====================

A sermon offered on the Third Sunday after Pentecost, June 14, 2015, to the people of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Medina, Ohio, where Fr. Funston is rector.

(The lessons for the day are 1 Samuel 15:34-16:13; Psalm 20; 2 Corinthians 5:6-17; and Mark 4:26-34. These lessons can be read at The Lectionary Page.)

====================

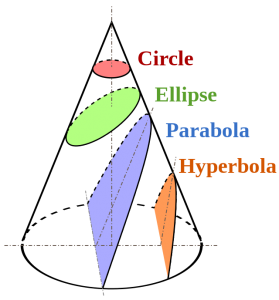

Before we tackle today’s lessons from Scripture, we’re going to recall (or perhaps learn for the first time) something from geometry class. First, I want you to envision a cone. You know what a cone is: A cone is a three-dimensional geometric shape that tapers smoothly from a flat base to a point called the apex or vertex; or another way of defining it is the solid object that you get when you rotate a right triangle around one of its two short sides. So, envision one of those.

Before we tackle today’s lessons from Scripture, we’re going to recall (or perhaps learn for the first time) something from geometry class. First, I want you to envision a cone. You know what a cone is: A cone is a three-dimensional geometric shape that tapers smoothly from a flat base to a point called the apex or vertex; or another way of defining it is the solid object that you get when you rotate a right triangle around one of its two short sides. So, envision one of those.

Now, envision a one-point thick plane slicing through the cone and envision the plane as being exactly parallel to the slope of the cone, or more technically, parallel to a plane which is tangential to the cone’s surface.

Where the plane and the cone intersect, there is now a U-shaped, two-dimensional, mirror-symmetrical curve called a “parabola.” If take that curve, invert it, and rotate it through 360 degrees, we create a “parabolic bowl.” Astronomers mirror-coat such bowls and use them in their telescopes because they reflect light inward to a common point and amplify its intensity; parabolic reflector telescopes make whatever they are looking at clearer to see. Parabolic microphones work the same way with sound.

OK… why am I telling you this?

That curve, a “parabola,” was given its name by Apollonius of Perga, a 3rd Century B.C.E. mathematician, who put together two Greek words: para, meaning “along side,” and ballein, meaning “to throw” or “to place.” The plane which cuts the parabolic curve from the cone is placed (or thrown) alongside (parallel to) the plane tangent to the cone and the curve is created.

The English word parable, which describes these stories of Jesus (and others), is derived from exactly the same original Greek words. Parables are not just cute stories; they are extended metaphors. When someone tells a parable, they are throwing (ballein) one image alongside (para) another as away to illuminate our understanding; like a parabolic mirror or a parabolic microphone, their purpose is to focus our attention so as to lead to greater understanding.

So now we have two parables in today’s gospel, two short stories which are meant to help us understand the kingdom of God. Not “heaven”! Not some mythical place of eternal reward to look forward to after we die, but the kingdom of God which Jesus told us “has come near” and which we pray (some of us) everyday will “come on earth as it is in heaven,” the kingdom of God which is a present, if not yet fully comprehended, reality.

To what can we compare the kingdom of God? Seed scattered (actually “thrown”) by an unobservant and unaware person, seed which takes root and grows when the sower isn’t watching and in ways the sower cannot understand, seed which then produces a crop to the benefit of this ignorant sower. Or, alternatively, to a grain of mustard which also grows in a mysterious way to become a giant bush in which all the birds can make their nests; in fact, the sort of mustard of which Jesus would have been speaking completely takes over the soil in which it is grown – it is an invasive weed whose roots spread in great profusion so that nothing else can grow with it.

Thrown alongside our incomplete picture of the kingdom of God, what can we learn from these parables? What further understanding is parabolically illuminated?

Let’s ponder that question while we turn our attention to today’s Old Testament lesson from the First Book of Samuel. Many commentaries will tell you today’s reading begins the story of David as King of Israel, but that’s not really so. At best, it is the story of David’s first anointing, privately with only his family present, as a potential king in ancient Israel; he will be anointed again, publicly, as king over Judah, in the second chapter of Second Samuel and then again publicly as king over the rest of Israel in the fifth chapter. This isn’t the beginning of David’s story; it is really a tangent, an excursus from Saul’s story, from the story of Saul’s decline and eventual failure as Israel’s first king.

Note the way the lesson begins – “Samuel went to Ramah . . . . ” – and then note the way it ends – “Samuel went to Ramah . . . . ” The words are repeated almost verbatim. In Hebrew literature this repetition indicates a sort of parenthetical addition to a main story. It’s as if the story teller were saying, “O let me fill you in on a little backstory” or “Hang on while I tell you this interesting but unrelated bit of information.” German bible scholars coined a term for this; it’s called a wiederholenden Wiederaufnahme, which simply means “repetitive resumption.” “Samuel went to Ramah” – tell your parenthetical story, then pick up the main story again by repeating – “Samuel went to Ramah.” We find examples like this scattered throughout the Old Testament.

So we have the story of David’s private anointing as just an aside to the larger story of King Saul. Like the parables of the scattered grain and the mustard seed, it is a story of the seemingly insignificant. Samuel expected that Jesse’s eldest son, the tall, good-looking Eliab, was God’s chosen, but that wasn’t so; nor was it to be Abinadab, nor Shammah, nor any of the next three. It was the smallest, the youngest, little David, out keeping the sheep and easily forgotten, who was to be the next king.

In the kingdom of God, the least can be the source of greatness, what is unseen, uncomprehended, and not understood can be the source of a great harvest. The measures and standards of the world where size and good-looks, power and influence, status and position determine outcomes are not those of the kingdom of God. So David is anointed . . . . and then “Samuel went on to Ramah” and the story of Saul continues.

The story of David’s private anointing in his father Jesse’s home is like a little seed planted in the reader’s mind, a little seed planted in Israel’s history. For the rest of the story of Saul, who doesn’t die for another fifteen chapters, as Saul descends into physical, mental, and spiritual illness, as he first calls David as a soothing friend and companion but soon turns against him as his rival and eventual replacement, this little seed of David’s private anointing will take root and grow. He will publicly become king and his kingship will blossom, his kingdom will grow, and under the reign of his son Solomon it will be an earthly empire. Eventually, his descendant Jesus of Nazareth will be born. In God’s kingdom, the seed planted in Jesse’s home will slowly grow until in the incarnation of God in Jesus as the babe of Bethlehem, in his life, death, resurrection, and ascension the kingdom of God will come near and Jesus will reign in heaven and on earth, a kingdom that will never end, growing in ways we cannot see and cannot understand, spreading like a mustard bush, producing a yield ripe for harvest.

To what can we compare the kingdom of God and what parable can we use for it? It grows, in ways we cannot see and cannot comprehend; from small beginnings it spreads its branches until everyone can find shelter in them. In our prayer book office of morning prayer there is a wonderful prayer for mission written by Bishop Charles Henry Brent which begins with these words: “Lord Jesus Christ, you stretched out your arms of love on the hard wood of the cross that everyone might come within the reach of your saving embrace . . . .” I have a friend who dislikes this prayer; it is, he insists, “simplistic transactional theology.” I have to admit that I don’t even know what he means when he says that, but my answer to him is, “It’s not theology; it’s prayer . . . and it’s poetry, parabolic poetry.” The prayer, like a telescope with a parabolic mirror, like a parabolic microphone, like the parables of Jesus, focuses our attention on our place and our mission as followers of Jesus. Like the wide-spreading branches of the mustard bush, Jesus’ arms spread wide inviting all to take shelter.

What began as the small seed of the private anointing of David in the home of Jesse the Bethlehemite has come to fruition in his ancestor Jesus, who (as Paul reminds us) is the “one has died for all . . . so that those who live might live no longer for themselves,” but rather live as “a new creation: everything old has passed away; see, everything has become new!”

Bishop Brent’s prayer for mission concludes with this petition: “So clothe us in your Spirit that we, reaching forth our hands in love, may bring those who do not know you to the knowledge and love of you . . . .” We may not see and we may not understand how the seed germinates, how it grows, how “first the stalk, then the head, then the full grain in the head” appear, but now, and like the sower in the parable, it is time for us to go in with our sickle, with our hands reaching forth in love, because the harvest has ready. Amen.

====================

A request to my readers: I’m trying to build the readership of this blog and I’d very much appreciate your help in doing so. If you find something here that is of value, please share it with others. If you are on Facebook, “like” the posts on your page so others can see them. If you are following me on Twitter, please “retweet” the notices of these meditations. If you have a blog of your own, please include mine in your links (a favor I will gladly reciprocate). Many thanks!

====================

Father Funston is the rector of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Medina, Ohio.

Leave a Reply