====================

This sermon was preached on Sunday, August 26, 2012, at St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Medina, Ohio, where Fr. Funston is rector.

(Revised Common Lectionary, Proper 16B: 1 Kings 8:1,6,10-11,22-30,41-43; Psalm 84; Ephesians 6:10-20; and John 6:56-69.)

====================

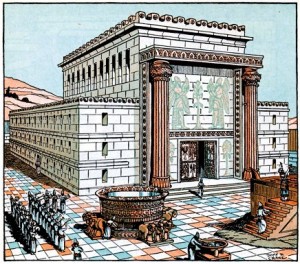

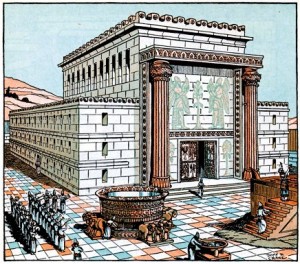

On the cover of our worship bulletin this morning is a depiction of King Solomon’s Temple. It’s an artist’s rendering of someone’s reconstruction of the Temple based on the description of its construction in the Old Testament record. Our first reading today (from the First Book of Kings), as long as it was, is just a small part of the dedicatory prayer that King Solomon offers when the Temple is finished and consecrated.

On the cover of our worship bulletin this morning is a depiction of King Solomon’s Temple. It’s an artist’s rendering of someone’s reconstruction of the Temple based on the description of its construction in the Old Testament record. Our first reading today (from the First Book of Kings), as long as it was, is just a small part of the dedicatory prayer that King Solomon offers when the Temple is finished and consecrated.

The building of the Temple marked a very significant change in the Jewish religion. Well, really, let’s not call it the Jewish religion because it wasn’t that, yet. Let’s just say, “The religion of the people of Israel.” These people were not, though we often imagine them to be, strict monotheists. Even in this prayer Solomon leaves open the question of whether there might be gods other than their God: “O Lord, God of Israel, there is no God like you in heaven above or on earth beneath.” There might be other gods, lesser gods perhaps, demigods, or even demons, part of a heavenly pantheon of gods, but this God, the God of the People of Israel is greater than any of those others.

At this time, all the different nations, sometimes even different clans or families, had their own religions, their own gods. And nearly all of these religions believed the gods to be sort of tied to the land. If you moved from one place to another, you stopped worshiping the god of the first place and took up the worship of the god of your new residence. If a woman married outside of her family or tribe, married into a different clan, she would give up the religion of her family and take up that of her husband.

The People of Israel’s God, however, was different. Their God was not tied to a particular place. Their God was connected to a holy object, instead. God was associated with the Ark of the Covenant which they had created in the desert to contain God’s holy relics, the tablets of the Law given to Moses at Sinai (together with a pot of manna and Aaron’s staff). They carried the Ark with them, actually before them, as they traveled through the desert, as they crossed into the Holy Land, as they conquered the Canaanites and took possession of the country.

You may recall that in those first years, the People of Israel had no monarch: they considered God to be their king. The histories are silent as to where the Ark was kept during the period of the Judges, or during the reign of the first monarch, King Saul. But we know that David wanted to build a permanent location for it; he wanted to build a Temple. But God refused. He told David, through the prophet Nathan,

Are you the one to build me a house to live in? I have not lived in a house since the day I brought up the people of Israel from Egypt to this day, but I have been moving about in a tent and a tabernacle. (2 Sam. 7:5-6)

So David did not build the Temple, but he did build a special tent in his city, Bethlehem, and brought the Ark there. We are told

David danced before the Lord with all his might; David was girded with a linen ephod. So David and all the house of Israel brought up the ark of the Lord with shouting, and with the sound of the trumpet. . . . They brought in the ark of the Lord, and set it in its place, inside the tent that David had pitched for it. (2 Sam. 6:15, 17)

David designed the Temple, but he never built it. His son Solomon was the one to do that.

So the Temple was finished, the sacred implements from David’s tent had been moved into it, the Ark of the Covenant was installed into the Holy of Holies where only the High Priest would be allowed to go and Solomon offers this long prayer of dedication. In it he asks a very important question: “But will God indeed dwell on the earth?” (1 Kings 8:27) By building the Temple, Solomon sought to provide God a place to dwell on earth and, in so doing, he made the religion of his people more like that of their neighbors than it had been.

Remember their religions had tied their gods to particular places whereas the God of Israel had moved about the countryside with his People. Now God had a permanent home and, over time, the Jews would centralize God’s worship in the Temple and they would eventually decree, in the Book of Deuteronomy, that the cultic part of their faith could only be performed in that place. Sure, people could gather anywhere for prayer, they could go synagogues for religious instruction, but they could only offer sacrifice and perform the Temple rites in the Temple at Jerusalem. God had become tied to a place. (This was one of the differences the Jews had with Samaritans with whom they shared a devotion to God and who also followed the Law as set out in Genesis, Exodus, Numbers, and Leviticus, but who rejected the restrictions of Deuteronomy and had their own temples, primarily at Mt. Gerazim.)

By the time of Jesus, Solomon’s question had been firmly answered by the Jews. Yes, said their religion, God will dwell on earth, in this place, this Temple in Jerusalem. In the birth of Jesus, however, God gave a different answer: God will not dwell in a building in a particular place; God will dwell with and among God’s People: as the Gospel of John affirms, “The Word became flesh and lived among us.” (John 1:14) Will God indeed dwell on earth? Yes, God will live among God’s people as one of us. God lived among us as an infant born in Bethlehem. God lived among us as an itinerant rabbi who had no home. God lived among us as a rabbi accused of being a rabble-rouser. God lived among us as a rabble-rouser condemned to die a criminal’s death. God lived among us as a criminal executed on a cross.

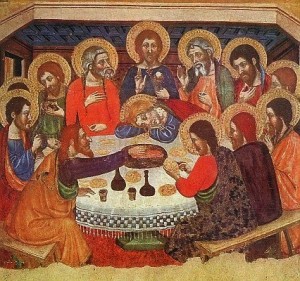

On the night before he died, he gathered with his friends for a Passover meal. There is some debate as to whether it was a Seder, the sacred meal of Judaism, but if it was he radically changed its nature, just as Solomon building the Temple had radically changed the nature of the religion of Israel. In the Passover meal, Jews become one with their ancestors; the Passover story is brought present to them in the ritual of the Seder and they, in turn, live through the Passover story, but the meal does not bring God into their midst. When Jesus took the bread of affliction and said, “This is my body,” when he took the cup of blessing and said, “This is my blood,” when he told his followers, “Do this when you remember me,” when he promised, “Where two or three gather, I am there,” Jesus gave us a power and an obligation unlike any given before to any people by God. We have the privilege to bring God present among us in the Bread and Wine of the Eucharist, the Christ’s Body and Blood.

Where were you on July 20, 1969? In July of 1969 I was living in a boarding house and studying in Florence, Italy. The boarding house or pensione in which I lived, Pensione Frati, did not have a television. My landlord, Colonello Roberto Frati, arranged for me and the other Americans living there to go to his sister-in-law’s home where we could watch Neil Armstrong’s and Buzz Aldrin’s moon landing on her TV – this great big box of a television set with a tiny black-and-white screen. We all gathered around that box peering into that tiny screen listening to the Italian news commentators and struggling to hear the American commentary behind them. I’m sure that when we heard of Commander Armstrong’s death we all thought about wherever we were on that day at that moment when he stepped out of the lunar lander and became the first human being to walk on another world.

Where were you on July 20, 1969? In July of 1969 I was living in a boarding house and studying in Florence, Italy. The boarding house or pensione in which I lived, Pensione Frati, did not have a television. My landlord, Colonello Roberto Frati, arranged for me and the other Americans living there to go to his sister-in-law’s home where we could watch Neil Armstrong’s and Buzz Aldrin’s moon landing on her TV – this great big box of a television set with a tiny black-and-white screen. We all gathered around that box peering into that tiny screen listening to the Italian news commentators and struggling to hear the American commentary behind them. I’m sure that when we heard of Commander Armstrong’s death we all thought about wherever we were on that day at that moment when he stepped out of the lunar lander and became the first human being to walk on another world.

What almost nobody knew until a long time afterward was that something else happened on the moon that day. Buzz Aldrin, a devout Christian and an ordained elder in his Presbyterian congregation, had taken a communion kit with some bread and wine to the moon. In the Presbyterian Church, the lay elders of the church who serve a function similar to our vestry members, are actually ordained by their congregation, and that ordination empowers them to bless the elements of Holy Communion. At the time Aldrin and Armstrong landed on the moon, the pastor and members of his Presbyterian church were watching TV but unlike most of us, they were also celebrating communion. Armstrong joined them across space, blessing the bread and wine on the moon and partaking there of Holy Communion.

In the act of Holy Communion we are joined with Christians everywhere and everywhen — with all those in every place who also take part in the Eucharistic feast, with all those who have done so at ever Eucharist since Christ’s last supper with his disciples, with all those who will celebration Communion in the future. We are joined with them and we are joined with God in Christ as we eat of his Body and drink of his Blood, no matter where we are on earth or even on the moon.

Will God indeed dwell on the earth? Yes! Will God dwell on the moon? Yes! God dwells with God’s People wherever the memory of Jesus is invoked in the Holy Communion, wherever bread and wine are blessed and consecrated the Body and Blood of God incarnate in Christ. God will dwell with God’s People across time and across space, even on the moon, and wherever else in this Solar System or beyond we may go, so long as we do this in memory of Jesus. Amen.

The picture of Jesus getting advice from his brothers just tickles me. John makes such a deal of it (while pointing out that his brothers did not believe in him – as the Messiah, I suppose – at the time). It seems so at odds with John’s otherwise oh-so-perfect, oh-so-divine Jesus!

The picture of Jesus getting advice from his brothers just tickles me. John makes such a deal of it (while pointing out that his brothers did not believe in him – as the Messiah, I suppose – at the time). It seems so at odds with John’s otherwise oh-so-perfect, oh-so-divine Jesus!

The Jews, John tells us, disputed among themselves as Jesus was delivering the lengthy dissertation on bread from which these statements come. Earlier he had introduced this idea that his flesh was bread to be eaten by his followers: “I am the living bread that came down from heaven. Whoever eats of this bread will live for ever; and the bread that I will give for the life of the world is my flesh.” (v. 51) The very idea of consuming human flesh is off-putting, even disgusting, and would have been extremely objectionable to the Jews; no wonder they grumbled and mumbled, complained and disputed. Even as a metaphor, the statement demands a lot from Jesus’ followers!

The Jews, John tells us, disputed among themselves as Jesus was delivering the lengthy dissertation on bread from which these statements come. Earlier he had introduced this idea that his flesh was bread to be eaten by his followers: “I am the living bread that came down from heaven. Whoever eats of this bread will live for ever; and the bread that I will give for the life of the world is my flesh.” (v. 51) The very idea of consuming human flesh is off-putting, even disgusting, and would have been extremely objectionable to the Jews; no wonder they grumbled and mumbled, complained and disputed. Even as a metaphor, the statement demands a lot from Jesus’ followers! On the cover of our worship bulletin this morning is a depiction of King Solomon’s Temple. It’s an artist’s rendering of someone’s reconstruction of the Temple based on the description of its construction in the Old Testament record. Our first reading today (from the First Book of Kings), as long as it was, is just a small part of the dedicatory prayer that King Solomon offers when the Temple is finished and consecrated.

On the cover of our worship bulletin this morning is a depiction of King Solomon’s Temple. It’s an artist’s rendering of someone’s reconstruction of the Temple based on the description of its construction in the Old Testament record. Our first reading today (from the First Book of Kings), as long as it was, is just a small part of the dedicatory prayer that King Solomon offers when the Temple is finished and consecrated. Where were you on July 20, 1969? In July of 1969 I was living in a boarding house and studying in Florence, Italy. The boarding house or pensione in which I lived, Pensione Frati, did not have a television. My landlord, Colonello Roberto Frati, arranged for me and the other Americans living there to go to his sister-in-law’s home where we could watch Neil Armstrong’s and Buzz Aldrin’s moon landing on her TV – this great big box of a television set with a tiny black-and-white screen. We all gathered around that box peering into that tiny screen listening to the Italian news commentators and struggling to hear the American commentary behind them. I’m sure that when we heard of Commander Armstrong’s death we all thought about wherever we were on that day at that moment when he stepped out of the lunar lander and became the first human being to walk on another world.

Where were you on July 20, 1969? In July of 1969 I was living in a boarding house and studying in Florence, Italy. The boarding house or pensione in which I lived, Pensione Frati, did not have a television. My landlord, Colonello Roberto Frati, arranged for me and the other Americans living there to go to his sister-in-law’s home where we could watch Neil Armstrong’s and Buzz Aldrin’s moon landing on her TV – this great big box of a television set with a tiny black-and-white screen. We all gathered around that box peering into that tiny screen listening to the Italian news commentators and struggling to hear the American commentary behind them. I’m sure that when we heard of Commander Armstrong’s death we all thought about wherever we were on that day at that moment when he stepped out of the lunar lander and became the first human being to walk on another world. Wow! Does this look familiar? The second chapter of Job begins with a scene nearly identical to that which we considered yesterday. Satan (with other heavenly beings) presents himself in the heavenly throne room and, once again, God and Satan have a conversation about Job and, once again, the bet is made. In fact, it’s sort of “double down” time! Yesterday, I argued that although the Book of Job is fiction it (like the other forms of literature found in Holy Scripture) embodies truth.

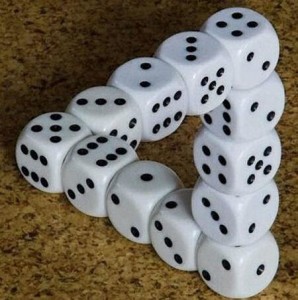

Wow! Does this look familiar? The second chapter of Job begins with a scene nearly identical to that which we considered yesterday. Satan (with other heavenly beings) presents himself in the heavenly throne room and, once again, God and Satan have a conversation about Job and, once again, the bet is made. In fact, it’s sort of “double down” time! Yesterday, I argued that although the Book of Job is fiction it (like the other forms of literature found in Holy Scripture) embodies truth. A later selection from the Book of Job was called up by the Sunday Eucharistic Lectionary several weeks ago. In my sermon I said to the congregation that the Book of Job is fiction (which it is). You should have seen the look on one of my parishioners’ face! There’s a fellow in the congregation who is, shall we say, conservative with regard to the Bible. While I don’t believe he actually considers the Bible to be the inerrant word of God per se, he’s pretty sure that it is to be taken with the highest degree of certainty and words like “myth” or “fiction” applied to Scripture are not to his liking. I swear I thought he might have an apoplectic fit right there in his pew! But let’s be honest: do we really think that God and Satan are engaged (or have ever been engaged) in a game of chance involving the lives of human beings?

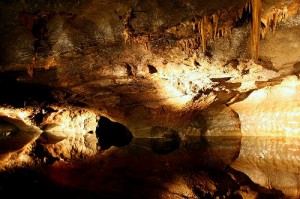

A later selection from the Book of Job was called up by the Sunday Eucharistic Lectionary several weeks ago. In my sermon I said to the congregation that the Book of Job is fiction (which it is). You should have seen the look on one of my parishioners’ face! There’s a fellow in the congregation who is, shall we say, conservative with regard to the Bible. While I don’t believe he actually considers the Bible to be the inerrant word of God per se, he’s pretty sure that it is to be taken with the highest degree of certainty and words like “myth” or “fiction” applied to Scripture are not to his liking. I swear I thought he might have an apoplectic fit right there in his pew! But let’s be honest: do we really think that God and Satan are engaged (or have ever been engaged) in a game of chance involving the lives of human beings? Psalm 130 is one of the seven “pentitential psalms” of the church (Psalms 6, 32, 38, 51, 102, 130, and 143), a tradition that stretches back to the Sixth Century if not earlier. It is also one of the “songs of ascents” (Psalms 120-134) that are believed to have been sung by pilgrims making their way up to Jerusalem or possibly when climbing up the Temple Mount for festival celebrations. Somehow it strikes me as both odd and poignant that a song or poem beginning “Out of the depths” is called a song of “ascent” – from the deepest sloughs of despond the poet calls out the Highest. Ascent, indeed!

Psalm 130 is one of the seven “pentitential psalms” of the church (Psalms 6, 32, 38, 51, 102, 130, and 143), a tradition that stretches back to the Sixth Century if not earlier. It is also one of the “songs of ascents” (Psalms 120-134) that are believed to have been sung by pilgrims making their way up to Jerusalem or possibly when climbing up the Temple Mount for festival celebrations. Somehow it strikes me as both odd and poignant that a song or poem beginning “Out of the depths” is called a song of “ascent” – from the deepest sloughs of despond the poet calls out the Highest. Ascent, indeed! I think this may be my favorite psalm. It is the psalm appointed for use on the feast of St. Francis of Assisi. It is one of the psalms approved in The Book of Common Prayer for use at a funeral; it was selected by my mother to be used at her funeral.

I think this may be my favorite psalm. It is the psalm appointed for use on the feast of St. Francis of Assisi. It is one of the psalms approved in The Book of Common Prayer for use at a funeral; it was selected by my mother to be used at her funeral.  Saint Stephen, one of the first deacons of the church, has just preached a sermon in which he has reminded his hearers, Jewish authorities in Jerusalem, that the Jews had a history of mistreatment of prophets, Their ancestors, he has said, “killed those who foretold the coming of the Righteous One, and now [his listeners] have become his betrayers and murderers.” No wonder they were angry with him.

Saint Stephen, one of the first deacons of the church, has just preached a sermon in which he has reminded his hearers, Jewish authorities in Jerusalem, that the Jews had a history of mistreatment of prophets, Their ancestors, he has said, “killed those who foretold the coming of the Righteous One, and now [his listeners] have become his betrayers and murderers.” No wonder they were angry with him.