At the end of our gospel lesson this morning, Jesus said to the crowd, “It is my Father who gives you the true bread from heaven. For the bread of God is that which comes down from heaven and gives life to the world.” They said to him, “Sir, give us this bread always.” Jesus answered, “I am the bread of life. Whoever comes to me will never be hungry, and whoever believes in me will never be thirsty.”[1] This is the beginning of Jesus’ long discourse on bread which takes up nearly the whole of Chapter 6 of the Gospel according to John and of which we will hear parts for all of the month of August.

At the end of our gospel lesson this morning, Jesus said to the crowd, “It is my Father who gives you the true bread from heaven. For the bread of God is that which comes down from heaven and gives life to the world.” They said to him, “Sir, give us this bread always.” Jesus answered, “I am the bread of life. Whoever comes to me will never be hungry, and whoever believes in me will never be thirsty.”[1] This is the beginning of Jesus’ long discourse on bread which takes up nearly the whole of Chapter 6 of the Gospel according to John and of which we will hear parts for all of the month of August.

A few verses further on, Jesus will say again, “I am the living bread that came down from heaven.” And he will add, “Whoever eats of this bread will live for ever; and the bread that I will give for the life of the world is my flesh. . . . Those who eat my flesh and drink my blood have eternal life, and I will raise them up on the last day; for my flesh is true food and my blood is true drink. Those who eat my flesh and drink my blood abide in me, and I in them.”[2]

The Jews, John tells us, disputed among themselves as Jesus was delivering this lengthy dissertation on bread. I think we can understand why! The very idea of consuming human flesh is off-putting, even disgusting, and would have been extremely objectionable to the Jews; no wonder they grumbled and mumbled, complained and disputed. Even as a metaphor, the statement demands a lot from Jesus’ followers!

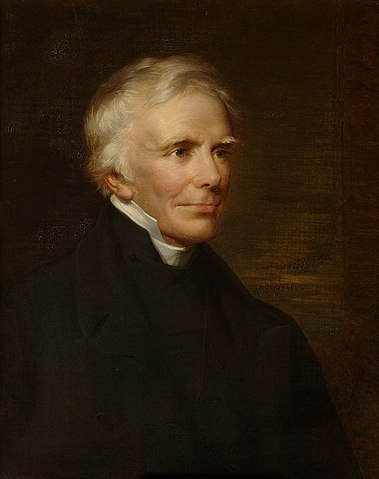

Yesterday, July 14, was the 185th anniversary of the preaching a sermon which is said to have been the beginning of the Catholic revival in the Church of England. The sermon was preached at St. Mary’s Church Oxford by the Rev. John Keble, Provost of Oriel College and Professor of Poetry at Oxford. The sermon marked the opening of the Assize Court, the summer term of the English High Court of Justice. The Assize sermon normally would have addressed matters of law and religion, but in the summer of 1833 the Parliament of the United Kingdom was debating whether to abolish (or in the language of the time “suppress”) some dioceses of the Anglican Church of Ireland which, at the time, was united with the Church of England. It was an entirely financial issue in the eyes of Parliament, but Keble and several of his friends believed this to be an encroachment of the secular establishment upon the religious and an altogether wrong thing, and so it was this portending legislation that Keble addressed in his homily, which he titled National Apostasy. He began with these words:

Yesterday, July 14, was the 185th anniversary of the preaching a sermon which is said to have been the beginning of the Catholic revival in the Church of England. The sermon was preached at St. Mary’s Church Oxford by the Rev. John Keble, Provost of Oriel College and Professor of Poetry at Oxford. The sermon marked the opening of the Assize Court, the summer term of the English High Court of Justice. The Assize sermon normally would have addressed matters of law and religion, but in the summer of 1833 the Parliament of the United Kingdom was debating whether to abolish (or in the language of the time “suppress”) some dioceses of the Anglican Church of Ireland which, at the time, was united with the Church of England. It was an entirely financial issue in the eyes of Parliament, but Keble and several of his friends believed this to be an encroachment of the secular establishment upon the religious and an altogether wrong thing, and so it was this portending legislation that Keble addressed in his homily, which he titled National Apostasy. He began with these words: In 2011 a young man in New York City named Gabriel went to a party. While there, he drank some of the alcoholic punch being served. Unknown to the young man, the punch had been spiked with a drug called Gamma-Hydroxybutyric Acid, commonly called GHB. Prescribed as Xyrem and also called by a variety of “street names,” it is known as a “date rape” or rave drug. It comes as a liquid or as a white powder that is dissolved in water, juice, or alcohol. In most people it produces euphoria, drowsiness, decreased anxiety, excited behavior, and occasionally hallucinations. For Gabriel, however, who suffered from medication-controlled epilepsy, it caused a seizure. Apparently interacting with his regularly prescribed medication, the GHB he had unknowingly consumed caused a fatal convulsion.

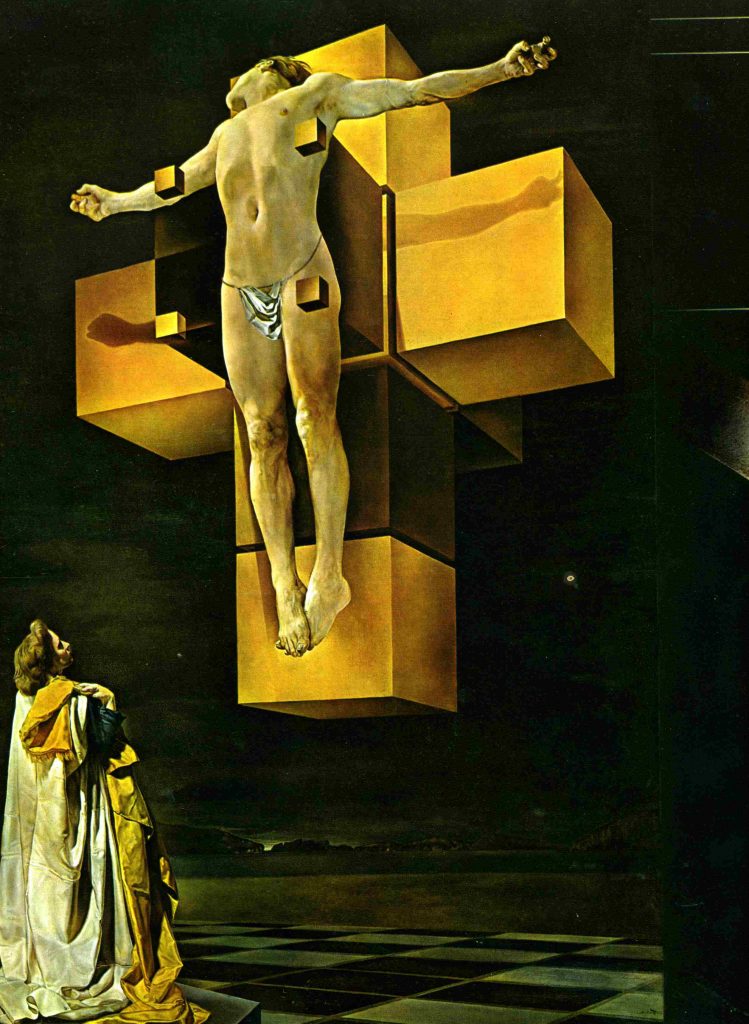

In 2011 a young man in New York City named Gabriel went to a party. While there, he drank some of the alcoholic punch being served. Unknown to the young man, the punch had been spiked with a drug called Gamma-Hydroxybutyric Acid, commonly called GHB. Prescribed as Xyrem and also called by a variety of “street names,” it is known as a “date rape” or rave drug. It comes as a liquid or as a white powder that is dissolved in water, juice, or alcohol. In most people it produces euphoria, drowsiness, decreased anxiety, excited behavior, and occasionally hallucinations. For Gabriel, however, who suffered from medication-controlled epilepsy, it caused a seizure. Apparently interacting with his regularly prescribed medication, the GHB he had unknowingly consumed caused a fatal convulsion. Sometimes I find myself at a loss for words. It doesn’t happen often, but once in a while I simply don’t know what to say about a person or an event or a spiritual feeling. On Good Friday, is one of the times when this happens. I don’t know what I want to say about Jesus or his crucifixion or the salvation we enjoy because of his death and resurrection.

Sometimes I find myself at a loss for words. It doesn’t happen often, but once in a while I simply don’t know what to say about a person or an event or a spiritual feeling. On Good Friday, is one of the times when this happens. I don’t know what I want to say about Jesus or his crucifixion or the salvation we enjoy because of his death and resurrection.  A couple of months ago, I was part of a conversation among several parishioners about the set-up for our celebrations of the Nativity. We looking at our plans for Christmas services, and a member of our altar guild exclaimed, “That’s the problem! Things are always changing around here!”

A couple of months ago, I was part of a conversation among several parishioners about the set-up for our celebrations of the Nativity. We looking at our plans for Christmas services, and a member of our altar guild exclaimed, “That’s the problem! Things are always changing around here!” Why do we do this? Why do we gather when a loved one dies and hold assemblies like this? Most human beings believe that death is not the end of the person who has passed away. Except for the few human beings who really strongly subscribe to an atheist philosophy, and they truly are a minority of our race, everyone on earth belongs to some faith group which teaches that we continue on, whether it is by reincarnation or in the Elysian Fields or the happy hunting grounds, as a guiding ancestral spirit or at rest in the presence of our Lord. So why do we do this?

Why do we do this? Why do we gather when a loved one dies and hold assemblies like this? Most human beings believe that death is not the end of the person who has passed away. Except for the few human beings who really strongly subscribe to an atheist philosophy, and they truly are a minority of our race, everyone on earth belongs to some faith group which teaches that we continue on, whether it is by reincarnation or in the Elysian Fields or the happy hunting grounds, as a guiding ancestral spirit or at rest in the presence of our Lord. So why do we do this? “In the beginning was the Word . . . .” The Prologue of John’s Gospel echoes the opening words of the Bibe, “In the beginning God said . . . .” Our God is a god who communicates, who speaks, whose Word creates.

“In the beginning was the Word . . . .” The Prologue of John’s Gospel echoes the opening words of the Bibe, “In the beginning God said . . . .” Our God is a god who communicates, who speaks, whose Word creates.