Finally, I am in one place for more than a day or two … but getting here was a 24-hour exercise in frustration!

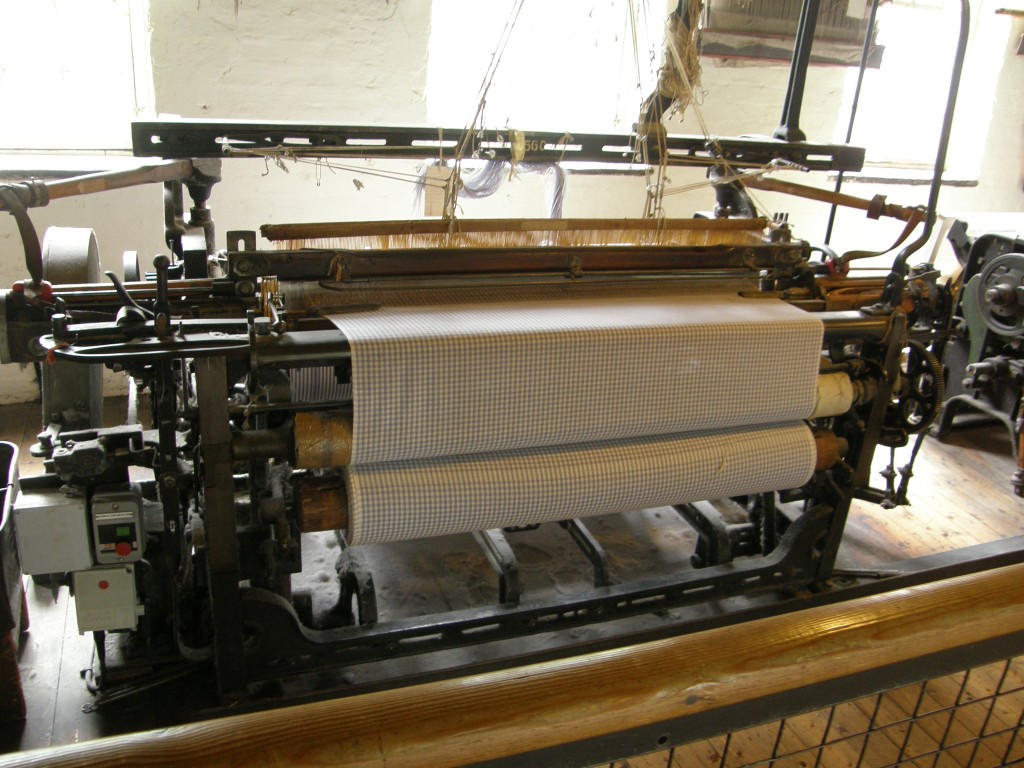

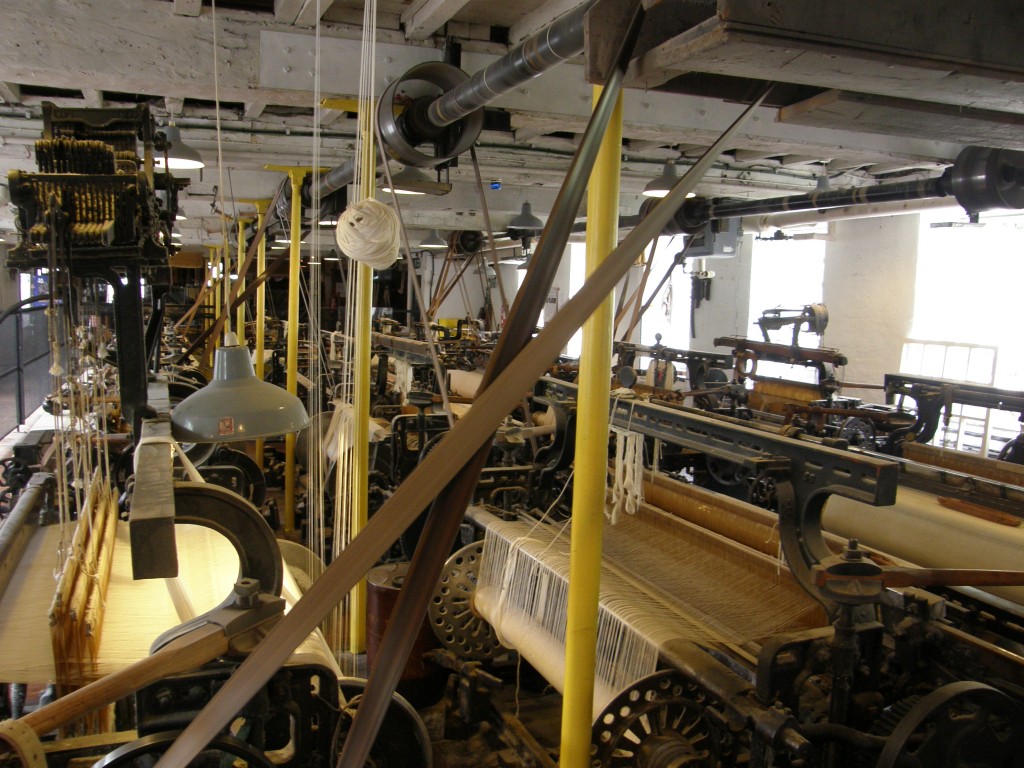

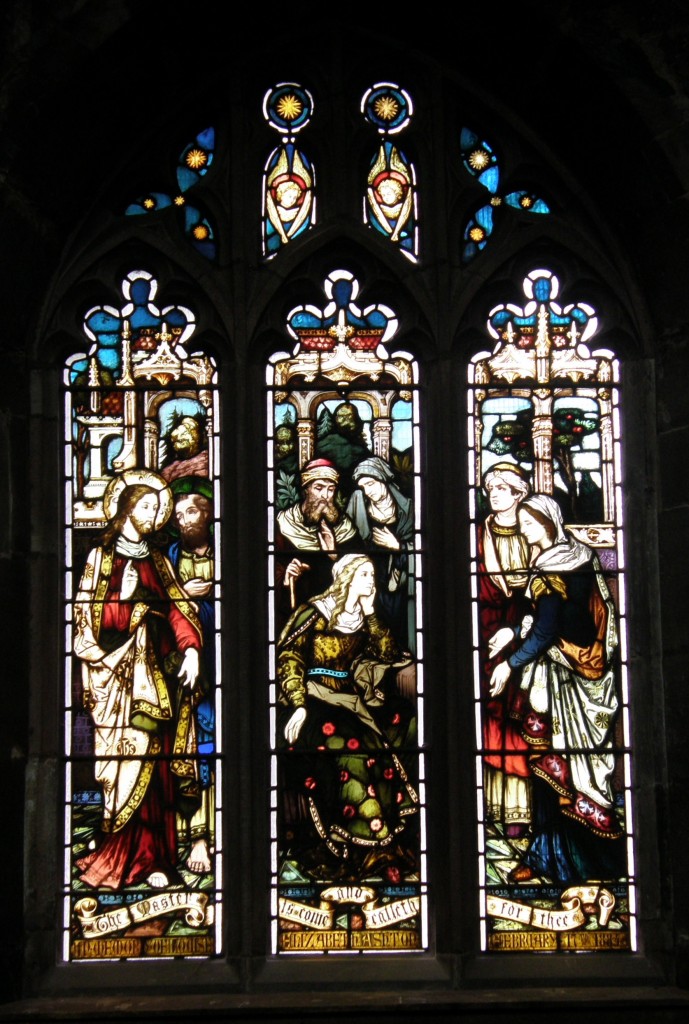

I drove from Wilmslow near Manchester in England to Edinburgh, Scotland, after a very pleasant visit with my friend Sally M. and her husband Tim. Sally and I had gone to the weekday Eucharist at St. Bartholomew’s Church, then toured the Quarry Bank cotton mill historical site maintained by the National Trust. Then I hit the road.

I arrived at the Quality Hotel at the Edinburgh Airport, unloaded my things, cleaned up the interior of the car and made sure I had everything out of it, then drove from the hotel to the rental car return lot … somehow making a wrong turn and ending up in a lane and an area of the airport reserved for “authorized vehicles” only (i.e., buses and taxis). Zipping quickly into an escape lane labeled FastTrack, thinking it was a quick way out of the airport, I found myself headed instead for a £26 short-term parking lot!!! Another quick lane change into a lane labeled Drop Off Only and I was in a covered drive with hundreds of people getting out of cars with their baggage; I finally made it to the exit of this area, only to find I had to pay £1 to open a gate … in any event, I made it to the car park, turned in the car, and went to find the shuttle bus to back to the hotel. On the way, I had the good idea to enter the terminal and locate the Aer Lingus ticket counter which I found at the far left end of the counters. Good, I know where to head in the early morning.

Back out to the shuttle bus and back to the hotel. I’d checked the Aer Lingus web site about baggage limitations and learned that there is 20 kilo limit on luggage, so with two bags that were packed to a 50 lb limit in the states (one about 30 lbs or 16 kilos, one about 48 lbs or 22 kilos) I knew I needed to do some shifting of items and get them more evenly distributed. That took a lot of doing … I spent nearly two hours moving things back and forth and finally getting the one down to 20 kilos (books and my CPAP machine being the heavier and harder to distribute items). Then I hied myself to the bar for a beer and a fish-and-chips dinner.

I went to bed about 11:30 p.m. setting my clock for 5 a.m. so I could get up and get the 6 a.m. shuttle in order to check in the recommended two hours before the 8:20 a.m. flight time. Tossed, turned, last looked at the clock at nearly 1 a.m. and then woke up at 4:00 a.m. and couldn’t go back to sleep. Thirty minutes later I faced the inevitable and got up, showered, finalized the packing, checked out and got to the airport at 6:00 a.m.

Loading my two bags to be checked, my carry-on backpack computer bag, and my jacket on a rolling cart, I headed to the previously scouted Aer Lingus counter … and found that it was now the City-Jet Airlines counter! And, further, that there was no Aer Lingus counter at all! I asked the young woman a the City-Jet counter what was going on. She said their counters are not permanently assigned and changed “all the time.” A young man behind her overheard our conversation and told me that Aer Lingus would open at Counter 14 in a few minutes, so I stood back and waited about 20 minutes and, sure enough, it did open up … with said young man manning the counter. I went up to check in … and he told me my luggage was 17 kilos overweight! All that work to balance the distribution between the bags and now I am told that the 20 kilo limit is “per person” not “per bag”! I would have sworn the website read as if this were a “per bag” limit, but I was reading the “Checked Bags Fees” section and not the “Checked Bags Allowances” section which I have now seen on re-reading the site. So … at £12.00 per kilo overage fee, I pay $330 to send my bags one-way to Ireland – this is $100 dollars more than the round-trip ticket to send me there and back.

Deep sigh of resignation … pay fee, get boarding pass, go off to security and the gates.

Security – guess who gets singled out for special pat-down and carry-on baggage examination.

At this point, I’m about as frustrated with everything as I can be. The Edinburgh Airport has rapidly become a non-favored place in my experience and I am ready to leave. In fact, I’m about ready to say, “This has been a great two-weeks, let’s cancel the rest of this exercise and go home!” But I don’t … I finally get to the gate … and find it’s been changed. So I go to the other gate, fortunately not far away.

Chill for 90 minutes. Go through the check-in procedure, walk out on the tarmac, enter small propeller-driven aircraft, collapse into seat.

Conversation with the woman next to me … she’s from Wichita, Kansas! An emergency physician traveling with her college-age son for a vacation in Scotland and Ireland. Very pleasant 70 minutes on the flight and we arrive at Dublin. Passport, baggage claim, customs, all no problem.

Car rental – pre-arranged months ago for a two-month long-term rental with insurance provided by my VISA card which advertises “world-wide” insurance coverage on rental cars. Except … it turns out … in Ireland, Syria, Iran, and other “terrorist countries” – Ireland? A terrorist country? Really? Long-distance call to the US to the VISA issuer confirms this. Damn! Basic insurance on the car is €15 per day, or €75 per week for a long-term rental. And, oh by the way, we don’t have your reservation … you shouldn’t have been able to do that on the website! Don’t worry, we’ll get it worked out (which they do) but it will have to be another car because we don’t have any in your reserved class with the proper registrations and permits for long-term rental. (I get a bigger car, but at some point, through the Galway office, I’ll have to trad it for the size I reserved.)

Finally, this all gets worked out and I get the car … some sort of Opel sport sedan with a diesel engine. Very posh. Feels HUGE after the little Vauxhall Meriva I’d been driving through the UK. I get my luggage loaded, get my Garmin GPS out of the suitcase, set it up on the dash, turn it on, set my destination, and move out … and get incomprehensible instructions from the GPS! The maps for Ireland are out-of-date. They have built new, high-speed motorways since these maps were produced, and in Dublin they have replaced roundabouts with American-style light-controlled intersections. Garmin’s instructions are worse than useless – they are dangerous! I turn it off and navigate by blind luck, finding my way to the Vodafone store where I am supposed to be able to convert my Nokia cellphone to local service so I don’t have to pay British international roaming charges. Guess what – Vodafone UK misinformed me – Vodafone IE can’t convert the phone. No big deal, I’ll just pay the roaming charges. I can top-up the prepayment arrangement here, so we’ll just go with that.

Back on the road … “Jack” (my Garmin) still is useless – when I’m on the motorway, he thinks I’m driving through farm fields and keeps telling me “Drive to highlighted route.” So he gets turned off again – just follow the signs to Galway. Once I get outside Galway City, Jack is fine – the road in the Gaeltacht don’t change! He guides me properly from Galway City to An Cheathrú Rua.

I arrive at my host family’s home, greet my old friends Feithín and his sister Múirin, children of my hosts, unload the car and collapse for a nap!

These 24 hours have been an exercise in frustration and patience. Thank God, they’re over. Before I take my nap … I open up Dánta Dé and I read this prayer:

Paidir mhilis thrócaire

Atá lán de ghrása

Cuirimid-ne chugad-sa

Dár gcaomhaint ar ár námhaid,

Ag luighe dúinn anocht

Is ag éirghe dúinn amárach,

In onóir na Trionóide

‘S i síthcháin na Páise.

A Íosa mhilis thrócairigh,

A Mhic na h-Óighe cúmhra,

Sábháil sinn ar na piantaibh

‘Tá íochtarach dorcha dúnta.

Leat a ghnímíd á ngearán

Óir is agad ‘tá an tseachrán

Is cuir inn ar an eolas.

In English:

A sweet prayer of mercy,

That is full of graces,

We send to Three,

To protect us from our enemies,

On our lying down tonight,

And on our rising tomorrow:

In honour of the Trinity

And in the peace of the Passion.

O Jesu, sweet, merciful,

O Son of the fragrant Virgin,

Save us from the pains

That are nethermost, dark, emprisoned.

To Thee we make our plaint,

For with Thee is our succor;

Keep us from wandering,

And guide us to [true] wisdom.

Keep us from wandering and guide us to wisdom, indeed! Amen!