====================

A sermon offered on Fifteenth Sunday after Pentecost (Proper 18B, Track 1, RCL), September 6, 2015, to the people of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Medina, Ohio, where Fr. Funston is rector.

(The lessons for the day are Proverbs 22:1-2,8-9,22-23; Psalm 125; James 2:1-17; Mark 7:24-37. These lessons may be found at The Lectionary Page.)

====================

![]() “Jesus set out and went away to the region of Tyre. He entered a house and did not want anyone to know he was there.” Mark’s Gospel can be infuriating at times. This introduction to the story of the Syrophoenician woman is definitely one of those times, two short sentences which leave us wanting to know so much more. We can, I think, understand why Jesus might not want anyone to know he was in the place; we frequently observe him throughout the Gospels trying to find some “down-time,” some privacy, some solitude to be with God. But why did he set out and go “to the region of Tyre?”

“Jesus set out and went away to the region of Tyre. He entered a house and did not want anyone to know he was there.” Mark’s Gospel can be infuriating at times. This introduction to the story of the Syrophoenician woman is definitely one of those times, two short sentences which leave us wanting to know so much more. We can, I think, understand why Jesus might not want anyone to know he was in the place; we frequently observe him throughout the Gospels trying to find some “down-time,” some privacy, some solitude to be with God. But why did he set out and go “to the region of Tyre?”

Tyre was a Greek commercial center in southern Lebanon. For the Jews of First Century Palestine it was just beyond the northernmost extent of their province; “the region of Tyre” was where Jews and Gentiles frequently interacted, a frankly uncomfortable situation for Jews whose religion and law forbade that, whose racial and religious prejudices informed them that they were God’s chosen and that all other persons were unclean, whose sense of self and national importance required that they separate themselves from Gentiles. It was not the sort of place one would have expected the Jewish Messiah to go. So why is he there?

“He entered a house . . . “ Whose?!? Why!?! There are just all sorts of questions that erupt from those four short words.

Mark leaves us wanting so much more information! It’s infuriating.

Of course, Mark leaves out those details that he doesn’t think important. What’s crucial for Mark is the story of the interaction between Jesus and the Syrophoenician woman, probably the most uncomfortable, the most disturbing story about Jesus in all of the Gospel literature.

The story is simple and brief. A non-Jewish woman who has heard of Jesus’ power as a healer comes seeking aid for her daughter. Mark specifically identifies her as a Syrophoenician, a Greek-speaking resident of what we now call Syria. She has, perhaps, come from Syria to the Mediterranean with her child seeking a better life and now she needs help. Jesus dismisses her; to be honest, he blows her off. “I’m here for the Jewish children,” he says, “not you Gentile dogs.” He’s not just dismissive; he’s rude. He’s not just rude; he’s insulting! “But even the dogs,” she replies in the face of his insult, “even the dogs get the children’s scraps.”

My friend David Henson, an Episcopal priest and journalist, writes of this story:

Jesus uttered an ethnic slur.

To dismiss a desperate woman with a seriously sick child.

In this week’s gospel text, in the Black Lives Matter era, I think we have to start with that disturbing and disorienting fact.

Our immediate response likely is, “Of course not! Jesus couldn’t possibly have uttered a slur!” But Jesus’ exchange with the Syrophoenician woman seems to tell a different story. No matter what theological tap dance can avoid it: Jesus calls the unnamed woman a dog, an ethnic slur common at the time.

To be clear, while there is some debate about the social and cultural dynamics at work here, Jesus holds all the power in this exchange. The woman doesn’t approach with arrogance or a sense of entitlement associated with wealth or privilege. Rather she comes to him in the most human way possible, desperate and pleading for her daughter. And he responds by dehumanizing her with ethnic prejudice, if not bigotry. In our modern terms, we know that power plus prejudice equals racism. (In Patheos “Edges of Faith” Blog.)

I believe David is right to link this story to the refrain “Black Lives Matter” which we have begun to hear with increasing fervor and increasing frequency, because that is exactly what this woman says to Jesus: “Syrophoenician Lives Matter” . . . . and Jesus responds out of his religion which forbade interaction with non-Jews, out of the racial and religious prejudices which informed his society that Jews were God’s chosen and that all other persons were unclean, out of that sense of self and national importance that required that he and all Jews separate themselves from Gentiles. When we hear “Black Lives Matter,” we are likely to do very much the same thing.

More than once I have heard members of my race and economic class respond with the comeback “All lives matter” and at first that made sense to me. Then I read an editorial in which was written:

If I say, “Black lives matter,” and you think I mean, “Black lives matter more than others,” we’re having a misunderstanding.

If I say, “White privilege is real and it means white people have some unearned social advantages just because they’re white,” and you think I mean, “White privilege is real and it means white people should be ashamed of themselves just because they’re white,” we’re having a misunderstanding.

If I say, “We have a problem with institutionalized racism in our legal system,” and you think I mean, “We have a problem with everyone being racist in our legal system,” we’re having a misunderstanding.

If we are having these misunderstandings, where are they coming from and what can we do about them?

(Note: The source is an internet meme seen on Facebook and Pinterest; the origin of the text is unknown.)

“Sir,” said the Syrophoenician woman, “even the dogs under the table eat the children’s crumbs. [We are having a misunderstanding, where is it coming from and what can we do about it?]”

I came to realize “All lives matter” is a retort that dilutes and even negates the assertion that “black lives matter.”

We generally do not respond in that way when others make claim to particularity. When Jesus says, “Blessed are the poor,” we don’t rise up and insist “No, Jesus, blessed is everybody in every economic class.” When the Buddha says, “The enlightened one must delight in the forest,” we don’t dismiss him with “No, Siddhartha, one should delight in the desert and the meadow, as well” We don’t because we realize that their specificity has a point; the specific does not negate the general or the other, but it does highlight the particular. “Blessed are the poor” highlights the plight of those who lack; “Delight in the forest” draws attention to the interconnections of all life.

“Black lives matter” underscores the sad fact that, for many, black lives do NOT matter, and offering “All lives matter” as a response invalidates that specific and particular realization. Of course, all lives matter, but in our contemporary social circumstance specifically noting that black lives matter has particular currency and validity.

To respond “All lives matter” drowns the specificity of the assertion in an undifferentiated sea of sameness and unrecognizability which we know darn good and well really does not exist! The claim of the particular cannot be overwhelmed by the flood of the undefined, and we are wrong to respond in that way, just as wrong as Jesus came to know himself to have been in calling the woman a dog!

Early last week the news media and social media were flooded with pictures of three-year-old Aylan Kurbi, and later with photos of his five-year-old brother Galip and their mother Rehan. Like the woman in our Gospel story today, a mother and her children come from Syria to the Mediterranean seeking a better life, three refugees fleeing their own war-torn and atrocity-ravaged country, trying to get to Europe and from there to Canada where Aylan’s aunt and uncle live and were preparing a new life for them. They didn’t make it. Whatever vessel they were in capsized and they drowned, Aylan’s little body washing up onto the beach of a Turkish resort.

As photos of his lifeless body laying face down in the sand made their way instantaneously around the world, an international hew and cry was heard; in a phrase, the world said, “Refugees’ lives matter! Syrian lives matter!” In response to the death of that one, specific little boy, no one was heard to say, “All lives matter” . . . .

As photos of his lifeless body laying face down in the sand made their way instantaneously around the world, an international hew and cry was heard; in a phrase, the world said, “Refugees’ lives matter! Syrian lives matter!” In response to the death of that one, specific little boy, no one was heard to say, “All lives matter” . . . .

It is easy for us to look across the wide ocean to the Middle East and Europe, and diagnose the social ills, the evil spirits, and the political injustices that led to Aylan’s death; it is less easy for us to acknowledge and diagnose in our own country what Presiding Bishop Katharine and President Jennings called the “structures that bear witness to unjust centuries of the evils of white privilege, systemic racism, and oppression that are not yet consigned to history.” (A Letter to the Episcopal Church. Note: The letter was read in full to the congregation prior to the service.) As Jesus noted, it is much easier to see our neighbors’ problems than our own, but he advises us: “First take the log out of your own eye, and then you will see clearly to take the speck out of your neighbor’s eye.” (Lk 6:41-42, cf Mt 7:4-5)

Mark’s Gospel can be infuriating at times, his ending to the story of the Syrophoenician woman no less so than its introduction. Jesus listened to the Syrophoenician woman, heard the truth of her Gentile reality, and realized the brokenness of his own Jewish milieu: “For saying that,” he tells her, “you may go – the demon has left your daughter.” Going home she finds that to be so and that’s where Mark ends the tale; he gives us not a single additional detail. In the next paragraph, Jesus is forty miles away somewhere east of the Sea of Galilee in the region of the Decapolis, another place with that troublesome intermixture of Jews and Gentiles.

While he is there, another soul in need of help is brought to him, a deaf man with a speech impediment. Mark, having been so careful in the last story to make sure that his readers understand that the woman seeking help for her daughter was a Gentile, completely ignores this man’s ethnicity; but Mark leaves out details that he considers unimportant. Although this story takes place in exactly the same sort of social situation as the last – Jews and Gentiles living side-by-side in that uneasy mix, the Jews here no less bound by those laws of separation, no less steeped in those racial and religious prejudices of chosenness and uncleanness – those differences no longer matter. Jesus’ eyes and ears and heart having been opened by the Syrophoenician woman’s plea; he ministers to the deaf man without regard to whether he is Jew or Gentile. He “put his fingers into his ears, and he spat and touched his tongue. Then looking up to heaven, he sighed and said to him, ‘Ephphatha,’ that is, ‘Be opened.’” I wonder if he thought about how his own understanding of his messianic ministry had been opened up by the woman in Tyre.

“Racism will not end with the passage of legislation alone; it will also require a change of heart and thinking,” our leaders quoted AME Bishop Jackson. It will require that our ears be opened, that we remove the logs from our eyes, and that we confess and repent of the sin of racism, including those times when we have simply ignored it, tolerated it, accepted it, or even unknowingly benefited from it. And lest any of us think that we have nothing in this way to confess, just ponder briefly the words we heard from James’ epistle this morning:

If a person with gold rings and in fine clothes comes into your assembly, and if a poor person in dirty clothes also comes in, and if you take notice of the one wearing the fine clothes and say, “Have a seat here, please,” while to the one who is poor you say, “Stand there,” or, “Sit at my feet,” have you not made distinctions among yourselves, and become judges with evil thoughts?

[Silence]

“A good name is to be chosen rather than great riches, and favor is better than silver or gold. The rich and the poor[, Jews and Gentiles, blacks and whites, women and men, Syrians and Europeans, Christians and Muslims] have this in common: the Lord is the maker of them all.”

Yes, all lives matter.

All lives matter because . . . .

Black lives matter.

Syrian lives matter.

Refugees’ lives matter.

Aylan Kurbi’s life mattered.

The Syrophoenician woman’s daughter’s life mattered.

“Even the dogs under the table eat the children’s crumbs,” and “those who are generous are blessed, for they share their bread with the poor.”

Let us understand and affirm that the call to pray and act for racial reconciliation, to pray and act for an end to racism in our world and in our country, is integral to our witness to the Gospel of Jesus Christ and to our living into the demands of our Baptismal Covenant. “[We] do well if [we] really fulfill the royal law according to the scripture, ‘You shall love your neighbor as yourself.'”

Let us pray:

Grant, O God, that your holy and life-giving Spirit may so move every human heart and especially the hearts of the people of this land, that barriers which divide us may crumble, suspicions disappear, and hatreds cease; that our divisions being healed, we may live in justice and peace; through Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen. (Prayer for Social Justice, BCP 1979, page 823)

====================

A request to my readers: I’m trying to build the readership of this blog and I’d very much appreciate your help in doing so. If you find something here that is of value, please share it with others. If you are on Facebook, “like” the posts on your page so others can see them. If you are following me on Twitter, please “retweet” the notices of these meditations. If you have a blog of your own, please include mine in your links (a favor I will gladly reciprocate). Many thanks!

====================

Father Funston is the rector of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Medina, Ohio.

“This is neither the time nor the place . . . .”

“This is neither the time nor the place . . . .”  In the Education for Ministry program, the first year is spent reading the Old Testament, parts of which can be as dull as dirt! There are those long lists of genealogies, long catalogues of tribes and families, the lengthy and detailed instructions for making and erecting the tabernacle that the Hebrews carried along with them in the desert and, of course, a description of the Temple which Solomon built. In our EfM group, we sort of got into a habit of not reading those parts, of just acknowledging they were there but sort of skipping lightly over them. But it is there, earlier in the First Book of Kings from which our First Lesson is taken, a description of the building in which, in today’s lesson, Solomon places the Ark of the Covenant. Solomon’s Temple (the “First Temple”) was massive; it wasn’t really very big, but it was solid and substantial. It was built of huge blocks of solid stone; it had support beams made of whole cedar trees; it had immense fixtures and columns made of solid bronze and gold. In a word, it was a fortress!

In the Education for Ministry program, the first year is spent reading the Old Testament, parts of which can be as dull as dirt! There are those long lists of genealogies, long catalogues of tribes and families, the lengthy and detailed instructions for making and erecting the tabernacle that the Hebrews carried along with them in the desert and, of course, a description of the Temple which Solomon built. In our EfM group, we sort of got into a habit of not reading those parts, of just acknowledging they were there but sort of skipping lightly over them. But it is there, earlier in the First Book of Kings from which our First Lesson is taken, a description of the building in which, in today’s lesson, Solomon places the Ark of the Covenant. Solomon’s Temple (the “First Temple”) was massive; it wasn’t really very big, but it was solid and substantial. It was built of huge blocks of solid stone; it had support beams made of whole cedar trees; it had immense fixtures and columns made of solid bronze and gold. In a word, it was a fortress! So this is a very familiar story, right? Actually, two very familiar stories. We all know about the feeding of the 5,000. All four gospels – Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John – tell it with slightly varying details. We all know about Jesus walking on the water. Three of the four gospels – Mark, Luke, and John – include that tale, again with slightly varying details. We sometimes mix up those variations, but basically the stories are the same so no big deal.

So this is a very familiar story, right? Actually, two very familiar stories. We all know about the feeding of the 5,000. All four gospels – Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John – tell it with slightly varying details. We all know about Jesus walking on the water. Three of the four gospels – Mark, Luke, and John – include that tale, again with slightly varying details. We sometimes mix up those variations, but basically the stories are the same so no big deal.

Why do people in church seem like cheerful, brainless tourists on a packaged tour of the Absolute? On the whole, I do not find Christians, outside of the catacombs, sufficiently sensible of conditions. Does anyone have the foggiest idea what sort of power we so blithely invoke? Or, as I suspect, does no one believe a word of it? The churches are children playing on the floor with their chemistry sets, mixing up a batch of TNT to kill a Sunday morning. It is madness to wear ladies’ straw hats and velvet hats to church; we should all be wearing crash helmets. Ushers should issue life preservers and signal flares; they should lash us to our pews. For the sleeping god may wake someday and take offense, or the waking god may draw us out to where we can never return. (Annie Dillard, Teaching a Stone to Talk: Expeditions and Encounters [New York: Harper & Row, 1982], pp. 40-41.)

Why do people in church seem like cheerful, brainless tourists on a packaged tour of the Absolute? On the whole, I do not find Christians, outside of the catacombs, sufficiently sensible of conditions. Does anyone have the foggiest idea what sort of power we so blithely invoke? Or, as I suspect, does no one believe a word of it? The churches are children playing on the floor with their chemistry sets, mixing up a batch of TNT to kill a Sunday morning. It is madness to wear ladies’ straw hats and velvet hats to church; we should all be wearing crash helmets. Ushers should issue life preservers and signal flares; they should lash us to our pews. For the sleeping god may wake someday and take offense, or the waking god may draw us out to where we can never return. (Annie Dillard, Teaching a Stone to Talk: Expeditions and Encounters [New York: Harper & Row, 1982], pp. 40-41.) On Wednesday night, America witnessed what happens when that chronic illness is augmented by the acute and opportunistic disease of easy unfettered unregulated unrestricted access to firearms. A 21-year-old white man named Dylann Roof with a history of racism planned and carried out the murders of nine black men and women worshiping in their church, Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, South Carolina; four of those who died were pastors of the church, including the senior pastor Clementa Pinckney, who was also a South Carolina state senator.

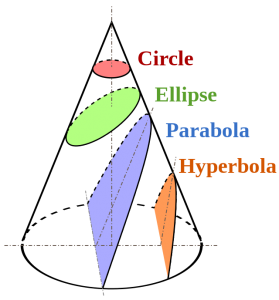

On Wednesday night, America witnessed what happens when that chronic illness is augmented by the acute and opportunistic disease of easy unfettered unregulated unrestricted access to firearms. A 21-year-old white man named Dylann Roof with a history of racism planned and carried out the murders of nine black men and women worshiping in their church, Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, South Carolina; four of those who died were pastors of the church, including the senior pastor Clementa Pinckney, who was also a South Carolina state senator.  Before we tackle today’s lessons from Scripture, we’re going to recall (or perhaps learn for the first time) something from geometry class. First, I want you to envision a cone. You know what a cone is: A cone is a three-dimensional geometric shape that tapers smoothly from a flat base to a point called the apex or vertex; or another way of defining it is the solid object that you get when you rotate a right triangle around one of its two short sides. So, envision one of those.

Before we tackle today’s lessons from Scripture, we’re going to recall (or perhaps learn for the first time) something from geometry class. First, I want you to envision a cone. You know what a cone is: A cone is a three-dimensional geometric shape that tapers smoothly from a flat base to a point called the apex or vertex; or another way of defining it is the solid object that you get when you rotate a right triangle around one of its two short sides. So, envision one of those.  As I read the lessons for today, I had one of those weird little flashes of memory when some small bit of trivial knowledge you had forgotten you knew floats to the surface . . . . In this case it was something from my 9th Grade American History class. My American History teacher loved to fill us up with the minutiae of our country’s past and the one that came to mind is the debate over what to call the President of the United States: the Founders had to determine how the president was to be introduced. There were, apparently, some who favored “His Democratic Majesty, by the Grace of God, President of the United States.” Other senators recommended “His Elective Majesty” and John Adams recommended the title: “His Highness, the President of the United States and Protector of their Liberties.” All of this embarrassed George Washington who would have none of it; he wanted simply to be called “the President of the United States” and to be addressed as “Mr. President.” And thus it has been since then. The American president doesn’t even get “Your Excellency” as the presidents of other nations do.

As I read the lessons for today, I had one of those weird little flashes of memory when some small bit of trivial knowledge you had forgotten you knew floats to the surface . . . . In this case it was something from my 9th Grade American History class. My American History teacher loved to fill us up with the minutiae of our country’s past and the one that came to mind is the debate over what to call the President of the United States: the Founders had to determine how the president was to be introduced. There were, apparently, some who favored “His Democratic Majesty, by the Grace of God, President of the United States.” Other senators recommended “His Elective Majesty” and John Adams recommended the title: “His Highness, the President of the United States and Protector of their Liberties.” All of this embarrassed George Washington who would have none of it; he wanted simply to be called “the President of the United States” and to be addressed as “Mr. President.” And thus it has been since then. The American president doesn’t even get “Your Excellency” as the presidents of other nations do.