From the Letter to the Ephesians:

So [Christ] came and proclaimed peace to you who were far off and peace to those who were near; for through him both of us have access in one Spirit to the Father. So then you are no longer strangers and aliens, but you are citizens with the saints and also members of the household of God, built upon the foundation of the apostles and prophets, with Christ Jesus himself as the cornerstone. In him the whole structure is joined together and grows into a holy temple in the Lord; in whom you also are built together spiritually into a dwelling-place for God.

(From the Daily Office Lectionary – Ephesians 2:17-22 (NRSV) – January 17, 2013.)

For many years, I have rather liked Paul’s citizenship metaphor for our participation in the household of God. It made sense . . . but I’m not sure it makes sense any longer because I’m not sure we understand any longer what citizenship is!

For many years, I have rather liked Paul’s citizenship metaphor for our participation in the household of God. It made sense . . . but I’m not sure it makes sense any longer because I’m not sure we understand any longer what citizenship is!

A historical review of the understanding of citizenship going back to the earliest Greek city-states suggests that there are two basic classical theories: the humanist and the individualist.

The humanist conception of citizenship emphasizes our political nature viewing citizenship as an active process of involvement in the affairs of the state. Under this theory, being a citizen means being active in government affairs; citizens and the government are mutually interrelated. An ideal citizen is one who exhibits good civic behavior and acts out of a commitment to civic duty and virtue. The individualist view, on the other hand, assumes that human beings act not out of civic morality, but out of enlightened self-interest. Citizens are seen as essentially passive politically, as sovereign, morally autonomous beings primarily focused on their own economic betterment. Nonetheless, between citizen and state there is a mutuality of obligation. The citizen is expected to pay taxes, obey the law, engage in business, and defend the nation if it comes under attack; the state has the duty to respect and protect the civil and political rights of the citizen.

The Enlightenment vision of citizenship, which gave rise to modern democratic republics like the United States, incorporates both of these classical models.

At the recent Emergence Christianity conversation, Phyllis Tickle used the examples of a beehive and an anthill to contrast traditional and emerging notions of leadership. Beehives are hierarchies with a controlling matriarch, the “queen”, and all workers exist to serve her needs and follow her direction. Anthills have “queens” but they are non-directive. The ant queen serves her function in the community (producing young) but does not control what others do. Instead, anthills exhibit a collective intelligence which does not depend upon the decision-making or direction of any one individual or even small group of individuals; in fact, there are no individuals, only the collective. Ms. Tickle suggested that because of the increase in knowledge and communication, which the internet and social media perhaps exemplify best, human society is moving away from the beehive and toward the anthill. One might say we are becoming “ant-i-fied”.

She may be right . . . and that’s the problem with the “citizenship” metaphor now. Neither the beehive nor the anthill understands the concept of “citizen” and if modern human society has been or is becoming patterned on either, Paul’s use of the term to describe our relationship with one another and with God in the context of the church becomes meaningless. Furthermore, if we human beings are becoming nothing more than “ants” in a collective intelligence, there is push back against that, and that push back is also counter to the classical notions of citizenship. The reaction to the “ant-i-fying” of human society is equally destructive of the citizenship metaphor because it has emphasized the individual over against society rather than the individual within and mutually related to society.

We are, Paul wrote, citizens with the saints and members of the household of God. If we do not understand what it is to be citizens of a human society, if we are all simply workers in a beehive hierarchy, or faceless units in an anthill collective, or individuals over against a society, can we make sense of this metaphor? Let us hope we can so that our understanding of Paul’s citizenship model will shape not only the church, but our society as well.

====================

A request to my readers: I’m trying to build the readership of this blog and I’d very much appreciate your help in doing so. If you find something here that is of value, please share it with others. If you are on Facebook, “like” the posts on your page so others can see them. If you are following me on Twitter, please “retweet” the notices of these meditations. If you have a blog of your own, please include mine in your links (a favor I will gladly reciprocate). Many thanks!

====================

Father Funston is the rector of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Medina, Ohio.

Does it bother anyone else that as soon as Mrs. Simon’s mother is healed by Jesus she gets up from her sick bed and “begins to serve them”? That has always bothered me. I don’t know why it should. After all, if she’s healed (and one assumes that when Jesus healed someone they were really healed), then there’s no reason for her not to do what she would have done if she’d not been sick in the first place. But . . . it has bothered me. Why, I have thought, should this poor woman who’s been sick have to get out of bed and serve these men?

Does it bother anyone else that as soon as Mrs. Simon’s mother is healed by Jesus she gets up from her sick bed and “begins to serve them”? That has always bothered me. I don’t know why it should. After all, if she’s healed (and one assumes that when Jesus healed someone they were really healed), then there’s no reason for her not to do what she would have done if she’d not been sick in the first place. But . . . it has bothered me. Why, I have thought, should this poor woman who’s been sick have to get out of bed and serve these men? “I don’t know if this story happened, but I know it is true.” One of my favorite stories begins this way. The Gospel accounts do not, but they could . . . .

“I don’t know if this story happened, but I know it is true.” One of my favorite stories begins this way. The Gospel accounts do not, but they could . . . . At the emergence Christianity conversation I took part in at St. Mary’s Cathedral in Memphis, Tennessee, this past weekend a distinction was made between “emergence Christianity” and “inherited Christianity”. Paul’s thesis that “in Christ we have obtained an inheritance” and that this inheritance is “redemption as God’s own people” has brought this to mind. (For the details of this movement and some of its history, the book to read is

At the emergence Christianity conversation I took part in at St. Mary’s Cathedral in Memphis, Tennessee, this past weekend a distinction was made between “emergence Christianity” and “inherited Christianity”. Paul’s thesis that “in Christ we have obtained an inheritance” and that this inheritance is “redemption as God’s own people” has brought this to mind. (For the details of this movement and some of its history, the book to read is  Well! Here we are . . . just a few days ago I mentioned this text in regard to another lectionary reading. I am attending a conference on “emerging Christianity” this week and this text (having come up in that meditation) has been on my mind. There are many among the participants in this conversation who are quite passionate about the “emerging church” movement; they are definitely not “lukewarm”.

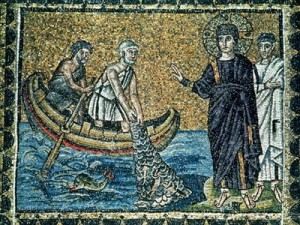

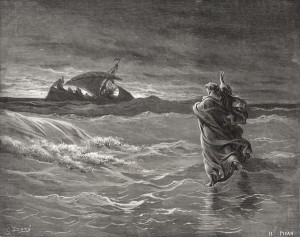

Well! Here we are . . . just a few days ago I mentioned this text in regard to another lectionary reading. I am attending a conference on “emerging Christianity” this week and this text (having come up in that meditation) has been on my mind. There are many among the participants in this conversation who are quite passionate about the “emerging church” movement; they are definitely not “lukewarm”. Jesus walking on the water has always struck me as a very funny story. “Funny” in the sense of “oddly out of place”, although it also has a certain Monty-Python-esque quality to it as well. The fact that it is reported in three of the Gospels – in the synoptic Gospels of Mark and Matthew and here in John – attests to its importance for the early church. John’s version of the story is the simplest, but it contains all the elements – a storm, rough seas, disciples’ fear. Like Mark, John leaves out Matthew’s addition of Peter trying to join Jesus on the surface of the lake.

Jesus walking on the water has always struck me as a very funny story. “Funny” in the sense of “oddly out of place”, although it also has a certain Monty-Python-esque quality to it as well. The fact that it is reported in three of the Gospels – in the synoptic Gospels of Mark and Matthew and here in John – attests to its importance for the early church. John’s version of the story is the simplest, but it contains all the elements – a storm, rough seas, disciples’ fear. Like Mark, John leaves out Matthew’s addition of Peter trying to join Jesus on the surface of the lake.  “I was ready to be sought . . . I said, ‘Here I am, here I am’.” Almost more than anything else in Scripture, these words speak to me of God as not just wanting but needing to be in relationship with creation. I have written elsewhere about my understanding of God as the God who communicates; here is the God who seems almost desperate to be in relationship with his people. God speaks and everything comes in to being; in the beginning was the Word. But what good is speaking, what good is a word, if no one hears it, no one answers it? “Here I am, here I am” seems like a plea to be heard, to be recognized, to be answered. But in our modern society, very few people seem to be answering. Many claim to be seeking, many claim to be “spiritual but not religious,” but few are finding God in the traditional faiths and faith communities.

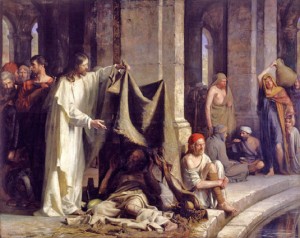

“I was ready to be sought . . . I said, ‘Here I am, here I am’.” Almost more than anything else in Scripture, these words speak to me of God as not just wanting but needing to be in relationship with creation. I have written elsewhere about my understanding of God as the God who communicates; here is the God who seems almost desperate to be in relationship with his people. God speaks and everything comes in to being; in the beginning was the Word. But what good is speaking, what good is a word, if no one hears it, no one answers it? “Here I am, here I am” seems like a plea to be heard, to be recognized, to be answered. But in our modern society, very few people seem to be answering. Many claim to be seeking, many claim to be “spiritual but not religious,” but few are finding God in the traditional faiths and faith communities. This is an old and familiar story, this tale of Christ healing the paralyzed man a the pool at Bethesda. We all know it well. The story continues with a confrontation between the man who has been and the Jewish religious authorities. This healing took place on the Sabbath. The confrontation is over whether it is proper for the man to carry his mat (i.e., perform work) on the Sabbath. The man’s defense is that the person who healed him told him to do so, although he doesn’t know (at the time) who the healer was. Later he learns it was Jesus and identifies him to the priests and scribes.

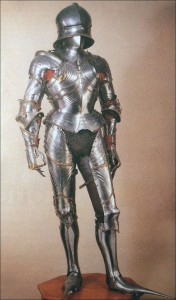

This is an old and familiar story, this tale of Christ healing the paralyzed man a the pool at Bethesda. We all know it well. The story continues with a confrontation between the man who has been and the Jewish religious authorities. This healing took place on the Sabbath. The confrontation is over whether it is proper for the man to carry his mat (i.e., perform work) on the Sabbath. The man’s defense is that the person who healed him told him to do so, although he doesn’t know (at the time) who the healer was. Later he learns it was Jesus and identifies him to the priests and scribes. I am fascinated by this picture of God arming for battle, putting on his breastplate, his helmet, and his mantle, donning the “garments of vengeance.” It is, of course, injustice and evil against which God is arming. St. Paul picked up on the picture painted here by Isaiah when he admonished the Christians in Ephesus:

I am fascinated by this picture of God arming for battle, putting on his breastplate, his helmet, and his mantle, donning the “garments of vengeance.” It is, of course, injustice and evil against which God is arming. St. Paul picked up on the picture painted here by Isaiah when he admonished the Christians in Ephesus: Last week the senior seminarians of the Episcopal Church, those who will graduate in the spring and shortly thereafter be ordained to the transitional diaconate, sat for the General Ordination Examination. This mutli-day test is something like a Bar exam for the clergy of our denomination. Each day, after the testing was concluded, one or more bloggers were posting and commenting up on the questions.

Last week the senior seminarians of the Episcopal Church, those who will graduate in the spring and shortly thereafter be ordained to the transitional diaconate, sat for the General Ordination Examination. This mutli-day test is something like a Bar exam for the clergy of our denomination. Each day, after the testing was concluded, one or more bloggers were posting and commenting up on the questions.