====================

This sermon was preached on the Eighth Sunday after Pentecost, July 14, 2013, at St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Medina, Ohio, where Fr. Funston is rector.

(Revised Common Lectionary, Pentecost 8 (Proper 10, Year C): Amos 7:7-17; Psalm 82; Colossians 1:1-14; and Luke 10:25-37. These lessons can be read at The Lectionary Page.)

====================

The nation’s legal system is corrupt; justice is for sale to the highest bidder. The guilty go free while the innocent suffer and die. The rich are crushing the poor. The affluent, the 1%-ers, are living a lavish life, with their costly perfumes and cosmetics, and their vacation homes with expensive furnishings, pleasure palaces where they can throw extravagant parties with music in every room. They revel in sexual debauchery of all sorts, but try to enforce a puritanical moral code on the rest of society. The poor are at the mercy of predatory lenders who exploit vulnerable families. The rich have more than enough to eat and to waste, while the poorest in the society go hungry. And government and religious leaders not only allow this to happen, they help it happen.

The nation’s legal system is corrupt; justice is for sale to the highest bidder. The guilty go free while the innocent suffer and die. The rich are crushing the poor. The affluent, the 1%-ers, are living a lavish life, with their costly perfumes and cosmetics, and their vacation homes with expensive furnishings, pleasure palaces where they can throw extravagant parties with music in every room. They revel in sexual debauchery of all sorts, but try to enforce a puritanical moral code on the rest of society. The poor are at the mercy of predatory lenders who exploit vulnerable families. The rich have more than enough to eat and to waste, while the poorest in the society go hungry. And government and religious leaders not only allow this to happen, they help it happen.

Just a brief summary of Chapters 1 through 6 of the Prophet Amos.

Some of you probably thought, “There he goes again, spouting his liberal politics from the pulpit.” But I’m not; as I said, it’s simply a paraphrase the Prophet Amos’s critique, of God’s critique, of ancient Israel at the time of King Jeroboam II. We just heard most of chapter 7 beginning at verse 7, in which Amos tells of the third of three prophetic visions. In verses 1 through 6, Amos tells of God showing him locusts devouring all the crops of the land and then another vision of fire destroying everything in the nation. Amos pleads with God not to let that happen. Most scholars interpret those visions as omens of what God might do to the nation, but I think perhaps they might instead be striking visions of prophetic judgment against the wealthy of ancient Israel and the rulers and religious leaders of the time. These are not visions of what God might do; they are visions of what those in power will do if not stopped. And God’s judgment spoken twice to Amos is, “This will not happen!” (vv. 3, 6)

So God shows Amos a vision of a plumb line. Do you know what a plumb line is? There’s a picture of a plumb line on the cover of the bulletin this morning. A plumb line is a string with a metal weight, or “plumb bob,” at one end which, when suspended, points directly towards the earth’s center of gravity so that the string hangs perpendicular to the plane of the earth’s surface; it is used to test the verticality of structures, how true to straight up-and-down they are. It sets the standard for up-rightness. God tells Amos that God is setting a metaphorical plumb line in the midst of God’s People and if they don’t measure up to the standard, “the high places of Isaac shall be made desolate, and the sanctuaries of Israel shall be laid waste, and [God] will rise against the house of Jeroboam with the sword.”

Well, you say, that’s ancient Israel. What’s that got to do with us?

Let me read you a news item from the past week. This is from the July 9, 2013, issue of the Florence, Alabama, Times-Daily:

Police Chief Lyndon McWhorter said Monday morning’s bank robbery [in Moulton, Alabama] was among the most unusual of his law enforcement career.

“I’ve been involved with several over the years, but none like this,” McWhorter said. “It’s one for the books.”

McWhorter said Rickie Lawrence Gardner, 49, of 7667 Alabama 33, Moulton, was arrested Monday morning while sitting on a bench outside the Bank Independent branch on Court Street in Moulton, minutes after he supposedly walked in and robbed the bank.

“When the officers got there, he was just sitting on the bench, waiting on them,” McWhorter said. “The money was locked up inside his truck, which was parked in the handicapped spot in front of the bank.

“He had a handicap sticker on his vehicle so he even parked legal.”

McWhorter said Gardner told authorities he robbed the bank because he had hurt his leg and wasn’t able to take care of himself.

“So, he decided to get arrested to have a place to live and someone to take care of him.”

Minutes before the arrest, McWhorter said, Gardner walked into the bank just off Alabama 157 and handed a teller a written note explaining that he had a gun and she was to give him money.

Authorities said no weapon, other than a pocketknife, was found when Gardner was taken into custody.

“The only thing he said to the teller was when he asked her to give him a bag to put the money in,” McWhorter said.

With the money in hand, McWhorter said Gardner walked out of the bank, laid the money inside his vehicle, locked the door and walked back to the bench. The chief said Gardner sat down on the wooden bench in front of the bank and waited on officers.

“When officers got there, he did not offer any kind of resistance. He was just waiting on them,” McWhorter said. “This is the first bank robbery I’ve ever worked where the robber was waiting outside the bank for the police to turn himself in.” (Times-Daily)

The Associated Press later reported that Gardner “mentioned the weapon in the note — even though he didn’t have one — because he thought it would get him a longer sentence;” he thought he’d get more time, which would mean more shelter, more food. (AP Story)

The reason you may have thought my opening paraphrase of Amos sounded like an indictment of our own society is simple. It does. The word of prophecy spoken by Amos to ancient Israel speaks directly to us.

You know the interesting thing about Amos’s prophecy is that we can’t even be sure it was heard by the rulers of the nation to which it was spoken. We know Amos wrote it down; we know that someone told the story of Amos delivering his prophecy to Amaziah (who was the high priest at Bethel the religious center of the northern kingdom), but we are told that Amaziah never delivered it to Jeroboam II, the reigning king.

Amaziah instead told the king that Amos was part of a conspiracy to kill him, and then Amaziah told Amos to return to his home which was in the southern kingdom. “O seer, go, flee away to the land of Judah,” he says, “earn your bread there, and prophesy there; but never again prophesy at Bethel, for it is the king’s sanctuary, and it is a temple of the kingdom.” And this is where Amos speaks one of my favorite lines in Scripture, “I am no prophet, nor a prophet’s son; but I am a herdsman, and a dresser of sycamore trees.”

Amos’s answer was to indicate that he was not a prophet by profession; he was not a member of one of the official “prophecy schools.” Indeed, as part of the official religious establishment, Amos thought those full-time prophets were as much a part of the problem as the priests, the king, and the wealthy! Amaziah proved that he was part of the problem by failing to communicate Amos’s prophecy to King Jeroboam, so our reading today ends with Amos’s personal prophecy against him: “Your wife shall become a . . . and your sons and your daughters shall fall by the sword . . . and you shall die in an unclean land.” A pretty pointed prophecy, if ever there was one!

But we, who hear in Amos’s condemnation of ancient Israel at least a bit of a word of warning to our own society, what are we to make of this prophecy of the plumb line? The standard for the People of God in Israel was the ancient law of Moses, the religious, ethical, and social rules we find in Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, and Numbers (Deuteronomy was unknown at the time of Amos). What is it for us? How are we (as Paul wrote to the Colossians) to be “be filled with the knowledge of God’s will in all spiritual wisdom and understanding?” How are we to “lead lives worthy of the Lord, fully pleasing to him?” How are we to bear fruit in every good work and . . . grow in the knowledge of God?”

Well, that standard is easily stated. A young lawyer does so in today’s Gospel: “You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your strength, and with all your mind; and your neighbor as yourself.” It’s easily stated; it’s not so easily understood.

The young lawyer says as much when he asks his follow up question, “Who is my neighbor?” He wants to know what we want to know: are there limits? Is it sufficient to love only the people of my community — for him, Israel; for most of us, white descendants of Northern European immigrants? Does it include Mr. Gardner, the bank robber in Moulton, Alabama? Might it also include other undesirables, Samaritans and Gentiles, the Irish, descendants of African slaves, recently immigrated Asians, Hispanics? Does it include women, people with disabilities, lepers, and others frequently excluded from society? Do we get to define who is our neighbor, or does Someone else?

Ultimately, the answer to our question is the answer to another question: “Who does God love?” Jesus answers the question by telling a parable, the oh-so-familiar story of the “Good Samaritan.” In analyzing this story, Lutheran theologian Brian Stoffregen asks an important question: “Why does Jesus make the hero of this story a Samaritan?” In answering this question he writes:

The idea of being a “Good Samaritan” is so common in our culture, that most people today don’t realize that “Good Samaritan” would have been an oxymoron to a first century Jew. Briefly stated, a Samaritan is someone from Samaria. During an ancient Israeli war, most of the Jews living up north in Samaria were killed or taken into exile. However, a few Jews, who were so unimportant that nobody wanted them, were left in Samaria. Since that time, these Jews had intermarried with other races. They were considered half-breeds by the “true” Jews. They had perverted the race. They had also perverted the religion. They looked to Mt. Gerizim as the place to worship God, not Jerusalem. They interpreted the Torah differently than the southern Jews. The animosity between the Jews and Samaritans were so great that some Jews would go miles out of their way to avoid walking on Samaritan territory. Previously in Luke, the Samaritans had refused to welcome Jesus — the “bad” Samaritans. I’m certain that in the minds of many Jews, the only “good” Samaritan was a dead Samaritan. Note that the lawyer never says “Samaritan.” He can’t call him a “good Samaritan” (a phrase that doesn’t occur in the text). Anyway, we are still left with the question, “Why a Samaritan?”

If Jesus were just trying to communicate that we should do acts of mercy to the needy, he could have talked about the first man and the second man who passed by and the third one who stopped and cared for the half-dead man in the ditch. Knowing that they were a priest, Levite, and Samaritan is not necessary.

If Jesus were also making a gibe against clerics, we would expect the third man to be a layman — an ordinary Jew — in contrast to the professional clergy. It is likely that Jewish hearers would have anticipated the hero to be an ordinary Jew.

If Jesus were illustrating the need to love our enemies, then the man in the ditch would have been a Samaritan who is cared for by a loving Israelite.

One answer to the question: “Why a Samaritan?” is that we Christians might be able to learn about showing mercy from people who don’t profess Christ. I know that I saw much more love expressed towards each by the clients at an inpatient alcoholic/drug rehab hospital than I usually find in churches. Can we learn about “acting Christianly” from AA or the Hell’s Angels? (CrossMarks)

But Stoffregen proposes an alternative response: “Another answer to the question: ‘Why a Samaritan?’ is that we are not to identify with the Samaritan. A Jew would find that so distasteful that he couldn’t identify with that person. He wouldn’t want to be like the Priest or Levite in the story, so that leaves the hearer with identifying with the man in the ditch.” And that raises the further question, “Then who is the Samaritan?” to which there can only be one answer, “The Samaritan is God.”

If the Samaritan represents God, that means that God loves the penniless, the stripped naked, the beaten down, the ones left half dead, the ones passed-by by the leaders of society, by the rulers, by the punctiliously correct, and (I’m sorry to say) by the religious. It makes us realize that God is no respecter of position or wealth, God does not care about social class or religion. The man in the ditch had been stripped of everything that might have indicated his social standing, his religious faith, even his nationality; he was simply a person in need. That is who God loves, and that means that God loves everyone. In the human community, every person is potentially a person in need; truth be told, every person is a person in need.

Who is my neighbor? Who does God love? Everyone. No exceptions. No exclusions. That is the standard, the rule, the plumb line by which God judges society. This again and again is what the prophets of old told us; it is what Jesus told us; it is what our own modern prophets have said over and over. For example:

In the 18th Century, Dr. Samuel Johnson’s biographer James Boswell quoted him as saying, “A decent provision for the poor is the true test of civilization.” (Boswell, Life of Johnson)

In her book My Several Worlds (1954), Pearl S. Buck, wrote: “The test of a civilization is the way that it cares for its helpless members.”

In his last political speech, Sen. Hubert Humphrey said, “The moral test of government is how that government treats those who are in the dawn of life, the children; those who are in the twilight of life, the elderly; those who are in the shadows of life; the sick, the needy and the handicapped.”

And Mahatma Gandhi said, “A nation’s greatness is measured by how it treats its weakest members.”

Who is my neighbor? Who does God love? Everyone. No exceptions. No exclusions.

Every person is potentially a person in need, and every person is potentially a caregiver, a supplier of that which is needed. When we conclude our worship this morning, several young people and a few adults accompanying them will depart for Franklin, Pennsylvania, to be suppliers of that which is needed. At this point, they don’t know whose needs they are going to be supplying; they don’t know what those needs will be. All they know is that there are people in need and they are going to care for them, because they are our neighbors.

So at this point, let’s get on with the business of commissioning them for the ministry on which they are about the embark.

====================

A request to my readers: I’m trying to build the readership of this blog and I’d very much appreciate your help in doing so. If you find something here that is of value, please share it with others. If you are on Facebook, “like” the posts on your page so others can see them. If you are following me on Twitter, please “retweet” the notices of these meditations. If you have a blog of your own, please include mine in your links (a favor I will gladly reciprocate). Many thanks!

====================

Father Funston is the rector of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Medina, Ohio.

Jesus had healed someone on the sabbath; that’s the simple back ground to the Pharisees and Herodians conspiracy against Jesus. This alliance is an interesting one since in generally the two groups hated one another! But their fear of Jesus apparently was enough to get them to work together against him.

Jesus had healed someone on the sabbath; that’s the simple back ground to the Pharisees and Herodians conspiracy against Jesus. This alliance is an interesting one since in generally the two groups hated one another! But their fear of Jesus apparently was enough to get them to work together against him. Occasionally when studying Scripture I have thought, “This can’t possibly have happened.” I’m sure that what I am reading is meant to be an allegory or a metaphor, or that it is simply pious legend that the biblical author has incorporated into his story. This strange little story of the death of Herod Agrippa I was one of those passages. It’s just a little weird.

Occasionally when studying Scripture I have thought, “This can’t possibly have happened.” I’m sure that what I am reading is meant to be an allegory or a metaphor, or that it is simply pious legend that the biblical author has incorporated into his story. This strange little story of the death of Herod Agrippa I was one of those passages. It’s just a little weird.  Last week, The Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life published the results of

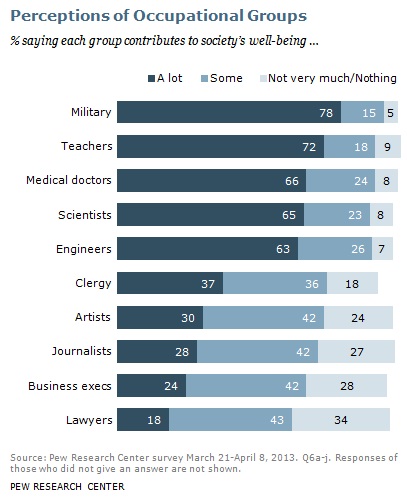

Last week, The Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life published the results of

The nation’s legal system is corrupt; justice is for sale to the highest bidder. The guilty go free while the innocent suffer and die. The rich are crushing the poor. The affluent, the 1%-ers, are living a lavish life, with their costly perfumes and cosmetics, and their vacation homes with expensive furnishings, pleasure palaces where they can throw extravagant parties with music in every room. They revel in sexual debauchery of all sorts, but try to enforce a puritanical moral code on the rest of society. The poor are at the mercy of predatory lenders who exploit vulnerable families. The rich have more than enough to eat and to waste, while the poorest in the society go hungry. And government and religious leaders not only allow this to happen, they help it happen.

The nation’s legal system is corrupt; justice is for sale to the highest bidder. The guilty go free while the innocent suffer and die. The rich are crushing the poor. The affluent, the 1%-ers, are living a lavish life, with their costly perfumes and cosmetics, and their vacation homes with expensive furnishings, pleasure palaces where they can throw extravagant parties with music in every room. They revel in sexual debauchery of all sorts, but try to enforce a puritanical moral code on the rest of society. The poor are at the mercy of predatory lenders who exploit vulnerable families. The rich have more than enough to eat and to waste, while the poorest in the society go hungry. And government and religious leaders not only allow this to happen, they help it happen.  What is a church building? It’s a holy place. It’s a place where people gather to worship. It’s a place where people encounter God. It’s a place where God’s people enjoy one another’s company. It’s a place where people get married, where babies are baptized, where funerals are held, where memories are made and lives remembered. It’s a place where the stories of faith are told and retold. It’s a place we teach and it’s a place where we learn.

What is a church building? It’s a holy place. It’s a place where people gather to worship. It’s a place where people encounter God. It’s a place where God’s people enjoy one another’s company. It’s a place where people get married, where babies are baptized, where funerals are held, where memories are made and lives remembered. It’s a place where the stories of faith are told and retold. It’s a place we teach and it’s a place where we learn. The Psalmist might think that this is what has happened in the mountains around my home town of Las Vegas, Nevada.

The Psalmist might think that this is what has happened in the mountains around my home town of Las Vegas, Nevada.  Do you know where Cyrene was? Its location was in the same place as present day Shahhat, a town in northeastern Libya, about 80 miles northeast of Benghazi and about five miles from the Mediterranean coast. It’s nearly 1300 miles from Jerusalem. Simon had “come from the country” a fair distance! And at the end of that very long journey, he was made to carry the cross up the hill to Golgotha. The journey is a common metaphor of the Christian life; Simon’s long journey could stand as an example. But does the metaphor, does Simon’s example make sense anymore?

Do you know where Cyrene was? Its location was in the same place as present day Shahhat, a town in northeastern Libya, about 80 miles northeast of Benghazi and about five miles from the Mediterranean coast. It’s nearly 1300 miles from Jerusalem. Simon had “come from the country” a fair distance! And at the end of that very long journey, he was made to carry the cross up the hill to Golgotha. The journey is a common metaphor of the Christian life; Simon’s long journey could stand as an example. But does the metaphor, does Simon’s example make sense anymore? Independence Day is one of the few secular holidays to have lessons of its own in both the Eucharistic and Daily Office Lectionaries of the Episcopal Church. There is a set of lessons in the regular Daily Office schedule of readings for today, as well, and I am intrigued that the way the calendar falls this year the Gospel for that set is the unjust trial of Jesus. One could meditate for hours on the meaning to be drawn from that juxtaposition.

Independence Day is one of the few secular holidays to have lessons of its own in both the Eucharistic and Daily Office Lectionaries of the Episcopal Church. There is a set of lessons in the regular Daily Office schedule of readings for today, as well, and I am intrigued that the way the calendar falls this year the Gospel for that set is the unjust trial of Jesus. One could meditate for hours on the meaning to be drawn from that juxtaposition. The Book of Acts, the earliest church history, tells us that the followers of Jesus practiced daily prayer: “Day by day, as they spent much time together in the temple, they broke bread at home and ate their food with glad and generous hearts.” (Acts 2:46) Eventually, the Christians were excluded from Jewish worship assemblies, either by their own choice or by action of the authorities, and in an unrelated development, the Temple was destroyed in 70 AD. Where, then, did Christians pray together? Or, for that matter, alone?

The Book of Acts, the earliest church history, tells us that the followers of Jesus practiced daily prayer: “Day by day, as they spent much time together in the temple, they broke bread at home and ate their food with glad and generous hearts.” (Acts 2:46) Eventually, the Christians were excluded from Jewish worship assemblies, either by their own choice or by action of the authorities, and in an unrelated development, the Temple was destroyed in 70 AD. Where, then, did Christians pray together? Or, for that matter, alone? In the assembly of the elders of the people, the chief priests and the scribes, Jesus is asked, “Are you the Messiah?” and in response he gives vent to some very real human frustration.

In the assembly of the elders of the people, the chief priests and the scribes, Jesus is asked, “Are you the Messiah?” and in response he gives vent to some very real human frustration.