From the Letter to the Ephesians:

In Christ we have also obtained an inheritance, having been destined according to the purpose of him who accomplishes all things according to his counsel and will, so that we, who were the first to set our hope on Christ, might live for the praise of his glory. In him you also, when you had heard the word of truth, the gospel of your salvation, and had believed in him, were marked with the seal of the promised Holy Spirit; this is the pledge of our inheritance towards redemption as God’s own people, to the praise of his glory.

(From the Daily Office Lectionary – Ephesians 1:11-14 (NRSV) – January 14, 2013.)

At the emergence Christianity conversation I took part in at St. Mary’s Cathedral in Memphis, Tennessee, this past weekend a distinction was made between “emergence Christianity” and “inherited Christianity”. Paul’s thesis that “in Christ we have obtained an inheritance” and that this inheritance is “redemption as God’s own people” has brought this to mind. (For the details of this movement and some of its history, the book to read is Emergence Christianity by Phyllis Tickle, who was the keynoter of this weekend’s conversation.)

At the emergence Christianity conversation I took part in at St. Mary’s Cathedral in Memphis, Tennessee, this past weekend a distinction was made between “emergence Christianity” and “inherited Christianity”. Paul’s thesis that “in Christ we have obtained an inheritance” and that this inheritance is “redemption as God’s own people” has brought this to mind. (For the details of this movement and some of its history, the book to read is Emergence Christianity by Phyllis Tickle, who was the keynoter of this weekend’s conversation.)

The conclusion I have drawn from the Memphis Conversation is that “emergent” and “emerging” are essentially meaningless labels, other than that the former is a brand name for the Emergent Village and the latter might describe anything that can be associated with what contemporary historians are calling “The Great Emergence” (a way to describe the current upheaval in western society). If it’s an edgy praxis that somehow claims to be “Christian” and uses glitzy up-to-date technology, it can call itself “emergent” or “emerging” without regard to theological content. (Nadia Bolz-Weber referred to this when suggesting that a label that could be applied to her and to Mark Driscoll is a meaningless term.) There are so many things that claim to be “emergent” or “emerging” (from post-evangelical neo-pentacostalism to a post-theist deconstructed church that claims to be “Christian” without any of the marks of the church) that there really is no substance in these terms; they signify nothing.

Perhaps helpfully another participant has suggested that “Emergence does not modify Christianity. Emergence describes an era; Christianity describes a movement. Whether or not Christianity as we/I know it is modified in this new era remains to be seen.” That may be as far as we can currently go with defining this thing that is happening.

As for the “inherited church” and Paul’s reference to our heritage (with the Ephesians) as followers of Christ, I am struck again by the wisdom of my own Episcopal/Anglican tradition. In the 1880s the bishops of the Episcopal Church looked at the question of organic reunions of the various streams of post-Reformation Christianity and suggested there are really only four things on which Christians would need to be agree. The fourth was “the historic episcopate” which, being bishops, you can sort of understand them thinking important. I value to apostolic office of bishop, but I’m not sure it’s a necessity. The other three, though, really our what we, the “inherited church” offer as foundation for the experimentation in the faith that the “emergent” group is undertaking. What those bishops produced was called a “quadrilateral” and their four points were later affirmed by the gathered bishops of the Anglican Communion and is now referred to as The Chicago/Lambeth Quadrilateral. The substantive content of what the American bishops wrote is:

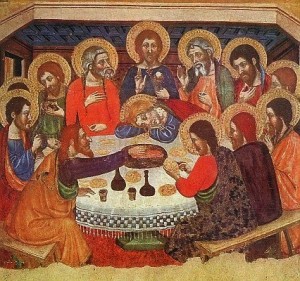

We do hereby affirm that the Christian unity . . .can be restored only by the return of all Christian communions to the principles of unity exemplified by the undivided Catholic Church during the first ages of its existence; which principles we believe to be the substantial deposit of Christian Faith and Order committed by Christ and his Apostles to the Church unto the end of the world, and therefore incapable of compromise or surrender by those who have been ordained to be its stewards and trustees for the common and equal benefit of all men.

As inherent parts of this sacred deposit, and therefore as essential to the restoration of unity among the divided branches of Christendom, we account the following, to wit:

1. The Holy Scriptures of the Old and New Testaments as the revealed Word of God.

2. The Nicene Creed as the sufficient statement of the Christian Faith.

3. The two Sacraments, — Baptism and the Supper of the Lord, — ministered with unfailing use of Christ’s words of institution and of the elements ordained by Him.

4. The Historic Episcopate, locally adapted in the methods of its administration to the varying needs of the nations and peoples called of God into the unity of His Church. (The Book of Common Prayer – 1979, page 877)

I am quite certain that some among the “emergent” or “emerging” church movement would reject this foundational deposit. I am also quite certain that without at least the first three (as I said, I’m not so certain about the necessity of bishops) the movement cannot be considered “Christian” nor would its embodiment be “church”. I think we can talk about these things critically (for instance, noting that the first does not require a belief in the literal factuality or inerrancy of Scripture, or that the third does not set out a specific theology of the Sacraments, but that both leave open the possibility of a wide variety of understandings). But I do not believe that we can abandon them.

I do not believe that “emerging” means “leaving behind.” It does not mean abandoning our inheritance.

====================

A request to my readers: I’m trying to build the readership of this blog and I’d very much appreciate your help in doing so. If you find something here that is of value, please share it with others. If you are on Facebook, “like” the posts on your page so others can see them. If you are following me on Twitter, please “retweet” the notices of these meditations. If you have a blog of your own, please include mine in your links (a favor I will gladly reciprocate). Many thanks!

====================

Father Funston is the rector of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Medina, Ohio.

Well! Here we are . . . just a few days ago I mentioned this text in regard to another lectionary reading. I am attending a conference on “emerging Christianity” this week and this text (having come up in that meditation) has been on my mind. There are many among the participants in this conversation who are quite passionate about the “emerging church” movement; they are definitely not “lukewarm”.

Well! Here we are . . . just a few days ago I mentioned this text in regard to another lectionary reading. I am attending a conference on “emerging Christianity” this week and this text (having come up in that meditation) has been on my mind. There are many among the participants in this conversation who are quite passionate about the “emerging church” movement; they are definitely not “lukewarm”. Did you pay attention to the words of the song we just sang as our sequence hymn? Listen to them again:

Did you pay attention to the words of the song we just sang as our sequence hymn? Listen to them again: I have to admit that I’m not sure how to treat the so-called Second Book of Esdras. Although counted among the apocryphal books, it seems more to me to be what is technically called pseudopigrapha (“false writings”). It is not recognized by any western church; neither the Roman church nor the Protestants recognize it, although it is annexed as part of an appendix to the Vulgate. Only the Greek and Russian Orthodox accept it as Scripture. If I recall correctly, it is actually made up of three different writings all from the 2nd or 3rd Centuries of the Christian era; it’s not “Old Testament”or “Hebrew Scripture”, at all! So what does one do with it? Here it is in the lectionary for All Saints Day for obvious reasons, but what does one do with it?

I have to admit that I’m not sure how to treat the so-called Second Book of Esdras. Although counted among the apocryphal books, it seems more to me to be what is technically called pseudopigrapha (“false writings”). It is not recognized by any western church; neither the Roman church nor the Protestants recognize it, although it is annexed as part of an appendix to the Vulgate. Only the Greek and Russian Orthodox accept it as Scripture. If I recall correctly, it is actually made up of three different writings all from the 2nd or 3rd Centuries of the Christian era; it’s not “Old Testament”or “Hebrew Scripture”, at all! So what does one do with it? Here it is in the lectionary for All Saints Day for obvious reasons, but what does one do with it? I want you for just a minute to close your eyes. Just sit back and relax, and imagine that you are hearing not my voice, but the voice of your beloved, the voice of the one person in this world who loves you more than any other . . . .

I want you for just a minute to close your eyes. Just sit back and relax, and imagine that you are hearing not my voice, but the voice of your beloved, the voice of the one person in this world who loves you more than any other . . . .  The Jews, John tells us, disputed among themselves as Jesus was delivering the lengthy dissertation on bread from which these statements come. Earlier he had introduced this idea that his flesh was bread to be eaten by his followers: “I am the living bread that came down from heaven. Whoever eats of this bread will live for ever; and the bread that I will give for the life of the world is my flesh.” (v. 51) The very idea of consuming human flesh is off-putting, even disgusting, and would have been extremely objectionable to the Jews; no wonder they grumbled and mumbled, complained and disputed. Even as a metaphor, the statement demands a lot from Jesus’ followers!

The Jews, John tells us, disputed among themselves as Jesus was delivering the lengthy dissertation on bread from which these statements come. Earlier he had introduced this idea that his flesh was bread to be eaten by his followers: “I am the living bread that came down from heaven. Whoever eats of this bread will live for ever; and the bread that I will give for the life of the world is my flesh.” (v. 51) The very idea of consuming human flesh is off-putting, even disgusting, and would have been extremely objectionable to the Jews; no wonder they grumbled and mumbled, complained and disputed. Even as a metaphor, the statement demands a lot from Jesus’ followers!

A year ago I was in Ireland, camped out in a cottage outside of the village of Banagher, County Offaly, on sabbatical. As my study project, I was translating old Irish hymns into metrical, rhyming English such that they could be sung to the music of the original. The hymns were published in the early 20th Century in a collection titled Dánta Dé Idir Sean agus Nuadh compiled by Uná ní Ógáin. Dánta Dé includes a communion hymn which elaborates on John’s story of the wedding feast; it is entitled The Blessed Wedding at Cana and is attributed to Maighréad ní Annagáin. I found I could not directly translate the hymn, so instead I wrote a poem of my own. Reading this story today, I recall working on that piece and offer it again.

A year ago I was in Ireland, camped out in a cottage outside of the village of Banagher, County Offaly, on sabbatical. As my study project, I was translating old Irish hymns into metrical, rhyming English such that they could be sung to the music of the original. The hymns were published in the early 20th Century in a collection titled Dánta Dé Idir Sean agus Nuadh compiled by Uná ní Ógáin. Dánta Dé includes a communion hymn which elaborates on John’s story of the wedding feast; it is entitled The Blessed Wedding at Cana and is attributed to Maighréad ní Annagáin. I found I could not directly translate the hymn, so instead I wrote a poem of my own. Reading this story today, I recall working on that piece and offer it again. OK. I know I shouldn’t get into this . . . I know that someone is going to give me a hard time; I can almost predict that someone will tell me they are planning to “leave the church” over this. But here goes.

OK. I know I shouldn’t get into this . . . I know that someone is going to give me a hard time; I can almost predict that someone will tell me they are planning to “leave the church” over this. But here goes.  Reading these oh-so-familiar words in the introduction to John’s Gospel, I remember other words I read on another blog yesterday:

Reading these oh-so-familiar words in the introduction to John’s Gospel, I remember other words I read on another blog yesterday: