====================

This sermon was preached on the Seventh Sunday after Epiphany, February 23, 2014, at St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Medina, Ohio, where Fr. Funston is rector.

(The lessons for the day were: Leviticus 19:1-2,9-18; Psalm 119:33-40; 1 Corinthians 3:10-11,16-23; and Matthew 5:38-48. These lessons can be read at The Lectionary Page.)

====================

Jesus doesn’t ask much, does he? Only perfection! “Be perfect,” he tells us, “as your heavenly Father is perfect.” Of course, Jesus is simply echoing the words Moses spoke on God’s behalf delivering the Law to the Hebrews: “You shall be holy, for I the Lord your God am holy.” What can this mean? How can we be expected to be perfect and holy like God? How can we do that, especially when both Moses and Jesus insist that that means, among other things, loving our enemies, not seeking redress, not holding a grudge, and not getting that to which we are sure we are entitled?

Jesus doesn’t ask much, does he? Only perfection! “Be perfect,” he tells us, “as your heavenly Father is perfect.” Of course, Jesus is simply echoing the words Moses spoke on God’s behalf delivering the Law to the Hebrews: “You shall be holy, for I the Lord your God am holy.” What can this mean? How can we be expected to be perfect and holy like God? How can we do that, especially when both Moses and Jesus insist that that means, among other things, loving our enemies, not seeking redress, not holding a grudge, and not getting that to which we are sure we are entitled?

Let’s first be certain that we know what we’re talking about! Let’s remember that these English words are translations of ancient Hebrew and biblical Greek, and that there may be connotations and nuances in those older languages that the English interpretations obscure.

The Hebrew in our reading from Leviticus is qadowsh and is derived from a root word meaning “set apart” (qadash). This, of course, was the purpose of the Law which God, through Moses, was giving to the Hebrews: it was to set them apart from other nations, other peoples. They were to be consecrated to God as a “holy nation” – a nation separated from the rest of humankind for a God’s special purposes.

God, through Moses and then repeatedly through the prophets, makes it clear that this does not mean that they are in any way better than other nations; they are simply different in that they will be used by God to accomplish God’s purposes. The prophet Amos, for example, reminded the Israelites that God had relationships with other nations: “Are you not like the Ethiopians to me, O people of Israel? says the Lord. Did I not bring Israel up from the land of Egypt, and the Philistines from Caphtor, and the Arameans from Kir?” (Amos 9:7)

The modern Orthodox Jewish view is that God chooses and sets apart many nations for differing purposes. The former Chief Rabbi of Great Britain, Immanuel Jakobovits, expressed it this way:

I believe that every people—and indeed, in a more limited way, every individual—is “chosen” or destined for some distinct purpose in advancing the designs of Providence. Only, some fulfill their mission and others do not. Maybe the Greeks were chosen for their unique contributions to art and philosophy, the Romans for their pioneering services in law and government, the British for bringing parliamentary rule into the world, and the Americans for piloting democracy in a pluralistic society. The Jews were chosen by God to be “peculiar unto Me” as the pioneers of religion and morality; that was and is their national purpose. (Commentary Magazine, August, 1966)

So this is what “holiness” means in our reading from Leviticus – to be set apart for God’s use in a particular way. It does not mean that the ancient Jews, nor we as the grafted-on “new Israel,” are expected to be God-like or sacred (whatever that means) or divine or particularly righteous or pure. It means, rather, that we are to be prepared, like a tool is prepared, to be used for God’s purposes.

In echoing Moses, however, Jesus chose to use another word, the word perfect. In the koine Greek of the New Testament, the word is teleios which signifies wholeness and completion, something brought to its intended end; it derives from a word meaning “the end” (telos) which carries with it a nuanced suggestion of a goal or a purpose. It is not identical to the Hebrew word used by Moses, but it carries much of the same implications. Jesus is not admonishing his hearers, then or now, to some sort of moral perfectionism, but rather to becoming what God has intended, to accomplishing one’s God-given purpose.

And so the question for us in response both to Leviticus and to Matthew’s Gospel is, “How do we do this? How can we be holy as God is holy? How can we be perfect as the Father is perfect?” We find the answer close at hand both in God’s giving of the Law and in Christ’s Sermon on the Mount.

The Levitical admonition to holiness is followed by several exemplary commandments, none of which are particularly religious! Leave something in your fields for the hungry to glean. Don’t lie to one another. Don’t defraud one another. Don’t steal from each other. Don’t mistreat the handicapped. Don’t be partial in your judgments. Don’t hate anyone or seek vengeance or even bear a grudge. That’s what holiness is; that’s what being set apart for God’s purposes is.

In the section of the Sermon on the Mount in today’s Gospel, Jesus continues with the rhetorical form he began in last week’s Gospel reading, the antitheses in which he contrasts the Law with his own teaching: “You have heard it said . . . but I say to you . . . .” You have heard the rule of justice, “an eye for an eye,” but I say to you, “Don’t insist on it. In fact, offer more. If you’re struck on one cheek, offer the other. If someone takes your cloak, give them your shirt, too. If you are pressed into service to carry a burden, carry it twice the distance.” You have heard it said, “Love your neighbor and hate your enemy” . . . . (Now, that one puzzles the scholars because although the Law does say, “You shall love your neighbor as yourself,” there is no commandment to hate one’s enemy. There are plenty of Old Testament examples of hating one’s enemy, but no commandment along those lines. In any event . . . .) You have heard it said, “Love your neighbor and hate your enemy,” but I say to you, “Love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you.” Why? Because God sends rain on the righteous and the unrighteous alike; God gives sunshine to both the good and the evil. God treats everyone impartially – and so should you. God is good to everyone impartially – and so should you be. That’s what it means to be perfect, to be whole and complete and living according to God’s purposes.

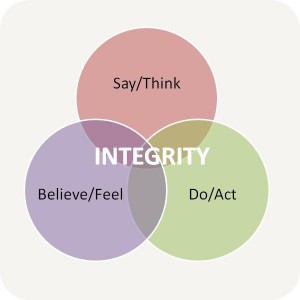

Another word for this is integrity. Integrity is that sort of wholeness that we experience or perceive in someone when their life is integrated – when who they are matches what they do. And more than that it’s that wholeness that we sense when a person not only “practices what they preach,” but when it all seems to flow from the very core of their being, when their preaching and their practice all seem to be in accord with God’s purpose for them. When we meet such a person, say for example Jesus, we know that they have no trouble forgiving their enemies and praying for their persecutors, don’t we? We’re sure of it!

So, how do we live an integrated life? How do we live with integrity? It’s really easy for a preacher to stand here and tell you to do that by imitating Christ, by living out God’s generous and unrestricted grace, mercy and love in all your relationships, with friend and foe alike. But that just begs the question! That’s just saying, “Live with integrity by living with integrity” and it’s not fair for a preacher to do that because we all know that there are times when being gracious and merciful and loving just isn’t all that easy, such as those times when we are called to love our enemies and those who do us wrong.

Frederick Buechner, the great Presbyterian story teller, wrote about this in his book Whistling in the Dark in an essay entitled Enemy:

Cain hated Abel for standing higher in God’s esteem than he felt he himself did, so he killed him. King Saul hated David for stealing the hearts of the people with his winning ways and tried to kill him every chance he got. Saul of Tarsus hated the followers of Jesus because he thought they were blasphemers and heretics and made a career of rounding them up so they could be stoned to death like Stephen. By and large most of us don’t have enemies like that anymore, and in a way it’s a pity.

It would be pleasant to think it’s because we’re more civilized nowadays, but maybe it’s only because we’re less honest, open, brave. We tend to avoid fiery outbursts for fear of what they may touch off both in ourselves and the ones we burst out at. We smolder instead. If people hurt us or cheat us or stand for things we abominate, we’re less apt to bear arms against them than to bear grudges. We stay out of their way. When we declare war, it is mostly submarine warfare, and since our attacks are beneath the surface, it may be years before we know fully the damage we have either given or sustained.

Jesus says we are to love our enemies and pray for them, meaning love not in an emotional sense but in the sense of willing their good, which is the sense in which we love ourselves. It is a tall order even so. African Americans love white supremacists? The longtime employee who is laid off just before he qualifies for retirement with a pension love the people who call him in to break the news? The mother of the molested child love the molester? But when you see as clearly as that who your enemies are, at least you see your enemies clearly too.

You see the lines in their faces and the way they walk when they’re tired. You see who their husbands and wives are, maybe. You see where they’re vulnerable. You see where they’re scared. Seeing what is hateful about them, you may catch a glimpse also of where the hatefulness comes from. Seeing the hurt they cause you, you may see also the hurt they cause themselves. You’re still light-years away from loving them, to be sure, but at least you see how they are human even as you are human, and that is at least a step in the right direction. It’s possible that you may even get to where you can pray for them a little, if only that God forgive them because you yourself can’t, but any prayer for them at all is a major breakthrough.

In the long run, it may be easier to love the ones we look in the eye and hate, the enemies, than the ones whom—because we’re as afraid of ourselves as we are of them—we choose not to look at, at all.

“Pray for them a little, if only that God forgive them because you yourself can’t . . . .”

When I read those words I was reminded of an incident in my own life which I’m pretty sure I have told here before. Back when I was a practicing attorney defending doctors and dentists in malpractice cases, I had occasion to defend a maxillofacial surgeon whose hobby was sculpting. One of the pieces he showed me was a crucifix on which the face of Jesus was contorted in extreme rage. When I asked him what that was all about, he asked if I remembered Jesus’ words in the Gospel according to Luke: “Father, forgive them; for they do not know what they are doing.” (Luke 23:34) He said he’d never heard those words as expressing forgiveness on Jesus’ part. Quite to the contrary, he said, he heard Jesus saying, “You forgive them, because right now, I can’t!”

Jesus was put in that place on that cross because he was holy – set apart for God’s particular purpose. Jesus was put in that place on that cross because he was perfect – he had a goal, a purpose, to be good, to live according to the law of love, to demonstrate God’s love for all humankind. If he was truly to live that life, to show that love, his integrity required that he do and say the things that put him in that place on that cross. But if my dentist client was correct (and I think he may have been), the best that even he could do in all his holiness, in all his perfection, in all his integrity, was turn forgiveness over to God; on his own on that cross, Jesus couldn’t do it.

And there is the answer to our question: How do we live with integrity? How can we be holy and perfect? Well, it’s what I suggested earlier, by imitating Christ, and that means by turning things over to God. On his own on that cross, Jesus couldn’t do it; on our own, we cannot do it. The Psalmist put it this way:

There is no king that can be saved by a mighty army; *

a strong man is not delivered by his great strength.

The horse is a vain hope for deliverance; *

for all its strength it cannot save. (Ps. 33:16-17; BCP version)

and again

Though my flesh and my heart should waste away, *

God is the strength of my heart and my portion for ever. (Ps. 73:26)

In our human weakness, we may be (we probably are) unable to not hate anyone, unable to eschew vengeance, unable to let go of our grudges. We may be (we probably are) unable to love our enemies or to pray for those who persecute us. But that’s OK. Because if the best we can do is pray, “God, you forgive them, because right now, I can’t!” that will be enough.

Let us pray:

O God, the Father of all, whose Son commanded us to love our enemies: Lead them and us from prejudice to truth: deliver them and us from hatred, cruelty, and revenge; and in your good time enable us all to stand reconciled before you, through Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen. (BCP 1979, page 816)

====================

A request to my readers: I’m trying to build the readership of this blog and I’d very much appreciate your help in doing so. If you find something here that is of value, please share it with others. If you are on Facebook, “like” the posts on your page so others can see them. If you are following me on Twitter, please “retweet” the notices of these meditations. If you have a blog of your own, please include mine in your links (a favor I will gladly reciprocate). Many thanks!

====================

Father Funston is the rector of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Medina, Ohio.

The words of Caiaphas the high priest are reported by John as a prophecy that Jesus’ death would be an atoning sacrifice, that he would “die for the nation, and not for the nation only, but to gather into one the dispersed children of God.” (vv. 51-52) But I read them this morning as nothing more than political calculation.

The words of Caiaphas the high priest are reported by John as a prophecy that Jesus’ death would be an atoning sacrifice, that he would “die for the nation, and not for the nation only, but to gather into one the dispersed children of God.” (vv. 51-52) But I read them this morning as nothing more than political calculation.  My favorite thing in the Book of Proverbs is the personification of Lady Wisdom. Perhaps because of the further development of her portrait in Chapter 8, where she is said to have been with God in the moments of creation, “daily his delight, rejoicing before him always, rejoicing in his inhabited world and delighting in the human race” (vv. 30-31), I see her as young, slender, and athletic, her rejoicing being manifest as dance.

My favorite thing in the Book of Proverbs is the personification of Lady Wisdom. Perhaps because of the further development of her portrait in Chapter 8, where she is said to have been with God in the moments of creation, “daily his delight, rejoicing before him always, rejoicing in his inhabited world and delighting in the human race” (vv. 30-31), I see her as young, slender, and athletic, her rejoicing being manifest as dance. How does one “test the spirits”? How does one divine the promptings of the spirit or determine the will of God? That’s always the question we must face. In the ancient tabernacle, the high priest’s vestments included a breastplate in which he kept a couple of stones called the urim and the thummim (Exodus 28:30). What those were is a subject of much speculation, but one theory is that they were sort of like dice. The belief is that the high priest cast these dice to determine God’s guidance, to “test the spirit” when faced with a difficult decision.

How does one “test the spirits”? How does one divine the promptings of the spirit or determine the will of God? That’s always the question we must face. In the ancient tabernacle, the high priest’s vestments included a breastplate in which he kept a couple of stones called the urim and the thummim (Exodus 28:30). What those were is a subject of much speculation, but one theory is that they were sort of like dice. The belief is that the high priest cast these dice to determine God’s guidance, to “test the spirit” when faced with a difficult decision. Jesus doesn’t ask much, does he? Only perfection! “Be perfect,” he tells us, “as your heavenly Father is perfect.” Of course, Jesus is simply echoing the words Moses spoke on God’s behalf delivering the Law to the Hebrews: “You shall be holy, for I the Lord your God am holy.” What can this mean? How can we be expected to be perfect and holy like God? How can we do that, especially when both Moses and Jesus insist that that means, among other things, loving our enemies, not seeking redress, not holding a grudge, and not getting that to which we are sure we are entitled?

Jesus doesn’t ask much, does he? Only perfection! “Be perfect,” he tells us, “as your heavenly Father is perfect.” Of course, Jesus is simply echoing the words Moses spoke on God’s behalf delivering the Law to the Hebrews: “You shall be holy, for I the Lord your God am holy.” What can this mean? How can we be expected to be perfect and holy like God? How can we do that, especially when both Moses and Jesus insist that that means, among other things, loving our enemies, not seeking redress, not holding a grudge, and not getting that to which we are sure we are entitled? This, for me, is the issue of our day. It is the religious issue. It is the economic issue. It is the political issue. It is the moral issue. I think the answer to John’s question is, “It doesn’t.”

This, for me, is the issue of our day. It is the religious issue. It is the economic issue. It is the political issue. It is the moral issue. I think the answer to John’s question is, “It doesn’t.”

It has been said that all human communication, even at its best, is an approximation of meaning. This is especially true of religious communication which is almost always analogic. When we try to speak of God we mean both more and less than we say; when we listen to others speak of God, we understand both more and less than we hear.

It has been said that all human communication, even at its best, is an approximation of meaning. This is especially true of religious communication which is almost always analogic. When we try to speak of God we mean both more and less than we say; when we listen to others speak of God, we understand both more and less than we hear.  “The Lord watch between me and thee. . . . ” Years ago (several more than forty) I graduated from high school at the tender age of 16 and announced to my parents that I was getting married.

“The Lord watch between me and thee. . . . ” Years ago (several more than forty) I graduated from high school at the tender age of 16 and announced to my parents that I was getting married.  There’s been a dust-up in the press recently. A lot of ink (mostly secular press ink) spilled on the question of camels in the Bible. This is because some scientific, archeological evidence has been turned up suggesting that camels have been only relatively recently domesticated in the regions of the eastern Mediterranean, nowhere near as far back as the stories of the patriarchs and matriarchs in the Books of Moses would put them. It is, says the scientific evidence, impossible that Jacob should have “set his children and his wives on camels” because there were no domesticated camels at the time, how ever far back we think that may have been.

There’s been a dust-up in the press recently. A lot of ink (mostly secular press ink) spilled on the question of camels in the Bible. This is because some scientific, archeological evidence has been turned up suggesting that camels have been only relatively recently domesticated in the regions of the eastern Mediterranean, nowhere near as far back as the stories of the patriarchs and matriarchs in the Books of Moses would put them. It is, says the scientific evidence, impossible that Jacob should have “set his children and his wives on camels” because there were no domesticated camels at the time, how ever far back we think that may have been. When I was studying for ordination, one of the more interesting thinkers I read was the French Reformed theologian Jacques Ellul. Ellul was a lawyer and a sociologist; he was heavily influenced by the work of Karl Barth and of Søren Kierkegaard. He adopted a dialectic approach to theology and argued that only such a method could lead to understanding of Scripture; we cannot understand the Biblical text, he asserted, except be seeing it as a network of contradictions, a history of crises and the resolution of the crises, a series of apparent abandonments and the hope which arises from and resolves the abandonment.

When I was studying for ordination, one of the more interesting thinkers I read was the French Reformed theologian Jacques Ellul. Ellul was a lawyer and a sociologist; he was heavily influenced by the work of Karl Barth and of Søren Kierkegaard. He adopted a dialectic approach to theology and argued that only such a method could lead to understanding of Scripture; we cannot understand the Biblical text, he asserted, except be seeing it as a network of contradictions, a history of crises and the resolution of the crises, a series of apparent abandonments and the hope which arises from and resolves the abandonment.