====================

A “Rector’s Reflection” offered by the Rev. Dr. C. Eric Funston in the December 2016 issue of The Epistle, the newsletter of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Medina, Ohio, where Fr. Funston is rector.

====================

A few years ago I read an essay about the trials and tribulations of relocation, particularly from region to region within our country. In it the author made the comment that when relocating to the South, there were two invariably asked questions of the newcomer: “Who are your people?” and “Where do you go to church?” These, he said, are quintessentially Southern inquiries which serve to position the interrogated in a place’s social network and milieu. The assumptions, of course, are that no one would relocate to a town where they did not have “people” (i.e., family members) and that everyone goes to church somewhere.

A few years ago I read an essay about the trials and tribulations of relocation, particularly from region to region within our country. In it the author made the comment that when relocating to the South, there were two invariably asked questions of the newcomer: “Who are your people?” and “Where do you go to church?” These, he said, are quintessentially Southern inquiries which serve to position the interrogated in a place’s social network and milieu. The assumptions, of course, are that no one would relocate to a town where they did not have “people” (i.e., family members) and that everyone goes to church somewhere.

I’m not sure, after making several regional locations myself, that those are only Southern questions. They seem to be universally asked, in one form or another, of newcomers to every American community. In fact, they may be quintessentially human questions asked around the world!

In 2005, when Evelyn and I made our first trip to Ireland, one of my goals was to find distant relatives, members of the Funston clan whose ancestors had stayed there when my great-great-grandfather had come to America. So we visited the places I believed he might have come from, the Funston township lands of Counties Donegal, Tyrone, and Fermanagh. During our stay in the city of Donegal we happened to visit a woolen goods store run by a delightful man named Sean McGinty. We entered the shop just as Sean was closing up for the day and he graciously stayed open so we could peruse his sweaters, tweeds, and other goods. Of course, that meant he was going to be late to dinner . . . and, as a result, his wife Mary came looking for him.

We’d been in conversation with Sean before Mary arrived and told him of my search for Funstons. He said he thought there might be some living in Pettigo, a small village on the border of County Donegal and County Fermanagh. When Mary came into the shop, he drew her into our conversation and asked her, “Mary, you’re from Pettigo. Were there any Funstons living there?” She thought for a moment and then replied, “Aye! But they weren’t our people.” I knew immediately what she meant: they weren’t members of the Catholic Church. And that would have been right! My ancestor was a member of the Anglican Church of Ireland and his descendants are still Anglicans!

So there were those same two concerns: “Who are your people?” and “Where do you go to church?” They are the questions still being asked of newcomers to our communities wherever we may be, whether we are in the South of the United States, in Ohio, or somewhere in Europe. As so many people are on the move because of war, political unrest, and economic necessity, as so many are labeled “immigrant” and “refugee,” they are increasingly divisive and exclusive questions.

“Who are your people?” . . . “Where do you worship?” . . . What is your ethnic background? . . . What is your religion? . . . Instead of being asked to position the newcomer within the social milieu of his or her new home, the questions and their answers too often lead to the erection of social barriers, sometimes even physical walls. Instead of being welcoming questions of inclusion, they are the defensive or belligerent interrogations of exclusion.

Recently in the Christian press, particularly those journals which cater to a more conservative audience, there has been a lot of discussion about the assertion that Jesus was an immigrant and refugee. It is a common enough hermeneutic drawn from the story of the Holy Innocents and the flight of the Holy Family into Egypt as related in Matthew’s Gospel: “An angel of the Lord appeared to Joseph in a dream and said, “Get up, take the child and his mother, and flee to Egypt, and remain there until I tell you; for Herod is about to search for the child, to destroy him.” (Matt 23:13 NRSV) It occurred to me that it may be a useful reminder that the Son of God was an immigrant from the very start, that he was not and is not a native resident of our world; he is from elsewhere, from heaven, from the very Throne of God.

As Dr. John Marshall, a Southern Baptist minister in Missouri, recently wrote: “Our Savior was an immigrant. He left His home in Heaven to become a stranger in the very world He created. There was no room for Him in the Bethlehem inn (Lk 2:7). He came to His own people, but they received Him not (Jn 1:11).” (Marshall) As we prepare once again to welcome him in the annual celebration of his Incarnation, we do well to remember that and to remember that he remained an immigrant and a refugee throughout his life.

Jesus was born in Bethlehem of Judea, a land dominated by the Roman empire through a client ruler named Herod the Great. Apparently Mary, Joseph, and Jesus remained there for a couple of years before fleeing to Egypt where they lived until Herod died about four to six years after that. When they left Egypt, they returned not to Bethlehem but to Nazareth in Galilee, which was under the rule of Herod’s son, Herod Antipas, Tetrarch of Galilee. Jesus grew up, then, as a resident of Galilee; when he undertook his ministry to Jerusalem (which is in Judea), although he was returning to the country of his birth, he was an immigrant into Judea.

Judea, by the way, during Jesus’ life and ministry was ruled not by a local king but directly by the Romans. Herod the Great was succeeded by his son Archelaus, who had the title of “Ethnarch of Judea.” Archelaus died less than ten years after succeeding his father. After his death, a series of Roman governors or “Prefects” ruled, the last of whom during Jesus’ life was Pontius Pilate.

In truth, Jesus spent most of his time on the move. Both Matthew and Luke report him saying to a potential follower, “Foxes have holes, and birds of the air have nests; but the Son of Man has nowhere to lay his head.” (Matt 8:20; Lk 9:58) Jesus was not a settled person and, interestingly enough, neither are his followers (us) supposed to be. This goes back to the Jewish roots of our faith, a reminder of which is found in the Torah’s instructions for eating the Passover feast: “You shall eat it [with] your loins girded, your sandals on your feet, and your staff in your hand; and you shall eat it hurriedly.” (Ex 12:11) We are always to be ready to be on the move.

Our parish patron, St. Paul, takes up this theme in his letters. He reminded the Philippians that we are not to set our mind on earthly things because “our citizenship is in heaven.” (Philip 3:19-20) And he promised the Ephesians that we are “citizens with the saints and also members of the household of God.” (Eph 2:19) Theologians Stanley Hauerwas and William Willimon expanded on this notion in their book Resident Aliens (Abingdon, 1989), arguing that today the church is not “a service club within a generally Christian culture,” but rather “a colony within an alien society.” (pg. 115)

How might this inform and shape our Advent preparations and our Christmas celebrations? What if we understood that we are not getting ready to welcome Jesus into our settled existence, our cozy homes and our warm hearths, our abundant feasts and our lovely dining rooms? Rather, we should be preparing for our immigrant Lord Jesus to invite us to join him on the road, to eat with him hastily consumed meals wearing our sandals and holding our walking sticks, to sleep with him in places where we have no place to put our heads. What might we do differently to get ready for the anniversary of his Incarnation and for his promised return? What might we do differently for all who, like him, are refugees and immigrants?

Who are our people? The people of God whoever they are and wherever they may be, temporarily settled in “a colony within an alien society” or on the road. Where do we worship? Wherever we find our Lord, in church, in a refugee camp, in places we cannot even imagine. Every year Advent and Christmas challenge us with what Hauerwas and Willimon call “the greatest challenge facing the church in any age” which is to be “a living, breathing, witnessing colony of truth.”

May that challenge be our blessing in 2016! May each of us, and all of us together, be living, breathing witnesses to the Truth!

(Note: The image is a digital painting by an internet blogger calling himself Horseman. I could find no further information about it or him.)

====================

A request to my readers: I’m trying to build the readership of this blog and I’d very much appreciate your help in doing so. If you find something here that is of value, please share it with others. If you are on Facebook, “like” the posts on your page so others can see them. If you are following me on Twitter, please “retweet” the notices of these meditations. If you have a blog of your own, please include mine in your links (a favor I will gladly reciprocate). Many thanks!

====================

Father Funston is the rector of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Medina, Ohio.

“Two will be in the field; one will be taken and one will be left. Two women will be grinding meal together; one will be taken and one will be left. Keep awake therefore, for you do not know on what day your Lord is coming.” (Matt 24:40-42) You probably have friends who have told you these verses from Matthew’s Gospel describe something called “the Rapture.” You may have read the Left Behind books or seen the movies. So you may think you have a handle on what these verses mean and why they are offered to us as we begin our Advent preparation to celebrate the anniversary of Christ’s Incarnation and to look forward to his return, his “Second Coming.”

“Two will be in the field; one will be taken and one will be left. Two women will be grinding meal together; one will be taken and one will be left. Keep awake therefore, for you do not know on what day your Lord is coming.” (Matt 24:40-42) You probably have friends who have told you these verses from Matthew’s Gospel describe something called “the Rapture.” You may have read the Left Behind books or seen the movies. So you may think you have a handle on what these verses mean and why they are offered to us as we begin our Advent preparation to celebrate the anniversary of Christ’s Incarnation and to look forward to his return, his “Second Coming.” On the day after the general election, a Presbyterian clergyman in Iowa, a married gay man, found a computer-printed note tucked under his car’s windshield wiper addressed to “Father Homo.” The text of the note began with the question “How does it feel to have Trump as your president?” and was both belittling and threatening. The same day a softball dugout in Island Park in Wellsville, New York, was defaced with graffiti reading “Make America White Again,” accompanied by a large swastika. The next day, students at nearby Canisius College, a Jesuit institution, found a black baby doll with a noose tied around its neck in the freshman dormitory elevator, and students at Wellesley College in Massachusetts witnessed two young white men drive a truck through their campus flying a Trump campaign banner, yelling “Make American Great Again,” and spitting on African-American young women.

On the day after the general election, a Presbyterian clergyman in Iowa, a married gay man, found a computer-printed note tucked under his car’s windshield wiper addressed to “Father Homo.” The text of the note began with the question “How does it feel to have Trump as your president?” and was both belittling and threatening. The same day a softball dugout in Island Park in Wellsville, New York, was defaced with graffiti reading “Make America White Again,” accompanied by a large swastika. The next day, students at nearby Canisius College, a Jesuit institution, found a black baby doll with a noose tied around its neck in the freshman dormitory elevator, and students at Wellesley College in Massachusetts witnessed two young white men drive a truck through their campus flying a Trump campaign banner, yelling “Make American Great Again,” and spitting on African-American young women. I’d like you all to take your Prayer Books in hand and turn with me to page 855 which is way in the back of the book in the section called The Catechism or Outline of the Faith. At the top of the page are three questions about the mission of the church and the answers to those questions that we as Episcopalians teach. I’m going to read the questions; I’d like you to read the answers:

I’d like you all to take your Prayer Books in hand and turn with me to page 855 which is way in the back of the book in the section called The Catechism or Outline of the Faith. At the top of the page are three questions about the mission of the church and the answers to those questions that we as Episcopalians teach. I’m going to read the questions; I’d like you to read the answers: Our first lesson today is from a book with the wholly amazing title The Book of the All-Virtuous Wisdom of Joshua ben Sira, usually (and mercifully) shortened to Sirach. It is accepted as part of the Christian biblical canon by Roman Catholics, the Eastern Orthodox, and most of the Oriental Orthodox churches. In our Anglican tradition, it is not accepted as canonical, but we do read it “for example of life and instruction of manners;” however, it cannot be used to establish any doctrine. (Article VI of the Articles of Religion, 1801) The book is in the tradition known as “wisdom literature;” basically, it is a collection of ethical teachings closely resembling the canonical Book of Proverbs, and serving the same function.

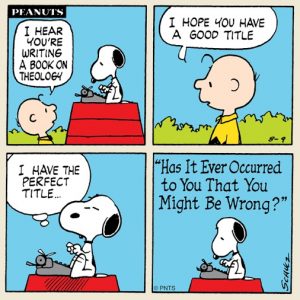

Our first lesson today is from a book with the wholly amazing title The Book of the All-Virtuous Wisdom of Joshua ben Sira, usually (and mercifully) shortened to Sirach. It is accepted as part of the Christian biblical canon by Roman Catholics, the Eastern Orthodox, and most of the Oriental Orthodox churches. In our Anglican tradition, it is not accepted as canonical, but we do read it “for example of life and instruction of manners;” however, it cannot be used to establish any doctrine. (Article VI of the Articles of Religion, 1801) The book is in the tradition known as “wisdom literature;” basically, it is a collection of ethical teachings closely resembling the canonical Book of Proverbs, and serving the same function. God’s response to Abraham’s challenge is to take Abraham outside and show him the stars and ask him, “Has it ever occurred to you that you might be wrong?” Well, God doesn’t, actually . . . but that’s what it boils down to. God’s response to Abraham is, “Thank again!”

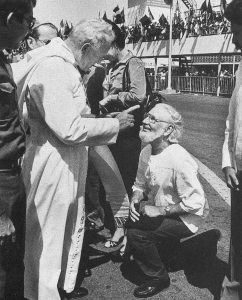

God’s response to Abraham’s challenge is to take Abraham outside and show him the stars and ask him, “Has it ever occurred to you that you might be wrong?” Well, God doesn’t, actually . . . but that’s what it boils down to. God’s response to Abraham is, “Thank again!” When Pope John Paul II scolded Fr. Cardenal upon the his arrival in Nicaragua, it was because Cardenal had collaborated with the Marxist Sandinistas and, after the Sandinista victory in 1979, he became their government’s Minister of Culture. His brother, Fr. Fernando Cardenal S.J. also worked with the Sandinista government in the Ministry of Education, directing a successful literacy campaign. There were a handful of other priests working in the government, as well.

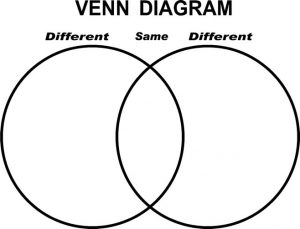

When Pope John Paul II scolded Fr. Cardenal upon the his arrival in Nicaragua, it was because Cardenal had collaborated with the Marxist Sandinistas and, after the Sandinista victory in 1979, he became their government’s Minister of Culture. His brother, Fr. Fernando Cardenal S.J. also worked with the Sandinista government in the Ministry of Education, directing a successful literacy campaign. There were a handful of other priests working in the government, as well.  We know that if there are tribal circles on that foundational paper, they are more like the circles on a Venn diagram, not only touching but overlapping. That was true of the ancient Hebrews; their tribalism might demand ethnic purity, but they never achieved it; the Old Testament demonstrates that, again and again! Modern ideological tribalism is no different. Ideologies, religious beliefs, political opinions differ in many ways, but in many others they share much in common; they overlap. People’s lives and opinions overlap, but ideological tribalism encourages us to hear only the differing opinions and blinds us to our similar lives.

We know that if there are tribal circles on that foundational paper, they are more like the circles on a Venn diagram, not only touching but overlapping. That was true of the ancient Hebrews; their tribalism might demand ethnic purity, but they never achieved it; the Old Testament demonstrates that, again and again! Modern ideological tribalism is no different. Ideologies, religious beliefs, political opinions differ in many ways, but in many others they share much in common; they overlap. People’s lives and opinions overlap, but ideological tribalism encourages us to hear only the differing opinions and blinds us to our similar lives. Some translations of the Bible like to add to it. They insert explanatory headings and titles into the teachings of the authors of scripture or before the parables or important elements in Jesus’ life and teachings. The New International Version, for example, adds the title “The Parable of the Rich Fool” to our gospel text for today. It breaks up our reading from Ecclesiastes with three such headings: “Everything Is Meaningless,” “Wisdom Is Meaningless,” and “Toil Is Meaningless.” If you have a bible like that, take those titles and subheadings with a very large grain of salt because they are simply not accurate!

Some translations of the Bible like to add to it. They insert explanatory headings and titles into the teachings of the authors of scripture or before the parables or important elements in Jesus’ life and teachings. The New International Version, for example, adds the title “The Parable of the Rich Fool” to our gospel text for today. It breaks up our reading from Ecclesiastes with three such headings: “Everything Is Meaningless,” “Wisdom Is Meaningless,” and “Toil Is Meaningless.” If you have a bible like that, take those titles and subheadings with a very large grain of salt because they are simply not accurate! Sometime during the summer of 1969 (for the life of me, I can’t recall exactly when) and again in August of 1973, I was privileged to walk along the Promenade des Anglais on the Mediterranean waterfront of Nice. I was very young (or so I now consider myself to have been) and, on that second occasion, very much in love (or so I then considered myself) with a young French woman named Josienne. We quickly lost touch when that summer and my time as a student at the Sorbonne came to an end, but I have always fondly remembered her. Nice was her home town and, I suspect, is probably her home now. And I wonder, now, where she was on the evening of Bastille Day 2016. I pray she was not on the Promenade.

Sometime during the summer of 1969 (for the life of me, I can’t recall exactly when) and again in August of 1973, I was privileged to walk along the Promenade des Anglais on the Mediterranean waterfront of Nice. I was very young (or so I now consider myself to have been) and, on that second occasion, very much in love (or so I then considered myself) with a young French woman named Josienne. We quickly lost touch when that summer and my time as a student at the Sorbonne came to an end, but I have always fondly remembered her. Nice was her home town and, I suspect, is probably her home now. And I wonder, now, where she was on the evening of Bastille Day 2016. I pray she was not on the Promenade. The week of the summer solstice was an interesting one in the Funston household.

The week of the summer solstice was an interesting one in the Funston household.  Why are we here? Well, for a wedding, of course. But, more specifically, you may be wondering why an old Episcopal priest from Ohio is here in an 18th Century Puritan meeting house trying to do 21st Century Anglo-Catholic ritual. The short answer is that Chris asked me to. Chris was my music director at St Paul’s Church in Medina, Ohio, when he was a student at Oberlin (which his mother reminded me yesterday was just a few weeks ago), and we’ve been friends ever since.

Why are we here? Well, for a wedding, of course. But, more specifically, you may be wondering why an old Episcopal priest from Ohio is here in an 18th Century Puritan meeting house trying to do 21st Century Anglo-Catholic ritual. The short answer is that Chris asked me to. Chris was my music director at St Paul’s Church in Medina, Ohio, when he was a student at Oberlin (which his mother reminded me yesterday was just a few weeks ago), and we’ve been friends ever since.