the Temple.

The four evangelists are traditionally represented by iconic depictions of the emphasis of their gospels. John, whose gospel is the longest and most different of the four tellings of Jesus’ story, is represented by an eagle because he emphasizes the divinity of Christ. Matthew, on the other hand, begins his gospel with Jesus’ genealogy and emphasizes the humanity of the Savior, so he is represented by a man. Luke emphasizes the sacrificial nature of Jesus’ ministry and mission; thus, he is represented by an ox or bull (often winged), the sort of animal offered in the Temple. Today is the Third Sunday in Lent but, being March 8, it is also the day set aside on the calendar (both that of the Church of England and that of the Episcopal Church) for us to remember a hero of the Anglican tradition, a World War I chaplain named Geoffrey Anketell Studdert-Kennedy. In 1914 he became the vicar of St. Paul’s, Worcester, UK, but a short while later, on the outbreak of war, Kennedy volunteered as a chaplain to the armed forces. He gained the nickname “Woodbine Willie,” for his practice of giving out Woodbine brand cigarettes to soldiers. In 1917, he won the United Kingdom’s Military Cross for bravery at Messines Ridge.

Today is the Third Sunday in Lent but, being March 8, it is also the day set aside on the calendar (both that of the Church of England and that of the Episcopal Church) for us to remember a hero of the Anglican tradition, a World War I chaplain named Geoffrey Anketell Studdert-Kennedy. In 1914 he became the vicar of St. Paul’s, Worcester, UK, but a short while later, on the outbreak of war, Kennedy volunteered as a chaplain to the armed forces. He gained the nickname “Woodbine Willie,” for his practice of giving out Woodbine brand cigarettes to soldiers. In 1917, he won the United Kingdom’s Military Cross for bravery at Messines Ridge. “Life is a banquet, and most poor suckers are starving to death!”

“Life is a banquet, and most poor suckers are starving to death!”

When Philip told Nathanael that he had found the Messiah and that he was the son of a carpenter from Nazareth, Nathanael’s immediate response was, “Can anything good come from Nazareth?” (Jn 1:46). Obviously Nazareth had a reputation, and not a good one. I often wonder if, as Jesus was making his way through the Holy Land, especially early in his ministry when he wasn’t well-known, people would ask him, “What was it like growing up in Nazareth?”

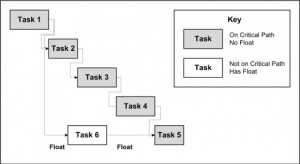

When Philip told Nathanael that he had found the Messiah and that he was the son of a carpenter from Nazareth, Nathanael’s immediate response was, “Can anything good come from Nazareth?” (Jn 1:46). Obviously Nazareth had a reputation, and not a good one. I often wonder if, as Jesus was making his way through the Holy Land, especially early in his ministry when he wasn’t well-known, people would ask him, “What was it like growing up in Nazareth?” Project Evaluation Review Technique – “PERT” . . . . I learned to do PERT charts in business school. PERT charts diagram the flow of a project through its various tasks and processes, assigning some as “essential” tasks which must be done in a particular order, later tasks depending on earlier tasks to have been accomplished by particular persons, while other tasks “float,” they can be done any time by any team member.

Project Evaluation Review Technique – “PERT” . . . . I learned to do PERT charts in business school. PERT charts diagram the flow of a project through its various tasks and processes, assigning some as “essential” tasks which must be done in a particular order, later tasks depending on earlier tasks to have been accomplished by particular persons, while other tasks “float,” they can be done any time by any team member. Truth, United States Senator Hiram Johnson observed in 1917, is the first casualty of war. When war becomes nearly universal is truth in danger of being fully obliterated? I don’t think so; I think truth will ultimately survive and prevail. My faith is that the Truth will no doubt prevail, but for the moment, I am speaking neither of grand philosophical concepts nor of the One who made the audacious claim, “I am the Truth.” (Jn 14:6) Rather, I speak simply of factual accuracy and of the intellectual integrity of those who communicate; that truth is suffering some mighty hurtful body blows at present.

Truth, United States Senator Hiram Johnson observed in 1917, is the first casualty of war. When war becomes nearly universal is truth in danger of being fully obliterated? I don’t think so; I think truth will ultimately survive and prevail. My faith is that the Truth will no doubt prevail, but for the moment, I am speaking neither of grand philosophical concepts nor of the One who made the audacious claim, “I am the Truth.” (Jn 14:6) Rather, I speak simply of factual accuracy and of the intellectual integrity of those who communicate; that truth is suffering some mighty hurtful body blows at present.