====================

A homily offered by the Rev. Dr. C. Eric Funston on the 23rd Sunday after Pentecost, October 23, 2016, to the people of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Medina, Ohio, where Fr. Funston is rector.

(The lessons for the day are Proper 24C of the Revised Common Lectionary: Sirach 35:12-17; Psalm 84:1-6; 2 Timothy 4:6-8,16-18; and Luke 18:9-14. These lessons can be read at The Lectionary Page.)

====================

For the past couple of weeks in the Daily Office lectionary and today in the Sunday lectionary we are reading from the Wisdom of Yeshua ben Sira, some times called Sirach, sometimes called Ecclesiasticus, one of the books of the Apocrypha, those books recognized by the Roman and Eastern Orthodox churches as canonical, but rejected by Protestants. Anglicans steer a middle course and accept them for moral teaching, but not as the basis for religious doctrine. The text is a late example of what is called “wisdom literature,” instruction in ethics and proper social behavior for young men, especially those likely to take a role in governance.

For the past couple of weeks in the Daily Office lectionary and today in the Sunday lectionary we are reading from the Wisdom of Yeshua ben Sira, some times called Sirach, sometimes called Ecclesiasticus, one of the books of the Apocrypha, those books recognized by the Roman and Eastern Orthodox churches as canonical, but rejected by Protestants. Anglicans steer a middle course and accept them for moral teaching, but not as the basis for religious doctrine. The text is a late example of what is called “wisdom literature,” instruction in ethics and proper social behavior for young men, especially those likely to take a role in governance.

Ben Sira was written early in the 2nd Century before Christ by a Jewish scribe named Shimon ben Yeshua ben Eliezer ben Sira of Jerusalem. The Jewish nation was then under domination of the Seleucid Empire, a Greek-speaking kingdom centered in modern day Syria. Society in Jerusalem was very polarized: powerful vs. weak; rich vs. poor; Jew vs. Gentile. Ben Sira sought to guide his students through socially ambivalent times.

Among the topics he addresses is the proper forms and attitudes of worship. The Seleucid governors had involved themselves in the affairs of the Temple and, therefore, many people (especially the precursors of the Pharisees) believed that Temple worship was comprised and invalid. Furthermore, for many of the city’s wealthy participation in Temple rituals was a matter of show to advance themselves and their agenda; they offered mere lip service to God while oppressing the poor and helpless.

In this social milieu, Ben Sira offered instruction on the nature of worship, sacrifice, and prayer in Chapters 34 and 35 of the book. In Chapter 34 he describes worship that is not acceptable to God:

The Most High is not pleased with the offerings of the ungodly, nor for a multitude of sacrifices does he forgive sins. Like one who kills a son before his father’s eyes is the person who offers a sacrifice from the property of the poor. The bread of the needy is the life of the poor; whoever deprives them of it is a murderer. To take away a neighbor’s living is to commit murder; to deprive an employee of wages is to shed blood. When one builds and another tears down, what do they gain but hard work? When one prays and another curses, to whose voice will the Lord listen? If one washes after touching a corpse, and touches it again, what has been gained by washing? So if one fasts for his sins, and goes again and does the same things, who will listen to his prayer? And what has he gained by humbling himself? (Ben Sira 34:23-31)

He follows this up with the advice we heard in our reading today: “Be generous when you worship the Lord, and do not stint the first fruits of your hands. With every gift show a cheerful face, and dedicate your tithe with gladness. Give to the Most High as he has given to you, and as generously as you can afford.” (Ben Sira 35:10-12)

Ben Sira’s wisdom would have been well known to the people of Jesus’ time. Portions of the book were found among the Dead Sea Scrolls, and a nearly complete scroll was discovered at Masada, the Jewish fortress destroyed by the Romans in 73 AD. In addition, there are numerous quotations of the book in the Talmud, and the Anglican scholar Henry Chadwick (1920-2008) cogently argued that Jesus even quoted or paraphrased it on several occasions, including in the petitions of the Lord’s Prayer.

In our gospel lesson today, Jesus told the parable of two men praying: a Pharisee, who worships strictly in accordance with the law of Moses but whose life may not reflect that, and a tax collector, whose life is criticized by everyone around him but whose worship is as open and sincere as it can be. Jesus’ original audience would have been very familiar with Ben Sira’s advice about worship and would have thought of it as background for the story. They would have known that Jesus was referring back to a concern about hypocritical worship, about worship that is merely for show, about worship coming from a life that does not honor the commandments, a concern dating back many years. They would have known who Jesus was condemning, just like we do! They knew that Jesus was not talking about them, just like we know that Jesus is not talking about us! Thank God that we are not like the bad people who pray with self-righteousness and contempt for others . . . .

Oh . . . wait a minute! You see what Jesus has done? He’s trapped us! He’s tricked us into judging the Pharisee, to regarding him with contempt. And by judging the Pharisee we have become like the Pharisee; in order to get Jesus’ point we have to point to the Pharisee and his sin. By pointing to someone else, to “thieves, rogues, adulterers, or even . . . this tax collector,” and to their sins, the Pharisee condemns himself; by pointing to the Pharisee and his sin, we condemn ourselves.

Clever, sneaky preacher, that Jesus! How do we become more like the tax collector and less like the Pharisee? Ben Sira instructed his students to look worship with the eyes and understanding of God, with humility and without partiality.

So here’s an exercise . . . look at the other people all around you in church today. You know most of these people; some of them are in your family; some of them are your friends; you go to breakfast with some of them every Sunday. You may not know others; some are people you see here on Sunday but don’t otherwise socialize with; some may be people you don’t know at all. But about all of them, you do know two things. First, you know that God loves them; God loves every single person in this church today. God made them; God knows them; God loves them.

The second thing you know is that nobody in this church today is perfect. The religious way to say that is that every one of us is a sinner. Each one of us says and does things that hurt others; each one of us says and does things that hurt ourselves; each one of us says and does things that hurt God. Sometimes we do that intentionally; more often we do it negligently. But the simple truth is, whatever the reason for it may be, that we do it.

And here’s a third thing you know, and this you know about yourself . . . that the two things you know about all these people around you in church are also true of you. These are the two central truths of the Christian faith: that we are sinners and that God loves us anyway.

Now I’d like to ask you all to stand, as you may be able.

Raise your right hand, palm cupped up. Receive in that hand the truth that God loves you, that God loves all of us. Now raise your left hand, palm cupped up. Offer from that hand to God the truth that you are not perfect, that you are a sinner. See how your right hand is still holding the first truth; the second doesn’t change it at all. Not about you, not about anyone!

This, by the way, is called the orans position, the ancient position of prayer, standing with one’s hands up-raised, open to God; it has a rich tradition in Jewish and Christian practice, one’s body representing the spirit open to God’s grace.

The Pharisee in the parable failed to be fully open, fully honest with God or with himself. He was willing to raise the one hand to receive God’s blessing, but was unwilling to raise the other, unwilling to admit that he was imperfect, that he was like the thieves, rogues, adulterers, and tax collectors, that he was like us.

Jesus, clever, sneaky preacher that he is, tricks us into acknowledging that we are like the Pharisee. Like Ben Sira before him, he encourages us to place ourselves fully before God, fully open to God, praying with the tax collector, “God, be merciful to me, a sinner!”

You might say that Jesus is encouraging us to live generously. And that brings us to R____ S_________ who would like to say a few words about our Living Generously Annual Fund Campaign and his personal story of stewardship.

====================

Father Funston is the rector of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Medina, Ohio.

“Whoever comes to me and does not hate father and mother, wife and children, brothers and sisters, yes, and even life itself, cannot be my disciple. * * * None of you can become my disciple if you do not give up all your possessions.”

“Whoever comes to me and does not hate father and mother, wife and children, brothers and sisters, yes, and even life itself, cannot be my disciple. * * * None of you can become my disciple if you do not give up all your possessions.” Our reading from the Book of Isaiah today is the second half of chapter 58, a chapter which begins with God ordering the prophet to “Shout out,” to “do not hold back,” to “lift up [his] voice like a trumpet” with God’s answer to a question asked by the people of Jerusalem: “Why do we fast, but you do not see? Why humble ourselves, but you do not notice?” (Isaiah 58:1,3a)

Our reading from the Book of Isaiah today is the second half of chapter 58, a chapter which begins with God ordering the prophet to “Shout out,” to “do not hold back,” to “lift up [his] voice like a trumpet” with God’s answer to a question asked by the people of Jerusalem: “Why do we fast, but you do not see? Why humble ourselves, but you do not notice?” (Isaiah 58:1,3a) In philosophy and theology there is an exercise named by the Greek word deiknumi. The word simply translated means “occurrence” or “evidence,” but in philosophy it refers to a “thought experiment,” a sort of meditation or exploration of a hypothesis about what might happen if certain facts are true or certain situations experienced. It’s particularly useful if those situations cannot be replicated in a laboratory or if the facts are in the past or future and cannot be presently experienced. St. Paul uses the word only once in his epistles: in the last verse of chapter 12 of the First Letter to the Corinthians, he uses the verbal form when he admonishes his readers to “strive for the greater gifts. And I will show you [deiknuo, ‘I will give you evidence of’] a still more excellent way.” It is the introduction to his famous treatise on agape, divine love, a thought experiment (if you will) about the best expression, the “still more excellent” expression of the greatest of the virtues.

In philosophy and theology there is an exercise named by the Greek word deiknumi. The word simply translated means “occurrence” or “evidence,” but in philosophy it refers to a “thought experiment,” a sort of meditation or exploration of a hypothesis about what might happen if certain facts are true or certain situations experienced. It’s particularly useful if those situations cannot be replicated in a laboratory or if the facts are in the past or future and cannot be presently experienced. St. Paul uses the word only once in his epistles: in the last verse of chapter 12 of the First Letter to the Corinthians, he uses the verbal form when he admonishes his readers to “strive for the greater gifts. And I will show you [deiknuo, ‘I will give you evidence of’] a still more excellent way.” It is the introduction to his famous treatise on agape, divine love, a thought experiment (if you will) about the best expression, the “still more excellent” expression of the greatest of the virtues. God’s response to Abraham’s challenge is to take Abraham outside and show him the stars and ask him, “Has it ever occurred to you that you might be wrong?” Well, God doesn’t, actually . . . but that’s what it boils down to. God’s response to Abraham is, “Thank again!”

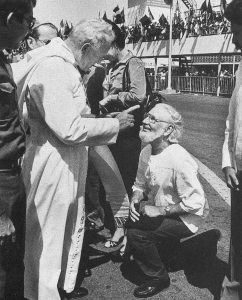

God’s response to Abraham’s challenge is to take Abraham outside and show him the stars and ask him, “Has it ever occurred to you that you might be wrong?” Well, God doesn’t, actually . . . but that’s what it boils down to. God’s response to Abraham is, “Thank again!” When Pope John Paul II scolded Fr. Cardenal upon the his arrival in Nicaragua, it was because Cardenal had collaborated with the Marxist Sandinistas and, after the Sandinista victory in 1979, he became their government’s Minister of Culture. His brother, Fr. Fernando Cardenal S.J. also worked with the Sandinista government in the Ministry of Education, directing a successful literacy campaign. There were a handful of other priests working in the government, as well.

When Pope John Paul II scolded Fr. Cardenal upon the his arrival in Nicaragua, it was because Cardenal had collaborated with the Marxist Sandinistas and, after the Sandinista victory in 1979, he became their government’s Minister of Culture. His brother, Fr. Fernando Cardenal S.J. also worked with the Sandinista government in the Ministry of Education, directing a successful literacy campaign. There were a handful of other priests working in the government, as well.  We know that if there are tribal circles on that foundational paper, they are more like the circles on a Venn diagram, not only touching but overlapping. That was true of the ancient Hebrews; their tribalism might demand ethnic purity, but they never achieved it; the Old Testament demonstrates that, again and again! Modern ideological tribalism is no different. Ideologies, religious beliefs, political opinions differ in many ways, but in many others they share much in common; they overlap. People’s lives and opinions overlap, but ideological tribalism encourages us to hear only the differing opinions and blinds us to our similar lives.

We know that if there are tribal circles on that foundational paper, they are more like the circles on a Venn diagram, not only touching but overlapping. That was true of the ancient Hebrews; their tribalism might demand ethnic purity, but they never achieved it; the Old Testament demonstrates that, again and again! Modern ideological tribalism is no different. Ideologies, religious beliefs, political opinions differ in many ways, but in many others they share much in common; they overlap. People’s lives and opinions overlap, but ideological tribalism encourages us to hear only the differing opinions and blinds us to our similar lives. Last Monday, we celebrated our country’s 240th birthday in a way that is quite different from other celebrations of what we might call “national identity days” around the world.

Last Monday, we celebrated our country’s 240th birthday in a way that is quite different from other celebrations of what we might call “national identity days” around the world.  As many of you know, this past week was a harrowing one for my wife and for me; specifically, Wednesday was one of those days you would rather not have to live through. In the afternoon, I was told by a urologist that I probably have prostate cancer, and later that night Evelyn nearly died from pulmonary embolism. She is OK now – I will be leaving right after this service to bring her home from the hospital – and my diagnosis will be either confirmed or proven wrong by a biopsy in about a month.

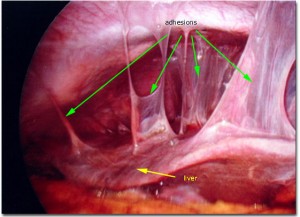

As many of you know, this past week was a harrowing one for my wife and for me; specifically, Wednesday was one of those days you would rather not have to live through. In the afternoon, I was told by a urologist that I probably have prostate cancer, and later that night Evelyn nearly died from pulmonary embolism. She is OK now – I will be leaving right after this service to bring her home from the hospital – and my diagnosis will be either confirmed or proven wrong by a biopsy in about a month.  As a human body moves, its tissues or organs normally move and shift, repositioning themselves in relation to one another within a normative range; nothing in the body is static. These tissues and organs have slippery surfaces and natural lubricants to allow this. Inflammation, infection, surgery, or injury can cause bands of scar-like tissue to form between the surfaces of these organs and tissues, causing them to stick together and prevent this natural movement.

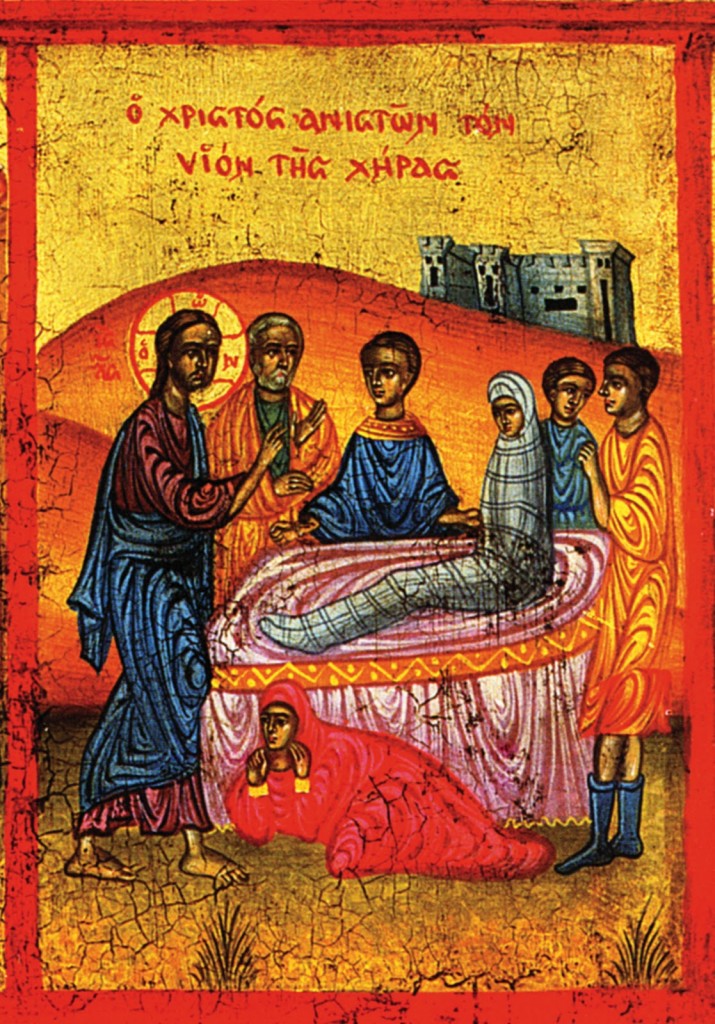

As a human body moves, its tissues or organs normally move and shift, repositioning themselves in relation to one another within a normative range; nothing in the body is static. These tissues and organs have slippery surfaces and natural lubricants to allow this. Inflammation, infection, surgery, or injury can cause bands of scar-like tissue to form between the surfaces of these organs and tissues, causing them to stick together and prevent this natural movement.  I am convinced that there is no grief quite so profound as that of a mother whose child has died. I know that fathers in the same situation feel a nearly as intense sorrow at the death of their sons or daughters, but having spent time with grieving parents, I am convinced that the grief of a mother faced with the loss of her child is the deepest sadness in human experience.

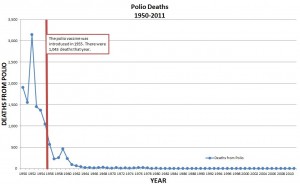

I am convinced that there is no grief quite so profound as that of a mother whose child has died. I know that fathers in the same situation feel a nearly as intense sorrow at the death of their sons or daughters, but having spent time with grieving parents, I am convinced that the grief of a mother faced with the loss of her child is the deepest sadness in human experience. The year that I was born was the worst of the mid-20th Century polio epidemic; about 55,000 Americans contracted the disease that year and more than 3,100 died, mostly children. As a society, we decided that that much illness and death was simply unacceptable, and an all-out effort was underway to put an end to it. Within just a few years, Jonas Salk and his team developed the vaccine which ended the epidemic; a few years later, the Sabin oral vaccine was developed and polio has been just about eradicated throughout the world. (Graphic from

The year that I was born was the worst of the mid-20th Century polio epidemic; about 55,000 Americans contracted the disease that year and more than 3,100 died, mostly children. As a society, we decided that that much illness and death was simply unacceptable, and an all-out effort was underway to put an end to it. Within just a few years, Jonas Salk and his team developed the vaccine which ended the epidemic; a few years later, the Sabin oral vaccine was developed and polio has been just about eradicated throughout the world. (Graphic from  On January 21, 2013, Hadiya Pendleton, a 15-year-old high school student from the south side of Chicago, marched with her school’s band in President Obama’s second inaugural parade. One week later, Hadiya was shot and killed. She was shot in the back while standing with friends inside Harsh Park in Kenwood, Chicago, after taking her final exams. She was not the intended victim; the perpetrator, a gang member, had mistaken her group of friends for a rival gang.

On January 21, 2013, Hadiya Pendleton, a 15-year-old high school student from the south side of Chicago, marched with her school’s band in President Obama’s second inaugural parade. One week later, Hadiya was shot and killed. She was shot in the back while standing with friends inside Harsh Park in Kenwood, Chicago, after taking her final exams. She was not the intended victim; the perpetrator, a gang member, had mistaken her group of friends for a rival gang.  John the Baptizer came, Luke tells us, “proclaiming a baptism of repentance for the forgiveness of sins.” (Lk. 3:3) In today’s Gospel lesson, John tells the crowds who came to him, “Bear fruits worthy of repentance.” (v. 8) Our catechism teaches us that repentance is required of us to receive the Sacraments. With regard to baptism, the catechetical requirement is that we “renounce Satan, repent of our sins, and accept Jesus as our Lord and Savior;” with regard to the Holy Eucharist, that we “examine our lives, repent of our sins, and be in love and charity with all people.” (BCP 858, 860) But John’s admonition and the Catechism’s requirements leave us wondering, “What exactly is ‘repentance’?”

John the Baptizer came, Luke tells us, “proclaiming a baptism of repentance for the forgiveness of sins.” (Lk. 3:3) In today’s Gospel lesson, John tells the crowds who came to him, “Bear fruits worthy of repentance.” (v. 8) Our catechism teaches us that repentance is required of us to receive the Sacraments. With regard to baptism, the catechetical requirement is that we “renounce Satan, repent of our sins, and accept Jesus as our Lord and Savior;” with regard to the Holy Eucharist, that we “examine our lives, repent of our sins, and be in love and charity with all people.” (BCP 858, 860) But John’s admonition and the Catechism’s requirements leave us wondering, “What exactly is ‘repentance’?”