====================

This sermon was preached on the Tenth Sunday after Pentecost, July 28, 2013, at St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Medina, Ohio, where Fr. Funston is rector.

(Revised Common Lectionary, Pentecost 10 (Proper 12, Year C): Hosea 1:2-10; Psalm 85; Colossians 2:6-19; and Luke 11:1-13. These lessons can be read at The Lectionary Page.)

====================

“Name this child.” That’s what I say to parents of infant baptismal candidates as I take their children from them. The words are not actually written in the baptismal service of The Book of Common Prayer as they are in some other traditions’ liturgies, but there is a rubric on page 307 that says, “Each candidate is presented by name to the Celebrant . . . .” so asking for the child’s name is a practical way of seeing that done. It’s practical, but it’s also a theological statement.

“Name this child.” That’s what I say to parents of infant baptismal candidates as I take their children from them. The words are not actually written in the baptismal service of The Book of Common Prayer as they are in some other traditions’ liturgies, but there is a rubric on page 307 that says, “Each candidate is presented by name to the Celebrant . . . .” so asking for the child’s name is a practical way of seeing that done. It’s practical, but it’s also a theological statement.

There is a common religious belief found in nearly all cultures that knowing the name of a thing or a person gives one power over that thing or person. One finds this belief among African and North American indigenous tribes, as well as in ancient Egyptian, Vedic, and Hindu traditions; it is also present in all three of the Abrahamic religions, Judaism, Christianity, and Islam.

The naming we do at baptism echoes the naming that takes place in Jesus’ tradition as a faithful Jew. In Judaism, when a male infant is circumcised on the eighth day after his birth, the mohel who performs the brit milah prays, “Our God and God of our fathers, preserve this child for his father and mother, and his name in Israel shall be called ________” and the prayer continues that, by his naming, the infant will be enrolled in the covenant of God with Israel. The same thing is done when a girl is named in the ceremony called zeved habat, or “presentation of the daughter” at the first formal reading of the Torah following her birth. In baptism, we do the same; the church says to its newest member, “This is who you are: washed in the waters of baptism, sealed by the Holy Spirit, and marked as Christ’s own forever,” a brother or sister in the church, a fellow member of the household of God.

To give a name to anything, especially to another human being, is a powerful thing! In the first verses of Genesis we are told, “God said ‘Let there be Light’ and there was light.” (Gen. 1:3) God named the light before it was created; this process continues through the rest of the story. God says, “Let there be” and names the thing which will come into existence; the naming seems a necessary first step in creation. There is a sense in which the name given shapes the future of the thing, or of the person, named.

So this morning I will ask that question of Danny and Nikki ___________ (parents) and of Peter ___________ (Godfather) who will name Ryan George __________ (infant) as a child of God, and of Mary __________ (sponsor) who will name Jacqueline Ann ____________ (adult) as a child of God, and through baptism we all will welcome Ryan and Jackie into the household of faith, into a covenant relationship with Almighty God and with each of us.

In today’s lesson from the Prophet Hosea, we find God instructing the prophet to give strange and bewildering names to his children as powerful, prophetic signs of Israel’s broken relationship with God. Hosea’s firstborn son is to be named Jezreel, which refers to the location of a particularly brutal and bloody massacre of Israelite royalty; his daughter is to be called, Lo-ruhamah, which means “no pity,” as a sign that God will have no compassion for his people who have gone astray; and a second son is to be named, Lo-ammi, which means “no people,” to let the Israelites know they are no longer God’s people.

Preachers often use their children as sermon illustrations, but what God demands of Hosea seems a little extreme. These poor kids aren’t going to have to live merely with the embarrassment of a single sermon, they are going to live with these names, these prophetic, judgmental names for their entire lives! But as bad as that is, giving these awful names to his children is not the hardest thing God demands of Hosea. No, the hardest thing is marrying their mother, Gomer.

Hosea is ordered by God to (in the words of our NRSV translation) “take for yourself a wife of whoredom and have children of whoredom.” He is to marry a prostitute who will continue in her scandalous and adulterous behavior, even though Hosea will be faithful to her throughout the marriage. Why? Because it is a prophetic sign, a prophetic action symbolizing the way in which Israel has dealt with God: because “the land commits great whoredom by forsaking the Lord.” God loves Israel with all the passion and loyalty of a faithful husband, but Israel, like a promiscuous wife, has been unfaithful to God.

It is an unfortunate prophetic metaphor, for it is misogynistic to the core! Portraying God as a faithful (but dominant) husband and Israel as a supposed-to-be obedient (and submissive) wife perpetuates a patriarchalism that is inappropriate to our society. As a metaphor it may have communicated clearly to its ancient Israelite audience, but it doesn’t communicate quite so clearly to us, clouded as it is with its ancient cultural bias. So as we read and seek to understand Hosea’s message in our day and age, we must extract the meaning from the metaphor and then, perhaps, cast the metaphor aside, separating the kernel of truth from the chaff of historical baggage.

In the modern world, marriage is not the patriarchal, male-dominated institution it was in Hosea’s time, but the metaphor can still work for us. In our Prayer Book, the meaning of marriage is summarized in the introductory comments with which the presiding minister begins the ceremony. We are told that it is a bond and covenant established by God in creation and that the union of the parties “in heart, body, and mind is intended by God for their mutual joy [and] for the help and comfort given one another in prosperity and adversity.” (BCP 1979, page 423)

Later in the service, just before the Nuptial Blessing is given, we pray for the couple that “each may be to the other a strength in need, a counselor in perplexity, a comfort in sorrow, and a companion in joy,” and that “their life together [may be] a sign of Christ’s love to this sinful and broken world, that unity may overcome estrangement, forgiveness heal guilt, and joy conquer despair.” (Page 429) In such a relationship neither party dominates the other, neither is submissive; it is a mutual and interdependent bond of covenant obligations, one to the other.

When Hosea’s prophetic metaphor is understood in these terms, it emphasizes that God is angry with God’s people for abandoning the covenant obligations they had to God, even as God remained faithful. What Hosea’s marriage metaphor communicates to us, as it did to his ancient audience, is that it is divine fidelity, not human inconstancy, that will ultimately save the relationship. It is God’s faithfulness, not our own, which prevails and redeems our relationship with God.

This is also the message of the author of the Letter to the Colossians, an epistle traditionally said to have been written by St. Paul, but which is now no longer believed to be of his authorship. The reason for that is in the very part of the text on which I want to focus our attention, the sentence where the author writes: “When you were buried with [Christ] in baptism, you were also raised with him through faith in the power of God, who raised him from the dead.” The author seems to echo Paul’s understanding of baptism in the Letter to the Romans, particularly a section we read every year on Easter Sunday. Paul writes, “Do you not know that all of us who have been baptized into Christ Jesus were baptized into his death? . . . . If we have been united with him in a death like his, we will certainly be united with him in a resurrection like his.” (6:3,5) The theology is similar, but note the significant shift: in Romans, Paul writes that we will be raised with Christ, whereas the author of Colossians asserts that our resurrection with Christ has already happened by reason of baptism. These two passages reflect the wonderful here-but-not-quite-here mysterious paradox of Christianity; we both celebrate the present reality of and anticipate the future consummation of our salvation in Christ. The victory has already been won, but not yet.

Now, what I really want to focus on is why our resurrection, our salvation, whether it is a present reality or something yet to occur, should happen at all! In Romans, Paul says that it happens “by the glory of the Father.” (v. 4) The author of Colossians asserts that it is “through faith in the power of God” according to our translation; that would seem to imply that our faith is somehow responsible for our salvation, that the means for our resurrection is our fidelity. But there is a growing body of scholarship which suggests that this is a misunderstanding of the original Greek of the text. The Greek is dia te pisteo te energeia tou theou . . . literally: “through the faith the working of God.” Traditional English translations add the preposition “in” into the interpretation which would imply that this powerful, operative faith is ours, but the Greek can also be understood to mean not “faith in” but rather “faith of” – in other words, it is God’s faith!

The 18th Century Lutheran translator Johann Albrecht Bengel suggested exactly this in his Annotations on the New Testament when he translated this text to say that our salvation, our resurrection comes about through faith which is a work of God. This text, he says, is “a remarkable expression: faith is of Divine operation.” (Gnomon of the New Testament, A. Fausset, tr., Clark:Edinburgh 1858, page 171, emphasis in original) Our resurrection with Christ is not brought about because of our faith; it is not because of us, or anything we do or believe! We are saved through the faithfulness of God who, by his glory and power, raised Christ from the dead.

It is also God’s faithfulness to which Jesus alludes in the parental metaphor which he uses in his instruction about prayer: “Is there anyone among you who, if your child asks for a fish, will give a snake instead of a fish? Or if the child asks for an egg, will give a scorpion? If you then, who are evil, know how to give good gifts to your children, how much more will the heavenly Father give the Holy Spirit to those who ask him!” God is the faithful parent who always responds when we ask, who is always there to be found when we search, who always opens the door when we knock. It is God’s faithfulness, not our own, which prevails and redeems our relationship with God.

On this we can rely; in this faithful God, we can have faith.

So let’s go back to Hosea’s marriage metaphor. The Lutheran Book of Worship, used by our brothers and sisters in the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America, with whom we enjoy a relationship of full communion, says this about marriage: “The Lord God in his goodness created us . . . and by the gift of marriage founded human community in a joy that begins now and is brought to perfection in the life to come. Because of sin, our age-old rebellion, the gladness of marriage can be overcast, and the gift of the family can become a burden. But because God, who established marriage, continues still to bless it with his abundant and ever-present support, we can be sustained in our weariness and have our joy restored.” (LBW 1978, page 203)

It is into the household of God, the community of joy restored, the covenant of mutual help and comfort sustained by the faithfulness of God, that we welcome Ryan George and Jacqueline Ann this morning. They (and we together with them) will make the statements of belief and the promises of action set out in the Baptismal Covenant (BCP 1979, pages 304-04), and they (and we) will try faithfully to keep them. Fortunately, however, it is God’s faithfulness, not theirs (nor ours), which will prevail and redeem them (and us), and their (and our) relationship with God.

Let us pray:

Almighty God, by our baptism into the death and resurrection of your Son Jesus Christ, you turn us from the old life of sin: Grant that we, being reborn to new life in him, may live in righteousness and holiness all our days; through Jesus Christ our Lord, who lives and reigns with you and the Holy Spirit, one God, now and for ever. Amen. (BCP 1979, page 254)

====================

A request to my readers: I’m trying to build the readership of this blog and I’d very much appreciate your help in doing so. If you find something here that is of value, please share it with others. If you are on Facebook, “like” the posts on your page so others can see them. If you are following me on Twitter, please “retweet” the notices of these meditations. If you have a blog of your own, please include mine in your links (a favor I will gladly reciprocate). Many thanks!

====================

Father Funston is the rector of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Medina, Ohio.

![]()

Does the name “Jesse Washington” mean anything to you? It’s unlikely that it does. If I tell you that Jesse Washington died in 1916 in Waco, Texas, would that spark any memory? Have you ever been taught about the incident in which Washington was killed? Have you ever heard of what came to be called “The Waco Horror?”

Does the name “Jesse Washington” mean anything to you? It’s unlikely that it does. If I tell you that Jesse Washington died in 1916 in Waco, Texas, would that spark any memory? Have you ever been taught about the incident in which Washington was killed? Have you ever heard of what came to be called “The Waco Horror?” Psalm 136 is twenty-six verses long. The second half of every single verse is the same: “For [God’s] steadfast love endures for ever.”

Psalm 136 is twenty-six verses long. The second half of every single verse is the same: “For [God’s] steadfast love endures for ever.”  I think I know what Paul is trying to say here, but I don’t like the way he’s saying it. I mean, I really have a theological issue with the assertion that “flesh and blood cannot inherit the kingdom of God.” I think the statement is just plain wrong. It states a dualism that relegates the material, specifically the human body, to realm of the damned, the unclean, the unworthy. In light of a creation story in which the Creator “saw everything that he had made [including that human flesh and blood], and indeed, it was very good,” I cannot accept the condemnation of our material being.

I think I know what Paul is trying to say here, but I don’t like the way he’s saying it. I mean, I really have a theological issue with the assertion that “flesh and blood cannot inherit the kingdom of God.” I think the statement is just plain wrong. It states a dualism that relegates the material, specifically the human body, to realm of the damned, the unclean, the unworthy. In light of a creation story in which the Creator “saw everything that he had made [including that human flesh and blood], and indeed, it was very good,” I cannot accept the condemnation of our material being. Two weeks before Easter I came down with the flu. I spent three days in bed with a high fever, a racking cough, and a good deal of body aches and pains. A friend who suffered the same illness (it’s gone around our town and several people have suffered through it) described the muscle pain as feeling as if one had been beaten up, thrown the ground, and kicked several times. It felt to me as if every square centimeter of connective tissue in my body was inflamed at the same time. (This is the first time in a couple of weeks or more that I’ve had enough morning energy to write anything after reading the daily lessons.)

Two weeks before Easter I came down with the flu. I spent three days in bed with a high fever, a racking cough, and a good deal of body aches and pains. A friend who suffered the same illness (it’s gone around our town and several people have suffered through it) described the muscle pain as feeling as if one had been beaten up, thrown the ground, and kicked several times. It felt to me as if every square centimeter of connective tissue in my body was inflamed at the same time. (This is the first time in a couple of weeks or more that I’ve had enough morning energy to write anything after reading the daily lessons.) Several days ago, as I was reading again the Easter story and the sections of the Holy Scriptures appointed for this year, I had the radio on and tuned to my favorite oldies station.

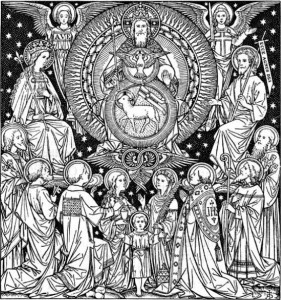

Several days ago, as I was reading again the Easter story and the sections of the Holy Scriptures appointed for this year, I had the radio on and tuned to my favorite oldies station. In the Eastern Orthodox tradition, icons of the Resurrection depict Christ rising from the tomb with a whole crowd of people. To one side of him crowned and haloed are King David and King Solomon; on the other, we see Abel the first martyr of creation carrying a shepherd’s crook and Moses the first prophet of the Old Covenant. Also present is John the Baptist, who is both the first prophet and the first martyr of the New Covenant. Beneath Christ’s feet, the gates of hell lie broken, often forming a cross. And from two tombs, Adam and Eve are rising, but not of their own accord; Jesus holds them by the wrists and is pulling them from their graves.

In the Eastern Orthodox tradition, icons of the Resurrection depict Christ rising from the tomb with a whole crowd of people. To one side of him crowned and haloed are King David and King Solomon; on the other, we see Abel the first martyr of creation carrying a shepherd’s crook and Moses the first prophet of the Old Covenant. Also present is John the Baptist, who is both the first prophet and the first martyr of the New Covenant. Beneath Christ’s feet, the gates of hell lie broken, often forming a cross. And from two tombs, Adam and Eve are rising, but not of their own accord; Jesus holds them by the wrists and is pulling them from their graves.  “Name this child.” That’s what I say to parents of infant baptismal candidates as I take their children from them. The words are not actually written in the baptismal service of The Book of Common Prayer as they are in some other traditions’ liturgies, but there is a rubric on page 307 that says, “Each candidate is presented by name to the Celebrant . . . .” so asking for the child’s name is a practical way of seeing that done. It’s practical, but it’s also a theological statement.

“Name this child.” That’s what I say to parents of infant baptismal candidates as I take their children from them. The words are not actually written in the baptismal service of The Book of Common Prayer as they are in some other traditions’ liturgies, but there is a rubric on page 307 that says, “Each candidate is presented by name to the Celebrant . . . .” so asking for the child’s name is a practical way of seeing that done. It’s practical, but it’s also a theological statement.  In the assembly of the elders of the people, the chief priests and the scribes, Jesus is asked, “Are you the Messiah?” and in response he gives vent to some very real human frustration.

In the assembly of the elders of the people, the chief priests and the scribes, Jesus is asked, “Are you the Messiah?” and in response he gives vent to some very real human frustration.  It’s Good Shepherd Sunday . . . the Fourth Sunday of the Easter Season is always Good Shepherd Sunday. Every year, regardless of which of the three years of the Lectionary cycle we are in, we hear some lessons which mention shepherds or lambs, and we recite the 23rd Psalm as the Gradual, and we sing every “Shepherd hymn” in the hymnal. I’ve been preaching Good Shepherd sermons for 25 years, so I pretty much thought this was going to be one of those Sundays when I could just “wing it” and preach extemporaneously.

It’s Good Shepherd Sunday . . . the Fourth Sunday of the Easter Season is always Good Shepherd Sunday. Every year, regardless of which of the three years of the Lectionary cycle we are in, we hear some lessons which mention shepherds or lambs, and we recite the 23rd Psalm as the Gradual, and we sing every “Shepherd hymn” in the hymnal. I’ve been preaching Good Shepherd sermons for 25 years, so I pretty much thought this was going to be one of those Sundays when I could just “wing it” and preach extemporaneously.  Several years ago, shortly after my mother died, my step-dad’s business partner also passed away leaving my step-dad to run the business they had created together. Now it is no insult to my step-dad, Stan, who had never before been a business owner, to say that he knew little or nothing about running a business. He’d been a tool-and-die man most of his working life with a brief foray into sales, but he’d never been in the “front office” and he’d certainly never been a manager or executive of any sort. Stan didn’t know accounts receivable from fish, and inventory control was a foreign language to him.

Several years ago, shortly after my mother died, my step-dad’s business partner also passed away leaving my step-dad to run the business they had created together. Now it is no insult to my step-dad, Stan, who had never before been a business owner, to say that he knew little or nothing about running a business. He’d been a tool-and-die man most of his working life with a brief foray into sales, but he’d never been in the “front office” and he’d certainly never been a manager or executive of any sort. Stan didn’t know accounts receivable from fish, and inventory control was a foreign language to him.