====================

This sermon was preached on Resurrection Sunday, March 31, 2013, at St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Medina, Ohio, where Fr. Funston is rector.

(Revised Common Lectionary, First Sunday of Easter: Isaiah 65:17-25; Psalm 118:1-2,14-24; 1 Corinthians 15:19-26; and John 20:1-18 . These lessons can be read at The Lectionary Page.)

====================

Make no mistake: if He rose at all

it was as His body;

if the cells’ dissolution did not reverse, the molecules

reknit, the amino acids rekindle,

the Church will fall.

So writes novelist and poet John Updike in the first of his Seven Stanzas at Easter from the collection Telephone Poles and Other Poems. Here is the rest of the poem:

It was not as the flowers,

each soft Spring recurrent;

it was not as His Spirit in the mouths and fuddled

eyes of the eleven apostles;

it was as His Flesh: ours.The same hinged thumbs and toes,

the same valved heart

that – pierced – died, withered, paused, and then

regathered out of enduring Might

new strength to enclose.Let us not mock God with metaphor,

analogy, sidestepping transcendence;

making of the event a parable, a sign painted in the

faded credulity of earlier ages:

let us walk through the door.The stone is rolled back, not papier-mache,

not a stone in a story,

but the vast rock of materiality that in the slow

grinding of time will eclipse for each of us

the wide light of day.And if we will have an angel at the tomb,

make it a real angel,

weighty with Max Planck’s quanta, vivid with hair,

opaque in the dawn light, robed in real linen

spun on a definite loom.Let us not seek to make it less monstrous,

for our own convenience, our own sense of beauty,

lest, awakened in one unthinkable hour, we are

embarrassed by the miracle,

and crushed by remonstrance.

“Let us not seek to make it less monstrous!” I love that line!

Only a poet like John Updike could use the word monstrous to describe the Resurrection of Christ and, in spite of its shock value, or perhaps because of it, it is the perfect word, an ambiguous word that captures the essence of the entire Palm Sunday – Maundy Thursday – Good Friday – Resurrection Day event. Monstrous can, and usually does, mean something like “frightful or hideous; extremely ugly; shocking or revolting; awful or horrible,” and those are certainly good words to describe the way the people of Jerusalem turned on Jesus, the way his disciple Judas betrayed him, the way his other followers denied and abandoned him, the way the authorities both Jewish and Roman abused and killed him. It was all monstrous; there’s no doubt about that!

Monstrous, however, can also mean “extraordinarily great; huge; immense; outrageous; overwhelming.” And those are superlative ways to describe the fact of Christ’s Resurrection from the dead! It is a huge thing! It is immense, outrageous, overwhelming! Yes, the Resurrection is monstrous!

I have been thinking a lot recently about two people who are hardly ever thought of in all the drama and majesty of Holy Week and Easter: one of them is mentioned briefly only by John in his story of Jesus’ Crucifixion; the other isn’t named at all. I refer to Mary and Joseph, Jesus’ mother and foster father.

Of course, we know nothing of Joseph during Jesus’ adult ministry; after that event in the Jerusalem Temple when Jesus was about 13, Joseph is never again mentioned in the Gospels. Some suppose this is because he had passed away, but I like to think that he was just back home in Nazareth working the family carpentry business, making tables and chairs, supervising construction of homes, building hope chests, keeping the family provided for so that Jesus could go about his ministry and Mary could accompany him.

Mary is mentioned in John’s story of the Crucifixion as standing at the foot of the cross and being entrusted by Jesus to the disciple whom he loved. And the legend from which we get the 14th Station of the Stations of the Cross, and which Michelangelo’s exquisitely beautiful Pieta depicts, is that when his body was removed from the cross she held him, dead, in her arms. But there is no mention of her or of Joseph at Jesus’ burial, nor are they mentioned in any of the accounts of Christ’s post-resurrection appearances.

That omission, for I am sure that is what it is, an omission, disturbs me. Yesterday, was the 55th anniversary of my father’s accidental death at the age of 39. His mother and father, my grandparents, were in their sixties when he died. One of my clearest memories of childhood is his funeral. I remember how, as we were leaving the graveside, my grandparents hung back, how they could not step away from nor turn their backs on the grave that held their child’s lifeless body. When, at last, they accepted my Uncle Scott’s physical encouragement to do so, my grandmother said to my mother, “A mother should not outlive her child.” She would know that feeling again just a few years later when my Uncle Scott died of cancer.

And my mother would know it, as well, when in 1993 my only sibling, my older brother Rick, died of brain cancer. I vividly remember doing exactly what my uncle had done, physically moving my mother and stepfather away from the grave, the grave they could not leave on their own. Later that day, my mother said to me, “You’re grandmother was right. A parent should not outlive her child.”

Having seen my grandparents and my parents at the graves of their children, I cannot believe that Mary and Joseph were not there when the stone was rolled into place, when Jesus was buried in that borrowed tomb.

Updike’s description of the Resurrection and his admonition to us, “Let us not seek to make it less monstrous,” so aptly describes the entire event of Holy Week and Easter, because we cannot appreciate the overwhelming wonder of the Resurrection, without taking into account the horror and ugliness of the whole thing, Judas’ betrayal, the other disciples abandonment, Peter’s denial, the trial before Pilate, Christ’s scourging and humiliation, his bitter agony on the Cross, his final self-emptying in death, and his burial at which I cannot but believe his mother and foster father were present. It is all monstrous; painful and ugly and awful in the first sense of that wonderfully ambiguous adjective.

I thought that I had some sense of that because I had witnessed my grandparents’ and my parents’ anguish at the deaths of their children; I thought I understood what old Simeon had said to Mary when Jesus was dedicated in the Temple as an infant, his disturbing prophecy, “A sword will pierce your own soul, too.” (Luke 2:35) I thought that I had understood all that until a couple of weeks ago.

As some of you know, two weeks ago Good Friday, sixteen days ago, our daughter disappeared. She stopped posting things to Facebook, which she had been in the habit of doing almost hourly from her cell phone. She stopped answering her cell phone; calls would go directly to voicemail. Her friends checked her home and found her car gone and no one there. She wasn’t at her place of work; she wasn’t at her school; she wasn’t at any of her usual hangouts. My wife, our son, our daughter-in-law, and several of our daughter’s friends looked everywhere they could think of in the area of St. Louis, Missouri, where her apartment is. I played the role of information central, receiving their reports and letting everyone know what everyone knew, which was nothing. We went to bed that night knowing nothing.

Family systems therapists have discovered that patterns of events run in families. Not just habits or ways of handling things, not just customs or traditions, but actual life events repeat from generation to generation. I went to bed convinced that the pattern of a child predeceasing his or her parents was playing out again. I knew in the very depths of my being that my daughter was dead.

Let me tell you, old Simeon in that Temple proved himself a master of understatement. That sword of grief does not simply pierce a parent’s soul; it rips the soul to shreds. That, I now know, is why my grandparents and my parents could not leave those graves, and that is why I cannot believe that Mary and Joseph were not there in that garden when Joseph of Arimathea and Nicodemus buried their child.

Now, lest you believe that this is a funeral oration rather than an Easter homily, let me assure you that our daughter is not dead! As it turned out (Thanks be to God!), she had gone to Kansas City on a personal errand and, while there, had become acutely ill and been admitted to a local hospital on an emergency basis. She had lost her cell phone and because she hadn’t memorized our telephone numbers, she couldn’t call us. (One of the dangers of cell phones, it turns out, is relying on its memory of stored numbers instead of one’s own memory!) On Saturday morning, through a friend, she got word to her mother about where she was, and then her mother called me. Our daughter is now out of the hospital, is back in St. Louis, and is back to her usual occupations. But I cannot tell you how relieved her mother and I were on that Saturday morning! All of the anguish and fear and sorrow and grief of the night before drained away. I cannot say that we were joyful or happy, but we were profoundly, overwhelmingly, monstrously relieved.

Which brings me back to Mary and Joseph and the first Easter morning . . . . I have an entirely new understanding of the Resurrection story. Preachers and theologians toss around a funny word to describe the way we view and interpret Holy Scripture. The word is hermeneutic. It means, basically, the method or principle through which we understand the text; it is the filter through which we appreciate its meaning. There are shared, intellectual hermeneutics, but there are also highly personal hermeneutics. I share my grandparents’ and my parents’ and my family’s recent experiences with you so that I can also share with you, and you can enter into, my new personal hermeneutic for grasping the impact of the Day of Christ’s Resurrection.

Just as I am puzzled by the absence of almost any mention of Mary and Joseph in the narrative of Christ’s death and burial, and I am astounded that there is no allusion to them in the Gospel accounts of that first Easter morning or any time after his Resurrection! The only word about either of them is in the first chapter of the Book of Acts and, again, it’s only Mary who gets mentioned. Luke, the author of Acts, says that following Christ’s Ascension forty days after his Resurrection the apostles “were constantly devoting themselves to prayer, together with certain women, including Mary the mother of Jesus, as well as his brothers.” (Acts 1:14) That’s it, that one mention! I find that astonishing! Apparently so have many Christians throughout the ages, because there is an extra-biblical tradition that the Virgin Mary was the first person to witness our Lord’s Resurrection.

The Golden Legend, which is a medieval collection of stories about the saints, says that the first appearance of the resurrected Christ on Easter Day was to the Virgin Mary:

It is believed to have taken place before all the others, although the evangelists say nothing about it.. . . . [I]f this is not to be believed, on the ground that no evangelist testifies to it . . . perish the thought that such a son would fail to honor such a mother by being so negligent! . . . Christ must first of all have made his mother happy over his resurrection, since she certainly grieved over his death more than the others. He would not have neglected his mother while he hastened to console others.

St. Ignatius of Antioch (1st C.) claimed it was so, as did St. Ambrose of Milan (4th C.), St. Paulinus of Nola (4th C.), the poet Sedulius (5th C.), St. Anselm of Canterbury (11th C.), St. Albertus Magnus (13th C.), St. Bernardino da Siena (15th C.), and the bible scholar Juan Maldonado (16th C.)

Most recently, the late Bishop of Rome, his Holiness John Paul II, in a general audience in 1997 expressed this opinion:

The Gospels mention various appearances of the risen Christ, but not a meeting between Jesus and his Mother. This silence must not lead to the conclusion that after the Resurrection Christ did not appear to Mary . . . . Indeed, it is legitimate to think that [his] Mother was probably the first person to whom the risen Jesus appeared. Could not Mary’s absence from the group of women who went to the tomb at dawn indicate that she had already met Jesus? This inference would also be confirmed by the fact that the first witnesses of the Resurrection, by Jesus’ will, were the women who had remained faithful at the foot of the Cross and therefore were more steadfast in faith. (Gen. Aud., Wednesday, 21 May 1997)

I cannot but believe that the Risen Christ appeared to Mary and Joseph (if he was present as I prefer to think he was), and that they would have been at least as profoundly, overwhelmingly, monstrously relieved as my wife and I were two weeks ago yesterday, if not more so!

So here’s my new thought, my new hermeneutic of Easter Day. I think that the overwhelming initial response, especially of Mary and Joseph, but also of Mary Magdalene, of Peter, of the disciple whom Jesus loved, of all the others, to the fact of Jesus’ Resurrection was not, as we are usually told at Easter Services, joyfulness! I think it was relief. The dictionary defines relief as “alleviation of pain, as the easing of anxiety, as deliverance from distress.” This is the appropriate experience and emotion of Easter Day, profound relief, not immediate joy or gladness; I think that comes later in the Easter Season and that it comes later in life as we live out our Easter faith. But in the immediate aftermath of the monstrous-ness of Holy Week, in the wake of the horrible ugliness of death, Christ’s or anyone else’s, one is simply not ready to be jubilant and happy. In the face of our own sinfulness and spiritual dysfunction, we are not ready for joy and gladness. But the fact of Christ’s Resurrection relieves us of grief and sorrow; it relieves us of sin and death. The experience and impact of Easter Day is one of profound, overwhelming, (one might even say) monstrous relief.

Perhaps that is why Jesus stuck around for forty days, to continually reassure and sustain the disciples in their relief from fear and sorrow and grief, so that they could move into joy and gladness as time went on. Perhaps that is why Easter is not a single day, but a season of fifty days, so that as it progresses we can . . . like Mary and Joseph, like the Magdalen and Peter, like the disciple whom Jesus loved and all the apostles . . . move from relief into Resurrection joy, so that it provides a pattern with which we can handle the inevitable losses in our lives. As life goes on and as the victory of life over death sinks in, Easter relief grows into Easter joy, something that propels us toward action and compels us to invite others into the Resurrected life of our Risen Lord.

As Christians, we have access through the relief of Christ’s Resurrection into a joy that is unshakable. We must remember, however, that joy is really not an emotion — it is a virtue. Easter joy does not mean being happy all the time or being fine when times are difficult; Easter joy means being sustained by the power of the Resurrection. What Easter joy means is that in the depths of our being, despite the circumstances we may face, despite any fears we may have, despite whatever may be tearing up our souls, despite whatever sin or spiritual malaise we may be in, we are able to get through them, to let go of them, and to find relief and eternal life in the Resurrected Christ, a life into which we invite others.

John tells us that on that first Easter morning, when Jesus called the Magdalen by name, “she turned and said to him in Hebrew, ‘Rabbouni!’ (which means Teacher).” I do not hear joy and happiness in the voice of this woman who had just been weeping in grief and confusion at his grave; I do hear relief. She was so comforted that she grabbed on to him, but he said to her, “Do not hold on to me . . . . .” It has been said that joy comes from letting go — letting go of our attachments, letting go of any thoughts that the present moment should or even could be different than it is, letting go of our expectations. Joy is the virtue of celebrating present, of living in the moment, something to which we come through a process of detachment and release. Resurrection Day is not the end of the process; it is the beginning. “Do not hold on to me,” Jesus said to Mary Magdalen, “But go to my brothers . . . .” Go and invite them into the outrageous reality of which you are now a part.

Easter Day brings relief, overwhelming relief! Through that relief we are able to let go, to release our fears, our griefs, our worries, and our sorrows with absolute abandon, to be completely freed of our sinfulness! In letting go as the Easter Season and as our Easter faith progress, we ultimately find joy, unutterably ecstatic joy, huge, overwhelming, outrageous joy into which we are compelled to invite others!

“Let us not seek to make it less monstrous!”

Alleluia! Christ is risen!

====================

A request to my readers: I’m trying to build the readership of this blog and I’d very much appreciate your help in doing so. If you find something here that is of value, please share it with others. If you are on Facebook, “like” the posts on your page so others can see them. If you are following me on Twitter, please “retweet” the notices of these meditations. If you have a blog of your own, please include mine in your links (a favor I will gladly reciprocate). Many thanks!

====================

Father Funston is the rector of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Medina, Ohio.

In The Book of Common Prayer on page 264 you’ll find the beginning of the liturgy for Ash Wednesday. If you were here on that day which marks the beginning of this season we call Lent, or in another church to be marked on your forehead with the cross of ashes, to be reminded of your mortality with the familiar words, “Remember you are dust, and to dust you will return,” you will also have heard the Lenten admonition which the presiding priest reads at each Ash Wednesday service. It begins at the bottom of that page and comes in the service after the reading of the lessons of the day and the preaching of the sermon.

In The Book of Common Prayer on page 264 you’ll find the beginning of the liturgy for Ash Wednesday. If you were here on that day which marks the beginning of this season we call Lent, or in another church to be marked on your forehead with the cross of ashes, to be reminded of your mortality with the familiar words, “Remember you are dust, and to dust you will return,” you will also have heard the Lenten admonition which the presiding priest reads at each Ash Wednesday service. It begins at the bottom of that page and comes in the service after the reading of the lessons of the day and the preaching of the sermon. Today is the Third Sunday of Advent; in the tradition of the church it is known as Gaudete Sunday, Latin for “Rejoicing Sunday” so named because of the medieval introit to the Mass, “Gaudete in Domino semper: iterum dico, gaudete”, St. Paul’s words in the Letter to the Philippians, “Rejoice in the Lord always: again I say rejoice.” (4:4) (A reading from that very portion of Paul’s letter is this year’s epistle lesson for the Eucharist today; we will hear and consider those words at church this morning.)

Today is the Third Sunday of Advent; in the tradition of the church it is known as Gaudete Sunday, Latin for “Rejoicing Sunday” so named because of the medieval introit to the Mass, “Gaudete in Domino semper: iterum dico, gaudete”, St. Paul’s words in the Letter to the Philippians, “Rejoice in the Lord always: again I say rejoice.” (4:4) (A reading from that very portion of Paul’s letter is this year’s epistle lesson for the Eucharist today; we will hear and consider those words at church this morning.) I hadn’t really planned to do a sermon series about my childhood summers spent with Edgar and Edna Funston, but these “I am” statements of Jesus from the Fourth Gospel keep taking me back there, so once again . . . a story from Winfield, Kansas, fifty years ago.

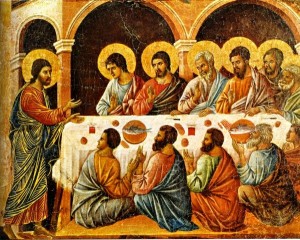

I hadn’t really planned to do a sermon series about my childhood summers spent with Edgar and Edna Funston, but these “I am” statements of Jesus from the Fourth Gospel keep taking me back there, so once again . . . a story from Winfield, Kansas, fifty years ago. I have to admit that I would be hard-pressed to choose one of the many post-resurrection appearances of Christ as my favorite. Each one recorded in Scripture is so full of vivid imagery and meaning that it would be nearly impossible to put one above another … having said that, however, I also have to admit an especial fondness for the one described here by Luke.

I have to admit that I would be hard-pressed to choose one of the many post-resurrection appearances of Christ as my favorite. Each one recorded in Scripture is so full of vivid imagery and meaning that it would be nearly impossible to put one above another … having said that, however, I also have to admit an especial fondness for the one described here by Luke.  Some time in the late Fourth Century, St. John Chrysostom, Archbishop of Constantinople and an important Early Church Father known for his eloquence in preaching and public speaking (hence, the surname Chrysostom which means “golden-mouthed”), preached this sermon on Easter.

Some time in the late Fourth Century, St. John Chrysostom, Archbishop of Constantinople and an important Early Church Father known for his eloquence in preaching and public speaking (hence, the surname Chrysostom which means “golden-mouthed”), preached this sermon on Easter.  Something strange is happening – there is a great silence on earth today, a great silence and stillness. The whole earth keeps silence because the King is asleep. The earth trembled and is still because God has fallen asleep in the flesh and he has raised up all who have slept ever since the world began. God has died in the flesh and hell trembles with fear.

Something strange is happening – there is a great silence on earth today, a great silence and stillness. The whole earth keeps silence because the King is asleep. The earth trembled and is still because God has fallen asleep in the flesh and he has raised up all who have slept ever since the world began. God has died in the flesh and hell trembles with fear. Act One, Scene One – Location: an upper room somewhere in Jerusalem.

Act One, Scene One – Location: an upper room somewhere in Jerusalem.