====================

This sermon was preached on the Fifth Sunday of Easter, May 18, 2014, at St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Medina, Ohio, where Fr. Funston is rector.

(The lessons for the day were: Acts 7:55-60; Psalm 31:1-5,15-16; 1 Peter 2:2-10; and John 14:1-14 . These lessons can be read at The Lectionary Page.)

====================

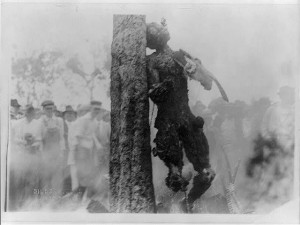

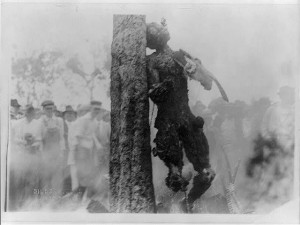

Does the name “Jesse Washington” mean anything to you? It’s unlikely that it does. If I tell you that Jesse Washington died in 1916 in Waco, Texas, would that spark any memory? Have you ever been taught about the incident in which Washington was killed? Have you ever heard of what came to be called “The Waco Horror?”

Does the name “Jesse Washington” mean anything to you? It’s unlikely that it does. If I tell you that Jesse Washington died in 1916 in Waco, Texas, would that spark any memory? Have you ever been taught about the incident in which Washington was killed? Have you ever heard of what came to be called “The Waco Horror?”

Probably not. It’s not one of the incidents of American history that gets regularly taught in our schools. If I hadn’t taken a course in African American history when I was a college sophomore in 1970, I wouldn’t know anything about the death of Jesse Washington on May 15, 1916. It’s not the sort of story that makes a white person comfortable. But I do know about it, and the fact that its anniversary falls during the week when I was preparing a sermon on, among other passages from Scripture, Luke’s description of the martyrdom of Stephen in the Book of Acts struck me as significant. Both Stephen and Jesse Washington were murdered by mobs because they were different.

Jesse Washington was a 17-year-old African American farmhand. On May 8, 1916, he was accused of raping and murdering Lucy Fryer, the wife of his white employer in Robinson, Texas, not far from Waco. Jesse and his entire family (his parents and a brother) were questioned; the others were released, but Jesse was not. He was taken to Dallas, where he eventually signed a confession which some legal historians believed was coerced. There was little, if any, evidence that he was actually guilty.

Washington was tried for murder in Waco, in a courtroom filled with locals who had been provoked by local newspaper reports which included lurid, and demonstrably false, details about the crime. His defense counsel entered a guilty plea and Washington was quickly sentenced to death, but he had no opportunity to appeal.

After his sentence was pronounced, the teenager was dragged out of the courtroom and lynched in front of city hall. Over 10,000 spectators, including city officials and police, gathered to watch. Members of the mob castrated the boy, cut off his fingers, and hung him (still alive) over a bonfire. He was repeatedly lowered into the fire and raised again to prolong his agony and death. After he finally succumbed, the fire was extinguished and Jesse Washington’s charred torso was dragged through the town; parts of his body were actually sold as souvenirs. A professional photographer took pictures as the lynching progressed; these were printed and sold as postcards in Waco.

As a Christian society, we remember Stephen as the first Christian martyr and as a hero of our faith; his is a unique story told in the Book of Acts. As a Christian society, we don’t remember Jesse Washington, at all; he’s just one of thousands who were lynched. Historical reports indicate that between 1882 and 1968 there were over 4,700 lynchings in the United States. One history text estimates that between 1882 and 1930 in America at least one black person was lynched every week. (Tolnay, S., & E.M. Beck, A Festival of Violence, University of Illinois Press, 1992, p. ix) We know the numbers, but we don’t know their names.

We Americans, however, aren’t even in the minor leagues when it comes to martyring people for being different. Writing about Stephen’s death, Professor Daniel Clendenin reminds us that there have been so many more martyrs, that martyrdom is not ancient history. It is a very contemporary and present reality:

Millions more have been martyred for reasons other than religion — for their ethnicity (Jews, Armenians, Tutsis), for economic ideology (farmers, land holders), social prejudice (intellectuals, artists), race (American blacks), and gender (women around the world like the inspirational Malala Yousafzai of Pakistan).

Christians are just one group among many that honors their martyrs. Very few times, places or peoples have been spared mass murder.

If you can bear to read it, I recommend the book by Daniel Jonah Goldhagen, Worse Than War; Genocide, Eliminationism, and the Ongoing Assault on Humanity (2009). Goldhagen estimates that between 127–175 million people were “eliminated” in the last century.

These people came from all regions of the world, and from all social, economic and political groups. The vast majority of these victims were killed in their own countries, by their fellow citizens, by willing and non-coerced murderers, and almost never with any substantial dissent. Eliminationism is thus “worse than war.”

The numbers are mind-numbing, and therein lies our challenge. They bring to mind the infamous remark by [Joseph] Stalin in 1947 about the famine in Ukraine that was killing millions: “If only one man dies of hunger, that is a tragedy. If millions die, that’s only statistics.” (The Stoning of Stephen)

Clendenin concludes, “The martyrdom of Stephen disabuses us of a sentimental gospel. It roots us in the real world of industrial scale slaughter. The one man Stephen helps us to remember the individual humanity of the millions of people we might otherwise forget.”

Now I want to draw our attention away from mass murder and martyrdom, and focus instead, for a moment, on one another. I’d like you for just a few seconds to look around the room, and just take note of who and what you see here. (A short, silent pause)

What did you see? A bunch of living stones? The members of a holy priesthood? A chosen race? A royal priesthood? A people chosen and named by God? This is what Peter says we should see, the building material for a spiritual house, eternal in the heavens, not made with hands, that mansion in which there are many rooms where Jesus assures his disciples there is a place for all of us. But is that how we see one another?

Philip asked Jesus to show them the Father and Jesus replied, “Have I been with you all this time, Philip, and you still do not know me? Whoever has seen me has seen the Father. How can you say, ‘Show us the Father’?” I sometimes wonder if Jesus’ answer would perhaps have been different if Philip had asked, “Show us God.”

In the creation story in the first chapter of Genesis we are told, “God created humankind in his image, in the image of God he created them; male and female he created them.” (Gen 1:27) If Philip had asked Jesus, “Show us God,” might Jesus not have said, “Look around you, Philip.” Archbishop Desmond Tutu is fond of reminding people of those words from Genesis and suggesting that we should genuflect to one another! In a paper entitled Religious Human Rights and the Bible, he wrote:

The life of every human person is inviolable as a gift from God. And since this person is created in the image of God and is a God carrier a second consequence would be that we should not just respect such a person but that we should have a deep reverence for that person. The New Testament claims that the Christian person becomes a sanctuary, a temple of the Holy Spirit, someone who is indwelt by the most holy and blessed Trinity. We would want to assert this of all human beings. We should not just greet one another. We should strictly genuflect before such an august and precious creature. The Buddhist is correct in bowing profoundly before another human as the God in me acknowledges and greets the God in you. This preciousness, this infinite worth is intrinsic to who we all are and is inalienable as a gift from God to be acknowledged as an inalienable right of all human persons. (Emory International Law Review, Vol. 10 (1996): 63-68)

Which brings me back to Stephen and Jesse Washington, and to a strange little short story by the author Shirley Hardie Jackson entitled The Lottery that was first published in The New Yorker in June, 1948.

Set in a small, contemporary American town, a small village of about 300 residents, the story concerns an annual ritual known as “the lottery” which is practiced to ensure a good harvest; one character quotes an old proverb, “Lottery in June, corn be heavy soon.” As the story opens, the locals are excited but a bit anxious on the eve of the lottery. Children are gathering stones as Mr. Summers and Mr. Graves make the paper slips for the drawing and draw up a list of all the families in town.

When they finish the slips and the list, the men put them into a black box, which is locked up in the safe at a local coal company. The next morning the townspeople gather at 10 a.m. in order to have everything done in time for lunch. First, the eldest male of each family in town draws a slip; there’s one for every household. Bill Hutchinson gets the one slip with a black spot, meaning that his family has been chosen. In the next round, each member of the Hutchinson family draws a slip, and Bill’s wife Tessie gets the black spot. Each villager then picks up a stone and they surround Tessie, and the story ends as Mrs. Hutchinson is stoned to death while the paper slips are allowed to fly off in the wind.

Shortly after it was published, Ms. Jackson said of her story that she had hoped that by setting the particularly brutal ancient rite of stoning (the same thing that was done to Stephen) in the present she would shock her readers with “a graphic dramatization of the pointless violence and general inhumanity in [our] own lives.” (San Francisco Chronicle, July 22, 1948.) Her story suggests that we human beings are more capable of honoring our rituals and our preconceptions than we are of honoring one another.

I think the true stories of Stephen of Jerusalem, of Jesse Washington of Waco, Texas, and of those millions of martyrs who have been “eliminated” amply demonstrate that she was right. Not only are we more capable of honoring our rituals and prejudices that we of honoring one another, we are demonstrably willing to murder one another to protect them.

We are because when we look around at our fellow human beings we do not see one another as divine; we do not see living stones; we do not see members of a royal priesthood. Blinded, or perhaps just numbed, by familiar ritual, by preconception, by the simple human need to conform, we do not appreciate one another as fellow citizens of a holy nation, “chosen and precious in God’s sight,” as bearing the image of God.

“Have I been with you all this time, Philip, and you still do not know me?” Jesus asked. I’m not the least bit surprised in Philip, however; we human beings, made in the image of God, have been with each other for a long, long time, and we still do not know each other. Dr. Clendenin suggested that the martyrdom of Stephen helps us to remember the individual humanity of the millions of unnamed martyrs we might otherwise forget; may it also help us to remember the divinity of each of them and of each other.

Let us pray:

O God, you made us in your own image and redeemed us through Jesus your Son: Look with compassion on the whole human family; take away the arrogance and hatred which infect our hearts; break down the walls that separate us; unite us in bonds of love; and work through our struggle and confusion to accomplish your purposes on earth; that, in your good time, all nations and races may serve you in harmony around your heavenly throne; through Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen. (For the Human Family, Book of Common Prayer, Episcopal Church, 1979, page 815)

====================

A request to my readers: I’m trying to build the readership of this blog and I’d very much appreciate your help in doing so. If you find something here that is of value, please share it with others. If you are on Facebook, “like” the posts on your page so others can see them. If you are following me on Twitter, please “retweet” the notices of these meditations. If you have a blog of your own, please include mine in your links (a favor I will gladly reciprocate). Many thanks!

====================

Father Funston is the rector of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Medina, Ohio.

The scapegoat! One of the little-known but very often mentioned figures of the Old Testament is the scapegoat. If I were a betting man, I would bet that very few people actually know the origin of this term that nearly everyone has used at some time or another. Well, here it is in Israel’s ancient ritual of atonement.

The scapegoat! One of the little-known but very often mentioned figures of the Old Testament is the scapegoat. If I were a betting man, I would bet that very few people actually know the origin of this term that nearly everyone has used at some time or another. Well, here it is in Israel’s ancient ritual of atonement. What is joy? A bible study group at church grappled with that question recently and I’m still thinking about the question, so these concluding verses of today’s evening psalm got my attention. It’s not just a matter of defining emotion. Joy is a religious attitude, a stance toward God mentioned numerous of times in the Holy Scriptures; according to St. Paul, it is one of the “fruits of the Spirit.” (Gal 5:22) It’s important to know what we mean when we name it.

What is joy? A bible study group at church grappled with that question recently and I’m still thinking about the question, so these concluding verses of today’s evening psalm got my attention. It’s not just a matter of defining emotion. Joy is a religious attitude, a stance toward God mentioned numerous of times in the Holy Scriptures; according to St. Paul, it is one of the “fruits of the Spirit.” (Gal 5:22) It’s important to know what we mean when we name it. Does the name “Jesse Washington” mean anything to you? It’s unlikely that it does. If I tell you that Jesse Washington died in 1916 in Waco, Texas, would that spark any memory? Have you ever been taught about the incident in which Washington was killed? Have you ever heard of what came to be called “The Waco Horror?”

Does the name “Jesse Washington” mean anything to you? It’s unlikely that it does. If I tell you that Jesse Washington died in 1916 in Waco, Texas, would that spark any memory? Have you ever been taught about the incident in which Washington was killed? Have you ever heard of what came to be called “The Waco Horror?” Let me make one thing clear: I do not want to get into the abortion debate! I never want to get into the abortion debate!

Let me make one thing clear: I do not want to get into the abortion debate! I never want to get into the abortion debate! It has been almost 40 years since presidential candidate Jimmy Carter admitted to Playboy magazine, “I’ve looked on many women with lust. I’ve committed adultery in my heart many times. God knows I will do this and forgives me.” Caused quite a stir and, some say, marked the beginning of the erosion of presidential privacy, the start of an era of leadership toxicity in American politics when partisan reporters feel free to reveal any fact or rumor, no matter how irrelevant, if it will hurt a politician of the opposite party or position. I’m not sure that that’s the case; a good argument can be made that the current polarized, hyper-partisan atmosphere started building during the Nixon, or even Johnson, years. That, however, is not what I’m thinking about this morning.

It has been almost 40 years since presidential candidate Jimmy Carter admitted to Playboy magazine, “I’ve looked on many women with lust. I’ve committed adultery in my heart many times. God knows I will do this and forgives me.” Caused quite a stir and, some say, marked the beginning of the erosion of presidential privacy, the start of an era of leadership toxicity in American politics when partisan reporters feel free to reveal any fact or rumor, no matter how irrelevant, if it will hurt a politician of the opposite party or position. I’m not sure that that’s the case; a good argument can be made that the current polarized, hyper-partisan atmosphere started building during the Nixon, or even Johnson, years. That, however, is not what I’m thinking about this morning. I usually prefer the Prayer Book Psalter to the NRSV translation of the Psalms, but in today’s readings I find the latter rather more compelling. The NRSV makes it clear who the “they” is in this verse (which is repeated again at verse 14). “They” are “the nations,” which in the Hebrew bible always refers to ethnic groups other than the tribes of Israel. The BCP version refers to “the ungodly,” which is decidedly unclear; it could refer to individuals and, further, could refer even to persons from within the Jewish people, neither of which understandings would be accurate.

I usually prefer the Prayer Book Psalter to the NRSV translation of the Psalms, but in today’s readings I find the latter rather more compelling. The NRSV makes it clear who the “they” is in this verse (which is repeated again at verse 14). “They” are “the nations,” which in the Hebrew bible always refers to ethnic groups other than the tribes of Israel. The BCP version refers to “the ungodly,” which is decidedly unclear; it could refer to individuals and, further, could refer even to persons from within the Jewish people, neither of which understandings would be accurate.  The translators of the NRSV are a bunch of prudes; a better translation of the last verse of this section would be “. . . you shall see my butt.”

The translators of the NRSV are a bunch of prudes; a better translation of the last verse of this section would be “. . . you shall see my butt.” “I threw it into the fire, and out came this calf!”

“I threw it into the fire, and out came this calf!” “Wrestling in his prayers” seems such an odd turn of phrase! Aren’t prayers supposed to be peaceful? The image of prayer as athletic competition (and vigorous, muscular, and very personal competition, at that) just seems contradictory. But the contradiction calls to mind two thoughts.

“Wrestling in his prayers” seems such an odd turn of phrase! Aren’t prayers supposed to be peaceful? The image of prayer as athletic competition (and vigorous, muscular, and very personal competition, at that) just seems contradictory. But the contradiction calls to mind two thoughts. Sometime this fall, probably during October, my wife and I will become grandparents for the first time. Last night, a friend asked, “What will you be called?” Because the question came out of the blue (we hadn’t been discussing children or grandchildren), I didn’t know what he was asking — and my face must have shown it. “As grandfather,” he clarified, “what will you be called as a grandparent?”

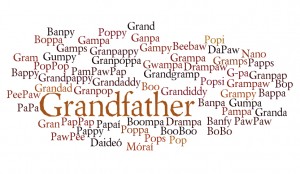

Sometime this fall, probably during October, my wife and I will become grandparents for the first time. Last night, a friend asked, “What will you be called?” Because the question came out of the blue (we hadn’t been discussing children or grandchildren), I didn’t know what he was asking — and my face must have shown it. “As grandfather,” he clarified, “what will you be called as a grandparent?”