====================

This sermon was preached on the First Sunday in Lent, March 9, 2014, at St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Medina, Ohio, where Fr. Funston is rector.

(The lessons for the day were: Genesis 2:15-17,3:1-7; Psalm 32; Romans 5:12-19; and Matthew 4:1-11. These lessons can be read at The Lectionary Page.)

====================

Today, as we step further into the season of Lent, this season of self-examination when we liturgically join Jesus for his forty days in the desert, we are treated to what is traditionally known as the “Fall of Man.” Genesis, chapters 2 and 3 set out the Bible’s first story of human temptation and the first act of human disobedience in the garden of Eden, brilliantly portrayed by the Victorian-era lithographer Max Klinger in the etching on the cover of your bulletin in which the serpent presents Eve not just with an apple but with a mirror, a looking glass in which to examine herself.

Today, as we step further into the season of Lent, this season of self-examination when we liturgically join Jesus for his forty days in the desert, we are treated to what is traditionally known as the “Fall of Man.” Genesis, chapters 2 and 3 set out the Bible’s first story of human temptation and the first act of human disobedience in the garden of Eden, brilliantly portrayed by the Victorian-era lithographer Max Klinger in the etching on the cover of your bulletin in which the serpent presents Eve not just with an apple but with a mirror, a looking glass in which to examine herself.

The popular understanding of this story is that it explains why human beings do not live in a world of perfect comfort, why there is evil in the world, blaming it all on the Devil and on the weakness of the woman. That popular interpretation, however, is based on some frankly erroneous assumptions.

First, that God created an absolutely perfect and static world.

Well, that’s clearly wrong. The world that God has created in the Genesis accounts includes the raging sea, which has been divided into two waters – the water above the firmament and the water below the firmament. In the theological and cosmological understanding of the ancient middle eastern world, the sea was the place of chaos; God’s Spirit moves over and subdues that chaos, declaring to it (as the voice from the whirlwind in the Book of Job puts it), “Thus far shall you come, and no farther, and here shall your proud waves be stopped.” (Job 38:11) Far from static and far from perfect, God’s world contains the chaotic, the unsettled, and the creative.

And let’s not forget the serpent who “was more crafty than any other wild animal that the Lord God had made;” I’ll come back to him in a moment. He’s a part of this creation, which clearly is neither perfect and static.

The second erroneous assumption often made is that Eden was a luxurious paradise in which humans lived with no responsibilities.

We can only have that incorrect understanding if we overlook the first sentence of our reading: “The Lord God took the man and put him in the garden of Eden to till it and keep it.” (Gen. 2:15, emphasis added) The humans in this garden had work to do! One might quibble with the translation, however.

The traditional rendering of the Hebrew word ‘abad as “till” reflects the agriculturally based culture of 17th Century England; the word has been rendered in this manner (or by the equivalent word “cultivate”) since the Authorized Version of King James I & VI. But the Hebrew is better translated (and more frequently rendered throughout the rest of the Old Testament) as “serve;” it is the root from which the word “slave” derives. The distinction is significant. “Tilling” implies some control of the garden and suggests that the human can make it better or more productive. But the humans were not, in fact, in control at all; they were to be the servants of the soil, working in partnership with it to make the garden fruitful.

And then there’s the word translated “keep” — shamar in Hebrew. In common modern English, “keep” has the sense of ownership, of having a claim on the garden, the Hebrew really means “to keep safe, to guard, or to protect.” The humans were to serve the garden and to protect that which they were meant to serve. They were given neither control nor ownership.

But whether to cultivate and maintain or to serve and protect, the humans were given work and responsibility in this garden. No luxurious paradise, this Eden.

The third incorrect assumption is that the serpent was evil.

Actually, this error is a bit more serious than that. This mistake, in fact, holds that the serpent was Satan intent on bringing evil into God’s perfect creation, one of the central points of the popular interpretation.

But, again, one has to ignore the very words of the text to believe that about the serpent. As I pointed out a moment ago, the serpent is described as a “wild animal that the Lord God had made.” The serpent is a very clever and very conversational animal, but that’s all – an animal. This crafty old snake is just one of God’s own creatures who simply poses some questions and offers some alternative explanations about God to the humans who could have, if they’d chosen to do so, told the serpent that he was full of it and asked him to please go away.

The wily serpent is, one commentator has suggested, a “metaphor, representing anything in God’s good creation that is able to facilitate options for human will and action.” God has created a world in which human beings have choices, alternatives to the will of God. And in this world human choices count; our relationship with God is not predetermined and our response to God is neither coerced nor inevitable. The story reveals that there was and is something in human nature that resonates to the suggestion of suspicion that the serpent offered about the words and actions of God, and we’ll come back to that in a moment. So the serpent is not Satan and he does not bring evil into the picture; he’s a clever animal who introduces the humans to wariness and skepticism.

The fourth traditional, but wrong, supposition is that it was Eve alone who succumbed to temptation and so she alone is responsible for bringing sin into the world.

When we listen to people discuss this story, the impression is that they believe that Eve was all by herself, had this conversation with the snake, ate the apple, gained for herself the “knowledge of good and evil” (more needs to be said about that, by the way), and then went and tempted Adam to do the same. Nothing could be further from the truth!

The plain meaning of the words is that Adam was there all along: “She took of its fruit and ate; and she also gave some to her husband, who was with her, and he ate.” Just as, at any point in the conversation, the humans could have told the snake to get lost, Adam could have spoken up, at any point, and suggested to Eve that she discontinue the dialogue with the snake. But he doesn’t. While Eve converses with the serpent, expressing her knowledge of God’s command, Adam just stands there silent, and then he eats with no objection.

And take note! That’s when things start to happen. It isn’t until both of them have consumed the fruit that “the eyes of both were opened, and they knew that they were naked . . . .”

That last simply wrong understanding is that the “knowledge of good and evil” has something to do with morality.

It doesn’t. Hadda-‘at towb wara’ is simply idiomatic Hebrew for knowledge of everything; saying “good and bad” in Hebrew is like saying “lock, stock, and barrel” in American English.

The two most important words spoken by the crafty serpent are “God knows,” because they arouse suspicion. They carry a corollary suggestion: “God knows . . . and you don’t.” God, the snake hints, has not told you the full truth. And the surprising thing is that the serpent is telling the truth! The serpent may not tell the whole truth, but then neither has God.

Which brings us back to the question of suspicion. At its deepest level the issue of knowledge, the knowledge of good and evil, the knowledge of everything, becomes an issue of trust. Can human beings trust God? Can Adam and Eve, can any human being, trust that God has our best interests at heart?

Until they ate of that fruit, Adam and Eve were oblivious to their nakedness; after eating it, they find themselves hiding from God out of shame. Scholars and sages from the ancient Chinese philosopher Confucius to the 20th Century psychologist Eric Erickson have noted the intimate linkage between mistrust and shame. The moment Adam and Eve ate from the fruit of the tree of knowledge of everything, they began to experience a profound sense of vulnerability, a sense of distrust of God, perhaps even a distrust of one another and of the serpent with whom they (well, Eve anyway) have been conversing like old friends.

We all know what happens next, right? God shows up and asks what’s happened. Adam points to Eve, “She did it. She made me eat the fruit.” And Eve points to the snake, “The serpent tricked me!” This sense of shame and mistrust is grounded in their failure to fully realize that they were made in the image and likeness of God.

That is why I put that Victorian etching by Max Klinger on the cover of our bulletins this week. It is one of six panels in a work made by Klinger in 1880 entitled Eva und die Zukunft (“Eve and the Future”). In it the snake is holding a mirror and Eve, standing on tip-toe, is viewing her own image. The serpent’s appeal is to her (and to Adam’s) vanity. “God knows . . . and you don’t.” Invited (as we are during Lent) to examine herself, she cannot see the image of God in the mirror; she can see only her own suspicious visage.

So if this story is the story of a “fall” or “falling,” what sort of falling is it? Is it a falling down from some supposedly higher level of perfection? I think not. The initial creation was not a set-piece of static perfection. Is it a falling up into some greater human maturity as Iranaeus and other early theologians suggested, a leaving behind of some childlike innocence? In the story, the human beings, before the fruit, aren’t really presented as childlike or innocent, and afterwards Adam and Eve certainly don’t exhibit much in the way of adult maturity when confronted by God. So, I don’t really believe that interpretation works either.

The Lutheran theologian Terrence Fretheim has suggested that if this is the story of a “falling” it is a “falling out,” the story of a breach in relationship leading (as the rest of the Bible clearly demonstrates) to estrangement, alienation, separation, and displacement, an ever-increasing distancing of human beings from Eden, from each other, and ultimately from God.

That suspicious alienation is symbolized by the clothing Adam and Eve make for themselves: “they sewed fig leaves together and made loincloths for themselves.” As the ancient Hebrews knew all too well, the leaves of Mediterranean fig would not make a particularly comfortable garment; they have a rather rough and sandpaper texture and their underside is covered with fine spiny “hairs”! Those loincloths would have been scratchy and prickly and uncomfortable — a great metaphor for a relationship broken by distrust and shame.

Which brings us to the Gospel lesson.

The snake in the Genesis story may not have been Satan, but here he is at the beginning of our Lord’s ministry and he’s doing with Jesus exactly what the serpent did with Eve; he’s appealing to his vanity. “Are you the son of God? Well, then, act like it! Show these people! Do something really incredible — turn stones into bread, throw yourself off the Temple steeple, rule the world!”

Jesus, however, turns each temptation aside with a quotation from Scripture. Each is different, but each of his responses boils down to the same thing – “I trust God.” And his life and his gospel will bear that out even to the end. Even then, in the most painful of circumstances when death is imminent, he will live out that trust: “Not my will but yours” (Luke 22:42) . . . “Into your hands I commend my spirit” (Luke 23:46). And, in the end and for eternity, he is clothed as John of Patmos saw him and reported in the Book of Revelation, in a flowing white robe of righteousness, crowned with many crowns, and seated at the right hand of God.

“Great are the tribulations of the wicked,” says our psalm today . . . their tribulation is like wearing a rough and scratchy garment of fig leaves . . . “but mercy embraces those who trust in the Lord.”

In this season of self-examination, in we which are asked to look at ourselves in a spiritual looking glass, like Eve’s mirror in Klinger’s etching, we must ask ourselves the question, “Which is it to be for us?” The rough, painful garment of alienation, or the flowing robes of mercy and righteousness?

We live in a world in which we have choices, and our choices count. Which is it to be? Do you trust God? Amen.

====================

A request to my readers: I’m trying to build the readership of this blog and I’d very much appreciate your help in doing so. If you find something here that is of value, please share it with others. If you are on Facebook, “like” the posts on your page so others can see them. If you are following me on Twitter, please “retweet” the notices of these meditations. If you have a blog of your own, please include mine in your links (a favor I will gladly reciprocate). Many thanks!

====================

Father Funston is the rector of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Medina, Ohio.

This may be the simplest, truest, most profound thing Paul ever wrote. No flowery language, no showing of his erudition and knowledge of the Hebrew Scriptures or of Greek philosophy, no convoluted logic, no run-on sentences. Just a simple declaration: if you are in litigation, you’ve already lost.

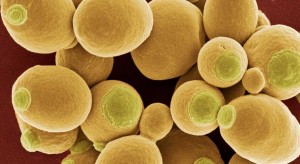

This may be the simplest, truest, most profound thing Paul ever wrote. No flowery language, no showing of his erudition and knowledge of the Hebrew Scriptures or of Greek philosophy, no convoluted logic, no run-on sentences. Just a simple declaration: if you are in litigation, you’ve already lost. Paul uses the metaphor of yeast in a negative way making it symbolize sin and corruption. In the letter to the Galatians, he uses it in a similar manner in an aside about the few who have “prevented you from obeying the truth,” saying, “A little yeast leavens the whole batch of dough.” (Gal. 5:7,9)

Paul uses the metaphor of yeast in a negative way making it symbolize sin and corruption. In the letter to the Galatians, he uses it in a similar manner in an aside about the few who have “prevented you from obeying the truth,” saying, “A little yeast leavens the whole batch of dough.” (Gal. 5:7,9) In the Education for Ministry (“EfM”)

In the Education for Ministry (“EfM”) Gregory of Nyssa, one of the Cappadocian Fathers, is supposed to have said, “Concepts create idols; only wonder comprehends anything. People kill one another over concepts. Wonder makes us fall to our knees.” I think that pretty much describes what is going on in today’s Gospel lesson, and pretty much describes what has become of conversation and discussion between groups in our society. The Pharisees and the Herodians, who disagreed with one another about nearly everything, could nonetheless come together and plot to kill Jesus because his words and actions threatened both of their conceptual frameworks. They had to defend their concepts against the wonder of healing, even if it meant killing.

Gregory of Nyssa, one of the Cappadocian Fathers, is supposed to have said, “Concepts create idols; only wonder comprehends anything. People kill one another over concepts. Wonder makes us fall to our knees.” I think that pretty much describes what is going on in today’s Gospel lesson, and pretty much describes what has become of conversation and discussion between groups in our society. The Pharisees and the Herodians, who disagreed with one another about nearly everything, could nonetheless come together and plot to kill Jesus because his words and actions threatened both of their conceptual frameworks. They had to defend their concepts against the wonder of healing, even if it meant killing. I remember preaching on this text some years ago and doing a lot of research into the meaning of “new wine” as used in the Bible (tirowsh in Hebrew, oinon neon in Greek) — whether it meant fermented wine or yet-to-be-fermented newly-crushed grape juice. There is a lot of differing scholarship on the issue, both among Biblical scholars and oenologists. I came to the conclusion that all of that scholarship is an interesting waste of time. None of it matters to Jesus’ meaning in using this metaphor for the spiritual life.

I remember preaching on this text some years ago and doing a lot of research into the meaning of “new wine” as used in the Bible (tirowsh in Hebrew, oinon neon in Greek) — whether it meant fermented wine or yet-to-be-fermented newly-crushed grape juice. There is a lot of differing scholarship on the issue, both among Biblical scholars and oenologists. I came to the conclusion that all of that scholarship is an interesting waste of time. None of it matters to Jesus’ meaning in using this metaphor for the spiritual life. It’s a familiar story. A paralyzed man on a pallet comes to Jesus carried by his friends. They can’t get by the crowd, so they cut a hole in the roof of the house where Jesus is staying. (The first verse of the chapter says “he was at home” in Capernaum. That’s an interesting thing to say of someone who “has nowhere to lay his head,” [Matt. 8:20] but I don’t want to be distracted by that this morning.) The man on his mat is lowered through the hole and Jesus heals him. A pretty straightforward story of a miracle healing.

It’s a familiar story. A paralyzed man on a pallet comes to Jesus carried by his friends. They can’t get by the crowd, so they cut a hole in the roof of the house where Jesus is staying. (The first verse of the chapter says “he was at home” in Capernaum. That’s an interesting thing to say of someone who “has nowhere to lay his head,” [Matt. 8:20] but I don’t want to be distracted by that this morning.) The man on his mat is lowered through the hole and Jesus heals him. A pretty straightforward story of a miracle healing. I’m mentoring a study group in my parish, eight well-educated adults seeking to better understand their faith. We’re using some academic materials from a program well-known to Episcopalians. At our last meeting, nearly all of them commented on and complained about the “high falutin'” academic language used by some of our authors. I thought of that as I read Paul describing his missionary efforts as not proclaimed “in lofty words or wisdom.”

I’m mentoring a study group in my parish, eight well-educated adults seeking to better understand their faith. We’re using some academic materials from a program well-known to Episcopalians. At our last meeting, nearly all of them commented on and complained about the “high falutin'” academic language used by some of our authors. I thought of that as I read Paul describing his missionary efforts as not proclaimed “in lofty words or wisdom.” The religion vs. science debate is heating up! Bill Nye the Science Guy recently debated Ken Ham, the founder of a “creation science” museum in Kentucky; they made headlines but not a lot of progress in resolving the phony conflict. Sunday night Neil deGrasse Tyson premiered his reboot of Carl Sagan’s classic Cosmos series, which included potshots at religious certainty including a very amateurish looking cartoon about Giordano Bruno which was, at best, inaccurate and, at worst, dishonest. (There’s been a lot of discussion among my Facebook friends about that.) I hope the series improves and doesn’t become a polemic against religion; the Sagan original certainly never was.

The religion vs. science debate is heating up! Bill Nye the Science Guy recently debated Ken Ham, the founder of a “creation science” museum in Kentucky; they made headlines but not a lot of progress in resolving the phony conflict. Sunday night Neil deGrasse Tyson premiered his reboot of Carl Sagan’s classic Cosmos series, which included potshots at religious certainty including a very amateurish looking cartoon about Giordano Bruno which was, at best, inaccurate and, at worst, dishonest. (There’s been a lot of discussion among my Facebook friends about that.) I hope the series improves and doesn’t become a polemic against religion; the Sagan original certainly never was. Jesus’ time of temptation in the desert is related by each of the Synoptic Gospels. Luke and Matthew give us a detailed account, noting that Satan tries to get Jesus to (a) turn stones into bread, (b) throw himself from the pinnacle of the Temple so as to demonstrate his power over the angels, and (c) worship Satan who promises him world domination. (We heard Matthew’s version on Sunday morning.)

Jesus’ time of temptation in the desert is related by each of the Synoptic Gospels. Luke and Matthew give us a detailed account, noting that Satan tries to get Jesus to (a) turn stones into bread, (b) throw himself from the pinnacle of the Temple so as to demonstrate his power over the angels, and (c) worship Satan who promises him world domination. (We heard Matthew’s version on Sunday morning.) Today, as we step further into the season of Lent, this season of self-examination when we liturgically join Jesus for his forty days in the desert, we are treated to what is traditionally known as the “Fall of Man.” Genesis, chapters 2 and 3 set out the Bible’s first story of human temptation and the first act of human disobedience in the garden of Eden, brilliantly portrayed by the Victorian-era lithographer Max Klinger in the etching on the cover of your bulletin in which the serpent presents Eve not just with an apple but with a mirror, a looking glass in which to examine herself.

Today, as we step further into the season of Lent, this season of self-examination when we liturgically join Jesus for his forty days in the desert, we are treated to what is traditionally known as the “Fall of Man.” Genesis, chapters 2 and 3 set out the Bible’s first story of human temptation and the first act of human disobedience in the garden of Eden, brilliantly portrayed by the Victorian-era lithographer Max Klinger in the etching on the cover of your bulletin in which the serpent presents Eve not just with an apple but with a mirror, a looking glass in which to examine herself.