====================

A homily offered by the Rev. Dr. C. Eric Funston at the Great Vigil of Easter, Saturday, April 15, 2017, to the people of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Medina, Ohio, where Fr. Funston is rector.

(The lessons for the service are from the Revised Common Lectionary: Genesis 1:1-2:4a; Exodus 14:10-31,15:20-21; Proverbs 8:1-8,19-21,9:4b-6; Zephaniah 3:14-20; Psalm 114; Romans 6:3-11; and St. Matthew 28:1-10. These lessons can be read at The Lectionary Page.)

====================

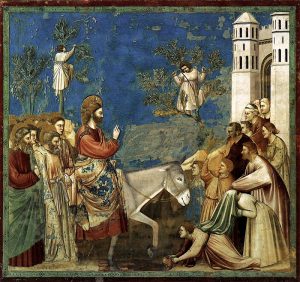

Two weeks ago, the Sunday lectionary treated us to the entire long Gospel lesson of the story of Jesus’ raising of Lazarus and then last week the Daily Office lectionary repeated it in smaller bits over the course of several days. Last Sunday I suggested that Holy Week and Easter can be conceived as a three-act drama to which the Triumphal Entry of Palm Sunday is an overture.

Two weeks ago, the Sunday lectionary treated us to the entire long Gospel lesson of the story of Jesus’ raising of Lazarus and then last week the Daily Office lectionary repeated it in smaller bits over the course of several days. Last Sunday I suggested that Holy Week and Easter can be conceived as a three-act drama to which the Triumphal Entry of Palm Sunday is an overture.

The Lazarus story, like last Sunday’s Gospel, is part of that overture, the introduction to the three-act drama of celebration in which we have participated this week and in which we have come, this evening, to the third and final act. Lazarus has been much on my mind as we have prepared for this Easter celebration and for the baptisms we have just performed. I believe the story of Lazarus’ raising has much to teach us about what we have done here tonight in this third act, this Baptismal Vigil, this liturgy of welcoming and inclusion.

Lazarus was the brother of Mary and Martha of Bethany; they are a family which figures prominently in the Gospels as friends of Jesus. They are clearly people who believe in Jesus and in his mission, but their belief is much, much more than simply signing on to his program, a new approach to religion. This family really seems to know Jesus; he apparently stayed with them on several occasions. He lodged with them, ate with them, taught in their home. When word is sent to Jesus that Lazarus is ill, Lazarus is described to him as “he whom you love.” (John 11:3) Lazarus and his sisters are close to Jesus; they are practically family, may even be family.

As the story of Lazarus raising is told, the family is described as accompanied by “Jews.” That has always struck me as a bit odd. After all, aren’t they all Jews? Mary, Martha, Lazarus, Jesus, the whole lot of them? Of course they are! So many scholars suggest that we should better understand John’s term Ioudaiou to mean “Judeans,” that is people native to the Jerusalem area; these scholars suggest that Mary, Martha, and Lazarus, like Jesus, were Galileans who had moved to Judea and been accepted into this southern community. This strengthens the suggestion that they may have been members of Jesus’ extended family.

Next, when both of the sisters greet Jesus (Martha’s greeting is earlier in the story), the very first thing each says is, “If you had been here, he wouldn’t have died.” (John 11:21 & 32) Not “Hi, how are you?” Not “Welcome back.” Not “I’m so sorry we have to tell you.” What the sisters say is not really a greeting; it’s an angry, accusative confrontation. “You could have prevented this!”

We’re told that Jesus’ response to this is that he is “greatly disturbed in spirit and deeply moved.” That’s a fine translation, but it’s also a bit misleading. The Greek word rendered “disturbed” very literally means he “snorted with anger”; and the word translated “deeply moved” means “stirred up” and implies a certain physicality, not simply an emotion. Jesus response to the sisters’ confrontations, to Lazarus’ death, to the whole situation is to become indignant and sick to his stomach.

The Lazarus story contains the shortest verse in the New Testament, famously rendered in the King James Version with only two words, “Jesus wept.” Some of the Judeans, John tells us, interpreted this as a sign of Jesus’ love for Lazarus; “See how he loved him!” they said. While I’ve no doubt that that is true, I suggest that, since John describes Jesus as angry and physically sick, we might consider another way to understand what is happening in this story.

We have just baptized four children and, together with them, we have affirmed the Baptismal Covenant beginning with a recitation of the Apostle’s Creed in which we will claim that Jesus, the Son of God, was “conceived by the power of the Holy Spirit and born of the Virgin Mary” (BCP 1979, p 304). In the Nicene Creed, which we recite most Sundays during the Holy Eucharist, we go further and declare that he “became incarnate . . . and was made man,” that is, that he became a flesh-and-blood human being. (BCP 1979, p 358). In the Definition of Chalcedon, which you can find on page 864 of the Prayer Book, the church goes even beyond that and asserts its conviction that Jesus is “truly [human] . . . like us in all respects, apart from sin.”

I believe that standing before that tomb where his beloved friend Lazarus had been buried four days earlier, feeling the anger and frustration of his close friends Mary and Martha, surrounded by Judeans muttering “couldn’t he have prevented this,” and perhaps physically exhausted from traveling from the other side of the Jordan valley where he was when he got the news, Jesus’ humanity hit him like a ton of bricks. In that moment, everything that it meant to be human came crashing in on him: the way human beings settle for easy answers, half-truths, and superficial relationships; the injustice, oppression, and exploitation we impose on one another; the pain, rejection, hunger, and war we endure . . . but, also, the love, friendship, community, family, support, and every other good thing about being a human being; it all come together in that moment standing at that grave.

Why do I think that? Because that’s what I feel every time I stand at a grave. The first time I did that, I was 5-1/2 years old. I remember standing between my mother and my paternal grandmother watching two members of the US Army fold the flag that had draped my father’s coffin, feeling loss, grief, anger, confusion, and emotions I couldn’t even name. But there was also the love of family, pride in my father’s military service, a sense of community with extended family and friends, all the comfort that comes from our common humanity. And every time I have stood beside a grave, I have felt that again, and I can surely imagine that our Lord experienced something very like that. No wonder Jesus – the sorrowful-but-also-angry and stirred-up Jesus, the knowing-he-too-might-soon-be-dead Jesus, the fully-human, like-us-in-all-respects Jesus – wept.

We should feel that same way when we welcome a new member into the household of God through the Sacrament of Baptism. Symbolically, baptism is burial; in the oldest tradition of the church, full immersion baptism, we go down under the water in the same way a body is buried in the earth, then we come up out of the water as Lazarus came from his tomb, as Jesus came from his grave. Baptism is death, burial, and restoration to life all encapsulated in one short liturgical act. As St. Paul asks in his letter to the Romans which was read just a few minutes ago, “Do you not know that all of us who have been baptized into Christ Jesus were baptized into his death?” The Prayer Book says in the blessing of the baptismal water, “In it we are buried with Christ in his death.”

St. Paul’s assurance that “if we have been united with him in a death like his, we will certainly be united with him in a resurrection like his,” is echoed by the Prayer Books bold promise that by baptism we share in Jesus’ resurrection, and that “through it we are reborn by the Holy Spirit.” (BCP 1979, p 306) As Jesus called for Lazarus to be unbound from his funeral wrappings, as Jesus himself rose and set aside his shroud, through Holy Baptism our Lord calls us “from the bondage of sin into everlasting life” (ibid), into a new life of full humanity joined with those whom the Psalmist describes as having “clean clean hands and a pure heart, [those] who have not pledged themselves to falsehood nor sworn by what is a fraud, [those who] shall receive a blessing from the Lord and a just reward from the God.” (Ps 24:4-5)

The Creation story in Genesis tells us that “God created humankind in his image, in the image of God he created them; male and female he created them.” (Gn 1:27) The story of the Fall reminds us that somehow that divine likeness has been marred, that on our own we fail to live up to that image; we fail to fully live up to the potential God created in humankind. Through baptism, the divine image is restore; through our baptism into the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus Christ, a process of transformation begins and God restores us to who and what we were meant to be – fully human.

When we baptized these children, we asked them and their baptismal sponsors (and we asked ourselves) some questions which are taken directly from the Apostle’s Creed, to which I referred earlier. These questions began with the words, “Do you believe . . . .”

A few years ago a colleague of mine said that he had once asked his congregation, when reciting the Nicene Creed, to say “We trust in” instead of “We believe in” since the original Greek could have been translated either way. He said he wondered if the church would be less fragmented if we had used “trust.” He suggested that there might have been far less of, “You don’t believe exactly what I believe, so I’m out of here,” or, “You don’t believe exactly what I believe, so you are out of here.” When we ask those questions of baptismal candidates and their Godparents, when we say the creeds ourselves, are expressing a deep affirmation of community whether we say, “We believe in . . .” or “We trust in . . .” Maybe we don’t “believe” exactly the same things that others here believe, but we all trust in the same God.

In that same conversation, another priest objected to what he called the distinction between “faith as trust and faith with content.” “It’s always struck me as a strange distinction,” he said. “If, for example, faith as trust is about relationship [and not about content], it is like someone saying to a prospective marriage partner, ‘I love you and I want to marry you, but I’m not certain who you are.’” I suggested to him, however, and I suggest to you now that this distinction really doesn’t exist, that faith as trust or as relationship necessarily implies and includes “faith with content.” One cannot place trust in another person, such as the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit named in the Creed, without assenting to that person’s existence and properties; to say, “I trust you” or “I love you” and not also agree that you exist makes very little sense.

This is why we ask those questions of baptismal candidates. When we say, “Do you believe in” the three Persons of the Holy Trinity, we are not merely asking if the candidates (and the congregation who join them in answering) are assenting to certain doctrines about them; we are asking if they claim to be in a relationship of trust and love with God the Holy Trinity, and through God with the full community of human beings whom God loves and whom God has redeemed in all that long salvation history that we have heard read from the Hebrew Scriptures this evening. When we baptized these children, when we baptize any new member of the Christian community, we recognize them as part of that fully human community whom God invites to “lay aside immaturity, and live, and walk in the way of insight” (Prov 9:6), whom God promises to save, and gather, and bring home, and restore. (Zeph 3:19-20)

That full human community relationship, I believe, is why Jesus wept. To be sure, he grieved the death of his friend Lazarus, but he knew he was about to do something to change that; there was no reason to cry about that. But that in-rushing crash of realization of what it is to be a human being, of what it is to be fully human, that is enough to make anyone cry. The story of the raising of Lazarus is a story about Jesus’ full humanity, the full humanity he shares with and promises to us, the full humanity which gathered with friends and family at the Last Supper in the first act of this drama of redemption, the full humanity which was arrested and brutalized and crucified in the second act, the full humanity whose Resurrection we celebrate in this, the third act, the feast of Easter. It is into that Easter promise that we have baptized Kadence, Bryce, Hadley, and Joseph this evening. And that is why the Lazarus story figures so prominently in the church’s preparations for Holy Week and Easter, part of the overture of this three-part drama of redemption!

In the words of a popular Franciscan blessing, let us pray that, as these children grow into the full humanity into which they are initiated today, God will bless them with discomfort at easy answers, half-truths, and superficial relationships, so that they may live deep within their hearts; that God will bless them with anger at injustice, oppression, and exploitation of people, so that they may work for justice, freedom, and peace; that God will bless them with tears to shed for those who suffer from pain, rejection, hunger, and war, so that they may reach out their hands to comfort others and turn their pain into joy; and that God bless them with enough foolishness to believe that they can make a difference in this world, so that they can do what others claim cannot be done, to bring justice, kindness, and love to all.

As they have been buried with Christ, they have begun to share in his Resurrection; may God bless them with the gift and the commission to be, like Christ, fully human. Amen.

====================

Father Funston is the rector of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Medina, Ohio.

On Palm Sunday, I suggested that we think of Holy Week and Easter as a three-act drama beginning with an Overture on Palm Sunday. Today, we take part in the first act. The analogy of the Three Holy Days (or “Triduum”) to a play breaks down if we think of ourselves as the “audience.” We are not the audience.

On Palm Sunday, I suggested that we think of Holy Week and Easter as a three-act drama beginning with an Overture on Palm Sunday. Today, we take part in the first act. The analogy of the Three Holy Days (or “Triduum”) to a play breaks down if we think of ourselves as the “audience.” We are not the audience.  Redemption is a drama in three acts – three acts and a brief intermission – today the prelude, the overture, an introduction encapsulating the story to be fleshed out as the action proceeds. Jesus and his companions enter the city of Jerusalem from the east while the Roman governor, Pilate, makes his annual procession into the city in pomp and circumstance from the west.

Redemption is a drama in three acts – three acts and a brief intermission – today the prelude, the overture, an introduction encapsulating the story to be fleshed out as the action proceeds. Jesus and his companions enter the city of Jerusalem from the east while the Roman governor, Pilate, makes his annual procession into the city in pomp and circumstance from the west.  When I was child in my tween years, I spent a lot of time at the Public Library checking out stacks of books, with that wonderful musty library smell, to read under the big oak tree in our back yard on hot summer days. As I was a U.S. history buff both then and now, I gravitated toward a series of children’s books whose titles began with the phrase – “we were there”. For example, We Were There at Lexington and Concord, We Were There at Battle of Gettysburg and my favorite – We Were There at Pearl Harbor. The books had the same two characters – a boy and a girl around my age at the time, who happened to be living right in the middle of these key historic events. They often performed semi-heroic acts and were usually honored or congratulated by some famous person at the end of the book.

When I was child in my tween years, I spent a lot of time at the Public Library checking out stacks of books, with that wonderful musty library smell, to read under the big oak tree in our back yard on hot summer days. As I was a U.S. history buff both then and now, I gravitated toward a series of children’s books whose titles began with the phrase – “we were there”. For example, We Were There at Lexington and Concord, We Were There at Battle of Gettysburg and my favorite – We Were There at Pearl Harbor. The books had the same two characters – a boy and a girl around my age at the time, who happened to be living right in the middle of these key historic events. They often performed semi-heroic acts and were usually honored or congratulated by some famous person at the end of the book.  The First Sunday in Lent … that’s today. That means we get the story of Jesus being chased into the desert by the Holy Spirit after his baptism by John in the River Jordan, the story of Jesus being accosted in the desert by the Tempter (whom Matthew in our Gospel text today also names “the devil” – in Greek the word is diabolos meaning “accuser”), the story of Jesus refusing to give into the three temptations. We always get some version of this story on the First Sunday in Lent. And this year the Lectionary gives us a double-whammy of temptation by linking that familiar gospel tale with the equally family story of Eve and the serpent and the fruit of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, the so-called “apple.”

The First Sunday in Lent … that’s today. That means we get the story of Jesus being chased into the desert by the Holy Spirit after his baptism by John in the River Jordan, the story of Jesus being accosted in the desert by the Tempter (whom Matthew in our Gospel text today also names “the devil” – in Greek the word is diabolos meaning “accuser”), the story of Jesus refusing to give into the three temptations. We always get some version of this story on the First Sunday in Lent. And this year the Lectionary gives us a double-whammy of temptation by linking that familiar gospel tale with the equally family story of Eve and the serpent and the fruit of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, the so-called “apple.” Most of the time when we hear this story of John’s disciples coming to Jesus we focus on John’s question – “Are you the one who is to come, or are we to wait for another?” (Mt 11:3) – and on Jesus’ answer to it which is neither a “yes” nor a “no” but a pointing to the evidence – “the blind receive their sight, the lame walk, the lepers are cleansed, the deaf hear, the dead are raised, and the poor have good news brought to them” (Mt 11:5).

Most of the time when we hear this story of John’s disciples coming to Jesus we focus on John’s question – “Are you the one who is to come, or are we to wait for another?” (Mt 11:3) – and on Jesus’ answer to it which is neither a “yes” nor a “no” but a pointing to the evidence – “the blind receive their sight, the lame walk, the lepers are cleansed, the deaf hear, the dead are raised, and the poor have good news brought to them” (Mt 11:5). Good evening! For those who don’t know me, I am Eric Funston, a priest of the Episcopal Church and rector of St. Paul’s Parish in Medina, Ohio. For those of you who don’t know why I’m preaching here tonight . . . I wish I could tell you! Usually these ordination or installation homily gigs go to someone with whom the new clergy person has had a, shall we say, formative relationship: a former pastor, a seminary professor or a ministry supervisor, an elder minister under whom the new pastor served a curacy, someone responsible for the priestly formation of the new rector. But that doesn’t describe me . . . I am not responsible for George Baum ~ and that is very probably a good thing!

Good evening! For those who don’t know me, I am Eric Funston, a priest of the Episcopal Church and rector of St. Paul’s Parish in Medina, Ohio. For those of you who don’t know why I’m preaching here tonight . . . I wish I could tell you! Usually these ordination or installation homily gigs go to someone with whom the new clergy person has had a, shall we say, formative relationship: a former pastor, a seminary professor or a ministry supervisor, an elder minister under whom the new pastor served a curacy, someone responsible for the priestly formation of the new rector. But that doesn’t describe me . . . I am not responsible for George Baum ~ and that is very probably a good thing! ![Dives and Lazarus. Psalter (Munich Golden Psalter). England [Gloucester?], 1st quarter of the 13th century.](http://thefunstons.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/Lazarus-and-Dives-300x264.jpg) We could, I suppose, spiritualize the story of Lazarus and the rich man. We could, but if we did we would be twisting it out of shape. This is not a spiritual story. This is a bare-knuckled street-brawl of a story about wealth, about money and possessions, about someone who had plenty and about someone who had none. If we are going to honor the biblical text, we cannot spiritualize this tale; we have to deal with it as it is given us, as a story about money.

We could, I suppose, spiritualize the story of Lazarus and the rich man. We could, but if we did we would be twisting it out of shape. This is not a spiritual story. This is a bare-knuckled street-brawl of a story about wealth, about money and possessions, about someone who had plenty and about someone who had none. If we are going to honor the biblical text, we cannot spiritualize this tale; we have to deal with it as it is given us, as a story about money. “Whoever comes to me and does not hate father and mother, wife and children, brothers and sisters, yes, and even life itself, cannot be my disciple. * * * None of you can become my disciple if you do not give up all your possessions.”

“Whoever comes to me and does not hate father and mother, wife and children, brothers and sisters, yes, and even life itself, cannot be my disciple. * * * None of you can become my disciple if you do not give up all your possessions.”