From the Letter to the Ephesians:

In Christ we have also obtained an inheritance, having been destined according to the purpose of him who accomplishes all things according to his counsel and will, so that we, who were the first to set our hope on Christ, might live for the praise of his glory. In him you also, when you had heard the word of truth, the gospel of your salvation, and had believed in him, were marked with the seal of the promised Holy Spirit; this is the pledge of our inheritance towards redemption as God’s own people, to the praise of his glory.

(From the Daily Office Lectionary – Ephesians 1:11-14 (NRSV) – January 14, 2013.)

At the emergence Christianity conversation I took part in at St. Mary’s Cathedral in Memphis, Tennessee, this past weekend a distinction was made between “emergence Christianity” and “inherited Christianity”. Paul’s thesis that “in Christ we have obtained an inheritance” and that this inheritance is “redemption as God’s own people” has brought this to mind. (For the details of this movement and some of its history, the book to read is Emergence Christianity by Phyllis Tickle, who was the keynoter of this weekend’s conversation.)

At the emergence Christianity conversation I took part in at St. Mary’s Cathedral in Memphis, Tennessee, this past weekend a distinction was made between “emergence Christianity” and “inherited Christianity”. Paul’s thesis that “in Christ we have obtained an inheritance” and that this inheritance is “redemption as God’s own people” has brought this to mind. (For the details of this movement and some of its history, the book to read is Emergence Christianity by Phyllis Tickle, who was the keynoter of this weekend’s conversation.)

The conclusion I have drawn from the Memphis Conversation is that “emergent” and “emerging” are essentially meaningless labels, other than that the former is a brand name for the Emergent Village and the latter might describe anything that can be associated with what contemporary historians are calling “The Great Emergence” (a way to describe the current upheaval in western society). If it’s an edgy praxis that somehow claims to be “Christian” and uses glitzy up-to-date technology, it can call itself “emergent” or “emerging” without regard to theological content. (Nadia Bolz-Weber referred to this when suggesting that a label that could be applied to her and to Mark Driscoll is a meaningless term.) There are so many things that claim to be “emergent” or “emerging” (from post-evangelical neo-pentacostalism to a post-theist deconstructed church that claims to be “Christian” without any of the marks of the church) that there really is no substance in these terms; they signify nothing.

Perhaps helpfully another participant has suggested that “Emergence does not modify Christianity. Emergence describes an era; Christianity describes a movement. Whether or not Christianity as we/I know it is modified in this new era remains to be seen.” That may be as far as we can currently go with defining this thing that is happening.

As for the “inherited church” and Paul’s reference to our heritage (with the Ephesians) as followers of Christ, I am struck again by the wisdom of my own Episcopal/Anglican tradition. In the 1880s the bishops of the Episcopal Church looked at the question of organic reunions of the various streams of post-Reformation Christianity and suggested there are really only four things on which Christians would need to be agree. The fourth was “the historic episcopate” which, being bishops, you can sort of understand them thinking important. I value to apostolic office of bishop, but I’m not sure it’s a necessity. The other three, though, really our what we, the “inherited church” offer as foundation for the experimentation in the faith that the “emergent” group is undertaking. What those bishops produced was called a “quadrilateral” and their four points were later affirmed by the gathered bishops of the Anglican Communion and is now referred to as The Chicago/Lambeth Quadrilateral. The substantive content of what the American bishops wrote is:

We do hereby affirm that the Christian unity . . .can be restored only by the return of all Christian communions to the principles of unity exemplified by the undivided Catholic Church during the first ages of its existence; which principles we believe to be the substantial deposit of Christian Faith and Order committed by Christ and his Apostles to the Church unto the end of the world, and therefore incapable of compromise or surrender by those who have been ordained to be its stewards and trustees for the common and equal benefit of all men.

As inherent parts of this sacred deposit, and therefore as essential to the restoration of unity among the divided branches of Christendom, we account the following, to wit:

1. The Holy Scriptures of the Old and New Testaments as the revealed Word of God.

2. The Nicene Creed as the sufficient statement of the Christian Faith.

3. The two Sacraments, — Baptism and the Supper of the Lord, — ministered with unfailing use of Christ’s words of institution and of the elements ordained by Him.

4. The Historic Episcopate, locally adapted in the methods of its administration to the varying needs of the nations and peoples called of God into the unity of His Church. (The Book of Common Prayer – 1979, page 877)

I am quite certain that some among the “emergent” or “emerging” church movement would reject this foundational deposit. I am also quite certain that without at least the first three (as I said, I’m not so certain about the necessity of bishops) the movement cannot be considered “Christian” nor would its embodiment be “church”. I think we can talk about these things critically (for instance, noting that the first does not require a belief in the literal factuality or inerrancy of Scripture, or that the third does not set out a specific theology of the Sacraments, but that both leave open the possibility of a wide variety of understandings). But I do not believe that we can abandon them.

I do not believe that “emerging” means “leaving behind.” It does not mean abandoning our inheritance.

====================

A request to my readers: I’m trying to build the readership of this blog and I’d very much appreciate your help in doing so. If you find something here that is of value, please share it with others. If you are on Facebook, “like” the posts on your page so others can see them. If you are following me on Twitter, please “retweet” the notices of these meditations. If you have a blog of your own, please include mine in your links (a favor I will gladly reciprocate). Many thanks!

====================

Father Funston is the rector of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Medina, Ohio.

Well! Here we are . . . just a few days ago I mentioned this text in regard to another lectionary reading. I am attending a conference on “emerging Christianity” this week and this text (having come up in that meditation) has been on my mind. There are many among the participants in this conversation who are quite passionate about the “emerging church” movement; they are definitely not “lukewarm”.

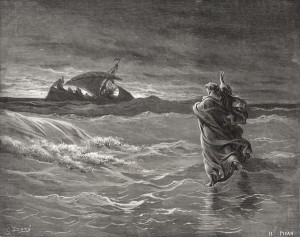

Well! Here we are . . . just a few days ago I mentioned this text in regard to another lectionary reading. I am attending a conference on “emerging Christianity” this week and this text (having come up in that meditation) has been on my mind. There are many among the participants in this conversation who are quite passionate about the “emerging church” movement; they are definitely not “lukewarm”. Jesus walking on the water has always struck me as a very funny story. “Funny” in the sense of “oddly out of place”, although it also has a certain Monty-Python-esque quality to it as well. The fact that it is reported in three of the Gospels – in the synoptic Gospels of Mark and Matthew and here in John – attests to its importance for the early church. John’s version of the story is the simplest, but it contains all the elements – a storm, rough seas, disciples’ fear. Like Mark, John leaves out Matthew’s addition of Peter trying to join Jesus on the surface of the lake.

Jesus walking on the water has always struck me as a very funny story. “Funny” in the sense of “oddly out of place”, although it also has a certain Monty-Python-esque quality to it as well. The fact that it is reported in three of the Gospels – in the synoptic Gospels of Mark and Matthew and here in John – attests to its importance for the early church. John’s version of the story is the simplest, but it contains all the elements – a storm, rough seas, disciples’ fear. Like Mark, John leaves out Matthew’s addition of Peter trying to join Jesus on the surface of the lake.  “I was ready to be sought . . . I said, ‘Here I am, here I am’.” Almost more than anything else in Scripture, these words speak to me of God as not just wanting but needing to be in relationship with creation. I have written elsewhere about my understanding of God as the God who communicates; here is the God who seems almost desperate to be in relationship with his people. God speaks and everything comes in to being; in the beginning was the Word. But what good is speaking, what good is a word, if no one hears it, no one answers it? “Here I am, here I am” seems like a plea to be heard, to be recognized, to be answered. But in our modern society, very few people seem to be answering. Many claim to be seeking, many claim to be “spiritual but not religious,” but few are finding God in the traditional faiths and faith communities.

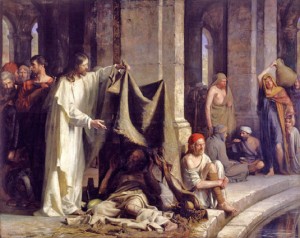

“I was ready to be sought . . . I said, ‘Here I am, here I am’.” Almost more than anything else in Scripture, these words speak to me of God as not just wanting but needing to be in relationship with creation. I have written elsewhere about my understanding of God as the God who communicates; here is the God who seems almost desperate to be in relationship with his people. God speaks and everything comes in to being; in the beginning was the Word. But what good is speaking, what good is a word, if no one hears it, no one answers it? “Here I am, here I am” seems like a plea to be heard, to be recognized, to be answered. But in our modern society, very few people seem to be answering. Many claim to be seeking, many claim to be “spiritual but not religious,” but few are finding God in the traditional faiths and faith communities. This is an old and familiar story, this tale of Christ healing the paralyzed man a the pool at Bethesda. We all know it well. The story continues with a confrontation between the man who has been and the Jewish religious authorities. This healing took place on the Sabbath. The confrontation is over whether it is proper for the man to carry his mat (i.e., perform work) on the Sabbath. The man’s defense is that the person who healed him told him to do so, although he doesn’t know (at the time) who the healer was. Later he learns it was Jesus and identifies him to the priests and scribes.

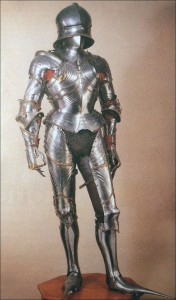

This is an old and familiar story, this tale of Christ healing the paralyzed man a the pool at Bethesda. We all know it well. The story continues with a confrontation between the man who has been and the Jewish religious authorities. This healing took place on the Sabbath. The confrontation is over whether it is proper for the man to carry his mat (i.e., perform work) on the Sabbath. The man’s defense is that the person who healed him told him to do so, although he doesn’t know (at the time) who the healer was. Later he learns it was Jesus and identifies him to the priests and scribes. I am fascinated by this picture of God arming for battle, putting on his breastplate, his helmet, and his mantle, donning the “garments of vengeance.” It is, of course, injustice and evil against which God is arming. St. Paul picked up on the picture painted here by Isaiah when he admonished the Christians in Ephesus:

I am fascinated by this picture of God arming for battle, putting on his breastplate, his helmet, and his mantle, donning the “garments of vengeance.” It is, of course, injustice and evil against which God is arming. St. Paul picked up on the picture painted here by Isaiah when he admonished the Christians in Ephesus: Last week the senior seminarians of the Episcopal Church, those who will graduate in the spring and shortly thereafter be ordained to the transitional diaconate, sat for the General Ordination Examination. This mutli-day test is something like a Bar exam for the clergy of our denomination. Each day, after the testing was concluded, one or more bloggers were posting and commenting up on the questions.

Last week the senior seminarians of the Episcopal Church, those who will graduate in the spring and shortly thereafter be ordained to the transitional diaconate, sat for the General Ordination Examination. This mutli-day test is something like a Bar exam for the clergy of our denomination. Each day, after the testing was concluded, one or more bloggers were posting and commenting up on the questions.

As I read the lesson from Exodus today, there is a bush in my dining room. It’s a four-foot tall evergreen and it’s sort of burning. There are little electrical lights all ablaze all over it. It’s our Christmas tree. (We have a short Christmas tree set on a table because we have three cats. We tried for a couple of years to have a normal size seven-foot tree with these guys, but it was impossible. So, small tree on table.)

As I read the lesson from Exodus today, there is a bush in my dining room. It’s a four-foot tall evergreen and it’s sort of burning. There are little electrical lights all ablaze all over it. It’s our Christmas tree. (We have a short Christmas tree set on a table because we have three cats. We tried for a couple of years to have a normal size seven-foot tree with these guys, but it was impossible. So, small tree on table.) How many places do we go where the Lord is and we do not know it? This story of Jacob reminds me of a song we sang in the Cursillo community where I meant my wife. It’s very pretty, very contemplative, and usually sung as an accompaniment to Holy Communion:

How many places do we go where the Lord is and we do not know it? This story of Jacob reminds me of a song we sang in the Cursillo community where I meant my wife. It’s very pretty, very contemplative, and usually sung as an accompaniment to Holy Communion: